History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

10 Obscure Historical Events That Would Make Amazing Movies

There’s a lot of history, and we’re making more every year. As a result, many history textbooks have to focus on the grand sweep of events rather than individual stories. This is understandable but a shame since it means missing some of the most amazing stories of our shared past.

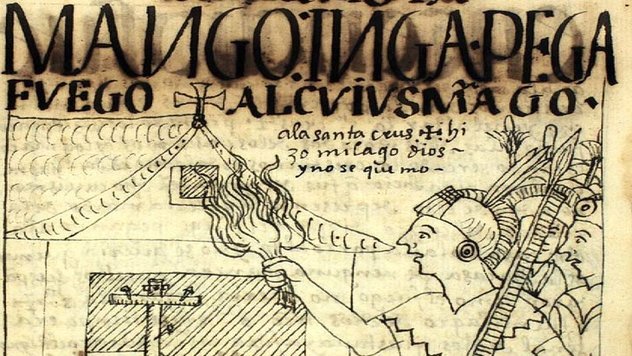

10I Am Manco Inca

Parts of the Incan conquest are well-known. The Spanish arrived in Peru to find the empire racked by smallpox and devastated by a civil war, which the Inca Atahualpa had just won. Although outnumbered, Pizarro’s men captured Atahualpa, ransomed him for a room full of gold, and then strangled him anyway, taking control of his empire in the aftermath. Most history books stop there. But they shouldn’t.

After Atahualpa’s death, the Spanish crowned his young brother, Manco, as their puppet emperor. They treated him terribly, with Francisco Pizarro’s brother Gonzalo even abducting and raping his wife. Little did the Spanish realize that the frightened teenager would soon become their deadliest enemy.

In 1535, Manco tried to escape from Cuzco, where he was a virtual prisoner, but he was captured and dragged back into the city behind Gonzalo Pizarro’s horse. As punishment for the escape attempt, he was beaten, urinated on, and imprisoned in chains. In 1536, he persuaded his captors to let him leave the city by promising to show them to a golden statue of his father. As soon as he was clear of the city, he escaped again. He would never be recaptured.

Instead, he summoned all the ancient forces of the Inca. With at least 50,000 men, he besieged Cuzco, killing Juan Pizarro. Francisco Pizarro was at Lima and quickly sent reinforcements, but they were ambushed in a gorge by Manco’s general, Quizu Yupanqui, who crushed them with rockslides. A few weeks later, Yupanqui wiped out a second Spanish column, then captured the city of Jauja and slaughtered its garrison. Massing his forces, he attacked Lima itself. For a moment, the Spanish conquest hung by a thread.

The thread held. A surprise cavalry charge broke Yupanqui’s forces just as Lima was about to fall. The general was killed, and reinforcements forced Manco back from Cuzco, devastating his forces. But Manco Inca wasn’t defeated so easily. He retreated into the Amazon to the most isolated corner of the Inca state. There, in the jungle city of Vilcabamba, he formed a rump empire from which he launched attacks against the Spanish.

Obviously, this was unacceptable, and Gonzalo Pizarro was sent to attack Vilcabamba with a strong force in 1539. He sent two of Manco’s brothers ahead of him to negotiate. Unimpressed by such treachery, Manco had them both beheaded. Despite heavy casualties, the Spanish pressed on to Vilcabamba, where they were greeted by gunfire from warriors trained by Manco’s Spanish captives. But the warriors were not yet proficient with the guns, and the city fell. Manco himself was rushed to safety across a river.

Shivering on the bank, surrounded by a handful of painted jungle warriors, Manco Inca paused. The son of Huayna Capac, divine heir to a great empire, who had grown up in a palace in Cuzco, walked back to the river and shouted across at his pursuers: “I am Manco Inca! I am Manco Inca!”

Then he disappeared into the jungle, where he and his sons fought until 1572.

9The Man With the Iron Hand

Henri de Tonti is best remembered today as the insanely competent sidekick of bumbling French explorer Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. Born in Italy, Henry was the son of Lorenzo de Tonti, the inventor of the tontine, a type of fund where the initial investors split the returns between them until all but one investor dies. At that point, the last surviving investor gets the whole fund. For obvious reasons, it’s now mostly found in murder fiction.

