History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Reasons You Aren’t In Control Of Your Own Decisions

If there’s anything in the world that should be ours and ours alone, it should be our thoughts. They’re in our heads, after all, and if there’s any place that should be sacred and private, it’s there. Turns out that’s not exactly true, though, and there are so many outside influences shaping your thoughts that you might be left wondering just how many of your emotions, beliefs, and feelings are actually yours.

10 Your News Feed Can Change Your Mood

For all its popularity, Facebook isn’t without its share of scandals. In the latest one, details came out of an experiment conducted on 700,000 Facebook users over the period of a single week in 2012. News feeds were manipulated to contain positive or negative news and content, then users were monitored to see if the change made them use more positive or negative words in their status updates. And it worked—people’s status updates showed a change in emotion that went along with the kind of news that they were exposed to. The term used was “emotional contagion,” and it confirms something pretty frightening.

According to the study, people don’t even have to be physically around another person in a bad mood to absorb the negativity into themselves—negativity can be “caught” just from looking at a computer screen. There doesn’t need to be a personal, emotional connection for emotional contagion to happen. Not surprisingly, the study has brought up a number of disturbing questions, and it’s now being investigated by organizations like the Information Commissioner’s Office in Dublin. Those questioning the ethics of the study state that it’s nothing less than psychological manipulation. As if that’s not shady enough, Facebook users were unaware that they were having their emotions and moods manipulated through another party controlling just what was popping up in their news feeds.

9 Facts In Story Form Are Much More Effective

You’re sitting in a sales meeting, and you’re presented with a first-person story about how the boss locked down the first tough sale of his career. You’re also presented with a bullet-point list of all sorts of statistics, facts, and numbers. Which are you more likely to remember? Even if the bullet-point list contains all the same information as the story, you’ll be able to remember more details more accurately from the story. That’s because storytelling is an insanely powerful thing, and there’s some pretty amazing science behind just why we find a story a much more interesting way to receive information.

When we’re looking at a list, the parts of the brain called Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area are activated and receive the information—and that’s all that happens. A good story activates all different parts of the brain, from the parts that interpret language to the parts that relate to our own sensory perception. Storytelling establishes something that a plain list doesn’t—a connection with the speaker. And that connection can make all the difference in the world when it comes to remembering what a presentation was about. More than that, we become invested in the story. We see characters instead of dry facts, and we want to know how it all ends.

This craving for closure has another effect, too: It lowers some of our inhibitions. We become less critical of the information, we allow for improbabilities for the sake of storytelling, and we suspend skepticism without even realizing that we’re doing it. If it’s a good story, we’ll excuse a little bit more. If it’s a dry assortment of facts, we’re left picking it apart if only for some way to entertain the parts of our brain that are getting bored. So great is the power of storytelling that some researchers put forth the idea that fiction is more effective at completely changing our views and belief systems than data dumps of scientific facts.

8 Subliminal Messaging Works

In the 1950s, a man named James Vicary was the first to experiment with subliminal messaging, flashing “Drink Coca-Cola” on movie screens while films were playing in a few theaters. While he claimed that it worked and that sales increased in those theaters, science has long been doubtful about just how effective the use of subliminal messaging is. Researchers at the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research have shown that, in spite of the later finding that Vicary’s results were bogus, subliminal messaging does work.

Volunteers in the Netherlands study were exposed to the subliminal messages “drinking” and “thirsty,” and then researchers measured how likely the volunteers were to accept a drink. Variations in the study led researchers to the conclusion that subliminal messaging really only works as long as a handful of conditions are present: There needs to be a pleasurable reward for giving in to the subliminal message, thoughts need to be planted ahead of the chance for fulfillment, and there needs to be a pre-existing association with the reward that makes it pleasant. Other studies, including one by University College London, supports the idea that the human brain is subconsciously aware of things that happen too fast for us to consciously register—especially negative emotions. Volunteers in a study were exposed to a variety of subliminal messages, then asked to indicate whether the message was neutral or emotionally charged. Volunteers were surprisingly accurate, and they were most accurate when the words were negative.

