Animals

Animals  Animals

Animals  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things People Used to Do at New Year’s

Our World

Our World 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2025 That Refined History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know About Snow

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Top 10 Things Crypto Was Supposed to Change & What Actually Did

History

History 10 Huge Historical Events That Happened on Christmas Eve

Music

Music 10 Surprising Origin Stories of Your Favorite Holiday Songs

History

History 10 Less Than Jolly Events That Occurred on December 25

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Funny Ways That Researchers Overthink Christmas

Politics

Politics 10 Political Scandals That Sent Crowds Into the Streets

Animals

Animals 10 Species That Refused to Go Extinct

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things People Used to Do at New Year’s

Our World

Our World 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2025 That Refined History

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know About Snow

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Top 10 Things Crypto Was Supposed to Change & What Actually Did

History

History 10 Huge Historical Events That Happened on Christmas Eve

Music

Music 10 Surprising Origin Stories of Your Favorite Holiday Songs

History

History 10 Less Than Jolly Events That Occurred on December 25

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Funny Ways That Researchers Overthink Christmas

Politics

Politics 10 Political Scandals That Sent Crowds Into the Streets

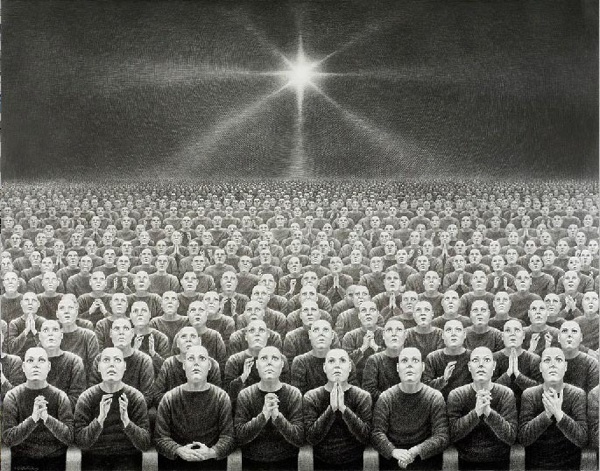

10 Mind-Bending Implications of the Many Worlds Theory

In quantum physics—the scientific study of the nature of physical reality—there is plenty of room for interpretation within the realm of what is known. The most popular mainstream interpretation, the Copenhagen interpretation, has as one of its central tenets the concept of wave function collapse. That is to say, every event exists as a “wave function” which contains every possible outcome of that event, which “collapses”—distilling into the actual outcome, once it is observed. For example, if a room is unobserved, anything and everything that could possibly be in that room exists in “quantum superposition”—an indeterminate state, full of every possibility, at least until someone enters the room and observes it, thereby collapsing the wave function and solidifying the reality.

The role of the observer has long been a source of contention for those who disagree with the theory. The strongest competition to this interpretation, and probably the second most popular mainstream interpretation (meaning, a lot of incredibly smart people think it’s a sound theory) is called the Everett interpretation after Hugh Everett, who first proposed it in 1957. It’s known colloquially as the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI), because it postulates simply that the wave function never collapses; it simply branches into its own unique world-line, resulting in every possible outcome of every situation existing in physical reality. If you’re having a hard time getting your head around that statement (and the fact that it’s held to be correct by the likes of Stephen Hawking), allow us to spell out some of the implications for you—but first, you may want to plug your ears to hold your brains in.

You’re probably familiar with the concept of “alternate universes,” and if so, probably because you’ve seen it in fiction. After all, one of the very first instances of the concept appeared in DC comics, first touched upon in a couple of issues of Wonder Woman, but firmly established in a 1961 issue of The Flash. The fictional “Multiverse” concept established by DC, and taken further by Marvel, is simply the concept that there exists infinite alternate realities, each containing separate and unique versions of their characters, which exist outside one another and often cross over.

This is the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics in a nutshell (without the crossing over, so far as we know). It states that since the wave function never collapses, every possible outcome of any event is realized in a separate and non-communicating physical reality, which actually exists alongside our own. It is interesting to note that this seemingly coincidental use of alternate realities, perfectly describing MWI, was put forth in a fictional medium just four years after Everett’s initial proposal of the interpretation. If MWI is correct, it is certainly not a coincidence—for fiction may be more than just made-up stories, as we’ll see later.

At any rate, this means that there is a version of you whose car broke down this morning, forcing you to take the bus (or, if that happened this morning, then vice versa). There’s also a version of you who was attacked by a dive-bombing kamikaze bald eagle, for this doesn’t just apply to mundane stuff; as a necessary consequence of Many Worlds, it must hold that…

Let’s consider an NFL football game being played. Assume that every time the quarterback throws the ball, there is a gigantic invisible die being rolled, a die which contains an infinite amount of values. The most common, likely outcomes—receiver catches the ball and scores, catches the ball but gets tackled, ball is intercepted, and so on—are assigned to a very high number, perhaps billions, of values. Very unlikely outcomes—say, the ball bounces off of the sole of the sprinting receiver’s shoe as he is hit by a linebacker, is barely scooped up off the turf by a running back, who somehow eludes all the tacklers and scores—are assigned to a low number of values. But crucially, they are still assigned.

