Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Historical Doctors Who Turned To Murder

There are few people in this world whom we trust more than doctors. We give them power over life and death and assume that they always have our best interests at heart. Sometimes, though, that’s just not true.

Some of the most proficient serial killers in history have been doctors or nurses. To people like Harold Shipman and Michael Swango, hospitals were just a way of gaining easy access to unsuspecting, trusting victims. Going back in time a century or two, we see that the medical profession had its fair share of depravity and murder even then.

10 The Brighton Murder

In June 1866, Dr. Alfred William Warder and his wife, Helen, checked into the Bedford Hotel in Brighton. Almost immediately, she fell ill. Worried by her condition, her brother, Mr. Branwell, asked a local physician named Dr. Richard Taaffe to examine her.

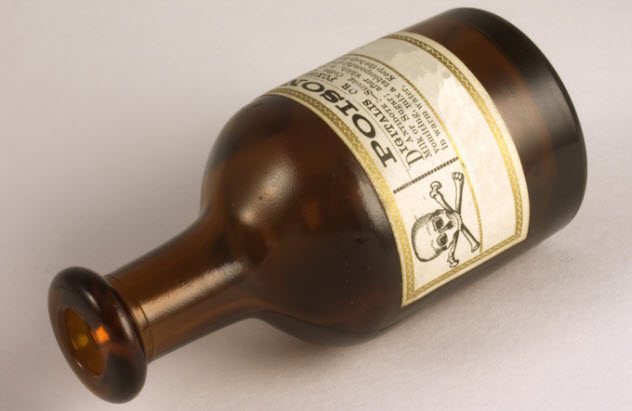

Taaffe was surprised to hear that Warder was treating his wife’s bladder pain with 20-drop doses of Fleming’s tincture of aconite.[1] Taaffe changed her prescription but never knew if the London doctor followed his instructions or not. Mrs. Warder died a few days later.

At this point, both Branwell and Taaffe expressed their concerns that there were no natural causes for Helen Warder’s untimely death. Strangely, Dr. Warder had no objection to a postmortem analysis, even though it found conclusive evidence of poisoning. In July, the papers branded him guilty of “willful murder,” but the case never went to trial. He committed suicide in his hotel room by drinking prussic acid.

Subsequently, it was speculated that Helen was not Dr. Warder’s first victim. She was his third wife, and the first two had both died under suspicious circumstances.

9 The Playboy Poisoner

Back in 1915, Hannah Peck was worried about the lack of suitors for her daughter, Clara, in their hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Therefore, when former schoolmate Arthur Warren Waite started wooing her, it was a joyous occasion for the family. After all, Waite was young, handsome, and had a successful dental practice in New York City. The two married in September and moved to Manhattan.

As it turned out, Arthur was more interested in leading a playboy lifestyle consisting of affairs and tennis tournaments and saw Clara’s inheritance as the best way to do it. Her father, John Peck, had a successful drugstore in Grand Rapids which he had parlayed into a fortune worth millions of dollars.

Waite wasted little time and, in January 1916, invited his mother-in-law to visit. She fell ill hours after arriving and died days later. In March, John Peck came to stay with them and also died within days. Waite would have gotten away with it if not for a mysterious telegram sent to the Pecks’ son, Percy, which said: “Suspicions Aroused Demand Autopsy.”[2]

Hannah Peck had already been cremated, but Percy obtained his father’s body despite Waite’s objections. The autopsy found arsenic and chloroform, and the dentist was arrested. He admitted to marrying Clara for the money and planning to kill her next.

The telegram that saved her life came from Elizabeth Hardwick. She grew suspicious of Waite after seeing him dine with his mistress and finding out that her father, Waite’s employer and a doctor, was bluntly denied access to John Peck’s body by Waite.

8 The Homeopathic Killer

Back in the mid-19th century, Edmond de la Pommerais had a homeopathic practice in Paris. Despite being successful, Pommerais still found himself in debt due to his penchant for gambling. Like Arthur Warren Waite, he realized that the best way to solve his financial woes was to marry into money.

In 1861, he married Mademoiselle Dabizy. Even though she stood to inherit a fortune, her mother was still in charge of the money and she disapproved of her daughter’s marriage to Pommerais. Obviously, she had to go.

Just a few months after the wedding, Madame Dabizy went to her daughter’s house for dinner and fell violently ill. She died a few days later, and Pommerais, as her physician, ruled that Asiatic cholera was the cause of death.

With his wife’s inheritance, the homeopath was able to live the sweet life, at least for a short while. In 1863, Pommerais found himself in debt again. This time, he hatched a scheme with his mistress, Seraphine de Pauw, to commit insurance fraud.

The original plan involved de Pauw taking out an insurance policy with Pommerais as her benefactor. Afterward, she would be diagnosed as terminally ill by him and receive an annuity from the insurer. However, Pommerais decided it would be better if he gained the entire payout so de Pauw also fell mysteriously ill and died.

