Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Books

Books 10 Famous Writers Who Were Hypocritical

Humans

Humans 10 of the World’s Toughest Puzzles Solved in Record Time

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

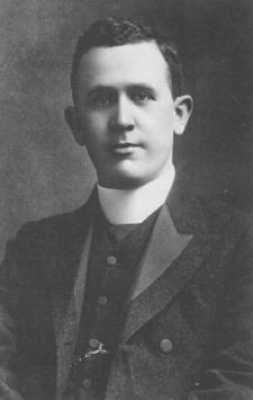

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Books

Books 10 Famous Writers Who Were Hypocritical

Humans

Humans 10 of the World’s Toughest Puzzles Solved in Record Time

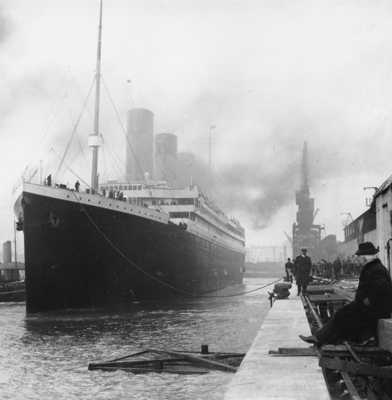

10 People Who Did Not Board the Titanic

I am writing this list on the 70th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, which launched the United States into World War II. In a few short months, we will reach another major anniversary – 100 years since the sinking of the Titanic. As everyone knows, the Titanic was the largest and most luxurious ocean liner of its time, and so technologically advanced that it was claimed the ship could not sink. Many wealthy and famous people were on board the Titanic for her maiden voyage from Europe to America in April 1912, including Benjamin Guggenheim and John Jacob Aster. Hundreds more every day people were also on board. Only 710 people would survive when the Titanic hit an iceberg in the icy waters of the North Atlantic and sank.

While 2,224 people set sail on the Titanic, many more were scheduled to make the voyage, but for one reason or another, never did. The reasons were as varied as the people who were on board. Though the builders of the Titanic spared no expense on accommodations, still, several people canceled their Titanic passages when they discovered their cabins to be unsatisfactory. For example, Colonel J. Warren Hitchens, and Mr. and Mrs. J. Clifford Wilson and their daughters Dorothy and Edith canceled their Titanic bookings, and sailed aboard Rotterdam instead. Others were delayed due to illness or changes in business plans. Still others decided to leave for America early, and canceled their reservations on the Titanic and booked passage on another liner.

Soon after the Titanic sank, reports came in from all over the world of those who claimed to have been scheduled to sail on the Titanic but who did not. They became known as the “Just Missed It” club. Many were obviously people seeking to gain notoriety, at the time, from the tragic event. But, the fact does remain that there were a number of people who, for one reason or another had actually received tickets or confirmed their passage and did cancel their trips. Several of these people claimed they canceled their tickets for sailing to America aboard the Titanic because they had premonitions of a disaster. Here are ten people who did not embark for America aboard the Titanic, and lived to tell the tale.

The United States ambassador to France, Mr. Robert Bacon, had reserved passage aboard Titanic for himself, his wife and daughter. But their departure was delayed by the tardy arrival of the new ambassador, Myron T. Hendrick. The Bacon family sailed April 20, on the maiden voyage of the S.S. France – instead of the ill-fated maiden voyage of the Titanic.

A toss of a coin was all that separated three men from being aboard the Titanic. In 1912, three worldly and wealthy male friends were taking a tour of the world. The three were Baron M. von Bethmann of Frankfort-on-the-Main, P. de La Vielestreaux, and Maurice Brevard of Paris. They eventually made their way to Chicago to visit commercial industrial and financial centers. While there they reported their near-miss with the Titanic.

“We intended coming over on the Titanic,” the Baron said, “mostly for the novelty of its maiden trip, but at the last moment concluded to take an earlier boat.” “Two of us wanted to wait on the new Titanic,” the baron said, “and the third felt that we would be wasting too much time. We tossed a coin to decide the matter and it fell in favor of an immediate start.”

