Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Skulls Deformed For Fashion

For millennia, humans have altered their body for aesthetic reasons. One of the most ancient and widespread practices was changing the shape of the skull. Technically known as artificial cranial deformation, it involved manipulating babies’ soft skulls.

There were many reasons for modification. Often, it was associated with nobility, beauty, and intelligence. Given the practice’s prevalence, it’s strange that it has become almost unknown in the modern world. Tastes change; it may only be a matter of time before people start deforming their skulls in the name of fashion once more.

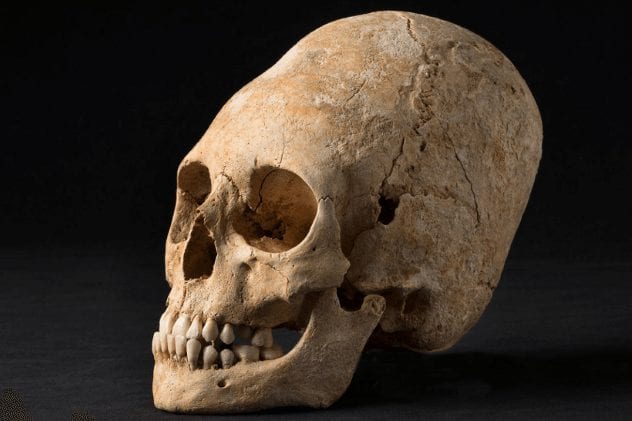

10 The Woman Of Tlailotlacan

In the shadow of Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Sun, archaeologists unearthed a curious skull. It belonged to a woman aged 35 to 40 and was artificially elongated. Her teeth are intriguing. The top front incisors were encrusted in pyrite. A missing lower tooth was replaced by a prosthetic one made of serpentine. This 1,600-year-old skull was an extremely rare find in the area.

Experts believe the “Woman of Tlailotlacan” was a foreign aristocrat. Artificially deformed craniums are common in the Mayan strongholds of Southern Mexico and Central America. However, they are extraordinarily rare in Teotihuacan, located in the center of Mexico. The woman was buried with 19 jars containing offerings, which along with her elongated cranium and extravagant teeth, suggest wealth and nobility.

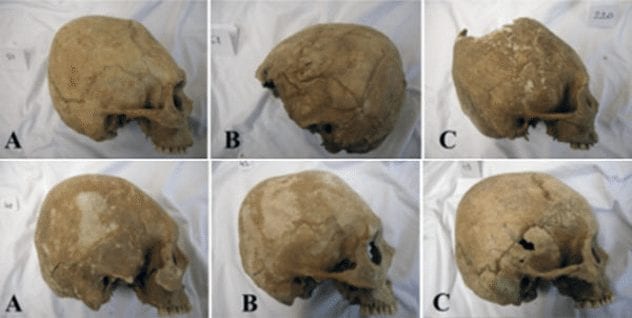

9 Huns Of The Carpathian Basin

Anthropologists discovered nine skulls that reflect artificial cranial deformation in Hungary’s Carpathian Basin. Dated to the fifth and sixth centuries AD, they belonged to the infamous Huns. The skulls show three distinct alteration styles, and both men’s and women’s skulls were modified. Experts have followed a trail of elongated skulls from the Kalmykia Steppe, through Crimea, and on to Europe. This follows the movements of the Huns during the “Migration Period.”

Experts believe that the purpose of the deformation was twofold: a status indicator and a racial identifier. Non-Huns, who hoped to curry favor with the steppe invaders, adopted the practice. We see this trait appearing in many other Germanic tribes: Alan, Sarmatian, Gothic, and Gepidic. The Huns aren’t believed to have originated this technique. Who they learned it from remains a mystery.

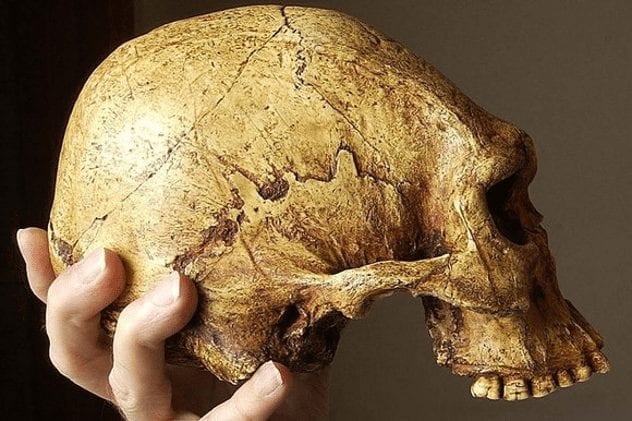

8 Skulls Of Shanidar

Artificial cranial deformation is ancient, going back at least 10,000 years, and recent finds indicate it might be significantly older. At Shanidar Cave in Iraq, archaeologists unearthed two Neanderthal skulls that suggest our ancient cousins might have practiced this as far back as 45,000 years ago. Shanidar 1 and 5 both exhibit evidence of artificial cranial deformation. The most striking aspect of these skulls is their combination of frontal flattening and unnatural curvature at the back. Shanidar 5 shows significant forehead flattening—4.5 standard deviations from the population mean.

