Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

10 Advertising Lies We’ve All Been Fed

On an intellectual level, we know that adverts lie to us. No one seriously thinks that wearing Axe will get you laid or that changing toothpaste will make your smile more radiant. Yet there are certain basic assumptions we’ve become so used to making that we take them for granted—allowing canny advertisers to screw us over when we least expect it. I’m talking terrifyingly simple assumptions like:

Long, bitter experience has taught most of us that words like “deluxe” usually mean “anything but.” For example, take the McLean Deluxe, a McDonald’s flop that took “deluxe” to mean “full of water and seaweed”.

But what about words with clear definitions, like “light” or “low fat”? Well, last year a consumer group ran a study that concluded the health difference between “light” and regular options was almost nonexistent. In one example, the study compared “light” with “normal” biscuits and found just eight calories of difference, while another measured the fat in “lighter” cheddar and concluded that it was still dangerously high.

The trouble is that advertisers play on the vast gap between a term’s legal meaning and its regular one. So while “lighter” cheddar may have the required thirty percent less fat, it’s still a guaranteed future coronary. Even worse are ambiguous words, which essentially get a free pass. So we get “premium” vodka that tastes like gasoline, and “improved” flavors that taste like lies.

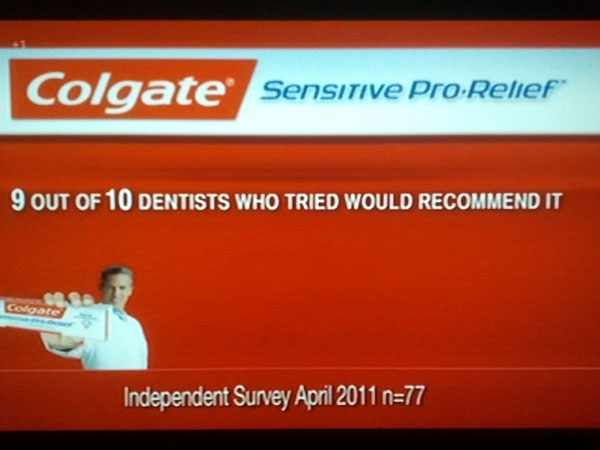

Most of us are familiar with the concept of “cherry picking;” that’s why we automatically tune out wild claims like “97% of women prefer Dove deodorant”. But numerical fudging affects entire industries. Fish oil is a good example: a couple of years ago a slew of companies triumphantly declared that trials had “proven” fish oil helped school children concentrate. They had data, figures, and serious-sounding statistics; they couldn’t be lying.

Except they could and they were. The data came from a laughably small study on Omega-3, not on fish oil. Meanwhile an actual study into fish oil proved that it made no difference whatsoever. Yet fish oil pill sales boomed. Turns out that stuff like this goes on all the time in the health industries.

Most of us are big enough to admit that we don’t know everything. That’s why we look to experts: so that they can bring us up to speed on topics about which our knowledge may be lacking. Which is great and all—except when the “experts” are jerks.

Last year, the drug company Pfizer was forced to shell out $60 million when it turned out that employees were bribing doctors to recommend their products. While this was a massive scandal, similar stuff crops up all the time. Whether it’s doctors rehashing company press-releases, or people making up credentials to sell you useless medicine, “experts” are often no more trustworthy than anyone else on the payroll.

We need to ask ourselves: is it more likely that a group of doctors really came to the conclusion that Walmart lard is good for our cholesterol, or that someone sent them a crate of champagne in exchange for a lazy quote?

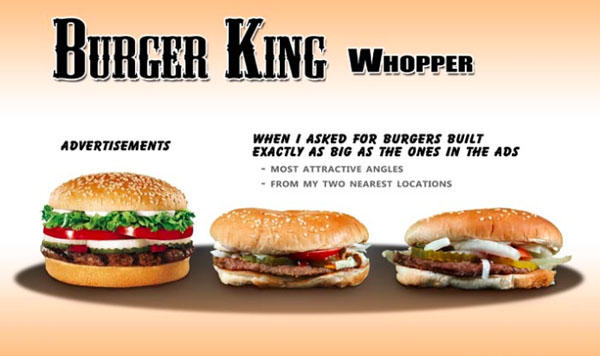

If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably lost count of the number of times you’ve drunkenly staggered into McDonalds, seduced by the warm smell and mouth-watering pictures—only to wind up eating something that looks like it just came unstuck from the bottom of a hobo’s foot. It has become so endemic that one guy even started a photo blog just to compare the adverts with reality—and the results are as depressing as they are expected.

