Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

10 Fascinating Stories From The Oregon Trail

If you’re of a certain age, part of your childhood was spent on the Oregon Trail. Not literally, of course, but figuratively: It was one of the most successful computer games from the early age of computers. The Oregon Trail was written by history teachers looking for a new way to get their students interested in learning about the country’s history. It worked and spawned a huge following. But the game truly only scraped the surface of the fascinating stories that were forged on the real Oregon Trail.

10Wel Mel Ti Tried To Help The Donner Party

The Donner Party is perhaps the most well-known chapter of the Oregon Trail, and it’s one that hasn’t been completely written yet. For decades, it was a bit of a mystery just where the Donner Party’s final camp was. The general location of the camp at Alder Creek was long known, but it was only in 2012 that archaeologists found the exact site of the party’s camp. What they found was pretty incredible: Members of the Donner Party hadn’t been alone—other people had tried to help them. Among the bones that were found at the site were rabbits and deer, but according to all the firsthand accounts of the Donner Party, those animals weren’t eaten by the travelers. Low on ammunition, the members of the party wouldn’t have had the strength to go hunting anyway.

Archaeologists also took another look at some of the stories that have long been passed down through the history of a local Native American tribe, the Wel Mel Ti. These stories describe a group of travelers starving over the long winter months. The Wel Mel Ti tried to help these travelers, leaving everything from rabbits to potatoes at the edge of their camp. They also tell of a deer that the tribe tried to bring to the travelers, but when they got close to the group of starving, terrified settlers, they were shot at. The Wel Mel Ti continued to watch the group as they went on their hunting trips. One day, the tribe saw the travelers eating the remains of those that had died. After that, the Wel Mel Ti avoided going near the camp, fearing for their own lives.

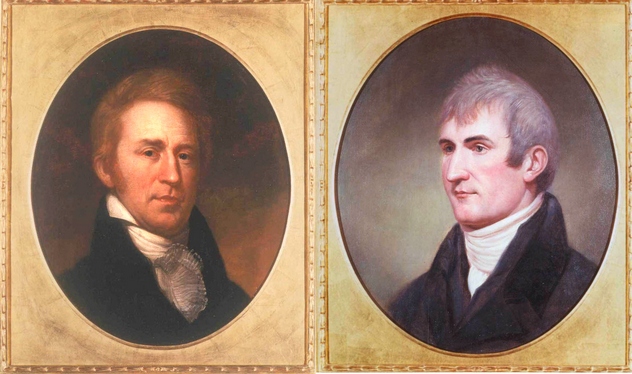

9The Strange Popularity Of Lewis And Clark

According to the popular story, famed explorers Lewis and Clark led an expedition into the untamed wilds of the American West, blazing trails and discovering everything along the way. We’ve talked about how that’s not exactly true, and that leaves the question of just why we’ve put them on such a pedestal.

Lewis and Clark were almost destined to fail before they even set out. Their instructions from Thomas Jefferson were to find the easiest route for people to travel from east to west, but it was an idea that was built on a little bit of faulty logic. Jefferson was convinced that the West was something of a mirror image of the East they already knew. When they didn’t find what he thought they should be looking for, Jefferson went into damage control mode. By the time their findings came out, people were more concerned about the War of 1812 and forgot about the failed exploration.

Another attempt at creating heroes from the failed expedition was made in the 1940s, but again, people were more concerned with war. By the 1960s, though, Lewis and Clark’s writings were published, a four-hour television documentary was made about them, and suddenly, they were heroes. Today, they’re credited with forging the original Oregon Trail through uncharted wilds . . . even though we know that’s not precisely how it happened.

8The Failed Alternative: Bozeman Trail

In 1864, we were very close to a much easier version of the Oregon Trail, at least in the section through Wyoming and Montana. It was easier to travel, there was more water and resources, and it was shorter. There were, however, already people there, and they didn’t take lightly to the hundreds of pioneers that were suddenly on their doorstep. The Cheyenne and Lakota tribes told the pioneers to turn around. While some did, John Bozeman didn’t.

For a time, it looked like there might be a chance of peace. Government officials had gotten as far as arranging to sit down with tribe leaders to discuss peaceful terms. It was about then that the military showed up, with orders to build three forts in the territory that was, theoretically, still under discussion. They also came with a pretty boastful attitude, assured that they’d cut through whoever didn’t let them pass. Understandably, this didn’t go over well.

