Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

15 Ads That Fail On All Counts

Advertising has one job: to knock you down and take all your money. If it doesn’t succeed at that, in the eyes of any Don Draper-esque ad exec, it has failed. Certainly it’s not trying to be creative or artistic for its own sake, although it can manage to be that on occasion (and much more so back in the industry’s oft-romanticized heyday). But sometimes an ad can fail on all fronts, not passing for art or consumer enticement, to where it becomes sort of a vacuum-sealed excrement; then it is only left and subject to mockery by all subsequent generations who discover the novelty in it, more than its original point. There is really no shortage of such ‘no sale’ ads, so here’s 15 (and a bonus), preserved and extracted from history for your amusement (and your amusement alone).

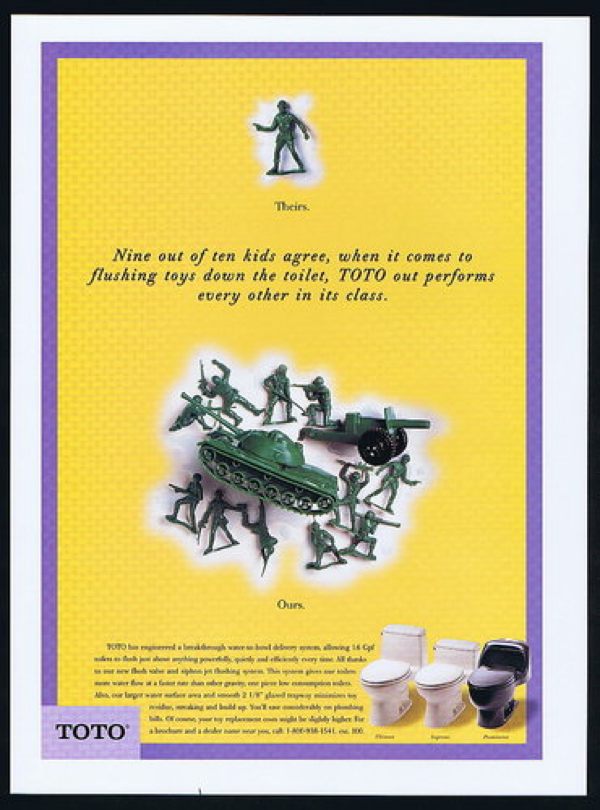

‘Hey mom and dad, guess what?’ this ad implies. ‘Our toilets are great for flushing action figures down.’

‘You’ve sold us already,’ they respond. ‘Because that is exactly what they are meant for.’

Who is this ad aimed at? Clearly it’s aimed at that kid who thinks major plumbing repairs are seminal to his game of army men. But clearly he’s not in charge of purchasing the household toilets. And certainly the parents who are won’t find this ad very cute if they’ve ever had to pay hundreds or thousands for an emergency plumbing job. Obviously the tactic of this ad is humor, but who in the market for a new toilet will find this very laughable (except those those with a delinquent kid for which this is the solution to most of their problems).

Seeing this kind of candor in advertising—or any at all for that matter—is refreshing, even if Buckley’s is anything but. Generally the point of advertising is to attract viewers to your product. The advertising campaign for Buckley’s cough syrup appears bent on the exact opposite. But it is, perhaps, in their defiance of expectations and disingenuous claims that their product stands amongst other, equally terrible-tasting cough syrups that attempt to endlessly convince you that they taste like cherries or bubble gum, and not like laundry detergent. Buckley’s works. Isn’t that all we should care about? Although, you can’t argue that the trash run-off comparisons don’t appeal to the senses.

