Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Lesser-Known Events in Early American History

“History is a relentless master. It has no present, only the past rushing into the future.”—John F. Kennedy. Some past incidents are swallowed by history’s relentless march forward and are forgotten or become obscure footnotes, which doesn’t mean they aren’t interesting or important. Here are 10 events in early America that often go unmentioned in school. These items include scandal, sex, and violence—just the way we like our history.

“From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli…” Sound familiar? The line about Tripoli in the U.S. Marine Corps hymn commemorates an action in 1805—the Battle of Derna—occurring during the First Barbary Coast War when the fledging American government had to take on the pirates of the Mediterranean. Tripoli, Algiers, Morocco, and Tunis were North African states on the infamous Barbary Coast, long considered a haven for pirates who preyed primarily on merchant ships.

Prior to America achieving independence from Britain, the colonists’ ships were protected by the Royal Navy. During the war, a treaty with France ensured the safety of American merchants. After the war, French protection ceased. In 1784, the Continental Congress solved the problem of the pirates in the same way as every other independent nation: bribery. Basically, the Barbary pirates ran a global protection scheme and the American government had to pay to keep its citizens and their vessels safe.

Some members of Congress like Thomas Jefferson believed paying the pirates would only lead to more demands, but an annual tribute and exorbitant ransoms for captured sailors continued since that was considered cheaper than all-out war until Jefferson became President. He refused to pay tribute directly to the Pasha of Tripoli in 1801, and the Pasha declared war on the United States.

After 4 years of conflict with wins and losses on all sides, in 1805 the Battle of Derna in Tripoli—memorialized in the hymn mentioned above—settled matters to a certain degree, but America still had to pay ransom for hostages taken by the pirates. It wouldn’t be until 1815 that all tribute ceased to be paid by the American government.

Millions of acres of prime real estate. Millions of dollars at stake. Politics, greedy businesses, bribery and corruption. Sound like an episode of a TV drama? A modern political conspiracy? Nope, it’s the late 18th century’s Yazoo Land Fraud scandal.

Right after the Revolutionary War, state boundaries weren’t quite fixed. Georgia claimed land as far west as the Mississippi River, biting off a little more than they could metaphorically chew. The frontier territory, called the Yazoo lands after a river, was already home to Cherokee, Creek, and other tribes (and is now part of Alabama and Mississippi). The lands were untamed, difficult to develop or defend, and twice Georgia tried to cede the territory to the federal government to no avail. The Yazoo lands seemed like a big white elephant nobody wanted … except greedy land speculators.

From the 1780s, companies lobbied state legislators with proposal after proposal for establishing settlements in the Yazoo lands, few of which came to fruition. Speculators continuing bombarding the state legislature, sweetening the pressure with bribes like company stock. Other influential men were bought. Finally, in 1795 a law was passed essentially allowing four land speculation companies to purchase 35 million acres of the territory for less than 2 cents an acre—even adjusted to modern prices, that’s suspiciously cheap. The land was sold for huge profits to other speculators or pioneers looking for a homestead to settle.

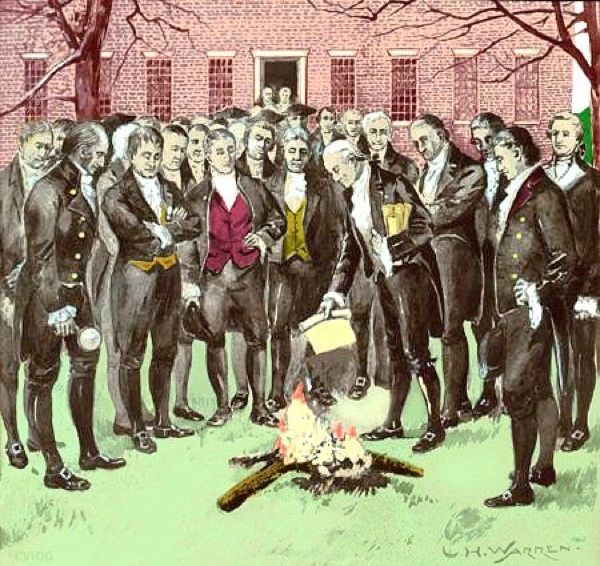

But all did not go smoothly. When news broke about the corruption surrounding the new law and the Yazoo lands, Georgians were furious. The anti-Yazooites gained political power and eventually oversaw the law rescinded and the sale overturned, even going so far as to arrange a public burning of the law and its records. In 1802, the lands were sold to the federal government for $1.25 million, but claims for compensation from losers in the land fraud continued to plague the court systems until 1814.