MWI concludes that all values are rolled in some timeline somewhere, even the most unlikely ones—and inevitably, the timeline where the low-probability value gets rolled will be ours. As evidenced by the play described above, which totally happened and decided the outcome of a divisional playoff game.

And there is no ceiling of improbability, other than physics—whatever could possibly occur.

We have no way of knowing whether or not even those physical laws remain consistent across all possible world-lines, because we unfortunately can’t communicate with or visit them to ask. So even when confronted with circumstances that appear to be impossible, like a glowing ball of light that shoots fireballs at a police helicopter, or a missing woman unknowingly standing in the background of a photo being taken of her family for a newspaper story about her disappearance, it helps to remember that nothing is impossible on a large enough scale—indeed, given an infinite number of chances, literally anything you can imagine is not only possible, but inevitable. And just as inevitably, the impossible or unimaginable—given billions upon billions of chances—will happen here in our world-line. Which leads to a couple of interesting observations about human nature…

If you find it impossible to imagine a man inexplicably killing a bunch of people for no reason, or someone surviving injuries that would destroy a normal person five times over, or a pilot managing to land an airplane with all controls restricted or disabled without incurring any major injuries, you may be finding it a little less impossible now—considering what we know about how probability works in a Multiverse. But as soon as we begin to apply this to ourselves personally, the implications threaten to become overwhelming; for there are billions of versions of you—all of which are undeniably you—but many of which are very, very different from the “you” of this world-line.

The differences between those versions are as staggering and vast as your imagination, and the reality of their existence forces us to examine human nature a bit differently. Of course, you would never kill anybody (we hope), but have you ever thought about it? There is a world-line where you did. In fact, there’s a world-line where you’re the worst mass murderer ever. Conversely, there’s another where your tireless efforts and dedication to the cause brought about world peace. Did you have a band in high school? That band is the dominant musical force on the planet, somewhere. Have you always kind of wondered what would have happened had you mustered the guts to ask out that one girl or guy that one time? Well, you get the idea.

This could actually explain a lot: strong feelings of deja vu, feelings of a close connection with someone you’ve never met, morbid fascinations with things that should repulse us, or even instances of people acting strongly “out of character” in our own worldline. For as we will see, some may have a degree of “resonance” with other world-lines or versions of themselves, which can bring about the knowledge that:

Hinduism, along with some other schools of religious and philosophical thought, teaches the concept of reincarnation—that we as human beings manifest physically on Earth multiple times, that we can learn from our past and future “lives,” and that such learning is in fact the purpose of our existence. This belief system can be seen as an intuitive understanding of the Multiverse; and given our previous assertion about you being a mass murderer, it can be comforting to know that the experience of all facets of human nature is an explicit part of our growth.

Of course, this is not to say that anyone should kill people or engage in any other immoral behavior—after all, the purpose of this continued cycle of learning (according to Hindu belief) is to eventually learn all that there is to learn, and transcend our physical existence. Ideally, we learned many lifetimes (world-lines) ago all there was to learn from indulging the dark side of our nature.

But the kicker here is that our experience is our experience (an idea we’ll get to in a little more detail shortly)—and that all of human experience must be realized by every one of us before we can move on to wherever it is we’re moving on to.

While some believe that our destination is a type of eventual godhood, wherein we all get to preside over a universe of our own creation, others believe that the cycle simply repeats—that once everything runs down and heat death results in the destruction of all realities, our accumulated knowledge will be used to restart the cycle and create the next Multiverse. Which, of course, means that…

If reality is a continuous cycle—along the lines of “Big Bang, expansion, contraction, collapse, Big Bang again”—then, given what we believe about the Multiverse and its infinite world-lines, you have existed before. In fact, all the infinite versions of you have existed before, and will exist again—and the same goes for all of us, along with every possible idea, creation and situation throughout all of our past and future, across all realities.

In one fell swoop, this concept explains instances of both deja vu and strong feelings of predestination. Even if deja vu seems meaningless and random, and the premonition turns out to be incorrect, these things are only true of our particular world-line—and it appears that some people (or all people, just to varying degrees) are able to achieve some degree of “resonance” with alternate world-lines—another concept that first appeared in comic books.

Indeed, one of the more common forms of deja vu involves experiencing an event which we recognize from having previously dreamed it. While seen by some as precognition, this really suggests resonance with alternate (or identical but previous) world-lines—especially when you consider that the “dream world” may be seen as an alternate world-line itself, and one just as real as the waking world.

Of course, if everything that exists or will exist has already existed, this leads to the conclusion that…

Many writers of stories, songs and other artistic types describe a feeling of the pieces that they craft already existing, fully formed, waiting for the artist to come along and excavate them like fossils. In an infinite Multiverse, this makes perfect sense, for this is exactly what the pieces are.