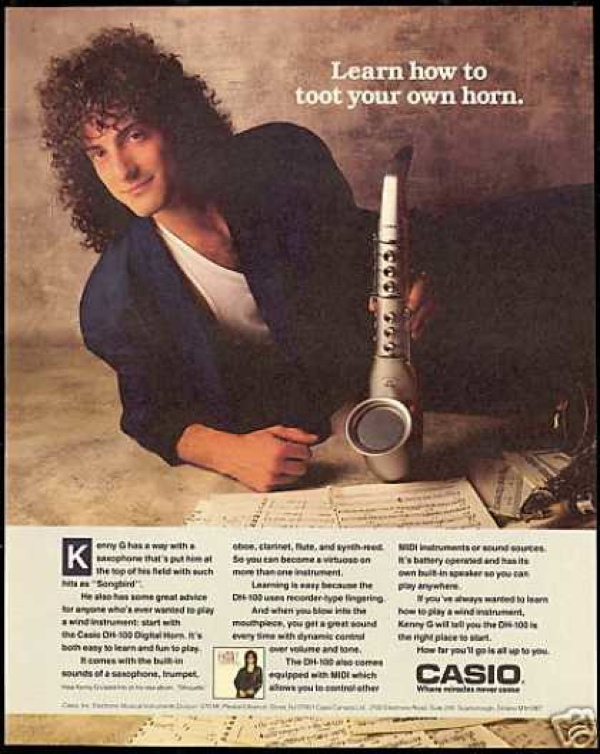

The rule of thumb is: if a popular celebrity endorses something, people will buy it. Therefore it must be true that if Kenny G is endorsing it, nobody’s buying it. Back in the late eighties, early nineties, this guy was a big deal. Much bigger than the laundr-o-mats where his music is most commonly played, here we see him big enough to endorse electronic Casio saxophones, back when saxophones were chic (although they do seem to be making a comeback lately). Today however, Kenny G is just the perpetual butt end of that joke involving loudspeakers and the type of music they play in Hell.

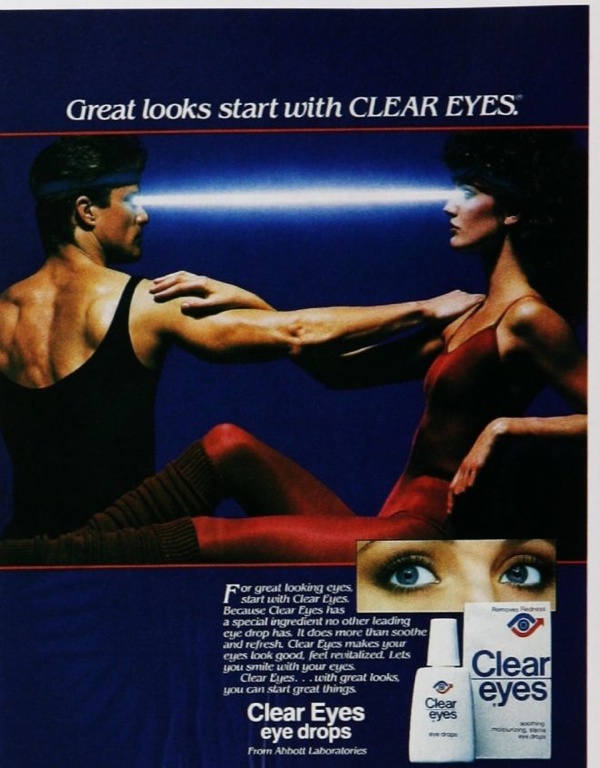

All you can hope from your eyes is clarity of vision and a lack of dryness. Such seems hardly possible when lasers are blasting out of your retinas Cyclops-style as this ad presents. If Clear Eyes does that, perhaps that only time you want to be using them is whilst taking on Magneto and his evil mutant minions. Clearly the two in this ad are dressed for that very task. What the ad fails to communicate is that having clear eyes means powerful eye contact and sexy encounters. Clearly what these two are doing is a bit too intense for any of that. “Great looks start with Clear Eyes.” So do empty sockets where your eyeballs used to be.

There is nothing fancy about this ad, nor does it skirt around the point: hire this man and he will kill your animals. All you must do is provide the life stock, and he’ll handle the rest. Samuel Work, the ad says, “assures all those who may favor him with their killing and dressing that it shall be done with dispatch, and in the very best manner.” Well as long as the killing is done in the very best manner, he’s got our business. Of course ads as such don’t appear these days, for back in those days (1840, apparently), the butcher was basically Applebee’s. And after he’s murdered your cattle, he’ll probably also say, “See you tomorrow.”