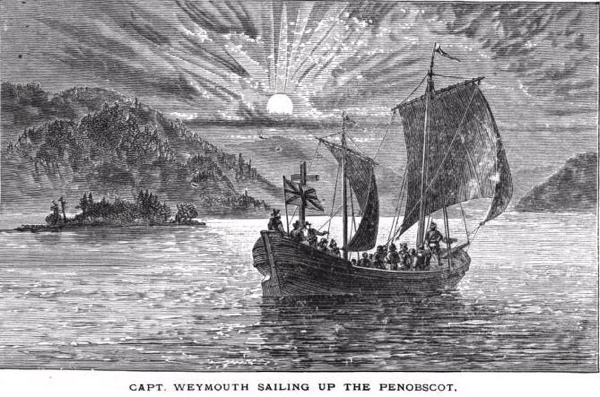

George Weymouth, an Englishman and captain of the ship Archangel, sailed his vessel from England to America—specifically Maine, near Cape Cod—while searching for the mythical northwest passage to India in 1605. Or so he said, but it’s also believed his voyage had more than one purpose: to spy on the French and their new colony in Nova Scotia, and try to settle English dissident (Catholic) colonists in prime locations in the New World.

George Weymouth, an Englishman and captain of the ship Archangel, sailed his vessel from England to America—specifically Maine, near Cape Cod—while searching for the mythical northwest passage to India in 1605. Or so he said, but it’s also believed his voyage had more than one purpose: to spy on the French and their new colony in Nova Scotia, and try to settle English dissident (Catholic) colonists in prime locations in the New World.

After some exploration, Weymouth and his crew made contact with local natives, who were friendly and offered them hospitality and gifts. However, the good neighborly treatment clearly wasn’t enough for Weymouth, who decided that the perfect thing to take back to England would be some samples of indigenous life, namely the natives themselves—for the advancement of scientific knowledge, of course.

Through various deceptions, the treacherous Weymouth pretended to befriend several young native men, then lured or violently captured five of them and took them aboard his ship by force. He promptly sailed home to England with his prizes. Three of the kidnap victims were given to Sir Fernando Gorges, a sponsor of Weymouth’s expedition. The other two were turned over to Sir John Popham, the Chief Justice of England.

Unlike Weymouth, Popham and Gorges treated their native captives with kindness. Later, Gorges sent his three new English speaking friends back to their American homeland. As an interesting side note, one of the natives who returned may have been the famous Squanto, who met the Pilgrims when they first arrived on America’s shores—and while this was purportedly Squanto’s first kidnapping, it wasn’t his last. He’d suffer abduction and slavery three more times before the Pilgrims showed up.

When the French controlled the Gulf of Mexico territory containing Louisiana, they had a problem—too many men. The male settlers included soldiers, farmers, and tradesmen. Valuable assets, of course, but as all governments of the time understood, a really successful and lucrative colony needed families, not just single men. To do that, the men needed wives. It comes as no surprise that most men involved eagerly agreed with the idea.

However, finding ladies willing to marry a stranger and endure the rough frontier with their husbands for the rest of their lives wasn’t easy. Beginning in 1704, the Compagnie des Indes (Company of the Indies) which held the monopoly on trade in the area decided to send 20 young and virtuous French women aged 14-18 to Louisiana via the ship Le Pélican. These “Pelican girls” were snapped up by men desperate for marital bliss and/or the generous dowry and other benefits subsidized by the King.

