Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Top 10 Greatest Art Crimes

When most people think of art crime, the first few images that come to mind are Pierce Brosnan’s suave smirk in The Thomas Crown Affair, or perhaps the comedic hijinks of Peter O’Toole and Audrey Hepburn in How to Steal a Million. Certainly, in this light, art crime appears seductive and amusing. As a lover of art heist films, I don’t blame anyone for this idealized generalization. But what are the real offences that haunt art world insiders? What are the bad deeds that induce headaches among art professionals and patrons alike?

Below are listed ten forms of art crime, in no particular order (unless you count saving the most scandalous for last). Many of the categories overlap – for example, art forgery is a type of fraud – but each details a certain genre of criminal phenomena, some much more serious and widespread than others. The art market is a massive moneymaking industry, but also one of the least standardized and policed. And now, the darker side of art…

Though visual artists have taken inspiration from their creative predecessors since time immemorial, sometimes re-imagining cultural imagery proves too close for comfort for the original author. Some argue that quoting another’s work borders on plagiarism, and violates copyright law; others contend that such references are merely free-speech commentary in the form of parody or homage. Appropriation allegations have plagued pop artists to postmodernists alike, with pesky court cases on the rise due to contemporary art’s preoccupation with depicting pop culture icons, with incorporating mass-produced commodities, and with challenging the concepts of originality and authenticity.

Many a well-known artist – from Andy Warhol to Shepard Fairey to Jeff Koons – has faced such lawsuits, with varying degrees of success. Not all battles are fought in the courts, however. Self-proclaimed “richest artist alive today”, Damien Hirst has been hounded for years by accusations of appropriating ideas, and not all cases have gone to trial. Though some critics have tried to slaughter him in the court of public opinion, Hirst has countered: “Lucky for me, when I went to art school we were a generation where we didn’t have any shame about stealing other people’s ideas. You call it a tribute.” Duly noted.

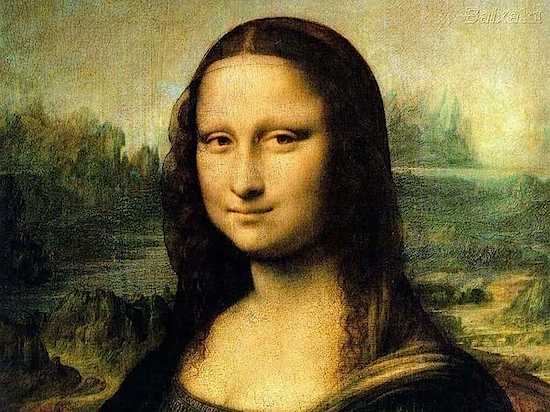

As a fan of (good) graffiti, I won’t be knocking that subset of art here; instead, I’m using the term vandalism to refer to any malicious damage done to works of art in a museum or gallery setting. While rare, vandalism has caused harm to some of art’s most iconic artworks: da Vinci’s famed Mona Lisa has been attacked at least four times, besieged by acid, by rock, by red paint and – I kid you not – by teacup. Rembrandt’s The Night Watch has been slashed with a knife on two occasions (the details of the first being sketchy), and doused with acid on a third; the painting was restored after each incident. Sometimes acts of vandalism have bizarrely sanctimonious motives, such as when Tony Shafrazi spray-painted the message “Kill Lies All” onto Picasso’s Guernica, supposedly as part political protest, part art historical upgrade. Similarly, Alexander Brener argued that his painting of a green dollar sign on Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematisme served as a “dialogue” with the deceased artist.

Perhaps the weirdest case of art sabotage involves so-called “serial art vandal” Hans-Joachim Bohlmann (1937-2009). For a whopping 29 years, Bohlmann intentionally defaced over 50 paintings at public exhibitions. With sulfuric acid as his weapon of choice, and images of faces his target, Bohlmann completely destroyed a Paul Klee artwork, and maimed others by Rembrandt, Rubens and Dürer. The total damage of his criminal career has been estimated to be around 270 million Deutsche Marks, or approximately $180.3 million (in 2010 US dollars). Diagnosed as suffering from a personality disorder, Bohlmann’s various treatments included electric shock, antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs, tranquilizers, a lobotomy and, ironically, art therapy. He eventually died of cancer.