Art is a uniquely human endeavor, and one that strives to communicate aspects of the human experience that may be difficult or impossible to communicate by other means. While it is not possible to accurately describe in any language what love “feels like,” there are plenty of ways to communicate this in art—indeed, it is through artistic expressions that resonate with us (that word again) that many of us develop our first notions of the nature of love—and that’s only one example. How should it be possible for an artist to communicate effectively, through a story, song or painting, an emotion that the reader, listener or observer has never felt before?

In our Multiverse, this is explained by the fact that these expressions of human emotion, thought, and perspective have essentially always existed, for as long as the impulses that spawned them have existed. This very piece of writing, which has been written before in order to guide another version of you to knowledge that you already have, can stand as a perfect example.

For that matter, consider the possibility that stories aren’t just stories. The Marvel Comics Multiverse acknowledges the existence of our world-line, one where superheroes don’t exist but are merely stories in books and movies. It could very well be that—since physical laws may be very different in other world-lines—these are not stories at all, but actual people and events transcribed from other realities. This goes for anything ever “imagined” or “created”—there exist world-lines where Hogwarts School and Harry Potter, Camp Crystal Lake and Jason Voorhees, Gotham City and Batman, all exist in physical reality.

And if you’re thinking that this line of reasoning—everything exists, nothing is ever created—implies that nothing is ever destroyed, well:

That is exactly what it implies. The fact of our immortality in a Multiverse can be illustrated in various ways. For one thing, the First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy (such as the electrical charges generated by your brain, or the heat your body produces) cannot be created or destroyed, but simply changes form—implying that the energy that powers your body must go somewhere when it leaves, and that consciousness cannot be destroyed, but is infinite. For another, consider the thought experiment known as Quantum Immortality.

In this experiment (preceded by “thought” for a reason; for crying out loud, don’t try this), an experimenter sits in front of a device which is programmed, with 50/50 probability, to either discharge a device which kills the experimenter, or produce a click (in which case, of course, the experimenter survives). In the second case, the experimenter and all observers experience the same outcome- a click, and nothing else. But in the first—since (assuming MWI is correct) it is not possible for the experimenter to experience termination of consciousness (because consciousness is infinite)—while any observers will see the experimenter killed, the experimenter himself will experience the first outcome, the harmless click, on another world-line. Said experimenter can never experience a different outcome, and thus—no matter how unlikely it becomes after repeated attempts—will always survive the experiment, from his point of view.

This means that while we will all experience dying, we will never experience death—the termination of our consciousness. How can this be? It calls into question the very nature of consciousness, which leads us to the very real possibility that…

In the late 1970s, physicist David Bohm formulated a theory describing what he called the Implicate and Explicate orders of existence. This theory, which is consistent with MWI, states that there is an enfolded or “Implicate” order of existence which encapsulates all of consciousness, and that there is a corresponding “Explicate” order of existence which comprises all that we physically see and experience, and is the projection of the enfolded “Implicate” order.

Bohm arrived at the controversial conclusion (along with physicist Karl Pribram, who arrived at the same conclusion independently) that the entirety of observable existence is basically the mother of all holograms. Just as a laser filtered through an encoded film produces a hologram, our collective energy of the implicate order (the laser) filtered through our human consciousness (the film) produces the explicate, physical reality (hologram).

Michael Talbot’s excellent book The Holographic Universe examines this and many other aspects of Bohm and Pribram’s theories in detail, but the overarching and inescapable conclusion—which you have likely already drawn yourself—is that:

If the Explicate is but a “projection” of the Implicate, then we—our physical selves, and indeed all of physical reality—are a “projection” of our true, unfiltered consciousness. One that we all play a hand in creating, whether we know it or not, all the time.

This one notion explains practically everything that “can’t be explained” about the world we see. Supernatural phenomena, meaningful coincidences, psychic activity—literally anything and everything makes sense when one realizes that this reality is essentially a dream, dreamed by the most powerful consciousness imaginable.

If this is the true nature of physical reality—as suggested for centuries by Hindu scholars, intuited by generations of artists and philosophers, and articulated as well as possible by our most brilliant scientific minds—then there is only one statement left to be made. Probably not coincidentally, one that was made previously as a seemingly throwaway lyric in a 1967 song, by one of our greatest artists…

Throughout the history of artistic and philosophical expression, one concept rises to the surface, especially in works that are particularly influential or have a great deal of longevity. From “Strawberry Fields Forever” to Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream, to Descartes’ assertion that “I think, therefore I am” to Bill Hicks’ great “Life Is A Ride” speech, and even in children’s nursery rhymes—life is but a dream. A powerful dream, and one containing an infinite number of lessons for us—but a dream nonetheless.

After all, if everything—Atlantis, Luke Skywalker, your neighbor Bill—is as real as everything else, then what is reality but what we perceive? And what is our perception, if not our creation?

I know that we have to process a lot here, but do keep in mind that there are almost certainly billions of versions of you mulling over the answer to this question; and that given billions of chances to find the answer, one of your versions eventually will—as will we all.

You might as well visit Floorwalker’s blog and follow him on Twitter, since multiple versions of you are doing those things already.