History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

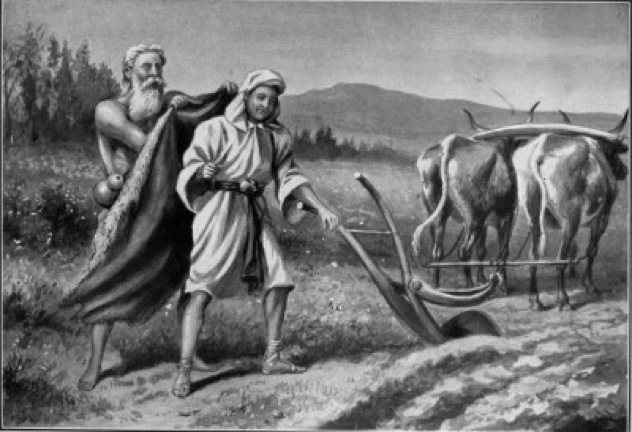

10 Biblical Figures Who Teach Outrageous Morals

There’s a reason the Bible is the best selling book in the world, and it’s not necessarily what you might think. A light in the lives of many, a moral compass to others, and a sweeping storybook no matter what you believe, the Bible has transcended generations. It may have more gratuitous sex and violence than an entire season of Game of Thrones, but that’s okay—it also teaches a code of ethics that anybody can find something to agree with. Unfortunately, many of the Biblical figures who are held up as righteous, honorable, and virtuous are responsible for some of the most heinous acts of immorality ever put down on paper. Here are 10 of them. For the sake of consistency all quotes are taken from the King James Bible.

Elisha was a prophet who is believed to have lived during the 9th century B.C. When Elijah, who was Elisha’s teacher, was called up to heaven, God commanded him to appoint Elisha as the new head prophet. He performed a good many miracles, such as conjuring water for the city of Jericho and bringing a woman’s son back to life, but there’s one “miracle” that really stands out. Sandwiched between various blessings and acts of kindness are two verses at the end of 2 Kings Chapter 2—verses 23-24—that seem so completely out of place you almost wonder if they were added as a joke. They weren’t.

Here’s what happened: Elisha was walking into the city of Bethel when a group of kids ran out and started making fun of his bald head. It’s the only mention in the Bible that Elisha was bald, which is probably good—because the next thing Elisha did was curse the children to death. Immediately, two bears ran over and tore the kids to pieces. The most important—most Godly—prophet in the land brutally murdered forty-two children because they laughed at him. He is now a venerated saint.

There’s a good chance you’ve never heard of Jael—her only role in the Bible was to secure a man’s trust before she killed him. Chapter 4 of Judges describes a battle between two generals: Barak, the general of the Israelite army, and Sisera, leader of the Canaanite army. The two armies met on a river bank and Holy war was waged, ten thousand men fighting ten thousand men. As the tide of battle turned in favor of Barak, Sisera decided to cut his losses and fled into the desert alone. Back at the battle field, the Israelites slaughtered every single Canaanite soldier (“and all the host of Sisera fell upon the edge of the sword; and there was not a man left”).

So Sisera was alone in the desert, and he came across a tent belonging to an ally of his, a man named Heber the Kenite. The man’s wife, Jael, ran out to greet Sisera and welcomed him into the tent, telling him he had nothing to be afraid of. She then hid him under a blanket (Barak was still chasing him), waited until he went to sleep, and then snuck up and hammered a tent spike directly through his forehead, nailing his head to the ground. And verily, through lies, deceit, and backstabbing, the hand of the children of Israel prospered.

King David is, arguably, the most righteous man in the Bible (even though he single-handedly killed and circumcised 200 men for a wife). When David’s son Solomon sidestepped the path of holiness, God decided to lessen his punishment because he had loved David so much. But as several of these examples are going to show, brutality and mass genocide go hand-in-hand with righteousness, and it’s usually the righteous man that leads the slaughter.

In 1 Samuel 27:8-11, David takes an army and invades several neighboring lands. The Bible doesn’t give any reason for him to do this, other than a side note that the people he killed were “of old the inhabitants of the land,” so it seems he was just wiping out the indigenous people. David’s army killed all the men and women in the towns he defeated, then carried all the livestock back to their own land, leaving the towns in ruin.

Even the story of David and Goliath that’s usually told to kids ends before it gets too violent—after David kills Goliath with a stone, he chops off the man’s head and carries it around with him.

Samson was a man to whom God granted superhuman strength to help him destroy the evil Philistines (the Galactic Empire of the Bible). However, he would only have his strength as long as he didn’t cut his hair. Even from the perspective of “a righteous hero that destroys the evil tyrant,” Samson really just brings everything on himself, and then can only get himself out of trouble by killing more and more people, like a little white lie that won’t go away. From any other perspective, he’s a murderous psychopath.

In Judges 14:12-19, Samson makes a wager with thirty men that none of them will be able to guess his riddle; if they do, he’ll give them thirty silk shirts. Lo and behold, they trick his wife into telling them the answer, so Samson, not one to shirk on a debt, takes the honorable route: he runs out and kills thirty men, steals their clothes, and pays the men. This delightful children’s video lightens the mood with an upbeat song. But remember, he murdered thirty men; that’s only five short of Ted Bundy status, and it doesn’t even count the 1,000 he killed later with a donkey bone.