Other shipments of volunteer brides occurred periodically. Many were orphans, some less than respectable from houses of correction. Perhaps the most famous were the seventy-eight upstanding “casket girls” or filles à la cassette, named after the small caskets (like suitcases) that carried their belongings. Upon arrival, they were popped into the newly built Ursuline convent in New Orleans and supervised by the nuns until they found husbands. Today, claiming a “casket girl” as an ancestress is a matter of pride for native Louisianans.

Despite the pressure put on new arrivals, not all girls chose to marry. Some entered convents, received the education denied their secular sisters, and became nuns. But most women married, many were widowed, and if they survived the hardships of childbirth and frontier life, they often prospered due to generous inheritance laws.

Most people have heard of the Scotsman Captain William Kidd and his exploits along the eastern seaboard of America. Fewer people know about Joseph Bradish, a home-grown pirate born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1672. His connection to Kidd came at the end of his life before facing the Execution Dock at Wapping in London.

Bradish was a young man when he worked as a boatswain’s mate aboard Adventure, a British 400-ton “interloper”—a ship interfering in trade monopolies—from London bound for the island of Borneo. During the voyage, he incited the crew to mutiny, marooned the captain and officers, and took over the roles of navigator and captain himself. With his newly formed pirate band, he enjoyed “some adventuring in Eastern seas.” While details are sketchy, it’s believed he seized valuable prizes of gold and jewels as well as Adventure’s cargo of lead, Spanish gold, opium, and other goods.

He sailed to Long Island in America in late 1698 or early 1699 and scuttled the ship. However, he was unable to buy a replacement vessel and settled on a small sloop. After seeing the majority of his crew scattered along the coast (and according to legend, burying treasures at Montauk Point and Block Island), he entered Boston. Unfortunately, Dame Fortune wasn’t on his side. Bradish was promptly arrested, but that isn’t the end of his tale.

The pirate captain’s luck hadn’t entirely run out. The local jailer, Caleb Ray, was a relation of Bradish’s and helped him escape (although in later accounts, the serving girl got the blame). An enraged governor ordered a search. Bradish was recaptured and shipped to England with William Kidd as his cellmate. Both men were executed.

In Queen Anne’s County, Maryland, a prosperous farmer named Thomas Harris enjoyed a long-term relationship with Ann Goldsborough, though the lady wasn’t his wife. They had four children out of wedlock. Harris’ unexpected death not only shattered the life he’d built with his family, it provided the catalyst for one of America’s strangest court cases.

In his will, Thomas Harris instructed his brother James to act as executor, sell the property, and divide the proceeds between his four children. He also had a conversation with James about his wishes prior to his death, but James had other ideas. He cast doubt on the will, ignored his deceased brother, and kept the money for himself.

A few months after Thomas Harris’ death, William Briggs—his best friend since boyhood and a respected Revolutionary War veteran—happened to ride past the graveyard where Harris was buried. His horse (which once belonged to Harris) suddenly wheeled around. Briggs saw an apparition of Harris in a blue coat, the same he’d worn in life.

The apparition vanished, but that wasn’t the only time Briggs would be visited by his best friend’s spirit. After several other sightings and some phenomena including being struck in the face by a mysterious force and having both his eyes blackened, Briggs finally learned what Thomas Harris wanted. The ghost told him about the will and James Harris’ betrayal. To make sure James believed the message came from his dead brother, Briggs was given several details about the conversation no one but Thomas and James could have known.

Briggs went to James with his story. The details were correct. James had a change of heart and promised to fulfill the terms of his brother’s will, but before he could make the arrangements, he died. His widow, Mary, refused to acknowledge James’ promise and claimed all her husband’s property as her own.

Years later, Thomas Harris’ illegitimate children filed a lawsuit against Mary. The key witness and main evidence in the trial was William Briggs, who testified in detail about seeing and speaking to his friend’s ghost. Although the defense attempted to refute Briggs’ testimony, and the outcome of the case hasn’t been discovered yet in Maryland’s archives, the judge did officially acknowledge the existence of ghosts in court.

