Pop Culture

Pop Culture  Pop Culture

Pop Culture  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Activities That Were Once Considered Illegal

History

History Ten of History’s Hidden Secrets: Stories 99% Don’t Know About

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Who Infamously Stormed Off Set While Filming

Food

Food 10 Foods That Have Alleged Occult Powers

Sport

Sport 10 Lesser-Known Multi-Sport Alternatives to the Olympics

Humans

Humans 10 Real Life Versions of Famous Superheroes

Gaming

Gaming 10 Overused Game Villains

Mysteries

Mysteries Ten Mysterious “Ghost Ship” Stories That Still Keep Us Wondering

Technology

Technology 10 Times AI Replaced Humans (and No One Noticed)

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Things You Might Not Know about Dracula

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Activities That Were Once Considered Illegal

History

History Ten of History’s Hidden Secrets: Stories 99% Don’t Know About

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Who Infamously Stormed Off Set While Filming

Food

Food 10 Foods That Have Alleged Occult Powers

Sport

Sport 10 Lesser-Known Multi-Sport Alternatives to the Olympics

Humans

Humans 10 Real Life Versions of Famous Superheroes

Gaming

Gaming 10 Overused Game Villains

Mysteries

Mysteries Ten Mysterious “Ghost Ship” Stories That Still Keep Us Wondering

Technology

Technology 10 Times AI Replaced Humans (and No One Noticed)

10 Forgotten And Unrecognized Inventors

Spend some time researching the history of technology and it soon becomes clear why scholars don’t like the term “inventor.” For everyone credited with inventing something, you’ll always find someone else who beat them to it.

Sometimes it has simply been a matter of publicity. Thomas Edison claimed he was the inventor of several items—the motion picture, the incandescent light bulb—all the while knowing that others got there first. The Wright brothers probably weren’t the first to fly a powered air machine—but at least they had the photos to prove they got airborne.

The people in this list deserve credit for their inventions—but maybe it would be better if we just dropped the idea of the “lone genius” altogether, and learned to spread the credit around.

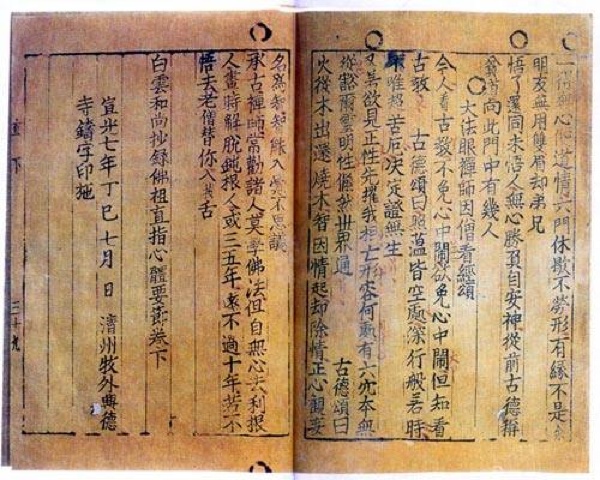

Almost exactly two hundred years before Johannes Gutenberg invented his printing press, Koreans started producing books using moveable metal type. Credit for this is generally given to Choe Yun-ui, a civil servant with the responsibility for printing the Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun, a massive collection of historical documents and legal codes.

So why did Gutenberg get the recognition, and not Choe or his team?

One problem was that the type being used was Chinese script and amounted to thousands of characters. Although moveable type cut down on the work the process was still arduous. It wasn’t until the 1440s and the introduction of the Hangul alphabet that the country had a writing system that would work efficiently with the printing press. But more than that: hemmed in by China on one side and Japan on the other, Korea was isolated from the West. The first Westerners to stay in the country and report on it were Portuguese missionaries at the end of the sixteenth century—but it wasn’t until the nineteenth that there was anything like regular contact. By then Europeans took it for granted that they ruled the planet, and weren’t too impressed by what an Oriental country had invented six hundred years ago.

Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi probably flew from Europe to Asia in 1630. In Istanbul, the width of the Bosphorus Strait that separates the Asian from the European side is less than a mile in parts—so no, we are not talking about a flight from Paris to Beijing. Still, this was 1630 and in Western Europe the science of aeronautics, such as it was, had basically started and finished with Leonardo da Vinci a century earlier.

Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi probably flew from Europe to Asia in 1630. In Istanbul, the width of the Bosphorus Strait that separates the Asian from the European side is less than a mile in parts—so no, we are not talking about a flight from Paris to Beijing. Still, this was 1630 and in Western Europe the science of aeronautics, such as it was, had basically started and finished with Leonardo da Vinci a century earlier.

Unfortunately, the flight doesn’t get a very detailed description in the Ottoman records and we can only guess what the glider looked like, but if Çelebi had knowledge of some basic principles, aeronautic engineers see no reason why he couldn’t have done it.

What happened to Çelebi after his flight is a bit of mystery—but from what we do know, it doesn’t sound good. He was apparently a respected mathematician and scientist in Ottoman Constantinople—but whether because of the flight or some other matter, he was banished shortly afterwards to Algeria, which in terms of the Ottoman Empire was as far away as possible.