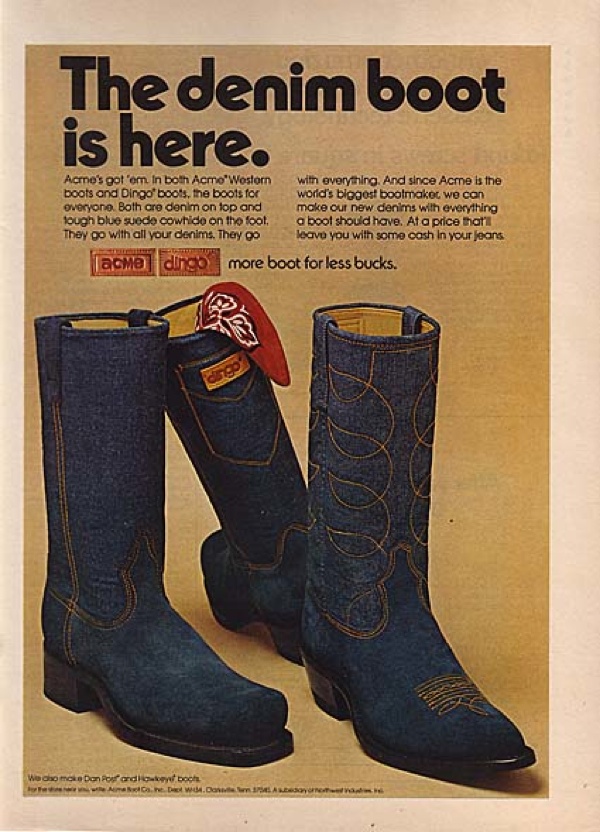

“The denim boot is here,” proclaims 1975, and to a lesser extent this ad. This is the apotheosis of ’70s fashion, in an era dictated by handle bar mustaches, denim jackets, and Eagles (not the band—the animal, be it tattooed or embroidered). It was a time modeled after Easy Rider and where men sought to be rugged and cowboy-like. And what better way to distill each of these sentiments than by a denim cowboy boot. Put them on, the ad seems to say, manhood awaits. If only this ad could see what the ’80s would bring to the concept of masculinity.

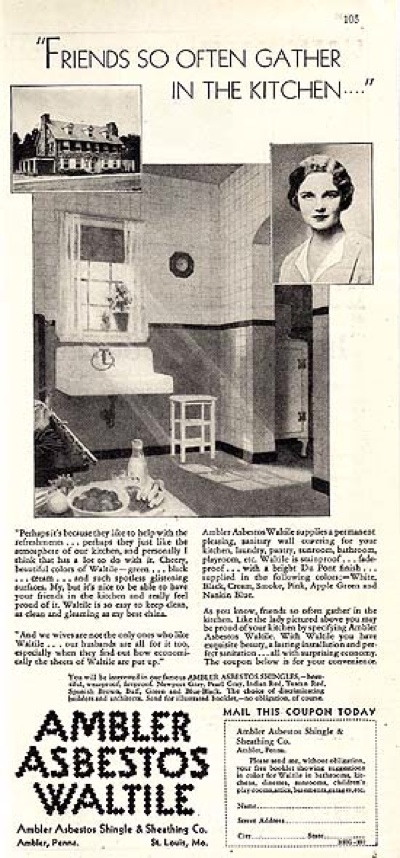

The asbestos industry was almost as stubborn as the cigarette industry. Even as asbestos miners were keeling over and succumbing to health defects in uncoincidental succession, the industrymen behind the material insisted on carrying on business as usual, dismissing health reports. And thusly ads like this were allowed to exist without even a scintilla of morbid humor beneath. This ad for Ambler Asbestos Waltile reads, “Friends so often gather in the kitchen…” And surely they are buried in the basement.

It’s a good thing these donuts are for dogs, because dogs will eat anything, including their own feces. Which is why this brand of ‘Doggie Donuts’ is in luck: they look like dog poop. It seems like a cruel practical joke to make an edible item that resembles fecal waste, and surely PETA would have had a field day with this if they had existed back then. Then again—the other argument goes—they’re dogs, and have no capacity for irony, dramatic or otherwise. And they probably do taste good, in a dog food kind of way. Only in 1967 could that sort of thing go unnoticed; civil rights weren’t even fully-established, let alone doggy-rights. (Note: the ‘Donuts’ from 1973 look far less scatological. Progress?)

