Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Terrifying Prehistoric Relatives of Normal Animals

Today, man is the dominant predator on the planet. Yet we have occupied this position for a relatively short period of time—the earliest known man, Homo habilis, first appeared around 2.3 million years ago.

Although we dominate the animals of today, many of these animals have extinct relatives that were a lot larger and more vicious than what we’re familiar with. These animal ancestors look like creatures straight out of our worst nightmares. The frightening aspect is that if mankind vanishes—or merely loses its dominance—these creatures, or something like them, could potentially return again to existence.

Today, sloths are tree-climbing, slow, and non-threatening animals that reside in the Amazon. Their ancestors were the complete opposite. During the Pliocene era, Megatherium was a giant ground sloth found in South America; it weighed up to four tons and was twenty feet (6m) in length from head to tail.

Although it primarily moved on four legs, footprints show that it was capable of being bipedal, in order to reach leaves from the tallest trees. It was the size of a modern day elephant, and still wasn’t the largest animal in its habitat!

Archeologists theorize that Megatherium was a scavenger, and would steal dead carcasses from other carnivores. Megatherium was also one of the last giant Ice Age mammals to disappear. Their remains appear in the fossil record as recently as the Holocene, the period that saw the rise of mankind. This makes man the most likely culprit in the extinction of Megatherium.

When we think of a giant ape we generally think of the fictional King Kong—but colossal apes really did exist, long ago. Gigantopithecus was an ape that existed from roughly nine million to a hundred thousand years ago—placing it in the same time period as several hominid species.

The fossil record suggests that individuals of the species Gigantopithecus were the largest apes to ever exist, standing at almost ten feet (3m) tall, and weighing twelve hundred pounds (540kg). Scientists have not been able to determine the cause of extinction for this large ape. However, some crypto-zoologists theorize that “sightings” of Big Foot and Yeti may relate to a lost generation of gigantopithecus.

Dunkleosteus was the largest of the prehistoric fish Placodermi. Its head and thorax were covered by articulated armored plates. Instead of teeth, these fish possessed two pairs of sharp bony plates, which formed a beak-like structure.

Dunkleosteus likely attacked other related placoderms that had the same kind of bony plates for protection; their jaws had enough driving power to cut and break through armored prey. One of the largest known specimens found was thirty-three feet (10m) long and weighed four tons—making it one fish that you would not want to catch on a reel and rod!

This fish was anything but picky with its food; it ate fish, sharks and even its own kind. But it seems to have suffered from indigestion, as its fossils are often associated with regurgitated, semi-digested remains of fish. Scientists at the University of Chicago concluded that dunkleosteus had the second most powerful bite of any fish. These giant armored fish became extinct during the transition from Devonian to the Carboniferous periods.

Most flightless birds today—consider the ostrich or the penguin, for example—are harmless to human beings; however, there was once a flightless bird that terrorized the earth.

Phorusrhacidae, also known as “terror birds,” were a species of carnivorous and flightless birds that were the largest species of predators in South America, between sixty-two million and two million years ago. They were roughly three to ten feet (1-3m) tall. The terror bird’s prey of choice were small mammals . . . and, incidentally, horses. They used their massive beaks to kill in two ways; by picking up small prey and slamming it to the ground, or by precision strikes on critical body parts.

Although archeologists have not yet fully determined the reason this species went extinct, the last of its fossils appear around the same time as the first humans.

Birds of prey have always left an imprint on the human psyche; luckily, we are far bigger than the largest eagle. That said, birds of prey that were large enough to hunt a human meal once existed.

The Haast’s eagle once lived on the South Island of New Zealand, and was the largest eagle known to exist, weighing up to thirty-six pounds (16.5kg) with a ten-foot (3m) wingspan. Its prey consisted of the moa, three-hundred-pound flightless birds unable to defend themselves from the striking force and speed of these eagles, which reached speeds of up to fifty miles (8km) per hour.

Legends from early settlers and native Maori had it that these eagles could pick up and devour small children. But early human settlers in New Zealand preyed heavily on large flightless birds, including all moa species—eventually hunting them to extinction. The loss of its natural prey caused the Haast’s eagle to become extinct around fourteen hundred years ago, when its natural food source was depleted.

Today, the Komodo dragon is a fearsome reptile and the largest lizard on the planet—but its would have been dwarfed by its ancient ancestors. The megalania, also known as the “Giant Ripper Lizard”, was a very large monitor lizard. The exact proportions of this creature have been debated, but the most recent research revealed that the megalania’s length was around twenty-three feet (7m), and that it weighed approximately thirteen to fourteen hundred pounds (600-620kg), making it the largest terrestrial lizard known to have existed.

