Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Ten Groundbreaking Tattoos with Fascinating Backstories

Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

10 Ancient Psychological Warfare Tactics

Psychological warfare misleads, intimidates, and demoralizes the enemy. This use of threats, propaganda, and subtler strategies has been employed for millennia to influence adversaries’ thinking. Civilians and soldiers alike are targets of this cunning. Those who can control their targets’ emotions and reasoning emerge victorious over superior forces.

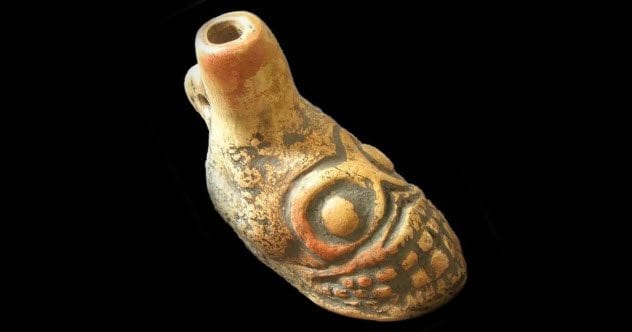

10 Aztec Death Whistles

Aztec death whistles sound like the “scream of 1,000 corpses.” Twenty years ago, archaeologists unearthed two of these skull-shaped instruments in Mexico. They were clutched in the hands of a sacrificed man at the temple of the wind god.

Initially believed to be toys, the whistles were used in rituals and war. Designed to sound like a human howling in pain, death whistles were reserved for rare occasions.

Some insist that death whistles were used in sacrifices and to guide the recently deceased to the land of the dead. Others believe that their main use was psychological warfare.

At the beginning of a battle, the whistles’ unnerving sound would break the resolve of the enemy. Some experts believe that these death whistles allowed listeners to enter a trance state. Aztec physicians frequently employed sound in healing.

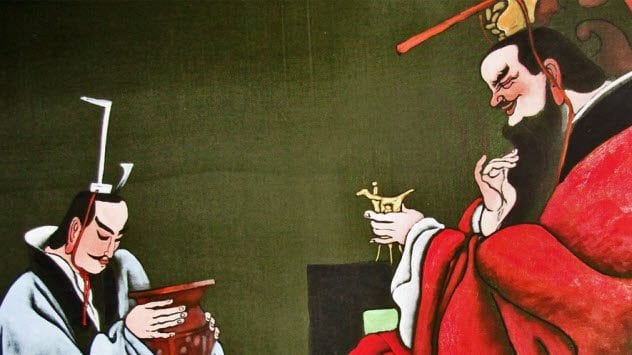

9 36 Stratagems

The 36 Stratagems is an ancient collection of Chinese proverbs on warfare. Most are based on the art of deception and use subtle psychological techniques to undermine an enemy’s will to fight.

The work contains proverbs so universal that they have become cliches. It contains sections on “Attack Strategies,” “Chaos Strategies,” “Desperate Situation Strategies,” and many other scenarios. All modern versions of 36 Stratagems are derived from a ragged copy discovered in Szechwan at a book vendor’s stall in 1941.

The work’s author and publication date remain unknown. Most experts trace the work’s origins to the Warring States Period between 403 and 221 BC. Some of the proverbs refer to specific events as early as 35 BC. In addition, most experts now believe that there was no single author and that 36 Stratagems was compiled over centuries.

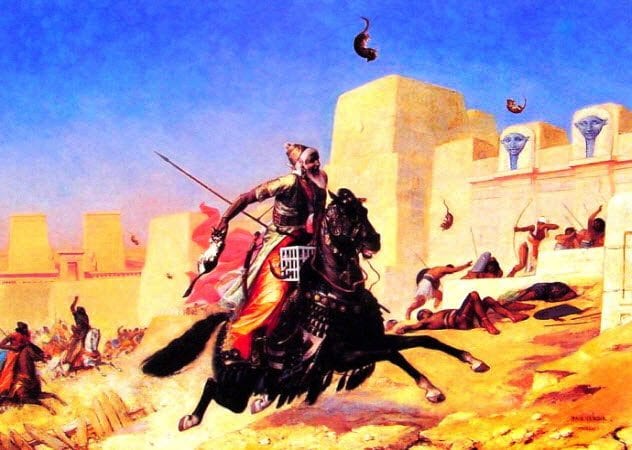

8 Sacred Shields

In 525 BC, the Battle of Pelusium marked Egypt’s decisive defeat by the Persians and a milestone of psychological warfare. Led by Emperor Cambyses II, the Achaemenid Persians swept in from the east and exploited the Egyptians’ reverence for felines.

The invaders drew cats on their shields. Some speculate that they may have pinned real cats to their protective gear. The Egyptians worshiped the feline god Bastet and refused to harm their sacred symbol. In Stratagems, Polyaenus insists that the Persian front line contained dogs, ibises, sheep, and cats—all sacred to the Egyptians.