After a failed rebellion in Naples, the family fled to Paris, where Henri joined the military, fighting in several conflicts across Europe. In Sicily, his hand was blown off by a grenade (legend says he personally hacked the mangled remains off), and he replaced it with an iron prosthesis, which he covered with a glove. (A 16th-century iron hand is pictured above.) Later in life, he would use his metal appendage as a weapon against anyone who challenged him, earning the nickname “Iron Hand” from Native Americans impressed by his ability to knock people unconscious with a single blow.

And the non-metal parts of Tonti were just as tough. At Cavelier’s bidding he single-handedly built the first European ship to sail the Great Lakes. He explored the Mississippi River, made peace between the Choctaw and Chickasaw, and declared himself lord of the “river of Arkansas.” When Cavalier finally vanished (his own men murdered him), Tonti led an expedition looking for him.

Around 1680, Tonti was living among the Illinois, having been deserted by all but five of his men. When the powerful Iroquois Confederacy attacked, Tonti decided to go and negotiate with them, which was a bold move considering a battle was already raging around him. When he attempted to walk over to the Iroquois, they opened fire, prompting his companion to run away. But Tonti kept going through the hail of bullets until he arrived among the surprised Iroquois. Who promptly stabbed him in the chest.

Most people would have taken the hint, but Tonti just started threatening war with France unless the Iroquois backed off. Although one chief suggested burning Tonti to death and another warrior kept lifting his hair to scalp him, cooler heads prevailed, and he was allowed to leave. He walked all the way back to camp, despite “the great quantity of blood I had lost, both from my wound and my mouth” and subsequently bluffed the Iroquois into signing a peace treaty. He died in 1704 and his remains were “laid to everlasting rest in an unknown grave near Mobile River.”

8John Smith’s Real Romance

Fans of Disney movies will know of the brave Captain John Smith and his romance with Pocahontas. And fans of popular list-based websites will know that it’s extremely unlikely that romance ever happened. But don’t despair—John Smith did have a daring romance with a powerful local woman. It just didn’t involve Pocahontas.

Before he journeyed to America, Smith was a pirate-turned-mercenary fighting the Turks in the Balkans. According to his enormously entertaining memoirs, he even defeated three Turkish champions in single combat. (He used a coat of arms with three Turkish heads on it for the rest of his life.) Unfortunately, Smith’s luck ran out, and he was captured and sold into slavery.

Things were looking dark, but Smith’s new master sent him to work for his Greek mistress, Charatza Trabigzanda, who quickly fell madly in love with her handsome new servant. Worried that her overbearing mother would sell Smith, she sent him to her brother’s Black Sea farm, where she instructed him to learn Turkish and wait until she was out from under her mother’s thumb. But Charatza’s brother didn’t approve of the relationship and decided to work Smith to death instead. Malnourished and desperate, Smith eventually snapped, beat his boss to death in a wheat field, and escaped into Russia on his stolen horse.

Smith’s exploits attracted an invite to help establish a colony in America. Typically, he was arrested for mutiny on the way there, barely avoided hanging, and was running the entire colony within a year. After not romancing Pocahontas, he returned to England to recover from a gunpowder accident that probably blew his genitals off. For years, historians assumed his memoirs were total fiction, but recent work actually corroborates some details. As historian Philip Barbour put it, “let it only be said that nothing John Smith wrote has yet been found to be a lie.”

7Mustapha Cons His Way to Freedom

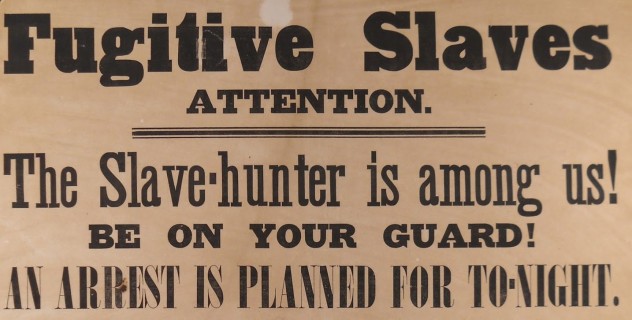

Of course, escaping from slavery was easier said than done, particularly for slaves who lived in the American South, miles from safety in the North. Field slaves often had little in the way of cash to sustain them through an escape like the one pictured, not to mention the bands of bounty hunters that would surely be hot on their heels. Henry “Box” Brown solved the problem by mailing himself to safety, but perhaps the most satisfying escape was made by a slave known only as Mustapha, who teamed up with a white hunchback named Arthur Howe and conned his way to freedom.