Its diet consisted of marsupials, such as giant kangaroos and wombats. Megalania belongs to the clade toxicofera, possessing toxin-secreting oral glands—making this lizard the largest venomous vertebrate known to have existed. Although we couldn’t imagine a lizard of this size roaming in the Outback, the first Aboriginal settlers of Australia may have encountered living megalanias. The species most likely went extinct when early settlers hunted the megalania’s food sources.

Bears are some of the largest mammals on Earth, with the polar bear even holding the title for the largest of all carnivores on land. Arctodus—also known as the short-faced bear—lived in North America during the Pleistocene. The short-faced bear weighed about one ton (900kg), and when standing on its hind legs it reached a height of fifteen feet (4.6m), making the short-faced bear the largest mammalian predator that ever existed.

Although the short-faced bear was a very large carnivore, archeologists have discovered that it was actually a scavenger. Being a scavenger, however, was not at all a bad thing—especially when you’re fighting saber-tooth cats and wolves for a meal. Like many other large animals of the Pleistocene, the short-faced bear lost much of its food source with the arrival of humans.

Modern-day crocodiles are living relics of the dinosaurs—but there was a time when crocodiles hunted and ate said dinosaurs. Deinosuchus is an extinct species related to alligators and crocodiles, which lived during the Cretaceous Period. The name deinosuchus translates to “terrible crocodile” in Greek.

This crocodile was far larger than any modern version, measuring up to thirty-nine feet (12m) and weighting almost ten tons. In its overall appearance, it was fairly similar to its smaller relatives, with large robust teeth built for crushing, and a back covered with armored bone plates.

Deinosuchus’ main prey were large dinosaurs (how many can make that claim?) in addition to sea turtles, fish and other hapless victims. Potential proof of the danger of deinosuchus comes from the fossils of an albertosaurus. These specimens bore tooth marks from both deinosuchus and Tyrannosaurus Rex, which means that there is a great chance these two fierce predators once engaged in colossal battles.

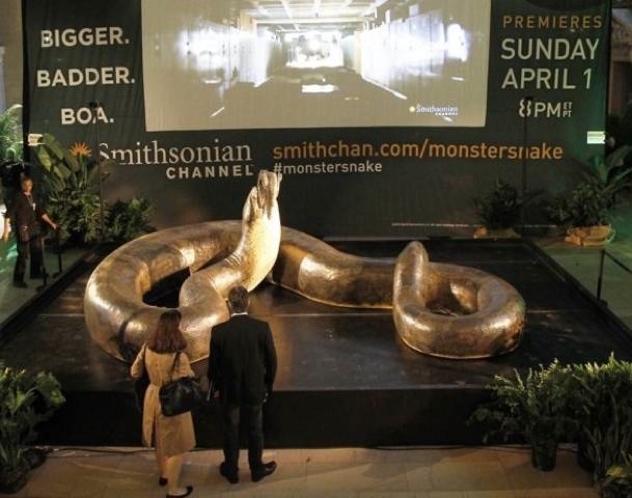

No creature invokes more fear in the human psyche than snakes. Today the largest snake is the Reticulated Python, with an average growth of twenty-three feet (7m).

In 2009, archeologists made a shocking discovery in Columbia; by comparing shapes and sizes of its fossilized vertebrae to those of modern snakes, they estimated that the ancient snakes, titanoboa, reached a maximum length of forty to fifty feet (12-15m) and weighed up to 2,500 pounds—making it the largest snake to ever slide around the planet. Because it’s a recent discovery, little is known about titanoboa; what is known is that a fifty-foot snake would scare the daylights out of anybody, phobia or not.

Before 1975, most humans’ animal phobias came primarily from snakes and spiders. That all changed when the film Jaws was released; the film’s antagonist was a (fake) great white shark, which ended up scaring many people away from entering the ocean. Today, the largest great white sharks are usually twenty feet (6m) in length and weigh five thousand pounds (2,275kg). However, there was once a shark that was double the size of the largest modern great white sharks.

Megaladon—meaning “big tooth”—was a shark that lived approximately twenty-eight to 1.5 million years ago. Everything about the megaladon was mega: its teeth were 7.1 inches (18cm); and fossil remains suggest that this giant shark reached a maximum length of 52-67 feet (16-20m). While today great white sharks prey on seals, the megaladon’s meal of choice was whales. Scientists hypothesize that the species went extinct due to oceanic cooling, sea level drops, and a decline in food supply. If the megaladon were still alive, there is a great chance that man would have been a landlocked species. Still, in the giant oceans there may be a titanic great white shark lurking in the abyss—so there’s always a chance that something like the megaladon could return to the world.

Phil Moore is an historian, writer and filmmaker, who looks to spark intriguing and scholarly debates about all aspects of life. None of his lists or works of art are meant to offend, but merely for discussion.