History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

Ten Books Burned by the Nazis

As far as free speech goes, May 10, 1933, was one of Western Civilization’s saddest, most frightening days. That’s the date the newly-empowered Nazi Party led a wholesale literary immolation—participated in by university students and broadcast on radio stations throughout Germany—at Bebelplatz, the square of the Berlin Opera House. Some 25,000 volumes of books deemed “un-German” were incinerated in an eerie, foreshadowing attempt to extinguish the authors and ideas they represented.[1]

Books about communism or pacifism, literature seen as questioning German culture or racial superiority, and material deemed sexually explicit went up in smoke—as did, of course, anything written by Jews or anti-Hitler dissidents. As evidenced by these ten tomes, the Nazis practiced cancel culture well before the advent of Twitter.

Related: 10 Songs That Were Once Surprisingly Banned

10 All Quiet on the Western Front (Erich Remarque)

Or should we say “Im Westen Nichts Neues”? That’s German for “In the West, Nothing New”—and it’s the original title of the novel authored by German World War I veteran Erich Maria Remarque.

The 1929 instant classic, whose 1930 American cinema adaptation became the first movie based on a novel to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, helped make the translated phrase synonymous with stagnancy. It also pissed off Adolf Hitler something fierce.

Unsurprisingly, Hitler, who served as a Lance Corporal in the Kaiser’s army during the Great War, wasn’t too keen on dwelling upon Germany’s embarrassing defeat unless it served his revenge narrative of the perceived grave injustices the 1918 Armistice foisted upon his homeland. In fact, when he conquered France in 1940, Hitler held the formal surrender ceremony in the same rail carriage where Germans surrendered to Allied forces 22 years earlier.[2]

Far from romanticizing the German soldier, Remarque shined a spotlight on the inhumane physical and mental conditions under which German soldiers toiled in the Great War’s trenches, as well as the detachment from society many soldiers felt upon returning to civilian life. As much as anything, All Quiet broke ground, not for its depiction of armed conflict—war is hell, everyone knows that—but the weird normalcy of post-conflict life. As a result, it’s one of the earliest in-depth portrayals of what we’d recognize today as military-specific post-traumatic stress disorder.

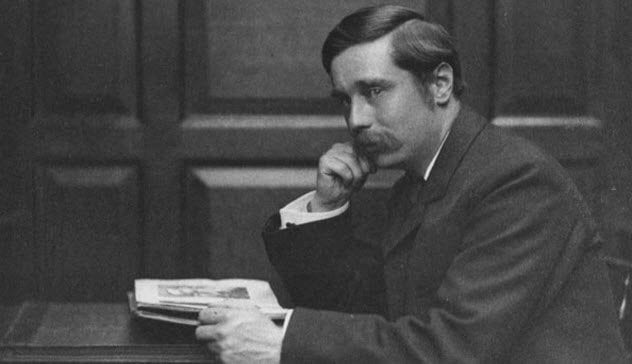

9 The Outline of History (H.G. Wells)

How did a 19th Century science-fiction specialist end up in Hitler’s book bonfire? Because one of his nonfiction books challenged a key tenet of Nazi orthodoxy.

While classics like The Time Machine (1895), War of the Worlds (1897), and The Invisible Man (also 1897) were Wells’s most memorable works, his most ambitious effort came over two decades later. In 1919, he began a softcover series titled The Outline of History. Boldly subtitled The Whole Story of Man, the project totaled more than 1,300 pages spanning the beginning of time (Chapter 1: “The Origins of Earth” to then-present day (Chapter 39: “The Great War”).

Wells’s inspiration was simple: he found the quality of history textbooks lacking and figured he could do better. Notably, he attempted to weave the human narrative into common themes. Among other motifs, Wells saw human history as a quest for a common purpose—one punctuated in cycles when nomads conquered settled civilizations. From there, he elaborates on the advancement of “free intelligence,” as figures like ancient Greek historian Herodotus exemplified “a new step forward in the power and range of the human mind.”

But it was Wells’s egalitarian views on race that earmarked The Outline of History for fire fodder. Wells firmly rejects any theories of racial or even civilizational superiority, writing that man “is an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture,” and that any honest assessment of Western minds’ supposed superiority “dissolves into thin air.” [3]

8 The Metamorphosis (Franz Kafka)

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into an enormous insect.”