The plan was simple, the pair traveled through North Carolina and Virginia, telling anyone they met that Mustapha was Howe’s slave. Since Howe was famous for his fearsome appearance, “expressive of dark angry passions,” few decided to ask any more questions. Whenever they reached a town, Howe would sell Mustapha for a tidy fee. After a few days of recuperating, Mustapha would escape again, and the partners would resume their journey. Not only did this help avoid bounty hunters—who would be looking for an escaped slave rather than a current one—it netted a tidy profit as well. It also says something about Mustapha that he had no worries about his ability to escape from everyone he was sold to. Most slaves struggled to escape once; Mustapha did it every week.

The pair apparently planned to part ways after reaching Petersburg or Richmond, leaving Mustapha free to make his escape north. Since he was not apprehended, this is presumably what happened, although the duo drops out of history after that. Still, why hasn’t Hollywood jumped all over the story of a crazy-eyed hunchback and an escape-artist former slave forming an odd-couple partnership to rip off every slave owner on the road to freedom?

6The Great Courtroom Body Swap

Even escaping to the North wasn’t a guarantee of safety for former slaves. Just ask Lewis Williams, who escaped and built a new life in Cincinnati, only to be tracked down by his former master. Under the laws of the time, Williams could legally be returned to slavery, although a judge had to sign off on the extradition request. But as Williams was escorted to the courthouse, the local abolitionist community was already swinging into action.

Led by an African-American preacher named William Troy, the freedom-loving inhabitants of Cincinnati poured into the courtroom, packing it to bursting. But they weren’t just there to offer moral support. With the marshals distracted by the case, Williams switched places (and hats) with a similar-looking young man and crawled out of the courtroom on his hands and knees. Apparently, it took some time before anyone realized that the person on trial was no longer Lewis Williams.

But things weren’t over there. Williams was hiding out in Troy’s house, which was soon surrounded by the police. So the cunning reverend simply disguised him in women’s clothes, including a bonnet and a “whopping” crinoline. Williams then spent the day being trained to walk like a woman before sauntering out the back door, waltzing past the watching policemen, and hopping on a train to Canada.

5General Dumas Holds the Bridge

As the author of The Three Musketeers and The Count Of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas is one of the most famous writers in history. But while Alexandre just wrote about daring adventures, his father actually lived them. Thomas-Alexandre Dumas was born in Haiti to a French nobleman and his slave concubine. His early life was rough—at one point, his father even sold him as a slave to get a ticket back to France. However, his father eventually inherited a fortune and bought him back, bringing him to France and educating him as a gentleman.

Thomas-Alexandre grew up to be the leading swashbuckler of the period, famous for his incredible strength and skill with a sword. It was said that he even fought three duels in one day, inspiring the famous meeting between d’Artangnan and the musketeers. But prospects for a black man were still limited at the time, and Dumas eventually decided to join the army as a humble private.

That turned out to be a good decision since the French Revolution soon made wealthy nobles unfashionable. Inspired by talk of liberty and equality, as well as the decision to emancipate France’s slaves, Dumas soon became one of the revolution’s fiercest champions. In 1791, he was a corporal. By 1793, he was a general leading 10,000 men into battle. In 1794, he risked his life by defying orders to launch a campaign immediately. In explanation, he wrote that “it is the responsibility of the man in charge to prepare with caution and wisdom everything that leads to victory.”

But while Dumas was cautious with the lives of his men, he was pathologically brave with his own. In 1795, the French army found itself pinned down by the Austrians, unable to reach a strategically vital bridge. So Dumas rallied 30 dragoons and charged the bridge himself. Under withering fire, he used his insane strength to hurl the Austrian barricades into the river and charged across the bridge. Surrounded by three Austrians, he took a saber to the shoulder but managed to draw his pistol and fight his way clear.