While not technically a crime, per se, misguided or neglectful object care will cause art restorers, conservators, curators, appraisers and aficionados to bristle in revulsion. Over-cleaning a painting, refinishing an antique desk, exposing an object to too much humidity or an improper temperature: these mistakes can have dire consequences for the appearance and value of an artwork. The issue is muddled, however, by contradictory expert opinions on proper object care, as well as on the state of art conservation today. One camp argues that modern technological and research advances allow us to be more truthful to the artist’s original intentions and style, and that restorers are more careful in their techniques than their predecessors. Opponents retort that works of art are inappropriately handled and treated on a daily basis; as art professor and restorer Mauro Pelliccioli stated back in the 1960s, “Today more art is destroyed than is rescued by restoration. There has been no epoch so dangerous, so catastrophic for painting, as that through which we are passing.”

Bungled conservation practices can, themselves, draw a hefty museum crowd, as seen in the London National Gallery’s 2010 exhibition “Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries.” One of the show’s highlights, Woman at a Window (ca. 1510-30), was revealed, during a 1978 restoration, to have been originally a far…ahem…bustier portrait than assumed. The theory is that nineteenth-century restorers made a few “tasteful” alterations to make the lady more modest and fitting to the decorum of the times; luckily the later specialists were able to easily remove the added layer of paint.

The trafficking of art objects refers to the movement and exchange of works. As theft and looting are covered below, here I’ll focus on the transportation and selling of goods after the art has been plundered or stolen. In the Western “market” countries, buyers purchase stolen art – wittingly or unwittingly – from source countries, a practice that until recent decades was almost entirely unregulated. Some statements concerning such trafficking are downright terrifying: art journalist Godfrey Barker has previously claimed that “the illegal trade is 3,000 to 4,000 years old, if not actually older,” and guessed that approximately 98% of antiquities are stolen. While the accuracy of this estimate is unknown, it certainly paints a bleak picture of the world market for cultural artifacts.

Perhaps more frightening are the esteemed reputations of some of the purported culprits; the network of guilty parties can include everyone from museum staff and senior-level curators, to dealers and big-name collectors. Even members of mega auction houses have been accused, including employees of Sotheby’s and Paris’ Hôtel Drouot, where allegations of a trafficking ring led to twelve arrests in December, 2009. Accused art traffickers have consisted of various antiquity dealers, a former president of the National Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art and a Getty Museum curator.

Ever since art carried demand, people have been passing off works as the production of others. Though one might assume that modern technology and analysis tools would have rendered forgery attempts moot, this is far from the case; oftentimes, such dating and authentication methods are unavailable to potential buyers or dealers, or, conversely, various experts are able to sum up enough evidence to argue both sides, convincingly. In 1996, art historian Thomas Hoving estimated that forged art comprised up to 40% of the art market.

Dalí, Picasso, Matisse and Klee are favored prey, due to the intense popularity of their artworks, and their prolific output. Interestingly, not all forgers strive to wholly mimic a style without fault; they intentionally incorporate anachronisms, hidden messages or flaws that may protect them against future claims of forgery.

Some exposed forgers have been able to profit from their infamy and skill. Several years after being caught, art faker extraordinaire, Thomas Keating – who had claimed to have produced over 2,000 counterfeit paintings in the styles of more than 100 different artists – served as a presenter on British television programs detailing the techniques of old masters. Forgers have been known to earn enough notoriety that their fakes become high-priced collectibles on their own merit. In an amusing twist, art by renowned Vermeer forger Han van Meegeren became so celebrated after his death that his own son produced fakes in his father’s name. These were literally forgeries of forgeries.

Are you intrigued by art forgeries and interested in further investigation? Simply visit the Museum of Art Fakes in Vienna, Austria, an institution that provides proof positive of the mass appeal of faked masterpieces.