Fueled by one of the most memorable opening lines in literary history, The Metamorphosis is a novella-length allegory whose potential interpretations include the alienating demands of modern society, the incompatibility of individualism and structure, and the largely transactional nature of relationships.

The Nazis weren’t fans of any of these motifs, per their attempts to instill a selfless commitment to Germany—one buttressed by the concept of racial superiority (i.e., “We can struggle and sacrifice for the Fatherland because we’re better than everyone else.”). The Metamorphosis was many things—but it certainly wasn’t a call to collective duty in an idyllic society.

Oh, and it was written by a Jew. Hitler tended to frown upon that.

As Gregor’s family realizes the change is permanent, they hole him up in a room, remove his cherished belongings, and increasingly ostracize him. His sister, Grete, is the only one willing to feed him, and slowly, even her loyalty and sympathy wane.

Eventually, Grete goes from her six-legged brother’s only defender to chief detractor, urging his ouster and prompting him to intentionally starve himself to death. In fact, many have argued the most radical metamorphosis is Grete’s, as the ordeal transformed her from kind and selfless to cold and practical—just like society wants her. She would have made a good Nazi.[4]

7 Heart of Darkness (Joseph Conrad)

The late 19th Century saw the Scramble for Africa, a mad dash by European powers to claim and colonize territory across Africa, the so-called Dark Continent. At the height of this extortionist folly, which lasted roughly until World War I, Polish-English writer Joseph Conrad penned an eerie, slow-building novel about a journey into the Congo Free State.

Published in 1899, Heart of Darkness tells the tale of Charles Marlow, a ferry captain tasked by a Belgian trading company with leading an expedition into deepest, darkest Africa. The further he goes, the freakier it gets. Early on, he comes across a railroad construction whose African laborers now lay dying, the epitome of exploitation.

Marlow is informed of the mysterious Mr. Kurtz and treks 200 miles to Central Station, where his riverboat awaits. Only it doesn’t; it’s been wrecked, and the repairs take months, during which time his ominous intrigue over Kurtz grows. Finally, the crew embarks on a two-month journey downriver but are attacked by natives just before reaching Kurtz’s Inner Station.

It turns out the natives were defending Kurtz, who they’d come to worship as something approaching a god, despite—or perhaps due to—his practice of severing their heads and mounting them on posts. The dripping-wet symbolism was a thinly veiled critique of Europe’s racist raping of Africa and its peoples. It’s little wonder why Hitler objected to such narratives on the moral failings of conquest, colonization, and homicidal hubris. [5]

6 “How I Became a Socialist” (Helen Keller Essay)

The Nazis didn’t just burn books. Their literary bonfires included newspapers printing opinions contrary to Nazi doctrine. One such paper was the now-defunct New York Call, which on November 2, 1912, ran an essay by Helen Keller, who rose to inspirational influence despite being stricken deaf and blind as an infant.

By 1912, Keller had already been prominent for nearly a decade, having published her remarkable memoir, The Story of My Life, while still a student at Radcliffe College. The book detailed her against-all-odds rise from a near-total inability to communicate to what the tome showcases: an exceptionally eloquent writer. The following year, she became the first deaf-blind person to graduate from Radcliffe.

As she matured into adulthood, Keller became an active suffragist, pacifist, and champion of worker’s rights. Her 1912 New York Call column attempts to explain her passions for these socialist positions.

Keller’s writings may have been spared the pyre, though, had it not been for another essay published 21 years later. On May 9, 1933—the eve of the scheduled mass book burning—Keller published an open letter to German students in The New York Times. “History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas,” Keller writes. “Tyrants have tried to do that often before, and the ideas have risen up in their might and destroyed them.”[6]

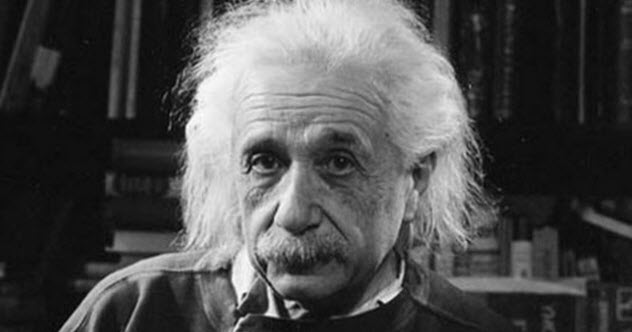

5 Cosmic Religion (Albert Einstein)

In late 1930, one of Germany’s greatest minds was asked about the emerging Nazi Party, which had recently won over 18% of the vote in parliamentary elections—the second most of any group.