Thomas Granger worked as a servant for Love Brewster in the Plymouth colony in Duxbury, Massachusetts. In 1642, at about 16 or 17 years of age, Granger was accused of violating statutes based in Biblical law, specifically Leviticus 20:15—“And if a man lie with a beast, he shall surely be put to death: and ye shall slay the beast.” The Massachusetts area was experiencing something of a bestiality panic at the time, so was Granger a pervert, or was this just a prank that got out of hand due to hysteria? Either way, he lost his life.

Thomas Granger worked as a servant for Love Brewster in the Plymouth colony in Duxbury, Massachusetts. In 1642, at about 16 or 17 years of age, Granger was accused of violating statutes based in Biblical law, specifically Leviticus 20:15—“And if a man lie with a beast, he shall surely be put to death: and ye shall slay the beast.” The Massachusetts area was experiencing something of a bestiality panic at the time, so was Granger a pervert, or was this just a prank that got out of hand due to hysteria? Either way, he lost his life.

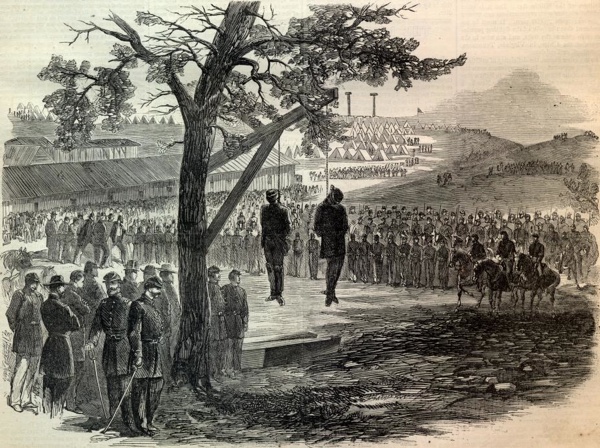

Granger was caught performing lewd acts with a mare (the chronicler, William Bradford, governor of the colony, protected the delicate sensibilities of future generations by refusing to detail the acts in question). When confronted, Granger at first denied the accusation. However, it wasn’t long before he not only confessed to the magistrates to having done the deed with the mare numerous times, he also named a cow, 2 goats, 5 sheep, 2 calves, and a turkey as the objects of his past attentions.

The confession was enough to earn him the death penalty from a jury. A parade of sheep was brought into the courtroom so Granger could identify which ones he’d abused. All the animals he’d named were killed while he watched. The law required no part of the “unclean” animals be used, so a pit was dug and the carcasses buried. Following the slaughter, Granger was executed for committing “sodomy”—one of the death penalty crimes on the books. He became the youngest person in America to be hanged under these statutes.

Despite his age, Granger was survived by a wife and two children.

The poet Charles Olson wrote about Thomas Granger in 1947.

During the conflict, what did the British do with prisoners of war? Put them in prisons, of course, but these jails were soon overcrowded. Hulks—ships in too bad shape to see service—were anchored in harbors to serve as convenient places of confinement for POWs and regular criminals. These British prisons were infamous for the appalling conditions which included starvation, poor sanitation, and disease. The man in charge of prisoners in New York City was the cruel and petty Provost Marshal, William Cunningham.

Following surrender, British forces had to leave New York City during Evacuation Day in late September 1783. To signal the end of the occupation and indicate the last British solider had left aboard ship, it was agreed the British commander would fire a cannon at 1 o’clock. Jubilant, the newly independent Americans didn’t wait—they celebrated by knocking over a statue of King George III and flying the American flag. One such patriot was Mrs. Day, who ran Day’s Tavern located at 128th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue.

The very unpopular Provost Marshal Cunningham, infuriated by the displays ahead of the official time, ended up in front of Day’s Tavern where a rebel flag proudly flew. He tried to tear the flag from the pole, but Mrs. Day ran out of her drinking establishment toting a broom to defend her property. According to the story, she hit him with the broom with such force, powder flew off his wig and his nose was bloodied.

True or wishful thinking? The jury’s out, although Cunningham’s existence and his mistreatment of prisoners is not disputed. If Mrs. Day did, indeed, assault one of the most hated men in NYC, she certainly struck the last blow in the Revolutionary War.

