Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Creepy

Creepy 10 Shocking Tales of Bodies Found in Abandoned Houses

Politics

Politics Top 10 Surprising Facts from the Life of Jimmy Carter

Sport

Sport 10 Popular but Terrible Goalkeepers

Technology

Technology The 10 Most Compelling Aircraft That Didn’t Succeed

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Ridiculous Riffs on Robin Hood

Technology

Technology 10 Extreme Structures We Might See in the Future

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Catastrophic Translation Fails in History

History

History 10 Wild Facts About the Mutiny on the HMS Wager

Our World

Our World 10 Secrets Places You Won’t Believe

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Fascinating Origins of New Year’s Eve Superstitions

Creepy

Creepy 10 Shocking Tales of Bodies Found in Abandoned Houses

Politics

Politics Top 10 Surprising Facts from the Life of Jimmy Carter

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Sport

Sport 10 Popular but Terrible Goalkeepers

Technology

Technology The 10 Most Compelling Aircraft That Didn’t Succeed

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Ridiculous Riffs on Robin Hood

Technology

Technology 10 Extreme Structures We Might See in the Future

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Catastrophic Translation Fails in History

History

History 10 Wild Facts About the Mutiny on the HMS Wager

Our World

Our World 10 Secrets Places You Won’t Believe

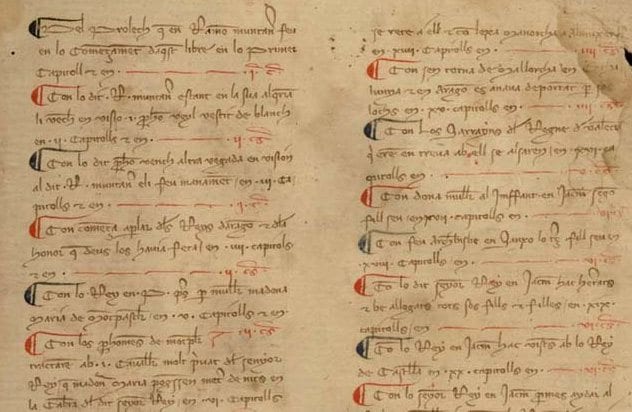

10 Bizarre Crusades Forgotten By History

In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church developed the concept of a holy way in which the participants would receive pardons for their sins. These became known as “crusades.” The crusades in the Holy Land are well known, and the crusades against pagans in the north at least somewhat remembered, but the Church launched a wide variety of other crusades, some of which are now all but forgotten.

10The Crusade Against Markward

The crusades arguably went off the rails with the crusade against Markward of Annweiler. A thoroughly anticlimactic and forgotten event, it seems to have been the first time a Pope declared a crusade with an obviously political motivation, rather than any religious justification.

After Emperor Henry VI died, his infant son was declared king of Sicily, which was entrusted to the care of Pope Innocent III. However, Henry’s steward Markward of Annweiler claimed that Henry had made him regent of Sicily in his will. Markward occupied the island against the wishes of the Pope, who declared a crusade against him.

This was a thoroughly unpopular move, since Markward was a non-heretical Christian who had participated in the Third Crusade. A crusader army was nonetheless raised under Walter of Brienne, but the matter was resolved when Markward suddenly died. Despite this undramatic ending, the incident provided justification for numerous other political crusades.

9Humbert’s Crusade

In 1343, Pope Clement VI organized a crusade by the Venetians and Hospitallers to capture the Turkish city of Smyrna. The expedition went badly, and Clement soon preached a more general crusade, calling on the nobles of the West to march on Smyrna. This impassioned call was met by a resounding “meh.” In fact, the only volunteer seems to have been Humbert, the young and excitable Dauphin of Viennois.

Humbert was promptly declared commander of the crusade and sailed for Turkey with around 900 men. In the Aegean, the tiny crusade was attacked by the Genoese, who suspected Humbert was planning to assault the island of Chios.

Humbert finally arrived in Smyrna in 1346, only to find that the earlier expedition had crumbled into infighting between the Hospitallers and the Venetians. Thoroughly disillusioned, the youth packed his crusade back up and returned to Europe.

8The Battle Of Nicopolis

After the Ottomans crossed into Europe, the alarmed Hungarians called for a crusade. At the time, the Catholic Church was split between feuding popes in Rome and Avignon, but they both agreed to declare a crusade, and an expedition against the Turks was duly organized.

The 100 Years War was on hiatus at the time, and many young French and Burgundian nobles volunteered to prove their mettle against the infidels. The 24-year-old son of the Duke of Burgundy was elected leader, and the expedition became something of a competition for which wealthy young crusader could outfit the most opulent retinue.

After reaching the Balkans in 1396, the crusaders attacked Muslims and Orthodox alike before encountering the army of Sultan Bayezid the Thunderbolt at Nicopolis. The Hungarians urged a defensive approach, but the westerners rejected such a cowardly strategy. Instead, the splendidly armored knights charged wildly up a steep hill at a fortified position. They were promptly slaughtered, ending the crusade at a stroke.

7The Stedinger Crusade

The Stedingers were a group of freethinking peasants from northern Germany who refused to pay tithes or perform unpaid labor for the Archbishop of Bremen. The infuriated archbishop raised an army to deal with the rebellious commoners, but the Stedingers defeated it in 1229.

