History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Greatest Native American Chiefs And Leaders

If you live in the the United States (and even if you don’t) you’ve probably heard about a number of the country’s prominent historical figures. But what about the history of those who were there before? Even many Americans know very little of Native American history.

One of many overlooked aspects of Native American history is the long list of exceptional men who led various tribes as chiefs or war leaders. Just as noble and brave as anyone on the Mexican, British, or American sides, many of them have been swept into the dustbin of history. Here are ten of the greatest Native American chiefs and leaders.

10 Victorio

A member of the Apache tribe, Victorio was also the chief of his particular band, the Chiricahua. He was born in what is now New Mexico in 1809, when the land was still under Mexican control.[1] For decades, the United States had been taking Native American lands, and Victorio grew up in turbulent times for his people. Because of that experience, he became a fearsome warrior and leader, commanding a relatively small band of fighters on innumerable raids.

For more than ten years, Victorio and his men managed to evade the pursuing US forces before he finally surrendered in 1869. Unfortunately, the land he accepted as the spot for their reservation was basically inhospitable and unsuitable for farming. (It’s known as Hell’s Forty Acres.) He quickly decided to move his people and became an outlaw once again. In 1880, in the Tres Castillos Mountains of Mexico, Victorio was finally surrounded and killed by Mexican troops. (Some sources, especially Apache sources, say he actually took his own life.)

Perhaps more interesting than Victorio was his younger sister, Lozen. She was said to have participated in a special Apache puberty rite which was purported to have given her the ability to sense her enemies. Her hands would tingle when she was facing the direction of her foes, with the strength of the feeling telling how close they were.

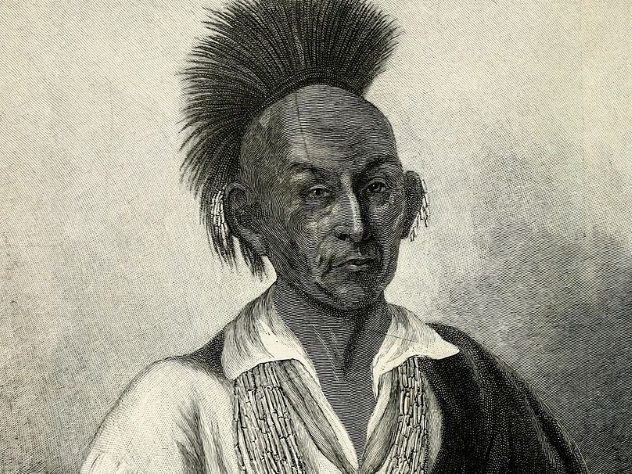

9 Chief Cornstalk

More popularly known by the English translation of his Shawnee name Hokolesqua, Chief Cornstalk was born sometime around 1720, probably in Pennsylvania.[2] Like much of the Shawnee people, he resettled to Ohio in the 1730s as a result of continuous conflict with invading white settlers (especially over the alcohol they brought with them). Tradition holds that Cornstalk got his first taste of battle during the French and Indian War, in which his tribe sided with the French.

A lesser-known conflict called Lord Dunmore’s War took place in 1774, and Cornstalk was thrust into fighting once again. However, the colonists quickly routed the Shawnee and their allies, compelling the Native Americans to sign a treaty, ceding all land east and south of the Ohio River. Though Cornstalk would abide by the agreement until his death, many other Shawnee bristled at the idea of losing their territory and plotted to attack once again. In 1777, Cornstalk went to an American fort to warn them of an impending siege. However, he was taken prisoner and later murdered by vengeance-seeking colonists.

Cornstalk’s longest-lasting legacy has nothing to do with his actions in life. After his death, when reports of a flying creature later dubbed the “Mothman” began to surface in West Virginia, its appearance was purported to have come about because of a supposed curse which Cornstalk had laid on the land after the treachery that resulted in his death.

8 Black Hawk

A member and eventual war leader of the Sauk tribe, Black Hawk was born in Virginia in 1767. Relatively little is known about him until he joined the British side during the War of 1812, leading to some to refer to Black Hawk and his followers as the “British Band.” (He was also a subordinate of Tecumseh, another Native American leader on this list.) A rival Sauk leader signed a treaty with the United States, perhaps because he was tricked, which ceded much of their land, and Black Hawk refused to honor the document, leading to decades of conflict between the two parties.

In 1832, after having been forcibly resettled two years earlier, Black Hawk led between 1,000 and 1,500 Native Americans back to a disputed area in Illinois.[3] That move instigated the Black Hawk War, which only lasted 15 weeks, after which around two-thirds of the Sauk who came to Illinois had perished. Black Hawk himself avoided capture until 1833, though he was released in a relatively short amount of time. Disgraced among his people, he lived out the last five years of his life in Iowa. A few years before his death, he dictated his autobiography to an interpreter and became somewhat of a celebrity to the US public.