But wait, there’s more:

Yes, Ahmed had a brother, Hasan, and if there is any substance to the story of what he achieved then Ahmed’s story is actually a bit of a squib. A year or two after Ahmed made his flight, Hasan took off for the heavens in a rocket.

As part of the celebrations for the birth of the Sultan’s daughter, Hasan built a rocket and took off from the shore below the Topkapi Palace. Before we dismiss this as fanciful, there are a couple of points to consider. Firstly, gunpowder, which was apparently used to launch the rocket, was available and had been used by the Chinese in rocket fireworks for several centuries. While it might have provided enough charge to get the craft skywards, something else would have to kick in to keep it up there.

The other issue is how he got down. Given that both brothers were scientists working from a library of Islamic science, he could have easily figured out that some form of parachute was necessary. Alternatively, the rocket was described as having seven wings, so it is conceivable that he was able to guide the craft down. In other words, the point might not have been to reach the stratosphere and beyond, but show off some development in rocketry.

Like his brother, Hasan fell foul of the Sultan—but he was merely exiled to the Ukrainian coast, where he may have continued his research into rocket power.

You’d think, wouldn’t you, that these days students would have some idea about the history of computers—but it’s surprising how many assume everything started with Bill Gates. Watch their expressions of disbelief when you tell them the person who wrote the first computer program was a woman—and that she wrote it in 1843. And by the way, she was Lord Byron’s daughter.

The year before, Ada Lovelace’s friend Charles Babbage had given a lecture on his “analytical engine,” a machine intended to calculate logarithms and trigonometric equations. An Italian engineer, Luigi Menabrea, took notes in French and later published an article. Babbage asked Lovelace to translate that into French. During the process, she wrote up a series of algorithms of her own, including one that calculated Bernoulli numbers, which she realized would give the engine functionality. It was the algorithm using the Bernoulli numbers in particular that would be considered the first computer program.

Here the story becomes tragic. Babbage was a notorious misanthrope who refused to get along with just about everyone else. As the result of an argument with his engineer and the denial by several organizations of necessary funding, the Analytical Engine was never completed. Lovelace meanwhile contracted cancer and died in 1852, aged just 36. It wasn’t until the 1950s that her writings were republished, and many scientists became aware of just how astonishingly advanced her thinking on computers was.

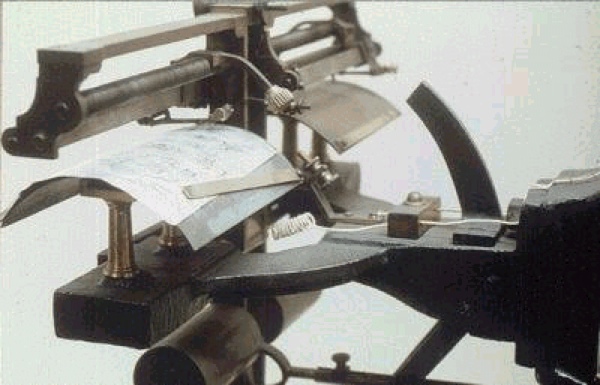

What happened on a Lyons railway platform during the week before Christmas 1874 would have made a steampunk novelist proud of himself. An unnamed clerk had run away from a Paris business with a wad of cash. No doubt thinking he had time on his hands, he disembarked at Lyon and was promptly surrounded by detectives. One of them waved a portrait of him they’d received from Paris, transmitted by telegraph probably while the train was still on the outskirts of the capital.

Giovanni Caselli’s pantelegraph worked like this: Two styli, the sender and the receiver, were regulated by electric clockwork so that when the sender inscribed part of the image the receiver—potentially located in a different city—was able to simultaneously trace it on a disc. The pantelegraph was in operation in France until 1870. Why it fell from use might have had something to do with the invasion by Prussia that year and the subsequent siege of Paris. Still, that was sorted within a year and why it was never revived is perhaps the strangest element of the whole story. When you think of all the other technologies that emerged at that time and where they were taken, the fact that nobody saw the real potential of being able to transmit facsimiles electronically is utterly mysterious.

Thirteen years before Orville took off in the Wright Flyer I, Clément Ader pulled off the same feat—a successful flight in a manned, heavier-than-air, powered aircraft—in the Éole.

There were hundreds of inventors working on aircraft at the time, but Ader was one of a handful who were taken seriously. He had already designed and patented devices useful in acoustics and electronics, and in the spirit of the age branching out into aeronautics was logical. On October 9, 1890, he took off in a field and flew approximately 165 feet (50m).

But there were problems: Firstly, it appears there was only one witness. Secondly, the plane reached an altitude of a mere eight inches (20cm); and thirdly, during another attempt a few years later in front of representatives from the Ministry of Defence, Ader’s plane hit a wind gust, reportedly flew about 1000 feet but crashed and the various representatives grumbled and walked away.