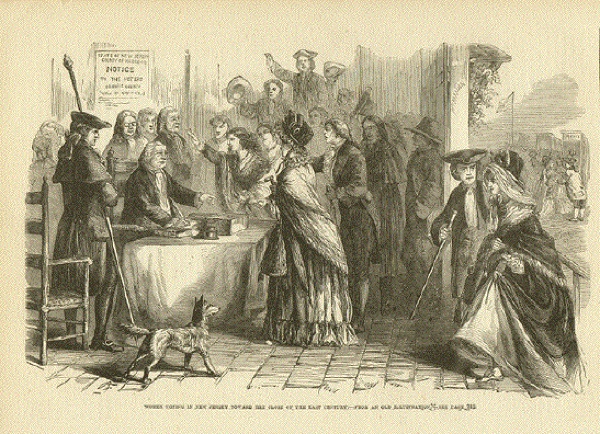

The framers of the U.S. Constitution left it up to the individual states to determine their own voter qualifications. Some states imposed religious requirements on their citizens (although this pretty much ended by 1790). Others decided who had the right to vote based on property ownership or tax payments. And then there was New Jersey.

The men who drew up the state of New Jersey’s Constitution didn’t have a problem with women voters provided they met the rather low property ownership requirement. When every other new state deliberately left women out of the voting equation, New Jersey legislators embraced the radical idea that not only ladies should be members of the political community, but free blacks and aliens (non citizens), too.

This led to an unusual circumstance. According to the laws of the time, when a woman married, all her property automatically became her husband’s. Since a married woman owned nothing of her own in a legal sense, wives couldn’t vote as they no longer met the property ownership requirement. However, no such bar existed for single women and widows.

Did women cast ballots in New Jersey elections? From 1797, records clearly show the names of women on the polls. In fact, the female vote was courted in some cases by the Democratic-Republican and Federalist parties. Did women vote in great numbers? Not really. And the enfranchisement of women remained controversial and a subject of great debate in the state. Women, it was argued, were too delicate to make political decisions, unfit by nature to involve themselves in men’s business, and were too busy raising children anyway.

Eventually, the naysayers got their way. New Jersey rescinded women’s right to vote in 1807. Ladies wouldn’t get it back until the state ratified the 19th Amendment in 1920.

The connection may not seem obvious, but Nantucket whalers played a pivotal role in the American fight for independence, helping bring about American victory over the British, ultimately ending the Revolutionary War with General Cornwallis’ surrender.

One of the best kept secrets of the war was made earlier by curious New England whalers and merchants, who observed whale migrations in the Atlantic. They found the Gulf Stream, a strong ocean current first recorded by John White, governor of Virginia’s Roanoke colony, in 1506. Through years of trial and error, the whalers gained a good working knowledge of the current. Their observations caught the attention of Benjamin Franklin, who undertook a scientific journey to verify the claims and satisfy his own curiosity.

Why wasn’t the Gulf Stream generally known to all shipmasters? Because shipping routes were well established and had been determined by trained navigators, a conservative bunch who didn’t tend to share their information. The Gulf Stream was important since using it shaved off time from the journey between North America and Europe. The secret charts made by Franklin gave the American rebels an advantage over the British.

In 1781, the Continental Congress anticipated the arrival of their ally, Admiral Henri de Grasse, and a fleet of 173 French ships. So did British admiral Sir George Rodney in the Caribbean and his subordinate, Admiral Alexander Hood, who waited in the Leeward Islands. In France, British spies sent a report about De Grasse’s armada and its destination to Rodney via a fast cutter, but the cutter’s captain knew nothing about the Gulf Stream. By the time the message made it across the Atlantic, De Grasse’s fleet had already defeated Hood.

Had Rodney received the warning in time, he would probably have supported Hood and perhaps defeated De Grasse, which means the Battle of Yorktown—which gave America a decisive victory against the British thanks in part to the French troops brought by De Grasse—wouldn’t have happened or may have had a different outcome.