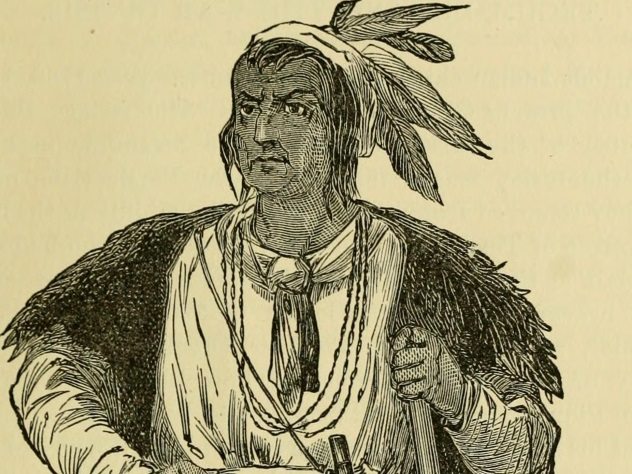

7 Tecumseh

Another Shawnee war leader, Tecumseh was born in the Ohio Valley sometime around 1768. Around the age of 20, he began going on raids with an older brother, traveling to various frontier towns in Kentucky and Tennessee. After a number of Native American defeats, he left to Indiana, raising a band of young warriors and becoming a respected war chief. One of his younger brothers underwent a series of visions and became a religious prophet, going so far as to accurately predict a solar eclipse.

Using his brother’s abilities to his advantage, Tecumseh quickly began to unify a number of different peoples into a settlement known as Prophetstown, better known in the United States as Tippecanoe.[4] One day, while Tecumseh was away on a recruiting trip, future US president William Henry Harrison launched a surprise attack and burned it to the ground, killing nearly everyone.

Still angered at his people’s treatment at the hands of the US, Tecumseh joined forces with Great Britain when the War of 1812 began. However, he died at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813. Though he was a constant enemy to them, Americans quickly turned Tecumseh into a folk hero, valuing his impressive oratory skills and the bravery of his spirit.

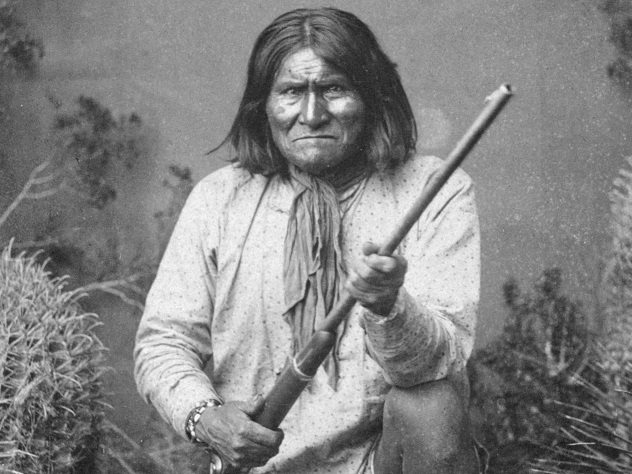

6 Geronimo

Perhaps the most famous Native American leader of all time, Geronimo was a medicine man in the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua. Born in June 1829, he was quickly acclimated to the Apache way of life. As a young boy, he swallowed the heart of his first successful hunting kill and had already led four separate raids before he turned 18.[5] Like many of his people, he suffered greatly at the hands of the “civilized” people around him. The Mexicans, who still controlled the land, killed his wife and three young children. (Though he hated Americans, he maintained a deep-seated abhorrence for Mexicans until his dying day.)

In 1848, Mexico ceded control of vast swaths of land, including Apache territory, in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This preceded near-constant conflict between the new American settlers and the tribes which lived on the land. Eventually, Geronimo and his people were moved off their ancestors’ land and placed in a reservation in a barren part of Arizona, something the great leader deeply resented. Over the course of the next ten years, he led a number of successful breakouts, hounded persistently by the US Army. In addition, he became a celebrity for his daring escapes, playing on the public’s love of the Wild West.

He finally surrendered for the last time on September 4, 1886, followed by a number of different imprisonments. Shortly before his death, Geronimo pleaded his case before President Theodore Roosevelt, failing to convince the American leader to allow his people to return home. He took his last breath in 1909, following an accident on his horse. On his deathbed, he was said to have stated: “I should never have surrendered; I should have fought until I was the last man alive.”

5 Crazy Horse

A fearsome warrior and leader of the Oglala Sioux, Crazy Horse was born around 1840 in present-day South Dakota.[6] One story about his name says that he was given it by his father after displaying his skills as a fighter. Tensions between Americans and the Sioux had been increasing since his birth, but they boiled over when he was a young teenager. In August 1854, a Sioux chief named Conquering Bear was killed by a white soldier. In retaliation, the Sioux killed the lieutenant in command along with all 30 of his men in what is now known as the Grattan Massacre.