7 We’re Programmed To Be Gullible—Especially If We’re Smart

It seems contradictory, we know. But how many times have we heard of the most intelligent among the human population being taken in by some scam that, in retrospect, seems so obviously fake that it’s painful? Today, we cringe at the gullibility of an entire army dragging the gift of a Trojan Horse inside their gates, and we shake our heads at people who lost millions investing in the welfare of a Nigerian prince. But psychologists suggest that we can’t help but believe the hoaxes. In fact, the smarter we are, the more gullible we might be, and many hoaxes are designed to play off these weaknesses in our defense system.

Part of it has something to do with ego; the smarter we are, the less likely we are to believe that we can be fooled. We assume we’ll see it coming a mile away, and that overconfidence means we might just outright miss it instead. Another part of it is that we’re programmed to trust sources that have always been reliable, and put our faith in people with titles like “Professor” and “Doctor”—that’s why we believe the priest who found Heaven on Earth or the astronomer who told us gravity was going to go away for a bit.

There’s also the idea that there are different types of intelligence—the intelligence that has allowed a person to create a successful career for themselves might not be the same type of intelligence that allows them to see through a scam. According to psychologist and author Stephen Greenspan, intelligence can often bow in the face of the social pressure exploited by many scams, or when the person is confronted with the possibility of an outcome that either seems too good to be true or just modest enough to be reasonable. Intelligence can also lose out to another factor: kindness. No matter how smart a person may be, they also might be too kind to outright shut down a personable scam artist, or decline an offer after they’ve been sitting in a meeting for several hours. And intelligence is certainly no match for emotion, either, especially the emotion that comes with promises of riches.

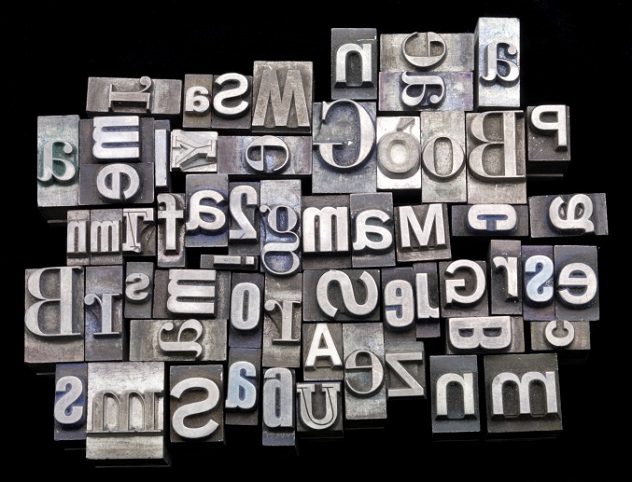

6 We’ll Believe Some Fonts Over Others

Comic Sans. The mere mention of it is enough to conjure images of a child’s birthday party invitation or an announcement for the local garden club. It’s not used in academic journals or in reputable newspapers, and there’s a reason for that (aside from aesthetics). The font used for any given news story, blog, or essay influences how likely we are to believe it. In 2012, New York Times columnist Errol Morris tried an experiment. He took a passage from a book on the likelihood of a cataclysmic event happening on Earth, had people read it, and then asked how many of them believed the passage (under the guise of an optimism vs. pessimism questionnaire). The questionnaire was programmed to display in one of six random fonts: Trebuchet, Computer Modern, Baskerville, Georgia, Comic Sans, or Helvetica. At the end of the sample period, 45,524 people had taken the quiz.