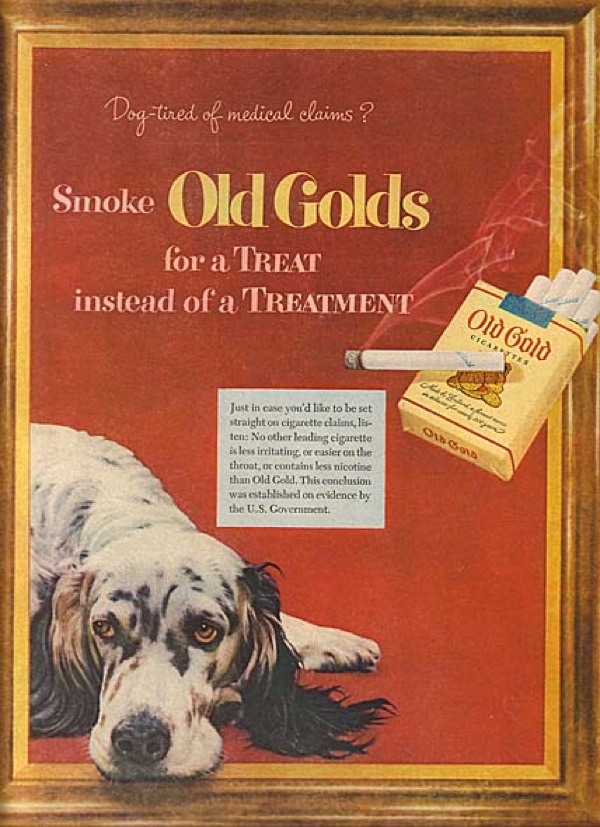

The Archie Bunker-esque message to take away from this ad for Old Gold cigarettes was this: ‘Screw what all them buzzkilling doctors keep yapping about. This stuff makes you feel good. And that’s ALL that matters. Also, here’s a dog. That’s you.’ There was no advertising campaign more belligerent, more fact-resistant, more expensive than that of big tobacco. For a good long while they went unchecked and unquestioned, the dollars flowing in like a nice long drag of tobacco smoke. Then finally when science became a thing and started picking at possible health risks, the industry got defensive and did everything in its power to fight off any potential profit losses. Their money, however, more often than not went into a campaign of deception, rather than refutation. Because there is no refuting conclusive proof, no matter how many ways you try to incorporate words like ‘toasted’ or ‘mild’ or ‘U.S. government.’

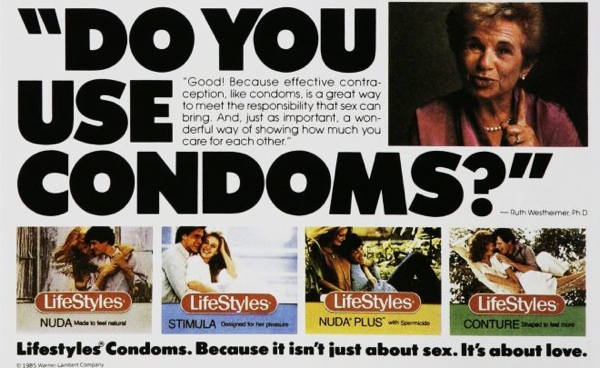

One surefire way to kill the mood: learning foreplay techniques from an randy old German lady. Granted her celebrity status paralleled her identity as a so-called sex doctor, the novelty in the fact does not translate directly to the practice of sex itself. Yet to this brand of condoms, in an era of advertising dominated by celebrity endorsements, her name was gold. In the bedroom, however, her name was a wet towel. Her face betwixt images of young couples getting intimate: mood-death.

Clearly this ad is horrific, with what we know now, and the adverse effects of lead exposure. And, as it turns out, kids are much more susceptible to the dangers of lead poisoning than are adults: they can develop kidney and brain damage, anemia, colic, and ultimately die from it. Yet here we are in 1926, and this boy is swinging from a giant beam with the word ‘LEAD’ stamped on it. Sadly Dutch Boy would likely not grow up to be Dutch Man, thank to this wild dose of negligence (not to mention the rampant lead exposure).