“I do not enjoy Herr Hitler’s acquaintance,” the man who would become synonymous with genius said. “As soon as economic conditions improve, he will no longer be important.” He also took a conservative approach to the party’s fervent anti-Semitism. “Solidarity of the Jews, I believe, is always called for, but any special reaction to the election results would be quite inappropriate.”

Hell, even Albert Einstein gets it wrong sometimes.

Hitler’s beef with Einstein extended further than his Jewish heritage; had Einstein stayed strictly academic, it’s doubtful that tomes on his 1915 Theory of Relativity would have ignited enough passion to be…well, ignited. However, Einstein was an outspoken pacifist dating back to 1914, when he balked at signing a document endorsed by scores of German intellectuals justifying Germany’s militarism leading up to World War 1.

Einstein’s views on religion were, perhaps, even more threatening to Nazi propaganda. In a 1931 work titled Cosmic Religion, Einstein reveals that science, not conventional religions, form the basis of his spirituality. In doing so, he rejects the idea of an interventionist deity—a big Nazi no-no, since Hitler believed his Third Reich was preordained for domination.[7]

Luckily, Hitler’s 1933 rise to power came while Einstein was visiting the United States. So he stayed. Your loss, Adolf.

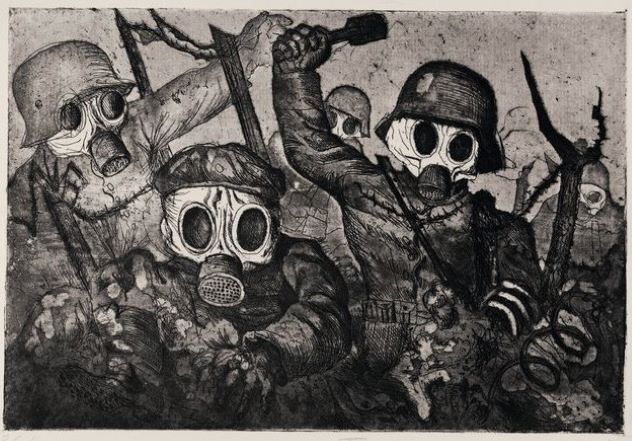

4 Unnamed Artwork Compilations (Otto Dix)

It’s well documented that Hitler was an art enthusiast, if not an aficionado. As his armies overwhelmed and occupied one European country after another, Hitler had his pick from some of the world’s finest museums, pillaging his way to a massive art collection.

Not surprisingly, though, if art didn’t meet Hitler’s perceptions, it hung in effigy rather than over his mantel. As a result, many of the books burned at Bebelplatz were printed collections of influential artists (think coffee table books) Hitler deemed illicit, overly decadent, or anathema to German pride.

One such artist was Otto Dix, a German painter and printmaker who gained prominence for his brutally honest depictions of war and society during Germany’s post-Great War Weimar Republic. A strong example of the former is his 1932 panel painting The War, whose horrific images include a devastated urban landscape strewn with war paraphernalia and body parts. Luckily, the original painting survived the war; the May 10 burnings were largely limited to printed depictions rather than actual paintings.

Hitler, however, wasn’t done with Dix: In 1933, the Nazis forced him from his teaching position at the Dresden Academy and, four years later, featured his work in a special exhibition in Munich called “Degenerates,” intended to show the German public what art should NOT be in the Third Reich. Still, Dix refused to flee Germany and, eventually, was forced into the Nazi army at the ripe old age of 53.[8]

3 A Brave New World (Aldous Huxley)

Dude…don’t mess with Henry Ford. That’s Hitler’s boy.

Six years before accepting the Grand Cross of the German Eagle—the highest honor bestowed on foreigners by the Nazi Party—Henry Ford was immortalized, of sorts, in English author Aldous Huxley’s dystopian work about an environmentally engineered society (pictured above). So revered by Huxley’s futuristic World State is the famously anti-Semitic automobile tycoon that the novel is set in the year AF—After Ford—632 (that’s 2540AD to you and me). In fact, “Ford” is substituted for “Lord” by the populace, a sort of pre-Twitter troll on Huxley’s part.