The plan almost worked, but Seraphine’s sister knew of the original scheme and went to the police. They recruited French forensic pioneer Ambroise Tardieu who tested de Pauw’s vomit and proved she had been poisoned with digitalis.[3] Pommerais was sent to the guillotine in 1864.

7 Murder By Mail

In the late 19th century, dowager Josephine Barnaby was one of the most prominent residents of Providence, Rhode Island. Eventually, the heiress trusted all her affairs to her confidante and physician, Thomas Thatcher Graves. With power of attorney, Graves managed to name himself as the benefactor of Mrs. Barnaby’s estate.

He could have waited for the woman to die and might have gotten away with it. However, Graves became impatient. Knowing that the dowager enjoyed a drink or two, he sent her a bottle of whiskey laced with arsenic from an anonymous admirer while she was visiting a friend in Denver.[4] Both Mrs. Barnaby and her friend drank the whiskey, fell ill, and died.

Graves thought that he had covered all his tracks. He had bought the bottle in Boston and asked a man at the train station named Joseph Breslyn to write the note so that Mrs. Barnaby wouldn’t recognize his handwriting. Therefore, when he was summoned to Denver to testify against another man, Graves found nothing suspicious.

However, it was all a ruse cooked up by famed Pinkerton James McParland to get Graves to Denver so McParland could arrest Graves. At the trial, the prosecution brought in Breslyn, who testified against the doctor. Graves was found guilty but committed suicide in his cell.

6 A Deadly Love Triangle

In 1959, Dr. Bernard Finch was a successful surgeon when 18-year-old Carole Tregoff became the new receptionist at the Los Angeles medical center where he worked. The two soon started an affair which eventually led to talks of marriage. There was just one problem—both of them were already married.

Tregoff had no qualms about divorcing her husband, but Finch’s situation was a bit trickier. If he divorced his wife, Barbara, she would be entitled to half of his considerable wealth and even more if she could prove that he had committed adultery. The simplest solution was to kill her.

If Finch planned his wife’s murder, then clearly he was not meant for a life of crime. He waited for Barbara to arrive home, walked up to her in the driveway, and, after a brief struggle, shot her point-blank. Afterward, he and Tregoff left Los Angeles individually. They reunited in Las Vegas where both were promptly arrested and charged with murder.[5]

There was plenty of forensic and circumstantial evidence as well as two witnesses who testified against Finch and Tregoff. However, Finch managed to convince some members of the jury that the gun belonged to Barbara and it had accidentally gone off while he was trying to pry it away from her.

The first two juries were deadlocked. In 1961, a third sentenced both Finch and Tregoff to life in prison. They served 10 and eight years, respectively, before being paroled.

5 The Richmond Poisoner

At first glance, it seemed that Isabella Smethurst’s death was a clear case of murder at the hands of her husband, Dr. Thomas Smethurst. However, a forensic mistake, accusations of bias during the trial, and public pressure ensured that the man dubbed “The Richmond Poisoner” walked away scot-free. He was even able to claim the inheritance which allegedly was his reason for murder.

In summer 1858, the Smethursts had moved to Richmond in London. Soon afterward, Mrs. Smethurst became ill. Her doctor immediately suspected poison and sent a sample of her vomit to Dr. Alfred Swaine Taylor for analysis. He found arsenic, and Dr. Smethurst was arrested. However, since he hadn’t been convicted yet, Smethurst convinced the magistrate to let him be with his ailing wife. She died the next day.

It emerged soon afterward that Thomas and Isabella were in a bigamous relationship. She also left him everything in a will signed “Isabella Bankes, spinster.”[6] Furthermore, Dr. Taylor announced that he had found arsenic in one of Smethurst’s bottles. It was mixed with another chemical to evade detection.

The case looked like the Victorian version of a slam dunk. However, Dr. Taylor, despite being dubbed the “father of British forensic medicine,” was not infallible. The arsenic found in Smethurst’s bottle actually came from the contaminated copper gauze that Taylor had used for testing.

Furthermore, the presiding judge, Sir Frederick Pollock, was accused of trying to sway the jury against the defendant. Although Smethurst was originally found guilty, public pressure convinced the Home Secretary to give him a reprieve and eventually a full pardon. He was still imprisoned for one year for bigamy.

4 Doctor By Day, Robber By Night

By all accounts, Dr. Levi Weil had a successful practice in 18th-century London. This makes it even more surprising that he organized a gang of Jewish criminals to commit robbery and murder.

The gang consisted of German and Dutch Jews lured to London by Weil with promises of easy scores. The robbery that ended their crime spree took place in late 1771 when the band targeted the farm of a widow named Mrs. Hutchings in King’s Road, Chelsea. Only Mrs. Hutchings and her two female servants were awake. So the mob forced their way in, tied them up, and proceeded to loot the house.