In an industry with (very) poor regulation, and with deals that are often struck on the flimsy basis of personal trust and a sturdy handshake, it is astonishingly easy to get away with slimy scams for years, if not decades. Former New York City gallerist Larry Salander was recently sentenced to a 6 to 18 year prison term for defrauding clients, artists and investors. Believed to total somewhere around $120 million in cost, his tactics included selling unauthorized works, neglecting to inform consigners when a sale had taken place, providing false information to secure loans and retaining payments instead of transmitting them.

Other fraud schemes in the news have included the case of a former Brooklyn Museum payroll manager who embezzled $620,000 by writing phony paychecks and wiring the money directly into his bank account, and that of a head of facilities at Winterthur Museum who spent $128,000 on a company credit card to finance personal purchases of flat screen televisions, computers, a digital camera and ATVs.

Investment fraud has made its way into the auction scene as well, with the personal valuables of Ponzi scheme con man Bernie Madoff, and the art collections of shamed financiers Halsey Minor and Marc Dreier, divvied up by auctioneers or planned for upcoming auctions. With auction houses aggressively competing to showcase these scammers’ ill-gotten spoils, it begs the question of the ethics surrounding the buying of goods that perhaps were purchased with the capital of fraud victims.

At last we come to art heist, the most glamorized form of art crime! It’s also one that is very much prevalent in today’s news articles and blogs, with recent thefts occurring at the Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Museum in Cairo (with Van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers being the art-napping victim), the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (paintings by Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Modigliani and Léger taken), and posh private residences such as supermodel Kate Moss’ North London home (three works of art were nabbed, including a Banksy portrait). Art theft from museums, galleries or private collections is not exactly as difficult as Hollywood films make it appear; in fact, such burglaries are often decidedly un-sexy, as crooks easily bypass flawed or nonexistent security systems, or simply schedule the attack during the less-secure, more chaotic periods of time between changing exhibits. Sadly, thieves often do considerable damage to a work of art during the theft, often cutting a painting from a frame or rolling a canvas with delicate paint chips.

It’s an uncomfortable reality that not too much has changed since the worst art heist of the 20th century: the theft, in 1990, of thirteen artworks (including paintings by Degas, Rembrandt, Manet and, the most valuable missing painting today, a $200 million Vermeer) from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The thieves, dressed as police officers, simply knocked on the door of the museum and were able to dupe the few security guards on duty long enough to gain entry.

A remarkable fact regarding the 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa is that Pablo Picasso himself was briefly questioned in connection with the missing painting. Scholar Silvia Loreti even alleges, in her essay “The Affair of the Statuettes Re-Examined”, that Picasso likely orchestrated the theft of Iberian statue heads from the Louvre, which were used as inspiration for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907).

Here, I am referring to the large-scale devastation of cultural centers and artifacts for political, religious and/or wartime purposes; looting, which I would argue involves preserving the art to profit from its value, is discussed below. Whether a willful act of an opposing party or the accidental collateral damage of a wayward smart bomb, the demolition of historical monuments, archaeological sites and art institutions is an egregious act that can be felt internationally, not solely in the country owning the affected land. Iconoclasm has a strong presence in the religious histories of the Byzantines, Muslims and Protestant reformers, and was also used for political or revolutionary purposes in ancient Egypt, ancient Rome and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. These are only a handful of innumerable cases.

Unfortunately, mass destruction of art continues to be a very big problem. Art obliterated in the 9/11 attacks included a Louise Nevelson sculpture, a Joan Miró tapestry, a Roy Lichtenstein painting and over 300 works by Auguste Rodin. During the war in Iraq, the American military razed sections of the historical site of Babylon to make room for parking lots, and an insurgent bomb damaged the top floor of the minaret of the Great Mosque of Samarra (once the world’s largest mosque).