Numbers and data were crunched, and in the end, Baskerville had about a 1.5 percent advantage over the other fonts in getting people to agree with the passage. It also out-performed other fonts in terms of strength of agreement. The quiz was weighted (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”), and once those numbers were factored in, it was found that Baskerville also had the highest rate of agreement and the lowest rate of disagreement. And while 1.5 percent might not seem like much, the results could be potentially staggering when they’re viewed in the context of elections or sales. The psychologists that analyzed the study, including Cornell University’s David Dunning, believe that it happens because we lend more credibility to something that looks formal, and we unconsciously process that information. Or, in the case of people around the world flaming CERN for releasing earth-shattering news about the Higgs boson particle in Comic Sans, sometimes it can be a conscious thing, too.

5 We’re More Likely To Commit A Crime In A Questionable Neighborhood

No matter how moral you think you are, it turns out that you can be influenced by your surroundings into some less-than-honorable acts. It’s called the “Broken Windows” theory, developed by psychologists James Wilson and George Kelling. The theory states that the more run-down an area is, the more lawless it will be perceived as being, and, in turn, the more likely people are to assume that breaking the law is at least somewhat acceptable. An experiment conducted in the Netherlands supported the idea, finding that people were twice as likely to take money out of a mailbox if there were signs of neglect in the surrounding property.

Other studies, such as one done by a Stanford psychologist in Palo Alto, California and the Bronx in New York, also substantiated the theory. Untouched cars were left alone, but a car that had already been vandalized and left to sit was stripped within a day. Even the car that had sat untouched and undisturbed was destroyed within hours after researchers smashed it once with a sledgehammer. As a result of the theory, many police departments have made literally cleaning up the streets a part of their duties. In many places, increasing foot patrols has made a significant difference, not so much in crime rate, but in how safe people feel.

4 Our Plate Size Changes How We Eat

It’s called the Delboeuf illusion, and it’s been well documented since 1865. The principle is most effectively measured now in relationship to how much we pile on our plates in a single serving. Take two portions of equal size. Put one on a large plate and one on a small plate, and the serving on the small plate will look bigger. When studies have asked people to portion out a serving size for themselves, those who are given bigger plates will pile on 13 percent more food on average than those who are given smaller plates. The same thing happens when we’re pouring ourselves a drink. Pour yourself a shot, then try to pour the same amount of liquid into a pint glass—it’s difficult to do, because our brains can’t overcome the illusion of relative size and amounts. And it’s extra difficult for the human brain to judge vertical lengths; even longtime bartenders will generally think that a narrow, tall glass holds more liquid than it actually does. Interestingly, the size of the average dinner plate in America has increased almost 25 percent in the last century, coinciding with a slowly progressing obesity epidemic.

3 Colors Can Change Everything

Interior decorators say that we’re supposed to choose room colors based on the feelings we want the room to have, but there’s considerably more to it than that. According to an article in Forbes magazine, business owners can influence a lot more than the moods of their customers by careful color selection. Warm colors, such as browns and reds, can actually make a person feel warmer, while cool colors like blues can make them feel cooler—which can actually mean saving on heating and cooling bills. And colors can cause the above-mentioned Delboeuf’s illusion as well. When plate color contrasts with food color, you’re more likely to think you’re eating more and, in turn, take smaller portion sizes. When the plates are the same color as the food, you’ll eat more.

It’s also been hypothesized that lighting color can have an even more drastic effect on influencing people’s actions. In 2000, the city of Glasgow, Scotland changed some of their streetlights to emit blue light, a color that’s traditionally been thought to have a calming effect. According to city officials, crime in the areas of the blue lights dropped dramatically. Japan followed suit. Crime was reported down 9 percent after blue lighting was installed in Nara, and the Keihin Electric Express Railway Company later installed blue lights on a railway platform that was a notorious suicide spot. According to the station, there was a significant reduction in suicide attempts at the Gumyoji Station after the lighting was installed.