Utilizing his knowledge as a guerilla fighter, Crazy Horse was a thorn in the side of the US Army, which would stop at nothing to force his people onto reservations. The most memorable battle in which Crazy Horse participated was the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the fight in which Custer and his men were defeated. However, by the next year, Crazy Horse had surrendered. The scorched-earth policy of the US Army had proven to be too much for his people to bear. While in captivity, he was stabbed to death with a bayonet, allegedly planning to escape.

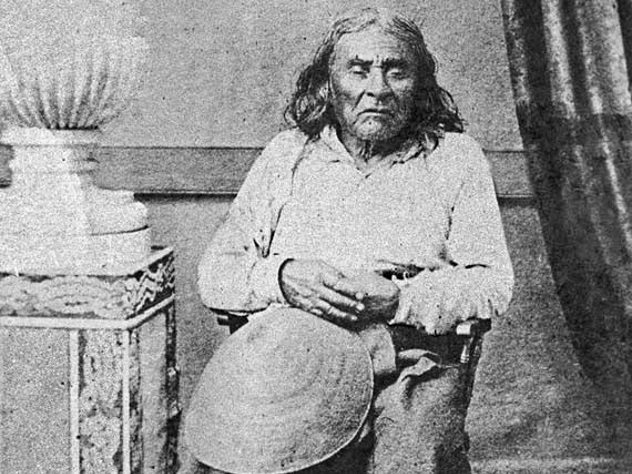

4 Chief Seattle

Born in 1790, Chief Seattle lived in present-day Washington state, taking up residence along the Puget Sound. A chief of two different tribes thanks to his parents, he was initially quite welcoming to the settlers who began to arrive in the 1850s, as were they to him. In fact, they established a colony on Elliot Bay and named it after the great chief. However, some of the other local tribes resented the encroachment of the Americans, and violent conflicts began to rise up from time to time, resulting in an attack on the small settlement of Seattle.[7]

Chief Seattle felt his people would eventually be driven out of every place by these new settlers but argued that violence would only speed up the process, a sentiment which seemed to cool tempers. The close, and peaceful, contact which followed led him to convert to Christianity, becoming a devout follower for the rest of his days. In a nod to the chief’s traditional religion, the people of Seattle paid a small tax to use his name for the city. (Seattle’s people believed the mention of a deceased person’s name kept him from resting peacefully.)

Fun fact: The speech most people associate with Chief Seattle, in which he puts a heavy emphasis on mankind’s need to care for the environment, is completely fabricated. It was written by a man named Dr. Henry A. Smith in 1887.

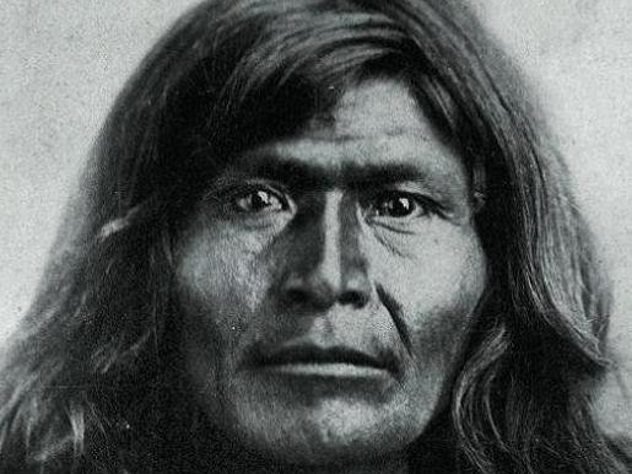

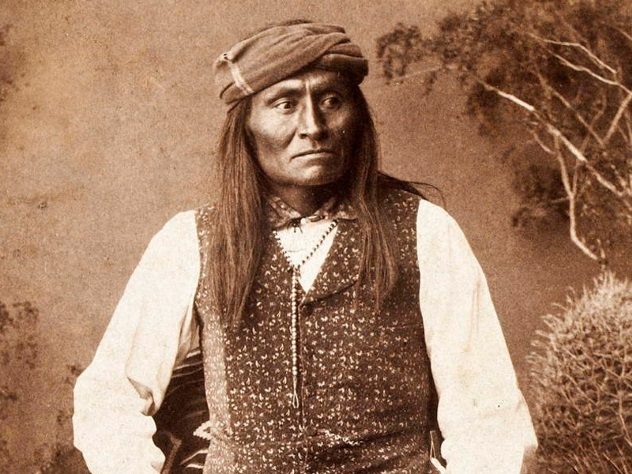

3 Cochise

Almost nothing is known about the childhood of one of the greatest Apache chiefs in history. In fact, no one is even sure when he was born. Relatively tall for his day, he was said to have stood at least 183 centimeters (6′), cutting a very imposing figure. A leader of the Chiricahua tribe, Cochise led his people on a number of raids, sometimes against Mexicans and sometimes against Americans. However, it was his attacks on the US which led to his demise.

