Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

15 Influential Early Works of Apocalyptic Fiction

Earlier this year, List Universe published a fine list of 10 great post-apocalyptic novels. The list below is along the same vein, but examines ONLY works published between 1805 and the start of the nuclear age in 1945. Quite possibly only three or four of these works will be familiar to anyone who is not an aficionado of this wide-ranging genre, though people may recognize many of the authors.

Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic literature involves any of the following: alien invasions, pandemics, severe natural disasters, the fall of civilization, the end of the world (“dying earth”) and massive wars. Most of the following works were influential to some degree, whether they influenced other authors or the wider genre in general. Most of these works can be found in most public libraries and at online literature sites such as Project Gutenberg.

PLEASE NOTE: This list goes in chronological order. Also, my cutoff date is technically July 1945, when the nuclear age began; therefore, novels such as 1949’s Earth Abides don’t belong on a pre-nuclear age list. So, please check publication dates before you say, “What about X, Y and Z?”

The Earth of the far future is dying, and men are sterile. The last few men are found in Brazil, where one of their number attempts a horrific experiment. Grainville’s novel is generally considered the first work of fiction in the “last man on earth” genre.

Despite a similar title to Grainville’s novel and a similar “last man” theme, Shelley’s The Last Man is quite different. She tells the tale of the last man to survive a plague in the late 21st century. Shelley based many of the characters on her contemporaries who had passed away; her protagonist, Lionel, is supposedly Shelley’s autobiographical image of herself. Critics verbally demolished the 3-volume novel when first published and it didn’t see daylight again until the 1960s. Nowadays The Last man is considered a true classic of the genre.

In After London, or, Wild England, an unstated cataclysm kills most people in England. In the first part, a historian looks back on the fall of civilization. The descriptions of things returning to nature are echoed in 1949’s “Earth Abides” by George Stewart, the current competing History Channel and National Geographic Channel programs “Life After People” (HC) and “Aftermath: Population Zero” (NGC), and Alan Weisman’s intriguing speculative work, The World Without Us. In the less popular part 2, Jeffries explores the return of feudalism in England.

This intriguing, politically motivated novel is classified many ways; it is sometimes considered apocalyptic because of the massive destruction in one scene. Donnelley was an agrarian populist, and his novel is a utopian/dystopian critique of the then-modern world. His farmer hero travels to New York and beholds many wonders, such as broadcast newspapers, illumination powered by the Northern Lights (figure that one out), transparent sidewalks, airships, etc. But the city of wonders hides dark secrets of massive oppression.

No “best-of…” science fiction list can fail to include at least one work by H.G. Wells, one of the most critical authors in Western civilization. Wells makes his first appearance on this list with The Time Machine. The tale is long-since familiar: A man in Victorian London builds a time machine and travels hundreds of thousands of years into the future, where he meets up with both the docile and the savage descendants of humanity. The Time Machine was twice translated to the big screen. (Because of its various components, The Time Machine fits into the genres of general sci-fi, time travel, apocalyptic and dying earth.)

People will most likely be more familiar with this seminal work than any other. Indeed, rare is the list of “great works” of apocalyptic literature (or alien attack or great sci-fi in general) that fails to mention this fantastic tale of alien invasion. It’s been retold on radio (which caused a panic in 1938), on the big screen and TV, and in numerous books. It’s been re-imagined in even more books and influenced such movies as Independence Day (which is really just a fancy retelling of War of the Worlds).

A highly praised novella (a type that’s longer than a short story but shorter than a novel), The Machine Stops should seem familiar to latter-day readers. Echoes of this gem can be found in The Matrix, the Internet, video-conferencing and more. Forster wrote about a post-apocalyptic humanity that lives underground and is fully connected to The Machine for all their needs. Unlike The Matrix, humans are fully aware of their situation and can freely leave, but are discouraged because of the toxic conditions on the surface. The Machine eventually becomes an object of worship. It’s a nice, early entry in the man-vs.- machine concept.

This horror fantasy novel is one of the first of the “dying earth” subgenre. Millions of years in the future, the sun has done dark and the descendants of humanity (“abhumans”) struggle to survive in massive pyramid redoubts against both the darkness and powers on the outside. The only natural light comes from Earth’s remaining volcanism. H.P Lovecraft described the novel as “one of the potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.”