We mentioned Elijah earlier; he was the prophet who appointed Elisha to take his place before God sent a flaming chariot to lift Elijah into heaven. Needless to say, he was fairly holy. During the time that he was a prophet in Israel, there came a period when many of the people began to worship Baal, a heathen god. Elijah was perturbed at this turn of events, and decided to prove himself to the Israelites.

In 1 Kings 18:19-40, he called together 450 of the prophets of Baal and gave them a challenge: Kill a bull and put it on an altar, then pray to Baal to light the altar for you. They prayed for hours but nothing happened, so Elijah took a turn. He killed a bull and set up an altar, then prayed to God to light it. Boom, instant fire. The Baal prophets immediately converted to believers, but Elijah wasn’t satisfied. So he took them all down to a river and systematically executed every single one of them.

Elijah actually spent a lot of time proving how holy he was—in 2 Kings 1:9-14, fifty men were ordered to come bring Elijah to the king. Elijah said, “If I be a man of God, let fire come down from heaven and consume thee and thy fifty.” So he killed them all, then did the same with the next hundred men who came for him.

Jephthah was the son of Gilead, a wealthy man, but his mother was a harlot (whore), which meant that he was doomed to be ostracized. True to form, Jephthah was kicked out of his home with no inheritance as a young man (“thou art the son of a strange woman”). After several years had passed, the Israelites went to war (or kept being at war—they were at war a lot). They sought out Jephthah and asked him to return to Gilead, and from there lead their armies into battle against the Ammonites. At this point the king of Ammon asked Israel to just let them live peacefully, and the Israelites’ reply pretty much summed up the reasoning behind every holy war up through the Crusades: “Whomsoever the Lord our God shall drive out from before us, them will we possess.”

So Jephthah led the charge, but before the battle he made a bargain with God: Let us win, and I’ll sacrifice the first thing that greets me at my home when I return. God kept his side of the deal, and when Jephthah returned home his daughter ran out to meet him. And Jephthah kept his side of the bargain too—he performed a ritual sacrifice of his daughter, his only child, to pay back God.

Jehu became the king of Israel after a violent coup overthrew the previous king, King Jehoram. In the aftermath of the battle, Jehu hunted down and killed all of Jehoram’s royal family and had their heads—seventy of them—piled outside the city gates. Then he ran over Jehoram’s mother in his chariot. But wait, wait until we get to the brutal part.

As the new king, anointed by the prophet Elisha, Jehu had some house cleaning to do. According to 2 Kings 10:18, Jehu put out a fake rumor that he was a Baal worshiper, and asked for all the Baal worshipers in the kingdom to come to a massive sacrifice in his honor. When the people came from throughout the kingdom they were ushered into the house of Baal; it doesn’t say how many there were, but the house of Baal was “full from one end to another.” With every single member of the religion safely clustered in the church, Jehu ordered his army to storm in and massacre them all. That’s one of the literal definitions of genocide. God rewarded Jehu by granting his next four generations a guaranteed seat on the throne of Israel.

The story of how Joshua destroyed the walls of Jericho with the blast of trumpets is the stuff of legend. Elvis can tell you all about it. But like most good Sunday school stories, the genocide comes later. Because once those walls came a-crumbling down, Joshua’s army entered the city and killed the men, women, and children without distinction—”both man and woman, young and old, and ox, and sheep, and ass, with the edge of the sword.”

What the story doesn’t tell is that this wasn’t an isolated battle; Joshua was on a zealous tirade all across Israel. Here are five meaningless words: Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron, Debir. Each one of those is a city filled with people which, according to Joshua Chapter 10, the army of Joshua completely devastated. He “utterly destroyed all that breathed.”

Moses is most famous for leading the Israelites out of Egypt; the book of Exodus covers the big stories—the ten plagues, the parting of the Red Sea, and receiving the Ten Commandments from God (thou shalt not kill, etc.). It’s Numbers, however, that covers the forty years in the wilderness (which was literally a punishment for not wanting to attack a city). And rather than wandering, the Israelites spent much of this time invading other cities.

After a victorious battle against the Midianites, Moses gave the following ludicrous order: “Now therefore kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman that hath known man by lying with him. But all the women children, that have not known a man by lying with him, keep alive for yourselves.” (Numbers 31:17-18). This is literally permission to rape all the little girls in the Midianite cities.

So far we’ve seen nearly a dozen cities completely ravaged and all the inhabitants put to death. We’ve seen commands for rape, religious genocide, the killing of children, and human sacrifice. What we haven’t seen are the burning of whores, a ban on crippled people, or the killing of 70,000 men. There are 134 words in this paragraph, and if we linked a verse on every single word, it wouldn’t even begin to scratch the surface of the acts committed either by God’s hand or under His command that would be considered immoral—or blatantly insane—by today’s standards. But that’s the thing, right? Today’s standards are held to a different moral code than the standards of the 800 years or so before the birth of Christ. But, then again, how does that make any sense?