Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

10 Astounding Actions Earning A Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor is the highest military decoration awarded by the United States government. It is bestowed on a member of the United States armed forces who distinguishes himself “conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States.” Because of the nature of its criteria, the medal is often awarded posthumously.

In one of the most awe-inspiring displays of reckless bravery WWII has to offer the history books, Cmdr. Evans, three-fourths Cherokee from Oklahoma, led his destroyer, the USS Johnston, straight into the face of a gargantuan Japanese naval fleet, on 25 October 1944, off Samar Island, in the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

He was part of a very small fleet designed to support the marines currently assaulting Leyte. This fleet had 3 destroyers, very small ships, 4 destroyer escorts, even smaller, and 6 escort carriers, with only about 30 planes each. The fleet was not expecting a naval engagement because Adm. Halsey’s much larger fleet was supposed to be guarding the north flank. Halsey, however, had gone after another Japanese fleet and left the flank open.

Down came another Japanese fleet intent on destroying the marines on Leyte. Task Unit 77.4.3 (Taffy 3) initially tried to flee the area when confronted by such massive force. Evans, however, refused to yield to the enemy. As soon as the Johnston sighted the enemy, Evans came over the intercom, “A large Japanese fleet has been contacted. They are fifteen miles away and headed in our direction. They are believed to have four battleships, eight cruisers, and a number of destroyers. This will be a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival cannot be expected. We will do what damage we can.”

He ordered the Johnston to come about and attack at flank speed, charging the entire fleet alone. When Adm. Sprague, in charge of Taffy 3, saw this, he laughed and said, “Well, what the hell. You gotta die of something. Small boys attack.”

The rest of the destroyers and destroyer escorts turned and followed the Johnston, and the Japanese opened fire with 18.1 inch guns, 16 inch guns, 14 inch guns, 8 and 6 inch guns, blasting up the water on both sides of the Johnston. Astoundingly, Evans conned the ship through the splashes in a zigzag until he was within range with his 5 inch guns, which could not penetrate the hulls of the IJN’s battleships and cruisers. He ordered fire concentrated on the upper decks to do the most damage, and this succeeded in knocking down the superstructures and setting the ships afire.

Then the Johnston fired torpedoes and blew the bow off the Kumano, a heavy cruiser, which necessitated another cruiser leaving the fight to assist evacuation. Finally, the Japanese scored hits, a 14 incher, and three 6 inchers, which went clean through the entire vessel without detonating. The first knocked out half the engine power and the electricity to the aft gun turrets.

Evans was struck by one of the blasts and had 2 fingers ripped from his left hand and his shirt burned off.

The Johnston was crippled, but still refused to withdraw and set out a smoke screen. The other destroyers and escorts arrived and every man was consigned to death in order to enable the escort carriers to escape.

By the time it was over, the Johnston had slugged it out with titanic battleships and cruisers, and a line of 4 IJN destroyers, driving the latter off, until another salvo knocked the engine out and detonated several 5 inch shells in the forward magazine.

The Johnston was dead in the water and the IJN surrounded it and fired from all sides. Incredibly, Evans refused to order “abandon ship” until all remaining rounds had been fired, even the starbusts, which are like flares, and the sandbag rounds for practice. When the Japanese passed the survivors in the water, they threw them food and water and saluted them, shouting, “Samurai! Samurai!”

Evans was not among the survivors pulled from the water after the battle. His fate is unknown. He may have been eaten by sharks.

One of the more darkly humorous episodes of warfare occurred on 29 January 1945, in Holzheim, Belgium. Funk and his paratroopers were assaulting the town, and he left a rearguard of 4 men, while he scouted ahead to link up with other units, Those 4 men had to guard about 80 German prisoners.

Another German patrol of 10 happened by and overwhelmed the 4 Americans, freeing the prisoners and arming them. When Funk returned around the corner of a building, he was met by a German officer with an MP-40 in his stomach. The German shouted something at him, and Funk looked around.

There were now about 90 Germans, about half of them armed, and 5 Americans, disarmed except for Funk. The German shouted the same thing at him again, and Funk started laughing. He claimed later that he tried to stop laughing, but the fact that the German was shouting in German touched a nerve. Funk didn’t speak German. Neither did any of the other Americans. Why would the German officer expect him to understand?