Eventually, Dumas and his aide Dermoncourt found themselves virtually alone. Dumas was bleeding from multiple injuries but managed to keep fighting, battling hand-to-hand against waves of Austrian cavalrymen. As Dermoncourt collapsed from his wounds, he turned and saw General Dumas: ”he was standing at the head of the bridge of Clausen and holding it alone against the whole squadron; and as the bridge was narrow and the men could only get at him two or three abreast, he cut down as many as came at him.”

Amazingly, Dumas held out until reinforcements arrived, although his injuries would dog him for the rest of his life. He next commanded the cavalry during Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt but fell out with Bonaparte, a blatant racist who disliked being overshadowed by Dumas. Returning to Europe, his sinking ship was forced to land in enemy territory, where he was held captive in circumstances that inspired the Count of Monte Cristo. He died in 1806 when his son was just four years old.

4Nellie Bly’s Trip Around the World

On Nov. 14, 1889, journalist Nellie Bly set out to circle the globe, seeking to beat the fictional record set by Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days. Sick of the daily grind at her newspaper job, Nellie Bly conceived of the trip after reading the book, so she pitched the idea to her editor at the New York World newspaper. Bly eventually got the green light for the journey and had to prepare in two days.

Bly mapped out her route but purchased a ticket only for the first leg of her journey so that she could adjust her travel schedule at any time. On Nov. 14, 1889, she left her home in New York with a single suitcase and boarded a ship for London. After arriving in London, she took a train to Paris. While in France, she met Jules Verne, who challenged her to make the trip in 79 days.

She continued on her way through Italy before taking a steamer ship to the Suez Canal and Egypt. She sent updates back to her newspaper, who ran the stories and offered a contest for a free trip to Europe for whoever guessed how long Bly’s trip would take. To take advantage of the hype, a rival newspaper sent their own female reporter to make the same trip, just in the opposite direction. The two reporters actually met in Japan and exchanged some words…and a challenge.

Bly traveled by ship, train, jinricksha, sampan, horse, and burro to reach her goal. A cheering crowd welcomed her as she returned to New York on Jan. 25, 72 days, 6 hours, and 11 minutes after first setting sail on her nearly 25,000-mile journey across four continents.

3The Prince and the Pauper, From Paris to Peking

In 1907, a French newspaper asked its readers if there was “anyone who [would] undertake to travel this summer from Paris to Peking by automobile” and started perhaps the greatest race in history. Only five contestants entered, including a three-wheeled “tricycle” which broke down in the middle of the Gobi, where it presumably remains. (Nomads rescued the crew.)

But the leading contender was the Italian Prince Scipione Borghese, the scion of a noble family who drove a magnificent 40 HP Itala, complete with a supply of champagne. His great rival was a convicted French con man named Charles Godard, who had been eking out a living performing “Wall of Death” motorcycle tricks in a circus when the wind blew a newspaper article about the race at his feet. Although he had never driven a car before, Godard became determined to enter the race. Since he didn’t have any money, he returned to fraud to acquire a car but still had to pay for his passage out by playing the piano on the boat to China. He also had to sell most of his spare parts.

The 16,000-kilometer (10,000 mi) race passed through some of the most isolated regions of the world. At one point, Borghese came across an isolated telegraph office and tried to send a message home. It was the first telegraph the office had sent in six years. On another occasion, his car almost went through a wooden bridge, dangling precariously until some locals arrived and pulled it to safety. Still, the prince was so confident that he detoured to St. Petersburg to attend a dinner. Meanwhile, Godard was begging fuel from his competitors and driving for 24 hours at a time in a desperate attempt to catch up. In the end, Borghese won the prize: a magnum of champagne. Godard was arrested for fraud as soon as he arrived in Paris.

2The Bizarre Fall of Fort Sumter

It’s well known that the U.S. Civil War began when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter (pictured above in 1865). What isn’t often discussed is just how much of a farce the whole thing was. For starters, the Confederates actually opened fire on the fort a month before the war began, then had to row over and apologize for the inexperienced gunner who had accidentally discharged his cannon. The practice apparently didn’t help since when the war started for real, they fired over 3,000 shells at the fort without injuring a single Union soldier.