Had a photographer been present on that first attempt, history might have been written differently. As for the altitude? Well, eight inches is still technically airborne. It is generally accepted among historians of flight that Ader did fly that day in 1890. He appears to have lost interest in designing his own plane after the debacle with the bureaucrats, but carried on championing the cause. In 1910 he published a book, L’Aviation Militaire, wherein among other things he foresaw a time when aircraft would be housed on ships from which they’d take off on short-range raids.

Regardless of what Thomas Edison claimed, no one invented the cinema. A sequence of innovations introduced around the world paved the way for the final outcome. If one of the many inventors who had a part in the creation of cinema deserves an accolade, it’s Henry Heyl.

The story usually goes something like this: In 1873, Muybridge photographed the racehorse Occident in a sequence of photographs. By 1879 he was exhibiting his sequences of animals in motion through a device he called the zoopraxiscope. The problem was that because the zoopraxiscope projected images from a rotating disc, Muybridge had to distort the images so they’d appear on the screen naturally. For that reason he couldn’t project photographs—and this was the problem others tried to overcome during the next ten years.

Go back three years before Muybridge photographs Occident, and on the night of February 5, 1870, Henry Heyl puts on an exhibition for an estimated 1600 people at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. The show is brief—a sequence of photographs of a couple dancing for just a few seconds is projected repeatedly on a screen—but it is enough to enthrall journalists throughout the US, and is reported in several newspapers. Heyl called his device the Phasmatrope. It appears that he only exhibited it once, and then disappeared.

Well, not entirely. A few years later he came up with another invention—the stapler.

Nathan Stubblefield might just be the best known inventor on this list. Historians of radio and communication will admit the farmer from Kentucky did invent a form of radio a few years before Marconi and Tesla laid claim to it. Their uncertainty has to do with his process, which relied on induction rather than wireless transmission. Induction transmission worked by sending radio signals between metal rods. It worked—but only over short distances. What we know as wireless transmission, which was already close to being realized at the time, could send a signal over hundreds of miles.

Nathan Stubblefield might just be the best known inventor on this list. Historians of radio and communication will admit the farmer from Kentucky did invent a form of radio a few years before Marconi and Tesla laid claim to it. Their uncertainty has to do with his process, which relied on induction rather than wireless transmission. Induction transmission worked by sending radio signals between metal rods. It worked—but only over short distances. What we know as wireless transmission, which was already close to being realized at the time, could send a signal over hundreds of miles.

But so what if it wasn’t the breakthrough everyone wanted? The remarkable thing about Stubblefield is that it appears he had no formal background in electronics or physics. He did possess a remarkable ability to think through abstract problems and work out a process.

To Stubblefield belonged the saddest end of anyone on this list. He went into partnership with a group of businessmen who were more interested in publicizing themselves than Stubblefield or his invention—and within a few years, he realized that he was being ripped off from all directions. Bitterly disappointed, he retired to a mountain shack where he lived in isolation. There he starved to death in 1928—the same year NBC went coast to coast.

The story goes that on the night of Christmas Eve, 1883, German physics student Paul Nipkow was alone at home and began thinking through a problem. How could he improve on the electronic transmission of images? In his mind’s eye he saw something we could think of as a cross between Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope and a vinyl LP; a single groove on the disc punctuated by a regular sequence of square holes could capture a whole image as a series of fragments.

If that sounds like pixels, it isn’t far off. It made possible the sending of images from a transmitter with a Nipkow disc to a receiver containing one, a key element being selenium cells that could convert light into electric pulses. Unfortunately the images were small and poorly focused—but without the Nipkow disc, TV wouldn’t have been possible.

By the 1890s Nipkow was working full-time designing electrical components and no longer interested in the potential of his invention, but he was invited to the first public exhibition of television in Berlin in 1928 and studied the weak images, aware of the role he’d played forty years earlier in getting them there.

You might already know the official history of the invention of photography: In the 1820s, Frenchman Nicéphore Niépce created what is considered the world’s first photograph. The exposure time was ridiculously slow, at more than eight hours, and Niépce handed over his research to his friend Louis Daguerre, who claimed invention of the Daguerreotype in 1839. Meanwhile, across the English Channel, British scientists William Fox Talbot and John Herschel had been working on their own process involving paper negatives that could be reproduced as positive prints.

Unofficially there were several others at the same time that claimed to have invented the medium—and most have some justification. By the late 1830s, all the information needed to create photographs was available. It was a matter of putting it in the right order.

News travelled slowly in the 1830s, particularly if you lived in the small river port of São Carlos in the Brazilian jungle—so it was a while before French expatriate Hercules Florence heard what Daguerre and Fox Talbot had been up to. In 1832 he had begun working on a process to print photographic images using silver-nitrate, and to fix them with urine. The process was reportedly working by 1834 and that year he hit upon a name for his invention; photographie. He beat Herschel to that by a few years. Although he published some of his results in a local newspaper in 1839, he was more or less forgotten until the 1970s, one hundred years after his death in 1879.

Only two of Florence’s photographs are known to exist, one of a certificate and the other a self-portrait.

John Toohey is an author, photohistorian and the blogger behind One Man’s Treasure.