According to Herodotus, Cambyses invaded because he had been tricked by the pharaoh. Cambyses had requested the hand of Amasis’s daughter in marriage. Assuming she would become a concubine, the Egyptian ruler disguised the daughter of the former pharaoh in her place.

When Cambyses discovered the charade, he attacked. Polyaenus believed that Cambyses’s victory was due to psychological warfare.

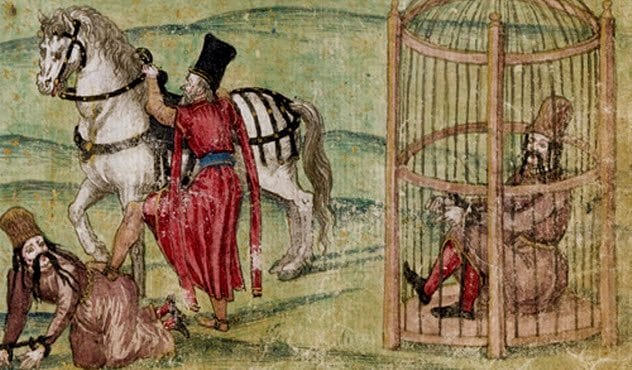

7 Terror Tactics Of Tamerlane

Born in 1336, Timur the Lame (aka Tamerlane) was a 14th-century Uzbek chieftain. Despite the paralysis of half his body, he conquered Central Asia, most of the Muslim world, and parts of India.

Legends of Tamerlane’s terror tactics are legion. Historians estimate that his forces slaughtered 17 million people—5 percent of the world at the time. He became infamous for building pyramids with the skulls of his vanquished. The technique was intended to spread fear in anyone who dared to oppose him.

Some say that he beheaded 90,000 residents of Baghdad and built 120 pyramids with their skulls. After he defeated Delhi, Tamerlane slaughtered the city as a lesson to India. It took nearly a century for Delhi to recover from the devastation.

After defeating the Ottoman Empire, Tamerlane took the Byzantine gates home with him. He also took the sultan in a cage, which he kept on display in his parlor.

6 Vlad The Impaler

Vlad III (aka Vlad Dracula or Vlad the Impaler) was one of the most adept students of psychological warfare in history. The 15th-century Romanian prince spent much of his youth as a political hostage of the Ottomans.

Although he was treated well, Vlad developed a bilious hatred of his captors. Some speculate that the Ottomans even taught him his favorite method of psychological warfare: impaling.

In 1462, Sultan Mehmet II invaded Vlad’s territory. Upon entering the capital, the sultan was greeted by what looked like a forest of Ottoman POWs’ festering corpses impaled on spikes.

Nearly all records of Vlad were written by his enemies. While far from factual, they provide insight into the fear he inspired. Vlad was forced to find ingenious means of fighting with limited resources. Psychological warfare offered the solution. It might seem cruel, but it was an effective tactic against a force much larger than his own.

5 Philip II Of Macedonia

Philip II of Macedonia laid the groundwork for the “greatness” of his son, Alexander. When Philip took the throne in 359 BC, Macedonia was a fractured backwater subject to the whims of foreigners. In less than a year, Philip quashed all internal threats and set up Macedonia to become an ancient superpower. He was a master of psychological warfare.

When doing battle with the Chalcidian League, Philip destroyed the city of Stagirus. According to ancient accounts, it would have been hard for a visitor to tell that the city had ever been inhabited. The remaining Chalcidian cities surrendered without resistance.

During the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Philip employed two strategies of psychological warfare. First, he tired out the Athenian and Theban rebels through boredom, forcing them to wait in the blistering sun. Then he made a false attack, which drew them toward a slowly retreating front line that ensnared them.

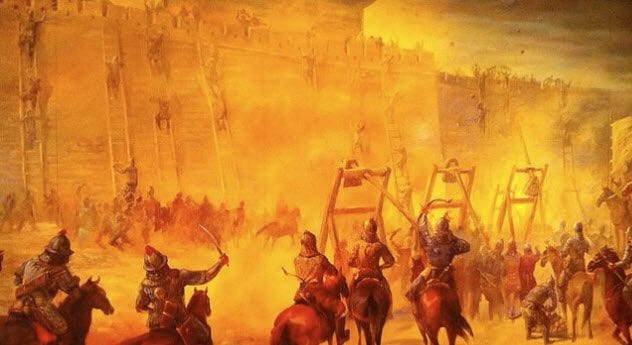

4 Genius Of Genghis Khan

Terror was Genghis Khan’s greatest tool. He destroyed cities that opposed him—slaying soldiers and civilians alike. During the siege of Merv, each Mongol soldier was ordered to decapitate 400 inhabitants before burning the city to the ground. The death toll may have been inflated tenfold, but Genghis wanted it that way.

Genghis often exaggerated the size of his forces. He placed dummies on horseback and had each soldier light a string of bonfires at night. When attacking both Samarkand and Europe, he advanced on fronts over 1,300 kilometers (800 mi), preventing the enemy from knowing his numbers.