Still, the fort surrendered, and a Confederate officer named Richard Pryor rowed out to negotiate the terms. As the discussion progressed, Pryor casually got up, poured himself a glass of whiskey, and downed it in one gulp. Unfortunately, the “whiskey” was actually a bottle of medical iodine that happened to be nearby. Pryor’s Three Stooges moment ended with army doctors frantically pumping his stomach while nervous Union officers wondered how they would explain poisoning the negotiator.

Fortunately, Pryor survived, but there was still time for one last screw-up. To mark the surrender, the Union commander ordered his gunners to fire a salute. The careless gunners piled cartridges right next to their cannons in a high wind, causing an explosion that killed two of their own men, the only casualties of the siege.

In fact, the buildup to the war was generally more farcical than you’d imagine. In 1858, tensions between pro- and anti-slavery factions were so heated that a huge brawl broke out between at least 30 Congressmen on the House floor. The melee only came to an end when Mississippi’s William Barksdale had his wig knocked off. Since Barksdale never admitted to wearing a wig, he quickly snatched it back up and put it on inside out, causing everyone to stop fighting and start laughing instead.

1The Last Ride of Iron Jacket

In the 18th and 19th centuries, European settlement expanded westward across America in a steady wave, overwhelming ancient and storied tribes like the Iroquois, the Cherokee, and the Shawnee. Then it reached Texas and the lands of the Comanche and briefly stopped dead.

The Comanche were an obscure mountain tribe until the horse arrived in North America, but they took to the animal like no other Native American group. The horse allowed them to become nomads, following the buffalo, and they exploded across the Texas plains, virtually wiping out the Apache in the process. Their enormous horse herds were legendary, as were their riding skills. While the Cheyenne and Sioux would dismount before battles, the Comanche mastered the art of fighting on horseback. They planted no crops, built no settlements, and shunned complex rituals or religion. The name “Comanche” was given to them by the Utes. It means “enemies.”

When American settlers arrived in Texas, conflict was inevitable. The Comanche were outnumbered almost from the start and generally avoided direct conflict. Instead, they preferred to raid undefended farmhouses, slaughtering the inhabitants. It worked, grinding European expansion almost to a halt. In 1858, after a particularly bloody year, the Texas Rangers were ordered on an unprecedented raid. Their target was the Comancheria, the empire of the Texas plains, a brutal and unchanging grassland of deadly heat, vast wildfires, and sudden snowstorms. Three hundred years earlier, the explorer Francisco de Coronado was lured there by hostile natives, who expected him to die. He wrote that “although I traveled for more than 300 leagues, [there were] no more landmarks than if we had been swallowed up by the sea.”

No European had penetrated far into the Comancheria, but now the Rangers intended to do just that. They were accompanied by a group of Tonkawas, a local tribe hated by other Native Americans for their cannibalism. The Comanches slaughtered the Tonkawas whenever possible, and the survivors longed for revenge. Together, the Rangers and the Tonkawas traveled for weeks, fording stretches of pure quicksand, until they discovered a huge Comanche camp stretching along a creek in the Antelope Hills. The Comanches sprang onto their horses, but they never expected to be attacked in the heart of the Comancheria and were in no position to fight.

Then, Chief Iron Jacket rode out of the chaos. His true name was Pobishequasso, but he was known as Iron Jacket for his ancient coat of Spanish armor, a family heirloom looted from the corpse of some unlucky conquistador. He exhaled great breaths of air as he rode toward the Rangers, working his medicine, which was said to blow bullets off target. The Rangers and the Tonkawas opened fire, but Iron Jacket kept coming. The bullets seemed to bounce off him. For a moment, he was unstoppable.

Then, as it always does, the magic ended. A hail of rifle fire cut down his horse, and a second volley finished Pobishequasso. His followers (armed only with lances and ancient muskets) fled, pursued by the Rangers, who picked off at least 76. In the years that followed, the settlers became bolder, launching numerous raids into the Comancheria. Iron Jacket’s rusting armor was broken up for souvenirs. It wasn’t the end, but it was the beginning of it.