The archbishop decided to escalate matters by accusing the Stedingers of heresy and asking the pope to preach a crusade against them. In fact, the Stedingers were not heretical in any meaningful sense. They just didn’t want to pay taxes to the bishop. Nonetheless, Gregory IX declared a crusade against the peasants in 1232.

Several bishops and Dominican friars were commissioned to preach the crusade, and all who fought in it were to be granted full indulgences and forgiveness for their sins. The Stedingers defeated one crusader attack, but a fresh army crushed the peasants in 1234, bringing the crusade to an end.

6The Anti-Colonna Crusade

In the late 13th century, Rome was split between three feuding families: the Orsini, the Caetani, and the Colonna. In 1294, the Orsini and the Caetani teamed up to have Benedetto Caetani elected as Pope Boniface XIII. This infuriated the Colonna, who robbed the papal treasury in 1297. Pope Boniface responded by abducting cardinals Giacomo and Pietro Colonna until their relatives returned the loot.

Although they gave back the money, the Colonna were infuriated by the incident and became increasingly vicious in their attacks on the Caetani. They accused Pope Boniface of heresy and murdering his predecessor. In response, the Pope demoted the Colonna cardinals and declared a crusade against the family.

After being driven out of Rome, the Colonna teamed up with the French king to launch an attack on the Pope at his home in Anagni. During the attack, the French had to stop Sciarra Colonna from beating the Pope to death. Boniface was soon freed by an angry mob, but the incident took its toll and the Pope died days later, ending the anti-Colonna crusade.

5The Italian Crusades

Although the Colonna Crusade was inconclusive, the Popes continued to get caught up in petty Italian politics and preached crusades against their temporal enemies repeatedly throughout the 14th century.

In 1309, a dispute over the city of Ferrara led to a crusade being declared against Venice, although the Venetians backed down before it went anywhere. In 1317, a crusade was declared against the Estensi of Ferrara and the Visconti of Milan, along with Frederick of Montefeltro. The fighting raged inconclusively for years, and the crusade was extended to the city of Mantua in 1324 and Emperor Louis IV in 1327.

In 1355 a crusade was declared against several noble families of the Romagna, who were defeated by Cardinal Gil Albornoz over the next two years. Yet another crusade was declared against the Visconti in 1363. These wars were fought mainly by mercenaries, who nonetheless were granted full forgiveness for their sins and other crusader indulgences.

4The Aragonese Crusades

Pope Martin IV was effectively a puppet of the French royal family, a branch of which also ruled Naples and Sicily. When Peter of Aragon invaded Sicily, Martin excommunicated him and ordered him to hand the kingdom of Aragon over to a French prince. When Peter disobeyed, the Pope declared a crusade against Aragon.

Although supposedly a holy war, the Aragonese Crusade was entirely a French affair. Philip III of France marched across the Pyrenees with a huge army and besieged Girona. However, the Aragonese defeated the French navy, cutting their supply lines. Then dysentery broke out in the French ranks, infecting even the king.

Terrified of dying on a latrine, Philip III ordered the crusade to retreat back across the Pyrenees. The Aragonese attacked the malnourished army in a mountain pass, slaughtering many of them. Philip himself was granted safe passage to Perpignan, where he soon expired.

3The Trade Crusade Of Alexandria

Peter de Lusignan was king of Cyprus, effectively the last major crusader state. In the 1360s, he traveled extensively throughout Europe, seeking support for a crusade against Egypt. Gaining the support of the Pope and fleets from Venice and Genoa, he attacked Alexandria in 1365.

Peter’s supposed plan was to conquer Egypt, which seems bafflingly unrealistic with the resources available to him. Several historians have since argued that he was motivated by economic concerns. Italian merchants had started buying eastern goods direct from Alexandria, and Peter may have hoped to shift the trade routes back through Cyprus by destroying the city.

In any case, after occupying and looting Alexandria, the crusaders withdrew when they heard the main Egyptian army was approaching. Venice and Genoa subsequently made full apologies to the Egyptians for participating.

2The Contra-Catalan Company Crusade

In 1303, the Byzantine Empire hired a group of mercenaries known as the Catalan Company, led by an ex-pirate named Roger de Flor. An impressive series of twists and betrayals ensued, including the murder of Roger and the failed siege of Constantinople by his mercenaries.

By 1311, the Company had crossed over into Greece, where they defeated Duke Walter of Athens and took control of his duchy. Though they had also seized Athens by force after the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, Walter’s family were outraged and appealed to the Pope.

A crusade was formally declared against the Catalans in 1330, on the grounds that they had usurped the Duchy and were overly friendly to the Turks. It did not achieve popular support and the Catalans continued to rule Athens for another 50 years.

1The Waldensian Crusade

The Waldensian Crusade was a tiny and unedifying affair that was effectively the last crusade of the Middle Ages. The Waldenses were a Christian sect who emphasized the holiness of poverty and were declared heretical in the 12th century. They hung on tenaciously and could still be found in southern France and Northern Italy in the late 1400s.

In 1487, Pope Innocent VIII declared a crusade against the Waldenses in the Dauphine. The Waldenses took refuge in the Alps and fought back, leading to several crusader assaults on fortified mountain caves. Peter Lock sums up this final anti-heretic crusade as “a small-scale event [which was] characterized by violence and rapine and achieved nothing.”