Genghis’s feigned retreats lured pursuers into a prepared position where archers annihilated them. Without fail, Genghis knew more about his adversaries than his enemies knew of the Mongols. Genghis exploited this lack of information to create division and fear. He also terrified opponents with camel-mounted kettledrums thundering with Mongol cavalry charges.

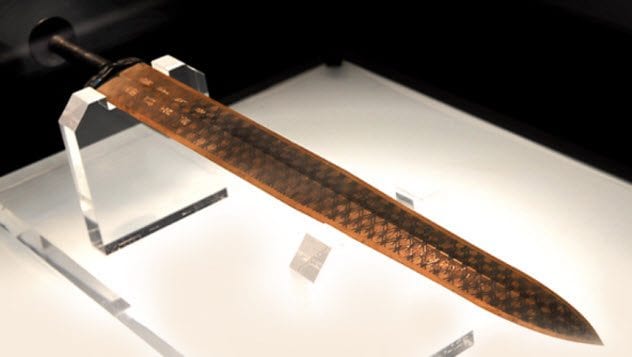

3 Suicide Army

King Goujian of Yue reigned between 496 and 465 BC, the latter part of the Spring and Autumn Period that was marked by a conflict with the state of Wu. During this battle, Goujian had his front line decapitate themselves as a bizarre form of psychological warfare.

According to a history of ancient China called the Shiji, Goujian’s suicidal front was composed of condemned criminals. However, some believe that “criminals sentenced to death” should be read as “soldiers willing to die.” This reflects an ancient Chinese worldview that one would be compensated for sacrifices made during life.

Decapitation might be better translated as “committing suicide by cutting your throat.” This was a common technique in ancient China. However, others believe that the self-decapitating soldiers are nothing more than a legend.

Either way, after years of struggle, Goujian overcame his adversary and annexed their territory.

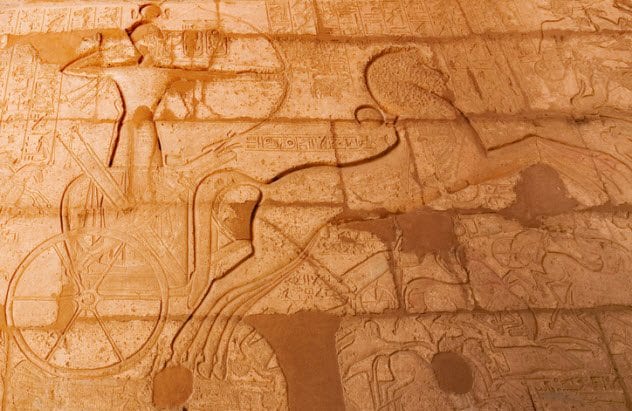

2 War Chariots

During the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC, Hittite forces used heavy chariots to crash through the lines of Ramses II’s Re division (aka Army of Re), causing chaos and terror.

In contrast, the lighter Egyptian war chariots were manned by a driver and a fighter, usually with a bow and arrow and occasionally a spear. They could maneuver more quickly than their enemies in heavier chariots, which could allow the Egyptians to dispatch their enemies before the enemies returned to their own side.

Most experts believe that the invading Hyksos introduced the chariot to Egypt in the Second Intermediate Period. By the 15th century BC, Thutmose III had over 1,000 chariots at his command. These were used against infantry and had an enormous psychological impact on untrained and inexperienced soldiers. By 1000 BC, mounted cavalry replaced the war chariot.

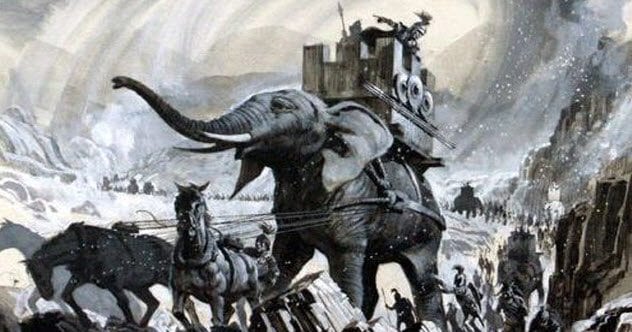

1 Hannibal’s Folly

Carthaginian General Hannibal Barca drove the Romans mad with his psychological warfare techniques in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC). During the Battle of Trebia in 218 BC, Hannibal lured the Roman forces across the Trebia River with an attack of Numidian horsemen.

Hannibal lay in ambush on the other side and slaughtered the Romans, who emerged disorganized, tired, and freezing. At the Battle of Lake Trasimene the following year, he goaded Flaminus into battle by exploiting the Roman general’s headstrong nature.

Hannibal’s name is almost synonymous with his march over the Alps with war elephants. Curiously, this bold attempt at psychological warfare was actually a blunder. Elephants were not adapted to the cold environment. Those that survived the trek were weak and ineffective.

Abraham Rinquist is the executive director of the Winooski, Vermont, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.