Norman Craig was a Scottish MP and King’s Counsel, and had originally booked passage aboard the Titanic for her maiden voyage to America. He had decided to make the trip “for a blow of fresh air.” After the Titanic sank, some assumed he had been aboard or transferred to another ship for safe passage, but he never made the trip. He said “I suddenly decided not to sail, I cannot tell you why; there was simply no reason for it.” “I had no mysterious premonitions or visions of any kind nor did I dream of any disaster.” “But I do know that, at practically the last moment, I did not want to go.”

The Reverend James M. Gray was a pastor in the Reformed Episcopal Church, a Bible scholar, editor and hymn writer, and the president of Moody Bible Institute. It was in his capacity as Dean of Moody Bible Institute that fate intervened and probably saved his life. Reverend Gray was scheduled to preach at the graduating class ceremony of the institute and was about to head from England back to America, to do so. However, a friend, Reverend Harold, urged him to remain in England and return to America instead aboard the Titanic on her maiden voyage. Gray refused because he felt duty bound to be at the institute to preach to the graduates. He took an earlier steamship to America a week before the Titanic sank.

Edgar Selwyn was an important figure in American theater in the first half of the 20th century. He directed and produced films, but is probably best remembered for having co-founded and built the Selwyn Theater (now the American Airlines Theater) on Broadway, in 1918. However, had it not been for Edgar Selwyn’s desire to hear an early rendition of a new novel, he might have died aboard the Titanic and never built the theater.

English novelist Arnold Bennett recorded in his diary that a meeting between himself and the Selwyn’s was the only thing that saved their lives. The Selwyn’s came to see Bennett on April 19th, to hear him recite passages from his latest comic novel, and to do so forced them to cancel their plans to board the Titanic on April 10, 1912. They had planned on traveling aboard the Titanic with Mr. and Mrs. H.B. Harris, who did make the journey. It is possible their wish to get an early look at Bennett’s novel “The Reagent” saved their lives. As for the Harris couple, Mr. Harris was a Broadway producer who saw his wife off onto a lifeboat and died with 1,513 others on the ship.

David Blair could thank White Star line corporate red tape for saving his life. He had been appointed as second officer of the Titanic, sailing with her during her sea trials, and making the trip from Belfast to Southampton. But he was not on board when the Titanic set sail for America. It is thought that the White Star line wanted Chief Officer Henry Wilde to have experience aboard a ship (the Titanic) he might someday captain, so Wilde was transferred from the Olympic to the Titanic, and Blair sent over to the Olympic. Good for Blair, not so good for Wilde. This move bumped Chief Officer Murdoch back to First Officer and First Officer Lightoller back to Second Officer. It also caused confusion as the ship was about the depart for America. In his rush to get off the Titanic and onto the Olympic, Blair took with him by accident, the key to the crow’s nest telephone. Most importantly, as it would turn out for the men in the crow’s nest keeping watch for ice that fateful night, Blair also mislaid the crows nest binoculars. Blair had stowed the lookout’s binoculars in his cabin and failed to inform anyone aboard the ship. When lookout Frederick Fleet went for them, they were not there. So Fleet had no binoculars when he was in the crow’s nest, looking for ice.

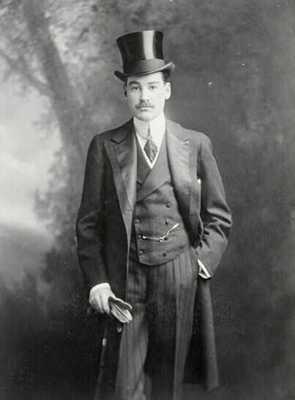

A member of the famous Vanderbilt family, Alfred Vanderbilt was not only extremely wealthy, he was also a dedicated sportsman. He especially loved riding in horse-drawn carriages with friends (something called “coaching”) and fox hunting. In April 1912, he and his wife were in Europe and on April 9, just before Titanic was to leave on its maiden voyage, he changed his mind and decided not to board the Titanic for America. Someone in their family objected to their sailing aboard the new ship, “because so many things can go wrong on a maiden voyage.” However, their servant, Frederick Wheeler did make the voyage on April 10, 1912 along with their luggage. He sailed as a second-class passenger and died when the Titanic went down.