2 Advertising Works, Even When We Don’t Think It Does

Of course advertising works: Companies wouldn’t spend huge amounts of money on it if it didn’t. They also know what works best, and that’s why we see so many random commercials with messages seemingly unrelated to the product they’re trying to sell. A study done by George Washington University and the University of California, Los Angeles presented volunteers with advertisements that used actual facts about a product as well as commercials that used feel-good ideas or random images that seemed to have nothing to do with the actual product. When viewing the list of facts, the amount of electrical activity in the brain was significantly lower than it was when the person was looking at the advertisement with more fun imagery. Feel-good imagery, no matter how nonsensical it might be, ended up eliciting more of a response from the brains of the target audience.

Advertising is also designed to work even if you fast-forward through most of it. With the invention of digital video recorders, it was originally thought that television ads were going to lose their effectiveness because people were skipping over them. Studies by the Harvard Business Review have shown that’s absolutely not true—while you might think you’re skipping the ads, you’re still being influenced by them. In order to fast-forward, you need to be looking at the screen to know when to stop again. And that means you’re paying attention to the advertisement, even more than you would be if you simply left the room or did something else during the break. When you’re fast-forwarding, your brain sees a Big Mac flash up on the screen, and even though you’re not watching the whole thing, thoughts of a Big Mac are still planted in your mind. And because we’re likely to still watch television shows as they’re broadcast, we still have some exposure to advertisements. Once we’ve seen something once, our brains can recognize it from seeing only snippets as we think we’re skipping over it. Nielsen ratings from 2009 found that only about 68 percent of commercials are fast-forwarded through, leaving plenty of raw advertising materials to be stored in our brains for a later nudge.

1 Some People Physically Can’t Resist Peer Pressure

Peer pressure is more commonly thought of as a bad thing than a good thing. It can be good, encouraging people to learn from each other and explore new ideas and hobbies. Yet the connotation remains bad, and we tend to think of friends encouraging friends to try a new drug or shoplift. And as much as we think we can guard against peer pressure, it’s still an influence, usually without us even realizing it. It turns out that peer pressure taps into a specific part of the brain—the part that signals a reward.

According to a study by Temple University, brain scans conducted on teens who knew their friends were watching them carry out rebellious actions—in this case, running yellow lights in a driving game—show that the act of breaking the law ignites the pleasure and reward centers in the brain. The same study conducted with adults found that there was no corresponding trigger, suggesting that peer pressure is a bigger factor for teens. The trigger happened with the knowledge that someone else was watching; there was no reward center activation when the volunteer was just playing, and there was also no need for the watcher to interact directly with the teen being studied.

It also suggests that when teens are aware that they’re being watched by others, their behavior changes drastically—whether they know it or not. There is a way to help make the brain more prepared to fight the effects of peer pressure, though, and that’s to teach your teen to argue. Teens who are prepped at home to be able to stand up for themselves and express their own opinions are more likely to be able to resist—and recognize—peer pressure.

+ Background Music Affects How Much We Buy

At first listen, the background music that’s being played in a store might seem like an arbitrary choice at best, and certainly one that doesn’t have much of an impact on shoppers. But studies have shown that that’s absolutely not the case—there are a number of different ways that the music being played is changing your behavior. Part of the effect comes from your perception of time. Songs with faster beats and tempos will make you think you’ve spent less time shopping that you actually have, and in turn, you’ll spend more time browsing and finding things to buy. The same thing works when you’re on the phone and on hold—faster songs make people report shorter wait times. Part of the phenomenon is that listening to music, even in the background, takes a little bit of brainpower. That’s less of your brain to focus on how much time you’re spending in the store or on whether or not you should make a purchase, and it makes you more susceptible to the pitch of a salesperson.

Other studies have found that the type of music played also has a significant impact on shopper’s habits. One in particular measured the types of wines that customers bought when different types of music were being played. On days when French music was broadcast, sales for French wines increased. When German music was played? The sales of German wine increased. Interestingly, customers in the study didn’t remember the music at all, and some even denied that it was a factor in the choices that they made, suggesting that music is one of the best types of subliminal messages that can be broadcast.