One apartment was occupied by two farmhands named John Slow and William Stone who were sleeping when they were assaulted by Weil’s crew. Slow was killed by a gunshot, while Stone was dazed by a blow from the doctor. He managed to recover and escaped through the window but died of his injuries the next day.[7]

Initially, the gang got away with the crime. Then one of their own turned on the others in exchange for immunity and a reward. The public was shocked to learn that the leader of the murderous gang was a man with a superior education who had earned his medical degree at Leiden University.

Six men were put on trial. Two were let go due to lack of evidence, but Weil and three accomplices were convicted and hanged.

3 Murderer Or Unlucky?

During World War I, Dr. Pierre Bougrat served his country and received the Military Cross and the Legion of Honor. Afterward, he set up a successful practice in Marseille where he sometimes offered free medical services to the downtrodden. He also enjoyed living lavishly and spending money, particularly on women. Consequently, this landed him in financial trouble on multiple occasions.

One day in 1925, Bougrat was treating a former brother-in-arms named Jacques Rumebe. Bougrat was injecting the man with salvarsan, an organoarsenic used back then to treat syphilis. Rumebe was a debt collector. He had come in with a large satchel of money, and that was the last time he was seen alive.

Initially, people assumed that Rumebe had run away with the money. However, a few months later, Bougrat was arrested for forging a check. While going through his office, police noticed a cupboard door that was covered by tapestry. Inside, they found the decomposing body of Rumebe.[8]

To most people, it appeared obvious that Bougrat had killed his patient and stolen the money. However, the doctor desperately tried to convince authorities that Rumebe committed suicide because he lost the money in a brothel.

Thinking that nobody would believe him, Bougrat hid the body in an act of desperation. Turns out he was right. Nobody believed him, and Bougrat was sent to a penal colony in French Guiana.

2 The Irish Bluebeard

Several doctors on this list had high standings in society due to their successful practices but none more so than Dr. Robert George Clements. He was a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in his hometown of Belfast. Therefore, when his wife (and wealthy heiress) Amy Burnett Clements died suddenly in 1947, many people considered it a tragedy. Others, however, noticed that she was Clements’s fourth wife to die under suspicious circumstances.

The wives had a few things in common: They all willed money to their husband, their bodies were cremated soon after death, and Clements either determined or “influenced” the official cause of death on their death certificates. Even in the last case, Dr. Clements strongly suggested a diagnosis of “myeloid leukemia” to his colleague in charge of the postmortem. Despite lingering doubts, the colleague reluctantly agreed.

However, four was too many and the police finally decided to investigate. Despite Clements’s protests, Amy Clements’s cremation was postponed and another postmortem was performed. This time, the cause of death was ruled morphine poisoning.[9]

Clements never went to trial as he was found dead in his lab with over 300 times the lethal dose of cyanide in his system. His suicide letter said that he could no longer tolerate the insults and accusations.

1 The Lambeth Poisoner

Dr. Thomas Neill Cream is primarily remembered today for his connections to Jack the Ripper. People who believe that the two were the same person point to Cream’s medical training, his targeting of prostitutes, and his alleged confession. While being hanged, he said, “I am Jack the . . . ”

Ripper aside, Cream created his own murderous path through England, the United States, and Canada.

Born in Scotland and raised in Canada, Cream opened his practice in Ontario. His first likely victim was his patient and alleged mistress, Kate Gardener, who was dumped in an alley in 1879, dead from chloroform poisoning. Her death could have been the result of Cream’s side business—giving abortions to prostitutes. To avoid prison, he moved to the United States and continued his back-alley abortions in Chicago.

Different sources ascribe a number of suspicious prostitute deaths to Cream during this period. However, it’s difficult to say if they were victims of willful murder or the inherent dangers involved in the illegal abortions of that time.

One person definitely murdered by the doctor was Daniel Stott.[10] Cream was supplying him with epilepsy medicine while also sleeping with his wife.

When Stott became a problem, Cream slipped some strychnine into his medicine. The doctor’s mistake was trying to pin the murder on the pharmacist. This caused an investigation to be launched into Stott’s death, for which Cream was convicted.

Years later, Cream was released and moved to London, settling in Lambeth. This is when his killing spree kicked into high gear as he began poisoning prostitutes for the fun of it. He killed four women.

But Cream couldn’t help himself and wrote letters trying to implicate other men in the murders. Even worse, he once met a US policeman and gave him a tour of Lambeth, describing the murders in such detail that it immediately raised the officer’s suspicions. So he reported it to Scotland Yard.

Read about more chilling murders in the medical community on 10 Serial-Killing Nurses and 10 Chilling Times When Patients Killed Their Doctors.