In 1861, a raiding party of a different Apache tribe kidnapped a child, and Cochise’s tribe was accused of the act by a relatively inexperienced US Army officer.[8] Though they were innocent, an attempt at arresting the Native Americans, who had come to talk, ended in violence, with one shot to death and Cochise escaping the meeting tent by cutting a hole in the side and fleeing. Various acts of torture and execution by both sides followed, and it seemed to have no end. But the US Civil War had begun, and Arizona was left to the Apache.

Less than a year later, however, the Army was back, armed with howitzers, and they began to destroy the tribes still fighting. For nearly ten years, Cochise and a small band of fighters hid among the mountains, raiding when necessary and evading capture. In the end, Cochise was offered a huge part of Arizona as a reservation. His reply: “The white man and the Indian are to drink of the same water, eat of the same bread, and be at peace.” Unfortunately for Cochise, he didn’t get to experience the fruits of his labor for long, as he became seriously ill and died in 1874.

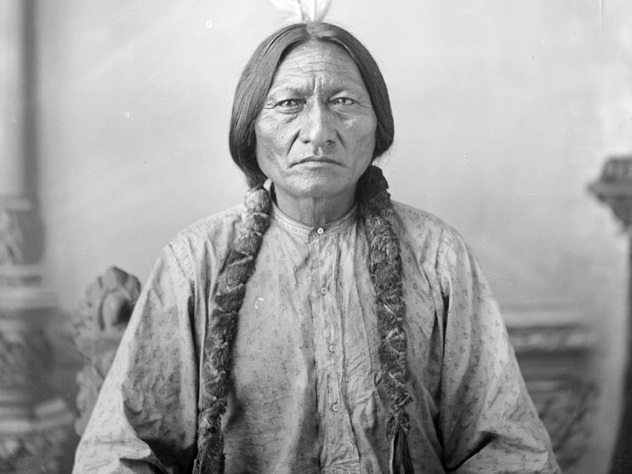

2 Sitting Bull

A chief and holy man of the Hunkpapa Lakota, Sitting Bull was born in 1831, somewhere in present-day South Dakota.[9] In his youth, he was an ardent warrior, going on his first raid at only 14. His first violent encounter with US troops was in 1863. It was this bravery which led to him becoming the head of all the Lakota in 1868. Though small conflicts between the Lakota and the US would continue for the decade, it wasn’t until 1874 that full-scale war began. The reason: Gold had been found in the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota. (The land had been off-limits thanks to an earlier treaty, but the US discarded it when attempts to buy the land were unsuccessful.)

The violence culminated in a Native American coalition facing off against US troops led by Custer at the aforementioned Battle of the Little Bighorn. Afterward, many more troops came pouring into the area, and chief after chief was forced to surrender, with Sitting Bull escaping to Canada. His people’s starvation eventually led to an agreement with the US, whereupon they were moved to a reservation. After fears were raised that Sitting Bull would join in a religious movement known as the Ghost Dance, a ceremony which purported to rid the land of white people, his arrest was ordered. A gunfight between police and his supporters soon erupted, and Sitting Bull was shot in the head and killed.

1 Mangas Coloradas

The father-in-law to Cochise and one of the most influential chiefs of the 1800s, Mangas Coloradas was a member of the Apache. Born just before the turn of the century, he was said to be unusually tall and became the leader of his band in 1837, after his predecessor and many of their band were killed. They died because Mexico was offering money for Native American scalps—no questions asked. Determined to not let that go unpunished, Mangas Coloradas and his warriors began wreaking havoc, even killing all the citizens of the town of Santa Rita.

When the US declared war on Mexico, Mangas Coloradas saw them as his people’s saviors, signing a treaty with the Americans allowing soldiers passage through Apache lands.[10] However, as was usually the case, when gold and silver were found in the area, the treaty was discarded. By 1863, the US was flying a flag of truce, allegedly trying to come to a peace agreement with the great chief. However, he was betrayed, killed under the false pretense that he was trying to escape, and then mutilated after death. Asa Daklugie, a nephew of Geronimo, later said this was the last straw for the Apache, who would began mutilating those who had the bad luck to fall into their hands.

Read more on the (unfortunately dark) history of Native Americans on 10 Horrific Native American Massacres and 10 Atrocities Committed Against Native Americans In Recent History.