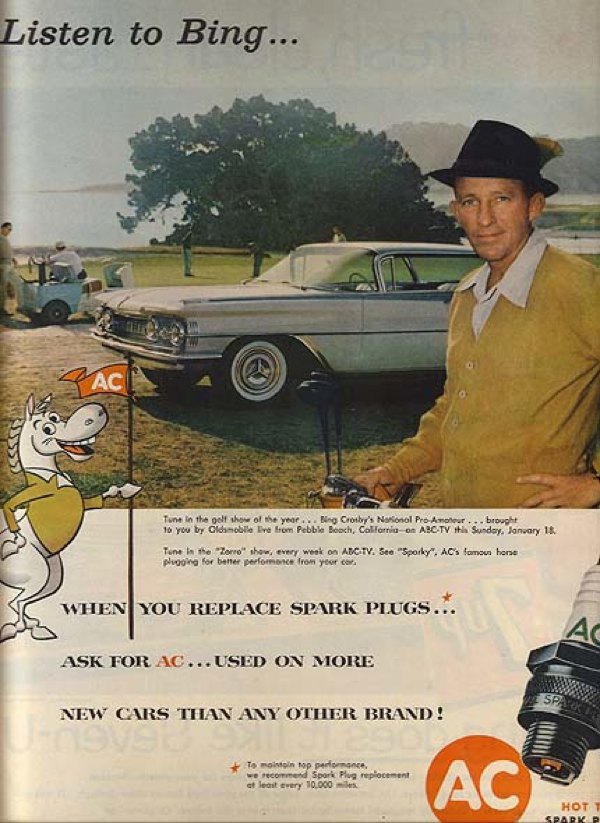

Nothing about this ad seems to make any sense. First off, we have Bing Crosby, best known for…golf? (Actually yes, sort of: he founded the National Pro-Am tournament, and shilled out the $500 purse to the winner from his own pocket). Secondly, what does golf or Bing Crosby have to do with spark plugs? Okay, so the ad says the Pro-Am tournament is sponsored by Oldsmobile, which certainly has something to do with spark plugs. The problem is, the typical consumer and casual golf enthusiast—unless this ad happens to appear in a golfing/automotive magazine—is likely to associate Crosby with “sleigh bells in the snow,” rather than “spark plugs in the car” or “chipping wedge in the bag.” While shameless celebrity-endorsement is a time-honored tradition in the advertising world, the product usually in someway connects to the celebrity at hand (e.g. Michael Phelps and Wheaties, Britney Spears and perfume, Jimmy Johnson and those penis pills, etc.). Here, we rely on too many degrees of separation to make the instant connection. Also, note the subtleties of the ad (which are in no way forced): the car driven up onto the golf course, which no one seems to notice or be bothered by; the animated horse wearing the same green button-up as Crosby, and no pants; the implication that Crosby somehow needs you to know about this brand of spark plugs, as the above caption reads, “Listen to Bing…” Sure, we’ll listen to Bing, especially right around the 25th of December, but if our cars need new spark plugs, chances are we’ll listen to what the family mechanic has to say first (even if he can’t croon in a silky baritone).

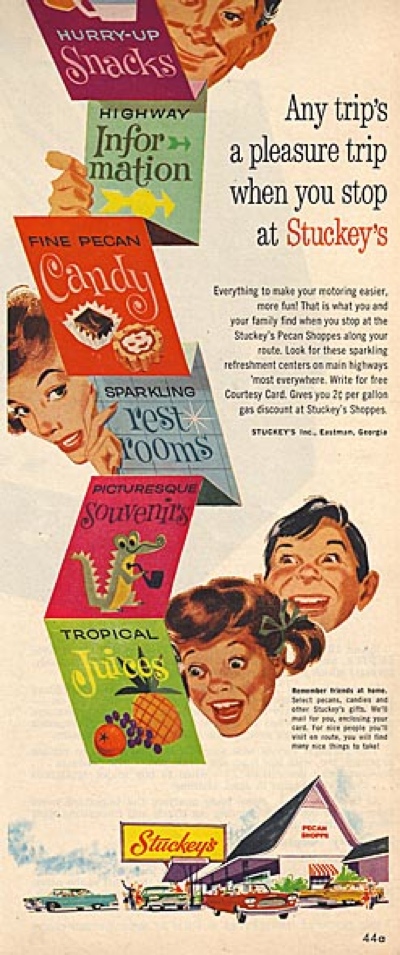

Come to Stuckey’s, we’ve got sparking restrooms. And if that’s not enticing enough, we’ve also got highway information. Stuckey’s ‘Pecan Shoppes’ sell themselves as essentially a glorified rest stop. Where it falls short is in how it does the ‘glorifying.’ For a store specializing in ‘fine pecan candy,‘ a little too much emphasis, and a few too many unironic adjective choices, are placed on the less-than-novel aspects of the novelty store. It is clear who the target audience is—your average American family— but the way that boy is looking at those ‘picturesque’ souvenirs suggests that this is not an average family. One thing remains true: rest stop toilets have never looked more appealing (NEVER).