Even without its mockery of der Fuhrer’s favorite American, Huxley’s 1932 masterpiece was bonfire-bound from the get-go. Amounting to a flashing red literary warning against the dangers of groupthink and unchecked authority, A Brave New World features several technological innovations Hitler undoubtedly would have coveted. From genetic engineering in artificial wombs and childhood indoctrination through a Calvinist caste system to happiness-producing drugs to keep the populace pleasantly compliant, the work is a fictitious long-term wish list for a Reich intended to stand 1,000 years.

Huxley also satires the hubris of racism. When his protagonist visits the southwestern United States, they journey to a “Savage Reservation” where they encounter the supposed horrors of natural-born existence, including such weaknesses as aging, multilingualism, and religion—in other words, organic humanity itself.[9]

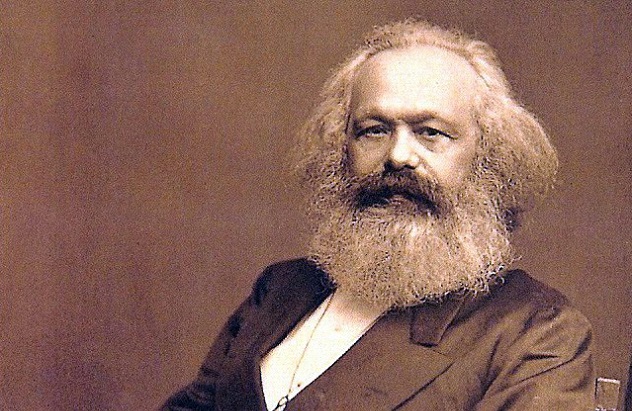

2 The Communist Manifesto (Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels)

It’s well known that Hitler despised communism, but less understood is precisely why. Considering that, by its very acronym (National Socialist Workers’ Party), Naziism purported to be a socialist movement, the two philosophies are sympatico on several issues, particularly concerning economics.

However, Hitler’s hatred of communism—and especially Soviet communism—was more visceral than political. In the 1920s, Nazi Party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg introduced him to Protocols of the Elders of Zion, among history’s most notorious antisemitic tomes. The fabricated narrative describes Jewish plans for world domination, exacerbating Hitler’s existing prejudices.[10]

When you’re as batsh*t nuts as Adolf Hitler, you find enemies everywhere. Noting the widespread Jewish participation in Russia’s 1917–1923 Bolshevik Revolution, Hitler foresaw the beginning of a Jewish takeover of Europe.

Compared to the increasingly warped characterizations since its 1848 publication, The Communist Manifesto is measured and reasonable. Dissecting society into “Bourgeois and Proletarians”—that is, upper and working classes—Marx and Engels contend that “the history of all existing hitherto society is the history of class struggles.” Complacency and divisions among the working class serve the upper class since the status quo favors them.[11]

While radical at the time, many of the manifesto’s demands are now fixtures of modern Western society. These include a progressive income tax, the abolition of child labor, free public education, and ample publicly owned land.

1 Everything (Institute of Sexology)

In the early 20th Century, Germany was at the forefront of tolerance. Go figure.

Founded in 1919 by Magnus Hirschfeld, a renowned expert in the emerging discipline of sexology, Germany’s Institute of Sexology earned a progressive reputation for its efforts to gain equality for women and homosexuals, as well as pioneering work toward understanding transsexuality. Among other initiatives, Hirschfeld fought for the repeal of an edict called Paragraph 175, which criminalized homosexuality in Germany.

Unsurprisingly, none of this flew with Hitler. Nor did the fact that Hirschfeld was gay, Jewish, and liberal—a trifecta of treachery as far as Nazis were concerned. So on May 6, 1933, four days before the scheduled May 10 pyromaniacal purge, members of the German Student Union loyal to the Nazi Party invaded and occupied the Institute (pictured above). They may or may not have received extra credit for this.[12]

Over the next few days, the Institute’s trove of texts was hauled to the book-burning site, where on May 10, they became a sizable portion of the fire’s macabre fuel. Hirschfeld was working in Paris at the time and learned of the event on a movie theater newsreel. Among the texts incinerated was Heinrich Heine’s Almansor, in which the author noted: “Where they burn books, in the end, they will burn humans too.”