His laughter and non-compliance caused some of the Germans to start laughing. Funk shrugged at them and started laughing so hard he had to bend over. He called to his men, “I don’t understand what he’s saying!” All the while, the German officer was shouting more and more angrily.

Then, quick as lightning, Funk swung his Thompson submachine gun up and emptied the entire clip into the German, 30 rounds of .45 ACP. Before the other Germans could react, he had yanked the clip out and slammed another in and opened fire on all of them, screaming to his men to pick up weapons. They did so, and proceeded to gun down 20 men. The rest dropped their weapons and put their hands up.

Then Funk started laughing again and said to his men, “That was the stupidest fucking thing I’ve ever seen!”

One of the hardest fights the Allies had in Europe was outside Aachen, Germany, the Battle of Crucifix Hill. The crucifix is still there, now a monument to the battle. Brown was placed in charge of Company C, with about 120 men, assigned to take the hill or die trying. The entire American force on the hill was a full regiment of about 500. They were facing an equal number of well entrenched Germans. If the hill was not taken, the Allies could not encircle Aachen. The Germans could pour down artillery on the entire town.

There were at least 43 pillboxes and bunkers, bristling with machine guns and plenty of men. Company C was assigned pillboxes 17, 18, 19, 20, 26, 29, and 30. The worst of these was 20, with a 360 degree turret on top armed with an 88 mm cannon. The walls were 6 feet of steel reinforced concrete.

After crawling 150 yards under heavy enemy fire to 18 and blowing it up with a satchel charge, Brown crawled again through heavy enemy fire, 35 yards to 19, and several mortar rounds landed around him, knocking him down. He got back up, climbed on top of the bunker and dropped a bangalore torpedo through a hole in the roof. This blew a larger hole, into which he dropped a satchel, and destroyed the emplacement.

20, however, had 45 men and 6 machine guns aimed out around it. When he returned for more demolition, his sergeant told him, “There’s bullet holes in your canteen.” He had been hit in the hip and was bleeding profusely. He crawled down a communications trench 20 yards from 19 to 20, and saw a German entering a steel door in the side. Brown was an ex-boxer, and knocked this man out with one swing, through him inside, and then threw 2 in satchel charges, and ran.

20 exploded so violently that flames flew out the top and caught a tree on fire. Brown personally led his men on a path of destruction through the rest of their assignments, and after an hour of tooth-and-nail fighting, Crucifix Hill was reduced to smoking rubble.

Brown shot himself in 1971, plagued ever since the war with bad memories and pain from his wounds.

On 2 May 1968, 12 Green Berets were surrounded near Loc Ninh, South Vietnam, by an entire battalion of NVA. They were thus outnumbered, 12 men versus about 1,000. They dug in and tried to hold them off, but were not going to last long. Benavidez heard their distress call over a radio in town and boarded a rescue helicopter with first aid equipment. He did not have time to grab a weapon before the helicopter left, so he voluntarily jumped into the hot LZ armed only with his knife.

He sprinted across 75 meters of open terrain through withering small arms and machine gun fire to reach the pinned down MACV-SOG team. By the time he reached them, he had been shot 4 times, twice in the right leg, once through both cheeks, which knocked out four molars, and a glancing shot off his head.

He ignored these wounds and began administering first aid. The rescue chopper left as it was not designed to extract men. An extraction chopper was sent for, and Benavidez took command of the men by directing their fire around the edges of the clearing in order to facilitate the chopper’s landing. When the aircraft arrived, he supervised the loading of the wounded on board, while throwing smoke canisters to direct the chopper’s exact landing. He was wounded severely and at all times under heavy enemy crossfire, but still carried and dragged half of the wounded men to the chopper.

He then ran alongside the landing skids providing protective fire into the trees as the chopper moved across the LZ collecting the wounded. The enemy fire got worse, and Benavidez was hit solidly in the left shoulder. He got back up and ran to the platoon leader, dead in the open, and retrieved classified documents. He was shot in the abdomen, and a grenade detonated nearby peppering his back with shrapnel.