It is unlikely that these skulls represent a unique regional variation. Other West Asian specimens exhibit normal skull structures. The most reasonable explanation is that the deformation was created purposefully. This reflects the little-studied aesthetic preference of Neanderthals. Some have linked this practice to the emergence of burying the dead, both of which reflect a pattern of behavior previously associated only with modern humans.

7 Alsatian Noblewoman

During an excavation in Alsace, France, archaeologists uncovered graves and artifacts stretching back 6,000 years. One of the most interesting discoveries was the well-preserved, elongated skull of a woman from 1,600 years ago. Given that she was buried with an array of finery, experts believe she was an aristocrat. Many of her possessions came from the East, leading some to propose that her burial site might have been reserved for warriors from Asia and their families.

Up until the early 20th century, artificial cranial deformation was commonplace in France. The practice of tightly wrapping a baby’s head to avoid accidental impact was referred to locally as bandeau. It resulted in Toulouse deformity. Unlike the modification of the Alsatian noble woman, the Toulouse variety was widespread among the peasantry. Did their tradition trace its origin back to dimly recalled memories of modified nobility?

6 Genocide Skulls

In a remote canyon in New Mexico, archaeologists unearthed evidence of a genocide. They discovered seven skeletons belonging to the Gallina people. This enigmatic culture lived in Northwestern New Mexico between AD 1000 and 1200. All of the seven remains reflect violent trauma. Men, women, and children were brutally murdered. So far, 90 percent of the Gallina remains discovered have met savage ends.

The Gallina skulls show clear evidence of modification. They are flattened at the back of the crown. It is uncertain whether this was done for beautification, cultural identity, or practicality. Either way, this set them apart from their neighbors—and possibly led to them becoming targets. There is evidence that the region experienced a severe drought during this period. It’s likely that the newly arrived Gallina were seen as competition for limited resources—or worse, the cause of the drought.

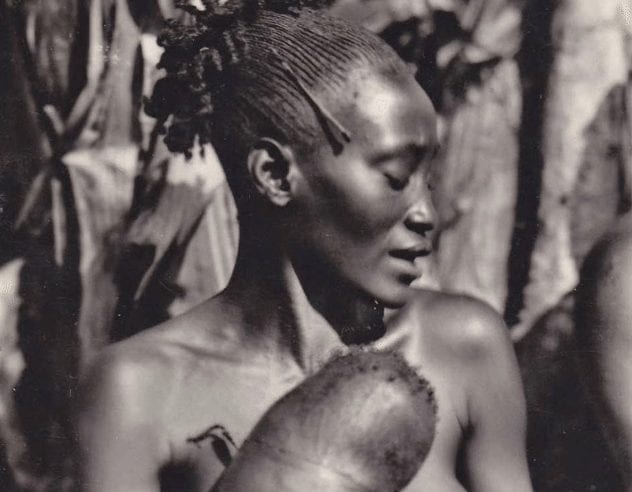

5 Mangbetu

The Mangbetu of Northeastern Congo were known for practicing lipombo—the art of artificially elongating the cranium. Lipombo was a status symbol of the ruling class, who saw deformed skulls as a sign of beauty, power, and intelligence. They wore elaborate, high hairstyles to accentuate the abnormality. The practice is well-documented in photographs. Lipombo continued until 1950, when the Belgian authorities outlawed it.

“Mangbetu” refers not to a population, but a ruling class. In the 19th century, they incorporated neighboring tribes into their territory and borrowed many customs. Lipombo might have been one of these cultural exchanges. The process is started after the child is one month old. A cloth is wrapped around the head to encourage elongation. The process usually doesn’t damage the brain. As long as pressure remains constant, the brain exhibits plastic growth and can expand into whatever space is provided for it. The impact is strictly cosmetic.

4 Sonora Skulls

In 1999, workers in the state of Sonora in Northern Mexico made an unexpected discovery. The unearthed “El Cementerio”—an ancient burial ground containing 13 individuals with artificially elongated craniums. While the site was discovered in 1999, it was only investigated in 2012. The bones date back 1,000 years. In addition, the archaeologists uncovered pendants, nose rings, and other jewelry.