Jack London was famous for his novels of the great north (The Call of the Wild, etc.). He also wrote this apocalyptic tale, which takes places in 2072, 60 years after the “scarlet plague” killed most everyone on earth. One of the survivors realizes that he needs to pass on humanity’s knowledge or it will be lost forever. Interesting note: Six years after London published his novel, a terrible plague did in fact grip the world. The Spanish flu killed at least 50 million people in 1918-1920 (some sources say as high as 100 million people, which would make the death toll more than both world wars combined).

This Czech play is famous for having introduced the world to the term “robots.” With a plot that would ring familiar to any Terminator or Battlestar Galactica fan, R.U.R. features robots who were initially created to serve humans but who rebel and destroy humanity instead. Fun fact: A 1938 BBC production of R.U.R. is credited with being the first-ever science fiction television program.

Our humanity (homo sapiens) is the first and most primitive of 19 subsequent human species on earth in Stapledon’s massive work. Many civilizations rise and fall throughout the 2 billion-year scope of the novel. Stapledon anticipated such things as genetic manipulation and nuclear holocaust in Last and First Men. He deeply influenced the works of many people, including C.S. Lewis, Brian Aldiss and Arthur C. Clark.

Wells’ final entry on my list pretty much accurately foretold the aerial destruction of cities in the next world war, and the eventual development of ballistic missiles launched from subs. Wells was mainly concerned with pushing his utopia of a secular, one-world government where science reigns supreme and dissenters are given the chance to kill themselves a la Socrates. Sci-fi aficionados might be more familiar with the 1933 movie version starring Raymond Massey, which diverts from the novel considerably (if not thematically); Wells himself wrote the screenplay.

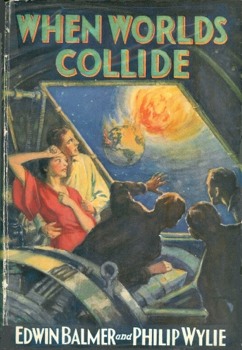

This intriguing tale and its sequel, After Worlds Collide (1934), had tremendous influence on sci-fi and fantasy. Echoes of When Worlds Collide can be seen in the comic strips Flash Gordon (started in 1934) and Superman (who first flew in 1938). Although the science in these two apocalyptic tales is sketchy, they’re still fun (if a bit turgid in places). The story: Two “rogue planets” are heading to our solar system. “Alpha” will cause much destruction when it passes near Earth before it swings around the sun to come back and annihilate the planet, while “Beta” will assume a stable orbit. A group builds spaceships to travel to Beta and escape the holocaust. The 1951 George Pal movie version, which changes some of the characters, is my favorite flick from the golden age of popcorn sci-fi. It’s supposed to be remade for the 2010 movie season.

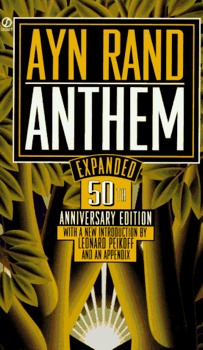

In many ways (though perhaps not intentionally), this novella is an answer to Wells’ Shape of Things to Come. The oppressive, centralized government is the villain here, which attempts to wipe out all individuality. (It’s a recurring theme of dystopian fiction.) In the story, Equality 7-2521 excels at math and science, but the government decrees that he will be a street sweeper. He escapes from the city through an old subway and discovers the world apart from the oppressive government. He and his love learn of the past thanks to a preserved library of books. Fascinating note: Rand once suggested to Walt Disney that he make a movie of Anthem, because animation could tell the story better than live action.

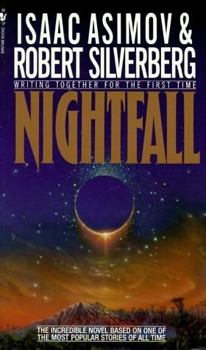

Nightfall is the only one of these works that doesn’t take place on (or near) Earth, but it’s definitely apocalyptic. Six stars continually illuminate a civilization far away. Scientists discover that every 2,049 years, the most visible sun is eclipsed, causing temporary darkness. But because the civilization only experiences light, past eclipses led immediate to the fall of civilization—which is, of course, what happens. A highly influential story (Asimov later expanded it to a novel with Robert Silverberg), Nightfall has been anthologized at least 48 times!

Notable Extras: By The Waters of Babylon, Zothique, Rescue Party, The Moon Maid