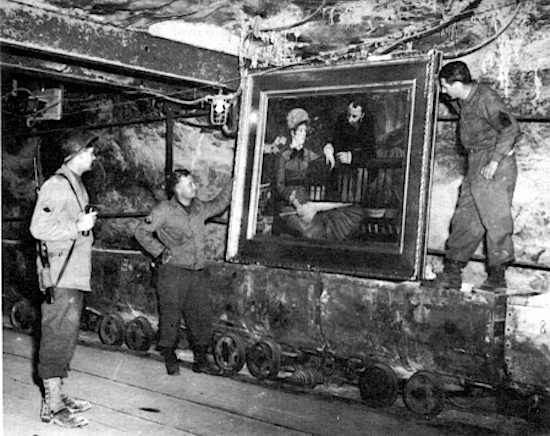

You can find images memorializing post-war pillaging throughout history, with the conquerors shown carrying the spoils of Persia, Jerusalem, or whatever ransacked realm, on their backs in victory marches. These acts aren’t isolated in the past, however; officials are constantly announcing new repatriation negotiations for artwork looted in the pandemonium of World War II, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In Noah Charney’s Art & Crime: Exploring the Dark Side of the Art World (2009), the author states that up to 75% of all art crime is in the form of looting and the antiquities trade, which prove profitable in part because, unlike more famous stolen artworks, they can be sold on the open market at their full value. War booty may not always be trafficked to collectors, however, but instead kept as personal souvenirs, as in the case of an Allied veteran who swiped – and later returned – a valuable book he found in Hitler’s Bavarian Alps home.

On a more uplifting note, there are moments in history in which the sense of fear and horror propagated by wartime motivated some of the most inspiring acts of courage. During WWII, individuals known as the “Monuments Men” rallied their efforts to hide and protect the cultural artifacts of Europe from Nazi plundering, and safeguarded the objects in repositories housed in salt mines, castles, villas and even a jail cell. In some cases, administrative staff had very short windows of opportunity in which to catalogue, pack and transport entire museum collections to secret locations. To hear more about the incredible pains civilians and officials took to shelter art, I highly recommend the documentary, The Rape of Europa (2007).

If you’ve read items 10-2 on this list, it’s quite clear that art has the mysterious power to elicit a wide range of criminal behavior. As art is created, traded, collected and admired by human beings – inherently passionate and fallible creatures – this fact is not terribly surprising. What is a bit startling, however, is the realization that some of art history’s masterminds have been victims, or villains, in some rather horrific personal crimes. Pointing this out is not meant to be particularly insightful about the nature of artists, but rather a simple case of revealing lesser-known tidbits to satisfy any sadistic curiosity about our creative icons.

Many have heard that Caravaggio, who harbored a particularly cantankerous personality, killed a man in a fight and remained a fugitive until his death. Many more may personally recall the attempted murder of Andy Warhol by Valeria Solanas (above), who shot him in his Factory studio, in 1968. Other readers may have forgotten that in the 1980s, minimalist great Carl Andre was tried for the second-degree murder of his wife, Ana Mendieta, who fell 34 floors to her death. While Andre was eventually acquitted, many were suspicious of the circumstances surrounding the fall (was it suicide? an accident? was she pushed?). The most contentious accusation against an artist, and one largely dismissed by art world insiders, involved crime writer Patricia Cornwell’s 2003 publication arguing that English Impressionist Walter Sickert had been a famous serial killer. Which serial killer was he, you ask? None other than Jack the Ripper.

For today’s aspiring artist or art professional, the industry’s notorious pretentiousness, close-minded sense of insulation, and elitist attitudes can seem like overwhelmingly daunting obstacles. When confronted with old-school art world snobbery, one might forget that art should be about creativity, education, discovery and encouragement. Ignore the snarky put-downs and the judgmental stares, however, and take heart: there are far more community-minded, positive cultural centers out there than you might think. Non-traditional art spaces are on the rise – some featuring a bookstore section, small gallery, residency studios, mini shop, etc. – and, in my experience, these places sometimes better serve the community as gathering places for relaxation, learning, interaction and innovation.