In 1866, a military contingent that had been out chopping wood was attacked by a small group. Reinforcements—led by the captain that had made the rather uncalled-for, boastful remarks—rode out to support the woodcutting team. The 80 infantrymen and cavalry suddenly found themselves in the middle of a sea of angry native people from all the local tribes, who had effectively gotten together to show the military just what they thought not only of their presence but of their disrespect. The troops were slaughtered, and the military got the point. General Ulysses S. Grant ordered the forts abandoned, and the Bozeman Trail was no longer an option.

7The Port Orford Meteorite

This story is a bit of a strange one. In 1856, Dr. John Evans was out on the Oregon Trail, surveying the territory that would later become the state of Oregon. According to the doctor, he saw a massive, strange rock, so he broke off a piece and left the rest behind—all 10,000 kilograms (22,000 lb) of it. When he got back to Washington, geologists took a look at what he’d found and said that it was the most rare type of meteorite—the pallasite.

Shortly after, the Civil War began, and Evans died. He had left behind some clues, saying that the rock was on a mountain near Port Orford, in a place that’s higher than the surrounding areas. Vague, yes, and doubly so in an area prone to rockslides. More questions were raised about the sample when later scientists matched it to a piece that came from a known meteorite in Chile. While it certainly called into question the authenticity of Evans’s claim, things became even more unclear in 1937, when a miner claimed to have found the meteorite. He had a piece that matched the one from Evans, but before more information came out, the miner disappeared.

Much later, in 1993, the case was reviewed, and the findings are now in the Smithsonian Archives. Evans wasn’t that well trained in geology, and he was also drowning in debt. The official conclusion was that he had somehow gotten a piece of the Chilean meteorite, which had been discovered around 1820. He had hoped to sell the location of his imaginary find for a hefty profit but died of pneumonia before he could.

6James Reed And The Founding Of San Jose

James Reed was an Irish immigrant who ultimately ended up at the head of one of the most notorious parties to attempt the Oregon Trail—the Donner Party. While everyone knows what happened to them, Reed’s story was equally fascinating and involved some anger and a lot of bizarre luck.

Reed, his wife, and their four children were part of the ill-fated Donner Party, but by the time they found themselves stranded in the mountains, Reed had already left. In October 1847, the Donner Party was in Nevada. The teamster in charge of one of the teams of oxen was hot, angry, and frustrated, so he took a whip handle to one of his oxen. Reed didn’t like the abuse of the animals and stepped in. When the teamster turned the whip on him, Reed stabbed the man in the chest and killed him. Reed narrowly escaped being the target of a hanging. Instead, he was exiled and left the group.

He rode ahead and completely missed the storms that would strand the rest of the party. Eventually, he managed to put together a rescue party and was one of the men that brought the survivors—including his entire family—to safety. With everyone safely on the other side of the mountain, Reed went on to move his family to what would become the thriving town of San Jose—with Reed’s help. He quickly rose to be one of the town’s leaders. There are still several city blocks of streets named after Reed and his family.

5The Fallacy Of Native American Aggression

One of the longest-lasting images of the Oregon Trail is that of aggression against the Eastern settlers perpetrated by the savage tribes of the West, who were angry about the encroachment on their land. We’ve all seen the images of wagon trains pulled into a defensive circle, warriors on horseback charging and firing arrows at the besieged travelers.

Only, that’s not precisely true.

There were tensions between the two groups, and there certainly was conflict—but the settlers actually killed more Native Americans than vice versa. Between 1840–1860, 362 pioneers were killed, along with 426 local Native Americans, mostly near the Humboldt and Snake Rivers and west of the Rocky Mountains. With each passing year, relations between the two got increasingly worse, for a couple of reasons. The ever-increasing (and seemingly never-ending) train of settlers often refused to pay tribute to the land they were crossing. They burned trees for firewood, killed some game, drove the rest away from their natural habitats, and brought disease.

For years, the relationship between the two groups was based more on trade than hostilities. A few times a year, Sioux and Cheyenne would head to Fort Laramie to trade buffalo skins and furs for things like blankets, tobacco, lead, and powder. In 1851, the Sioux signed a treaty called the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, agreeing to allow settlers from the east through their land for a yearly payment of $50,000. The treaty was short-lived, though, as officials not only refused to honor it, but more and more forts and military outposts were being built on Native American lands. There were several more attempts at signing a treaty, but in 1874, the gold discovered on reservation land became too great a temptation.

4John Shotwell And Trail Dangers

It’s estimated that there are an average of 10 graves for every 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) of the Oregon Trail. The popular image is that most people either died an incredibly violent death or, thanks to The Oregon Trail, dysentery.