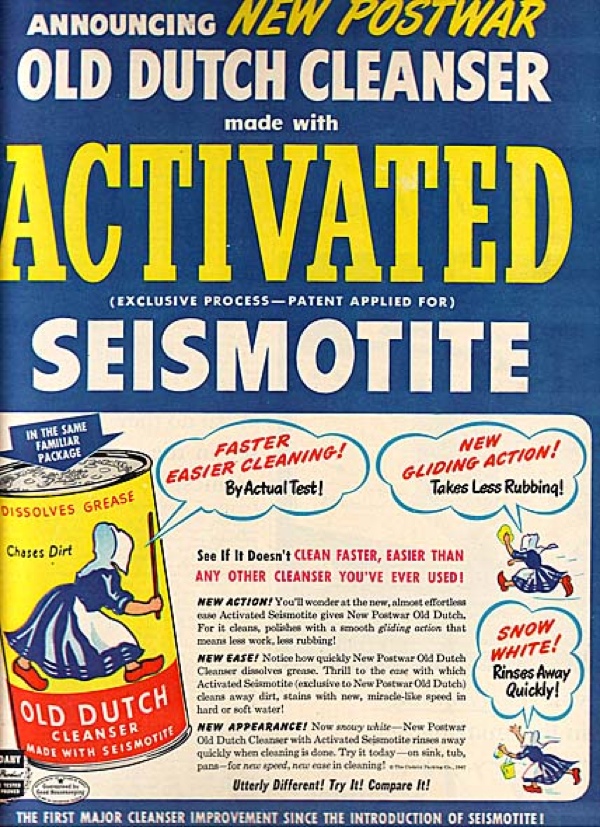

Your average consumer, nor housecleaner for that matter, is no geologist, let alone knows what seismotite is. And to make this ingredient the selling point of your cleaning product is to ask for a lot of silent returns. Seismotite, as it turns out, is another word for pumice, which is a type of vulcan rock used as a scrubbing agent in cleaning products. And now we know. Yet back in the 1948, when this ad displayed the name of this substance as the second largest word in the ad (after ‘ACTIVATED’), how many consumers had the sudden urge to run out and buy some Old Dutch? And then there’s the mascot: a frantic, cloaked old Dutch woman wielding a stick, who makes household chores look like s&m. At least Mr. Clean always looked happy doing his job. Maybe it’s because he was never expected to crack open a geology textbook every time he wanted to give the kitchen a once-over with a mop.

Meat isn’t meant to be shaped like that. Nor should it share the skin pigmentation of the Social Security-recipients who buy it most. Nor, also, should it contain enough inorganic ingredients to render it more of a polymer than a meat product. Truly this stuff is imported straight from the Island of Dr. Moreau, and with its unnatural shelf life, Spam is probably still drawing from the first batch of pig sludge that was originally whipped up back in 1937. These days Spam has come to be synonymous with everything undesirable in this world (e.g. ‘canned-ham’ in sitcoms, spam email, etc.)—which is not to mention the risk of cancer attributed to regular processed meat consumption. When your meat becomes a punchline, it can no longer be treated as a serious food.

This ad is 76 seconds long; the legal disclaimer lasts for 40. During those 40 excruciating seconds of horrible side-effects—most of which (i.e. death) are far worse than the original diagnosis—we see visuals of smiling families doing happy things, like watching sunsets on marinas and hugging fathers. The impression conveyed is a twisted, disjointed one, like a scene out of a David Lynch movie. But as far a the tone of the commercial goes, it’s all completely matter-of-fact, as if that middle 40 seconds of the ad spent scaring us to death is going to induce us to ‘ask our doctor’ about this product. (Then there’s the fact that one of the side effects for this anti-depressant is ‘thoughts of suicide.’ …Huh?) The only question we could possibly ask is: how are these murder-pills legal (let alone FDA approved)?