Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Banknotes With Hidden Images And Symbols

Paper money has been around since China issued it in the seventh century. But not all banknotes are made of paper; they’ve been made of everything from wood and foil to leather and polymers. Here are the oddballs in the money world.

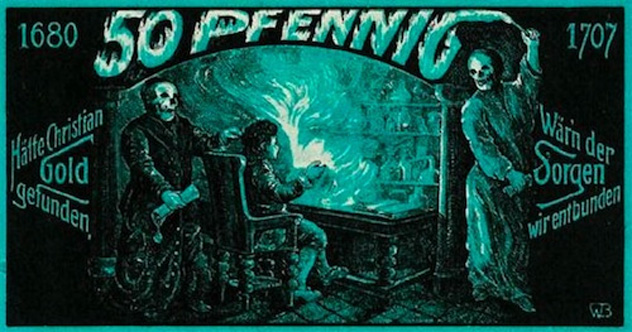

10Germany’s 50-Pfennig Emergency Money

Germany was already suffering shortages in coins and metals when World War I kicked off in 1914. With the advent of hostilities, silver prices skyrocketed, and copper and nickel were diverted to the war effort. Without coinage, commerce became nearly impossible, and municipalities and private businesses began printing paper money called notgeld or emergency money.

At first, these notgeld were plain, issued in 25, 50, and 75 pfenning (penny) notes, along with some in marks. Later, the notes featured colorful images of folklore, social satire, political statements, and even playing cards. These notes were so unique by the end of the war that collectors were gobbling up banknotes as quickly as they were issued.

For three postwar years, many notgeld were issued purely for collectors and were rarely circulated. During this time, serienscheine banknotes—a series of notes with the same thematic story depicted on them—were issued. But in 1921, Germany’s inflation evolved into hyperinflation, and the situation became so dire that currency itself became difficult to obtain. Postage stamps encased in aluminum or celluloid began to be used as currency.

In 1923, the Reichsbank issued a new currency, the Rentenmark, thus ending the era of notgeld.

9Burmese 1-Kyat Democracy Note

Until a few years ago, Burma had been fighting a civil war since it gained its independence in 1948, the longest civil conflict in the world. The resulting chaos played havoc with Burma’s monetary system, and the country’s odd banknotes will appear again on this list.

One of the key leaders in the country’s independence was General Aung San, who became the de facto prime minister. Just months before England relinquished control, Aung San was assassinated by a political rival. His daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, was just two years old.

Suu Kyi left Burma in 1960 and didn’t return until 1988 to care for her ailing mother. She found a country in transition from a dictatorship to a military junta. Using the lessons from Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Suu Kyi led a nonviolent campaign for democratic elections. The junta responded by arresting her, placing her under house arrest, and cutting her off from all communication. Simply putting her image on a poster or flyer was punishable by imprisonment.

The next year, the junta authorized a 1-kyat note with the national hero, General Aung San depicted on it. The watermark was simply to be the same image. Some unknown engraver, however, softened the general’s features to form a watermark with Suu Kyi’s illegal likeness. For the months it took for the junta to withdraw the banknote, democratic reformists needed only hold their currency to the light to see their leader.

Suu Kyi spent most of the next 20 years under house arrest and in 1991 won the Nobel Peace Prize. Finally, in 2010, she was released. Two years later, she and her party were elected to parliament.

8Oranienburg Concentration Camp’s 50-Pfennig Note

As soon as deportees arrived at Nazi-run concentration camps and ghettos during World War II, they had to exchange their cash and bonds for “local currency.” These local notes were poorly made, worthless, and rarely circulated because there was little to purchase in a camp or ghetto.

The first camp to issue such scrip was the Oranienburg Concentration Camp just outside Berlin. The camp opened in 1933 after a wealthy banker donated a lumber yard to the government. One of the first inmates was Horst-Willi Lippert, a graphic artist imprisoned for his anti-Nazi sentiments.

Lippert was ordered to design the printing plates for banknotes to be used within the camp. He used the notes to send a subtle message to the public that the camps were not voluntary communities where undesirables were relocated for everyone’s safety, as the Nazis claimed. His 5-pfennig note showed a guard tower standing over a barbed wire fence. His 1-mark note depicted an elderly man digging a trench. He drew a barbed wire and a pair of stern-looking armed guards on the 50-pfennig plates.

He didn’t stop there. After the first run of printing, Lippert scratched off the top of “g” in the word Konzentrationslager (“concentration camp”) on his printing plates, changing the word to Konzentrationslayer (“concentration killer”). The change can be seen in the image above.