No one is certain why these ancient Sonorans intentionally deformed their skulls. The practice is rarely documented this far north. It has caused experts to reconsider the range of Mesoamerican cultural influence. Additionally, the high number of infants with elongated heads has caused some to speculate that the practice might have been “inept and dangerous.” However, given that cranial deformation occurred throughout the world successfully for millennia, it’s unlikely that this was the cause of their downfall.

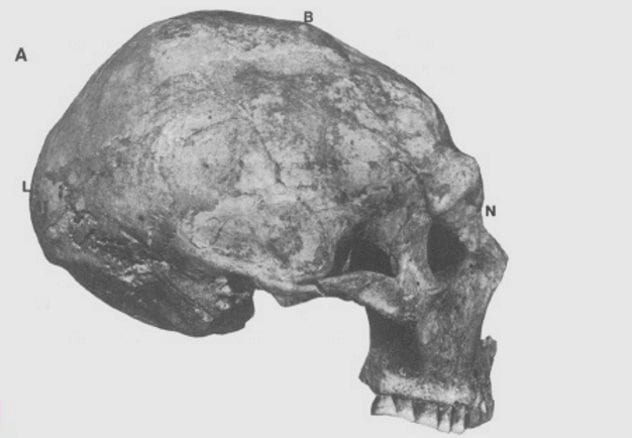

3 The Cohuna Skull

In 1925, a plow unearthed a mysterious skull on the edge of the Australia’s Kow Swamp. It had the ancient features of Homo erectus but was from 10,000 to 30,000 years ago. This combination made it the object of fierce debate and speculation for years. It was a centerpiece of the mutliregional hypothesis, a debunked theory which claimed that Homo sapiens emerged independently in different parts of the world. It was scientific shorthand for racism. Many experts now believe the skull’s low, broad, and elongated forehead is the result of artificial cranial deformation.

The skull is likely to remain the object of mystery for years to come. Many of the features that resemble Homo erectus still cannot be explained by cranial deformation. The teeth and palate are much larger than the average Aboriginal skull. It might be related to a late-living H. erectus population in nearby Indonesia known as Solo Man—or perhaps it’s an unknown hominid waiting to be documented.

2 Paracas Skulls

Four hours south of Lima, Peru, the desert meets the sea at the Paracas Peninsula. In 1928, archaeologists made a discovery here that is still causing debate. The site contained 300 skulls that bore signs of cranial deformation. The practice was commonplace in South America, so what makes these specimens unique? They bear evidence that the people were born with elongated heads.

Cranial deformation does not alter the volume of skulls. However, the Paracas skulls were up to 25 percent larger and 60 percent more massive than average skulls. They only contained one parietal plate, whereas most have two.

Undoubtedly, there is something unusual about these specimens, which has led to wild speculation that these skulls belonged to aliens. A suspicious and misunderstood DNA analysis aided the lunacy. The Paracas specimens had unique maternal signatures. Conspiracy theorists spun this into irrefutable evidence that they were an unknown species—a good story, but extremely unlikely.

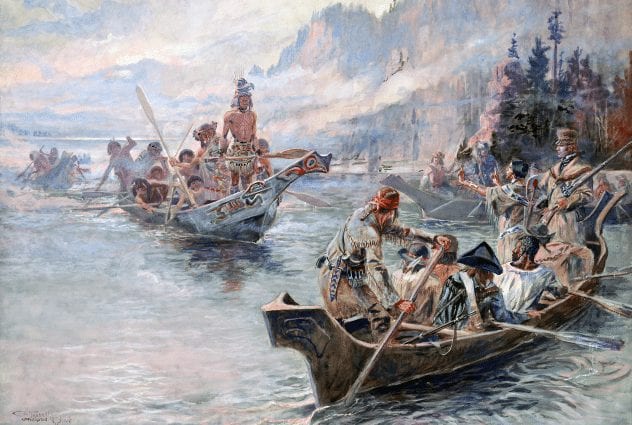

1 Chief Comcomly’s Skull

Artificial cranial deformation was common among the Chinook people of North America’s Pacific Northwest. The process was done through cradle head boarding. Many have noted the similarities between these natives of the Columbia River with those found in South America. In the 19th century, Chinook chief Comcomly was a major power broker in the area, with influence extending far eastward. Comcomly was one of the greeting party for the Lewis and Clark expedition when they reached the Columbia River estuary.

In 1830, Comcomly died in a smallpox outbreak. Four years later, Dr. Meredith Gardner of the Hudson Bay Company robbed the chief’s grave to steal his artificially deformed skull. Gardner dug up the chief, decapitated him, and sent the skull to England. It remained at the Royal Naval Museum for 117 years. The skull eventually made it to the Smithsonian before Comcomly’s relatives insisted they return it. It is now buried on their ancestral land.

Abraham Rinquist is the Executive Director of the Winooski, Vermont, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.