However, cholera was one of the most common illnesses, spread by the huge number of travelers through contaminated drinking water. Once a person had contracted cholera, there was no set progression of the illness. Some died within hours, some were sick for weeks. Those that did die on the trail weren’t usually buried off to the side with a grave marker; graves were dug on the trails themselves, where other wagons and other families would pass directly over the body and pack the dirt down on top of it.

Accidents were another common cause of death, with many settlers having to adjust very quickly to the hardships of the road and the unpredictability of draft animals and livestock. Fatigue, hunger, and illness added to the difficulty. There are a large number of reports of people dying from being trampled by a runaway animal or falling and being crushed beneath a wagon. Firearm accidents were common: Many people who had never used guns before were forced to use them.

The first accidental death from a gun was the ironically named John Shotwell. On May 13, 1841, he had grabbed a shotgun, muzzle first, to pull it out of the back of a wagon. The gun discharged, shooting him in the heart. According to records, he lived for about an hour before finally dying.

3Sam Barlow’s Toll Road

When it comes to the supplies necessary to make the long trek from east to west, spare change for tolls probably isn’t one you’d think was at the top of the list.

The trail split at The Dalles, and people were forced to make a choice. They could either try to cross the Cascade Mountains, or they could take the the ferry down the Columbia River. There were only a handful of ferries, though, and waiting wasn’t an option—supplies at the intersection were low. Once the first group of settlers, including Sam Barlow, made it over the mountains, he saw a huge opportunity there. By 1846, he had gotten a charter to complete a road over the mountains, and he succeeded with the help of about 40 workers. The road opened that year, and Barlow charged $1 for every person (or head of cattle) and $5 for every team.

The road was a financial failure. Even though it became a regular route for travelers, by the time many got to this point, they couldn’t afford to pay the toll. Many of the men responsible for collecting the tolls were more sympathetic to the state of the travelers than they were dedicated to collecting their due, so they would often just let people pass without paying. By 1919, the road and the land became Oregon state property.

2The Triskett Gang

In 1852, the Triskett Gang went on record as being responsible for one of the worst mass killings of the era.

The earliest settlers got to set up camp—and home—in the choicest locations for gold mining. Those that came later occasionally found it easier to steal from the early birds, and that included Jack and Henry Triskett. The brothers, along with a handful of other gunmen, were responsible for a rash of robberies across California. Fleeing the law, they ended up in the Oregon town of Sailors’ Diggins. For the time, it was a massive town; the entire population of Oregon was about 10,000, and several thousand of them were in Sailors’ Diggins.

When the gang arrived, they rather unsurprisingly headed for the saloon and had a little too much to drink. When they got ready to leave, one of them killed a man in the street, setting off a chain reaction that ultimately left 17 people dead. Because most of the men were out mining, the dead consisted mostly of women, children, and the town’s elderly. Hearing the gunfire, the miners returned to town, and the brief standoff ended with the entire Triskett Gang dead. When the smoke cleared, though, it was found that sometime between their arrival and their end, the gang had cleared all the gold out of the assayer’s office. Totaling about 113 kilograms (250 lb), the gold is still missing to this day.

1The Mormon Handcart Tragedy

Not everyone who traveled the Oregon Trail did so with a wagon, oxen, and mules. Thousands of Mormons headed west not necessarily from the east coast but from Britain. By the time they started on the second leg of their journey, they couldn’t afford a typical wagon. Instead, Brigham Young invented a different sort of wagon, one that was pulled by the settlers themselves. At the height of the westward movement, there were about 10 companies set up to help travelers fund their journey. In August 1856, a group of 1,100 people left Nebraska. The trip, which took about four months to complete, ended up being one of the most fateful journeys of the Oregon Trail.

If it seems like August was a bad time to start the trip, it’s a bit of wisdom that the company leaders absolutely didn’t listen to—and it led to the deaths of more than 200 people. It was ultimately decided that, suffering and hardship notwithstanding, the trip needed to continue. Food was running low by the time they reached Wyoming. In order to lighten the loads, everyone was reduced from a baggage allowance of 7 kilograms (15 lb) to 4.5 kilograms (10 lb). That ultimately meant that many people opted to leave behind heavy winter clothing, which was just as much of a problem later as you’d think. By October, the weather—and the river crossings—meant that the pioneers were suddenly exposed to bitterly cold temperatures. Rescue missions were sent out, but with everyone suffering from the cold and the food shortages, the final death toll was somewhere around 25 percent.