The chopper pilot was mortally wounded then, and his chopper crashed. Benavidez was in extremely critical condition, and still refused to fall. He ran to the wreckage and got the wounded out of the aircraft, and arranged them into a defensive perimeter to wait for the next chopper. The enemy automatic rifle fire and grenades only intensified, and Benavidez ran and crawled around the perimeter giving out water and ammunition.

The NVA was building up to wipe them out, and Benavidez called in tactical air strikes with a squawk box and threw smoke to direct the fire of arriving gunships. Just before the extraction chopper landed, he was shot again in the left thigh while giving first aid to a wounded man. He still managed to get to his feet and carry some of the men to the chopped, directing the others, when an NVA soldier rushed from the woods and clubbed him over the head with an AK-47. This caused a skull fracture and a deep gash to his left upper arm, and yet he still got back up and decapitated the soldier with one swing of his knife, severing the spine and all tissue on one side of the neck. He then resumed carrying the wounded to the chopper and returning for others, and was shot twice more in the lower back. He shot two more NVA soldiers trying to board the chopper, then made one last trip around the LZ to be sure all documents were retrieved, and finally boarded the chopper. He had lost 2 quarts of blood. Before he blacked out, he shouted to one of the other Green Berets, “Another great day to be in South Vietnam!”

This battle lasted six hours. He had been wounded 37 times.

The first Medal of Honor recipient for actions during the battle of Iwo Jima, Stein charged right into the thickest parts of the fray on D-Day, with the 1st Battalion, 28th Reg., 5th Marines Div. in the assault across the narrowest part of the island, in order to cut off Mount Suribachi from the rest.

He was armed with a homemade .50 caliber machine gun that he salvaged from a downed American aircraft on another island. He fired this from the hip as he charged across the volcanic plains, and engaged the enemy at every pillbox and bunker that he saw shooting at him.

He was observed far ahead of the rest of his men, following, not fleeing, the dust-spots of machine gun fire all around him, disappearing and reappearing in mortar explosions, sprinting and firing at them face to face.

He deliberately stood upright from cover to draw enemy fire to him and away from pinned down marines, and to ascertain enemy locations, then charged them and killed 20 enemy soldiers before he ran out of ammunition. His weapon fired 100 rounds in 5 seconds.

He took off his helmet and boots, then ran back down to the beach to rearm, then returned and resumed fighting. He did this 8 times, and on every trip back to the beach, he picked up a wounded man and carried him on his shoulders. He destroyed at least 14 enemy installations on the first day of action.

He was killed almost 2 weeks later on a scouting mission, by a sniper, after having been given leave from the island, and then returning when he heard how hard a time his buddies were having.

When told about Stein afterward, Joe Rosenthal, who took the famous flag-raising picture on Suribachi, said, “Running through bullets and not getting hit is like running through rain and not getting wet!”

Thomas Baker personally shot 12 Japanese soldiers manning a machine gun behind his lines on Saipan. This was several days after he ran ahead of his men into the open fire of a pillbox, and fired a bazooka into it. Right after he killed those 12 men, he ran farther back to occupy a rearguard position for his men as they advanced across open terrain. He surprised a group of 6 enemy soldiers concealed and waiting to ambush the next group of Americans to pass. He shot all 6 dead.

Almost 3 weeks later, as the Battle of Saipan was drawing to an end, the Japanese staged a last-ditch banzai attack, the largest of the war, at night, and Baker’s perimeter was beset on 3 sides by at least 3,000 drunken, screaming soldiers. There may have been 5,000.

He dug into a foxhole and shot down scores of them until his ammunition was exhausted, by which time he had been shot in the abdomen. He then destroyed his rifle by using it as a baseball bat against a dozen more.

Another marine ran to rescue him and carry him back. He had gotten about 50 yards when a Japanese soldier shot the rescuer dead. Baker shot the Japanese dead with the rescuer’s rifle. A second marine arrived to help him, but Baker shoved him away, shouting, “Get away from me! I’ve caused enough problems! Gimme your .45!”