Three years later, his luck would run out. On a business trip to Europe to buy horses and dogs for his favorite hobbies, he was aboard the Lusitania when a German U Boat torpedoed it off the coast of Ireland. Several survivors reported they last saw Vanderbilt offering his life vest to a child and helping the mother tie it onto the child. Vanderbilt did not survive.

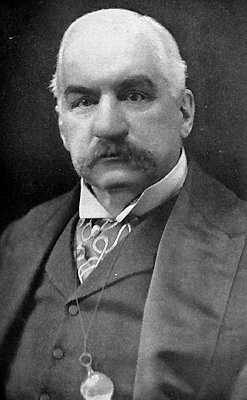

An incredible stroke of bad luck that turned out to be good luck befell three prominent industrial leaders (Henry Clay Frick, JP Morgan, and J. Horace Harding) who were all set to board the Titanic, in April 1912. The three are linked so I listed them as a single entry. Henry Clay Frick, one of the wealthiest Americans of the early 20th Century with vast holding in steel manufacturing, originally booked passage for himself and his wife aboard the Titanic, in February 1912. But while they were in Europe, Mrs. Frick suffered an accident in Madeira and sprained her ankle. Upon arriving in Italy she was admitted to a hospital. This caused a delay in the travel plans for the Frick’s and they were forced to give up their suite aboard the Titanic. Instead, the suite (B-52, 54, and 56) went to JP Morgan. Morgan was, of course, one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the world in 1912, with his vast banking fortune. But Morgan himself was forced to alter his travel plans when he decided to prolong his visit in Europe. The reservations were once more turned over, this time to J. Horace Harding and his wife. Harding was another prominent banker. But the couple was able to get an earlier sailing date aboard Mauretania. The unlucky suite would eventually be taken by White Star Line Chairman J. Bruce Ismay.

The Reverend J. Stuart Holden was the vicar of St. Paul’s Church, London. He had made plans to depart for America aboard Titanic to speak at the Christian Conservation Congress (a six-day convention opening at Carnegie Hall on April 20). However, like Henry Clay Frick, his plans were interrupted by his wife’s sudden illness. On April 9, one day before sailing, the Rev. Holden postponed his trip to stay at his wife’s side.

Holden returned his Titanic ticket, but he held onto the envelope in which it has been delivered. The envelope was subsequently framed and today is on exhibit at Liverpool’s Merseyside Maritime Museum. The yellowed envelope has black-and-red printing that states it contains “First Class Passenger Ticket per Steamship… Titanic” (the word Titanic is written in by hand). Thankful for his salvation, Reverend Holden also wrote on the envelope a passage from Psalm 103, verse 3, “Who Redeemeth Thy Life From Destruction.” This was Holden giving thanks not just for himself, but for all of those who, for what ever reason, did not board the Titanic.

Amazingly, the Reverend Holden was not the only clergyman planning to attend the Christian Congress who did not sail from England aboard Titanic. Two other European speakers who had been invited to speak at the convocation were also forced to cancel their passages aboard Titanic maiden voyage because of circumstances and a change in plans. Archbishop Thomas J. Madden, of Liverpool, and the Rev. J.S. Wardell Stafford, were thus, also not on board when the Titanic sank.

Milton S. Hershey was a businessman known for inventing the Hershey Chocolate Bar and building the Hershey Chocolate Company, as well as his many philanthropic activities. In 1912, Hershey paid a $300 deposit for a first class passage aboard the White Star Line and her newest most extravagant ship, Titanic, for her maiden voyage. However, in spite of the deposit, Hershey never boarded the ship. An employee at his company requested that he return early from a trip in Europe to deal with business. Hershey abandoned his original plans and left Europe three days earlier on The America. The ship made it back to the United States without incident.