Although companies are legally obliged to use real food in their promotional pictures, there’s no law saying they can’t airbrush it. Pots of glue, motor oil, brown shoe polish; if it can make that crappy burger look appetizing, food photographers will use it. So the moment we enter the store, we’re already suffering from unrealistic expectations.

In the wake of SARS and other scares, the market for hand sanitizer was booming. People evidently thought it helped—but what caused this misconception?

That would be companies like Lysol and Kleenex. Around this time, they went out of their way to insinuate that their products would save us from infection—and many people lapped it up, despite the lack of evidence. You see examples of this all the time; one of them is the entire homeopath industry, which is based on a set of unverified statements. Yet we keep on buying those herbal remedies, even when confronted with empirical proof of their ineffectiveness.

It sounds like a no-brainer: if one product fulfills its function (for example “being tasty” or “smelling good”) better than another, then its quality is better by all standards.

But that’s not exactly true. Our concept of “quality” can be pretty easily manipulated by advertising lies. Take the Italian lager Peroni. In the UK it’s an expensive premium drink; in Italy it’s cheap, bland swill for cheap, bland drunkards.

It turns out that human brains are hardwired to believe in hype. In a widely-reported study, researchers showed that people will believe a wine is of a high quality simply because they’re told it has a $90 price tag. Brands take advantage of this; packaging, pricing, and wording is designed to make you associate their product with quality, even when it’s quite possibly worse than the competition.

Even people who are clued-up enough to understand that price doesn’t mean quality will often still be brand loyal. When a man of moderate means goes to buy coffee, and faces a choice between expensive Starbucks, mid-range Folgers and Maxwell House, and a forlorn-looking bag of Walmart own-brand—the man is most likely to choose anything but Walmart.

But here’s the kicker: in a blind taste test, Walmart coffee scored higher than Folgers and Maxwell House, and equal to Starbucks. This wasn’t a one-off; similar tests have proven that people often can’t differentiate between cheap and expensive products.

This all takes a weird twist when you read about the Pepsi vs. Coke challenge. Blind tasters repeatedly named Pepsi the better drink—until they were told it was Pepsi, whereupon they quickly changed their minds. Intrigued, scientists ran a brain scan and found out that the tasters were telling the truth about their enjoyment levels. Pepsi really did start tasting worse once people knew what it was.

How would Pepsi drinkers feel if they were told that they’re more likely to be uneducated, read terrible tabloids, watch lowbrow TV, never leave the country, and rarely leave the house?

All of those statements come from a heavily biased survey with no scientific merit. Yet some people will have read that and thought, “sounds about right”. That’s our old friend confirmation bias rearing its ugly head. The same brain-fart that can make a hardcore Dem believe George Bush had the IQ of asparagus is exploited by advertisers to make us want to buy their brand.

They call it “identity marketing:” the act of transforming consumer products into lifestyle choices. We don’t merely drink Coke; we are “Coke drinkers,” and our drink choice is an extension of ourselves.

The central tenet of advertising is that choice is a good thing. Not only is it common sense, it’s backed up by several studies. Eliminate choice and you’re left with a bleak world full of desperate people, which is why consumerism is such a godsend.

But it turns out that our consumer paradise isn’t exactly doing us many favors either. Our brains, it seems, are the mental equivalent of the jerk you always get stuck behind at checkouts. Faced with an abundance of options, we stress out about choosing the wrong one, become convinced we’ve made the wrong decision, and spend our time in perpetual anxiety.

One study offering participants a choice of two chocolates from either a box of six or a box of thirty found that people who were faced with the smaller box were generally satisfied, while those picking from the larger box reported more frustration and less satisfaction. Other studies into speed dating and pension plans produced similar results. It seems our brains freak out when given too many options, leaving us dissatisfied and unhappy.

There’s a wealth of evidence to suggest that consumer culture is linked to poor mental health—especially in children. A depressing study by The Children’s Society essentially blamed adverts for kids’ unrealistic expectations and often negative self-image. A separate study for UNICEF pointed to the cycle of consumerism as the cause of British children’s comparative misery.

We adults aren’t exactly immune either; those of us who put emphasis on wealth and material gain are more likely to become anxious and depressed when confronted with our lack of possessions, while this study concluded that simply being in “the consumer mindset” is enough to turn most of us into jerks. Yet marketers keep pushing the myth of the “happy shopper,” because if that were to collapse, consumer culture in its entirety would come crashing down.