The marine handed it to him and propped him against a tree and fled. A third marine passed some time later and offered to help him, but Baker refused. When they found him the next morning, he lay dead against the tree in a pool of blood, his pistol empty, and 8 dead Japanese soldiers around him.

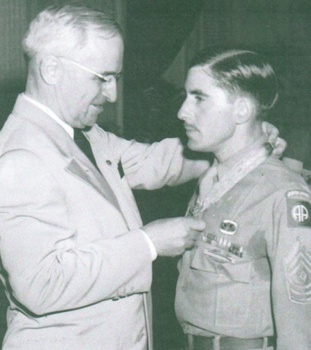

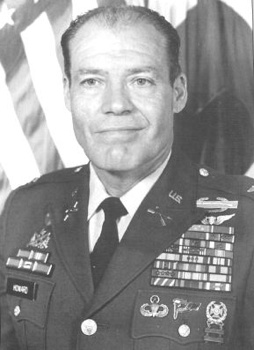

S/Sg Bob Howard is the closest anyone has ever gotten to 3 Medals of Honor for 3 separate actions. He was a Green Beret of the highly classified Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG), and his men engaged in black ops all over North Vietnam, and into Cambodia at a time when these actions were very sensitive to world opinion of the United States.

This is why his first two actions were downgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross: the government did not want to draw attention to the MACV-SOG. His Medal of Honor finally came because of a rescue mission he led into Cambodia to find Pfc. Robert Scherdin. Howard was a Sfc. at the time, and after his platoon left the cover of its helicopter, it was attacked by 2 companies of NVA, about 300 men.

Howard took shrapnel to the fronts of his legs and forearms from a grenade, and his rifle was blown to pieces out of his hands. When he sat up he saw his platoon leader seriously wounded and exposed to fire, and proceeded to crawl through withering machine gun and small arms fire. As he administered first aid, a bullet blew one of his ammunition pouches off his belt, detonating several magazines of M-16 rounds.

He still crawled back with the wounded platoon leader, then crawled among his buddies administering first aid, and directing their fire to better places. This lasted for 3 and a half hours, until they actually fought the NVA off and permitted the arrival of two more helicopters. Howard refused to leave until everyone was aboard, all the while taking heavy enemy fire from within the jungle.

Howard was wounded 14 times in 54 months performing deeds like this. He died 23 Dec. 2009 in Waco, TX, from pancreatic cancer.

WWI’s most famous American hero could not stand talking about what he did to become so. He was a conscientious objector, claiming Christianity on his draft notice, and yet was still drafted because the U. S. military does not put much stock into Christian pacifism (though Jesus was quite clear on whether or not you should kill people).

He finally decided to go to war because he would be helping stop the Germans and save American lives. He became well known as the finest marksman at Camp Gordon, GA, scoring perfect bullseyes with open sights more often than the snipers did with scopes.

When his drill instructor how he did it, he said something one might expect from Yogi Berra, “I was born shootin’ a gun better than I could read, sir. I still can.”

York’s battalion was sent to secure the Decauville railway, just north of Chatel-Chehery, in North France, just south of Belgium, on 8 October 1918. 17 men, four non-coms, and 13 privates were ordered to flank the German line and destroy the machine guns from the rear. They captured about 70 Germans and were trying to disarm them, when the machine guns spotted them and turned around to fire on them. 9 Americans around York dropped immediately, 6 of them dead.

Corporal York was now in charge, and left the 7 Americans still fit for duty to guard the Germans while he ran from cover to cover up the hill, shooting the whole way.

“And those machine guns were spitting fire and cutting down the undergrowth all around me something awful. And the Germans were yelling orders. You never heard such a racket in all of your life. I didn’t have time to dodge behind a tree or dive into the brush… As soon as the machine guns opened fire on me, I began to exchange shots with them. There were over thirty of them in continuous action, and all I could do was touch the Germans off just as fast as I could. I was sharp shooting… All the time I kept yelling at them to come down. I didn’t want to kill any more than I had to. But it was they or I. And I was giving them the best I had.”

He shot 15 men dead with his own rifle, and was out of ammunition. He then pulled his .45 and shot 8 more that charged him with bayonets. He then grabbed one of their rifles and fired on a few more machine gun nests, until the Germans surrendered.

When a friend back home, who did not enlist, asked him how many Germans he killed, York started sobbing so hard he threw up. He had killed at least 28.

WWII’s answer to SG York was a man only 5 feet 5 inches tall, and 150 pounds. He earned every major combat award the U. S. has to offer, fighting in Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, Rome, and France. He got the DSC in Normandy, when a German called down from a hilltop that he was surrendering. One of Murphy’s buddies took the bait and stood up, right into a sniper’s bullet. This infuriated Murphy, who jumped up and shot the sniper dead, then charged up the hill and wiped out a machine gun nest of 6 men, firing and throwing grenades at them. Then he picked up the MG-42 and charged over the hillside spraying it from the hip, killing 10 more men.

When asked how it felt to have the DSC, he said, “I got the DSC. All he got was dead.” It was on 26 January 1945, in Holtzwihr, France, almost on the German border, that he earned the Medal of Honor for ordering his men to retreat as the German assault on the town began. His unit had only 19 fighting men left out of 128. He stayed behind and shot the Germans as they emerged from the woods to cross a clearing, until he was out of ammunition. He then climbed onto a burning tank destroyer and used the .50 caliber machine gun to push them back. The Panzers and mortars started blowing up the ground all around him, but he continued this one-man assault for an hour, until he started calling in artillery strikes over the tank destroyer’s phone.

He called these strikes in closer and closer to his position, blowing up Germans and tanks less than 50 yards from him. He finally called a strike on his position, prompting the man on the other end to say, “That’s right on top of you! How close are they!?”

“Hold the phone! I’ll let you talk to them!” he shouted and jumped from the vehicle, and ran into the woods as they overran his position and were struck down again by American cannon fire. As the Germans were in disarray, he called his men out and organized a counter-attack, driving the German’s back.

His men estimated that he had killed 50 men.

William Hawkins waged one of the most furious one-man army assaults on enemy positions in the history of modern warfare. When the marines went ashore on Tarawa atoll, Betio Island, Hawkins told Robert Sherrod, who later became an editor for the Saturday Evening Post, that he would put his platoon of 40 men against any company of 150 men on Earth and guarantee to win.

“He was slightly wounded by shrapnel as he came ashore in the first wave, but the furthest thing from his mind was to be evacuated. He led his platoon into the forest of coconut palms. During a day and a half he personally cleaned out six Jap machine gun nests, sometimes standing on top of a track and firing point blank at four or five men who fired back at him from behind blockhouses. Lieutenant Hawkins was wounded a second time, but he still refused to retire.”

These machine gun nests were pyramidal huts about the size of a large trash can, made of 6 inch-thick steel, up into which a Japanese soldier could pop from underground and man the heavy or light machine gun through a 4 inch slit.

They were everywhere on the island, and the preparatory bombardment had missed most of them. While most of the marines dug in and kept their heads down, Hawkins stood up in full view not more than 5 yards from these pillboxes and fired his M-1 Carbine at them, killing the soldier and allowing his men to move forward to the next one. He refused to keep his head down, and when he ran out of ammunition, he ran up to their mouths and threw in grenades and satchel charges.

These machine guns fired explosive rounds, about .30 caliber, when a simple lump of lead isn’t enough. He destroyed 7 pillboxes and one blockhouse by himself, despite being wounded early in the engagement. The first was shrapnel as he disembarked the long Betio pier. Later in the day, one of the pillboxes caught him in the chest.

He was helped back to a medic, who bandaged him and demanded he get on a first aid boat and leave. He refused, and said, “Don’t tie it so tight that I can’t shoot.” The medic radioed Col. David Shoup, who also won the Medal of Honor for his leadership on the island, and Shoup asked Hawkins to leave.

“I’m not doing it, sir! I came here to kill Japs, not go home!”

Shoup relented and the medic complied, and Hawkins destroyed three more pillboxes by the end of the day. He was throwing his fourth grenade at another one when the gunner inside shot him dead. He was 29. Sherrod said later, “To say that his conduct was worthy of the highest traditions of the Marine Corps is like saying the Empire State Building is moderately high.”