The Nazis never caught on to Lippert’s subtle message or alteration, and Lippert’s notes became the template for money printed in other camps throughout the Reich. He survived the war and later verified his efforts.

7Canada’s $1,000 Devil’s Face Bill

In 1951, Queen Elizabeth II sat for famous Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh. One of the photos was used three years later for a new series of Canadian notes from $1 to $1,000. This new series would have the portrait of the queen on the right side of the banknote so that her image would not be marred when it was folded.

The selected photo, however, featured a tiara on Elizabeth’s head, and Canadians preferred informal depictions of the queen. Artists retouched the negative to remove it. When the artists did not retouch the hair behind the queen’s left ear, the change in brightness of her hair had an unexpected result. Just over a year after it began circulating, banks began receiving complaints that a demon hovered just behind the queen’s ear. Artists were commissioned to obscure the devil’s image, and the series was reissued in 1957. All the denominations were changed except the $1,000 bill. It waited several years before it was retouched.

The $1,000 bill is special for another reason. In 2000, Canada withdrew the denominations in its fight against organized crime. Gangsters and money launderers favored these large denominations (nicknamed “pinkies” due to their pink coloring) because they were easier and lighter to smuggle. For instance, a $1 million payment in $100 bills would weigh 10 kilograms (20 lb), while the same payment in $1,000 bills would weigh just 1 kilogram (2 lb). Often, these criminals would use the notes to pay debts only to each other, keeping the bills out of circulation. As of 2011, nearly a million $1,000 bills were as yet unreturned to the Canadian mint, mostly hoarded by the criminal elite.

6Congo’s 20,000-Zaire notes

Change in leadership has often played havoc with a nation’s currency. When the Shah was overthrown in 1979, subsequent issues of Iranian money had the symbol of the Islamic Republic stamped over his face. When Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gadhafi were deposed, their country’s citizens had to live with their images on their money for a time.

Within months of gaining its independence from Belgium, the mineral-rich Democratic Republic of the Congo was immersed in a civil war, and its democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, was deposed and murdered. Worse, the CIA installed as dictator the man most responsible for Lumumba’s assassination, the pro-Western Joseph Mobutu.

For 31 years, Mobutu crushed dissent and plundered the country he renamed Zaire, acquiring one of the largest personal fortunes in the world. Meanwhile, corruption and mismanagement resulted in the decay of Zaire’s infrastructure, resulting in chronic poverty. When Mobutu was himself deposed in 1997, he escaped to one of his homes in Morocco, where he died a few months later from prostate cancer.

The country readopted the name “The Democratic Republic of the Congo” but faced severe shortages of banknotes. So they recycled old Zaire 20,000 notes with Mobutu’s face punched out. These temporary notes were used until new currency could be printed and issued.

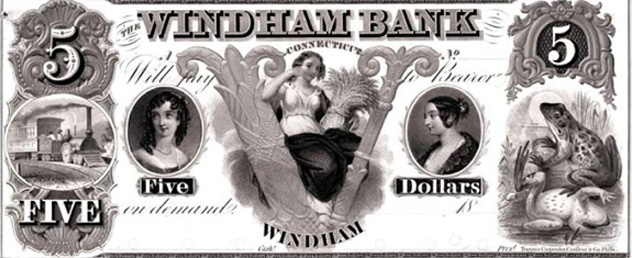

5Colonial America’s Privately Issued $5 Bill

During the British colonial period before the Revolutionary War, American banks issued their own currency to local communities. The earliest notes were simple in design and were easily counterfeited. More elaborate designs were then adopted. As an added anti-counterfeiting feature, these included images based on deeply local folklore, which only members of that community would understand.

One such story originates from the small eastern Connecticut town of Windham. The colonies were in the midst of the French and Indian War in the mid-1750s, and one hot June night, the town’s residents were awoken by a racket. Believing they were about to be attacked by a tribe of Native Americans or French soldiers, the villagers grabbed their weapons and headed toward the noise. Their courage failed them as they approached a pond, and they hunkered down and waited for dawn. When the Sun rose, they found that the noise came not from the enemy but from hundreds of frogs, half of them dead, who apparently fought over the drought-stricken pond.

Shortly afterward, the Windham Bank issued a $5 bill with a pair of frogs fighting each other as a community symbol. The two women featured on the note are probably local women, their names lost to history.

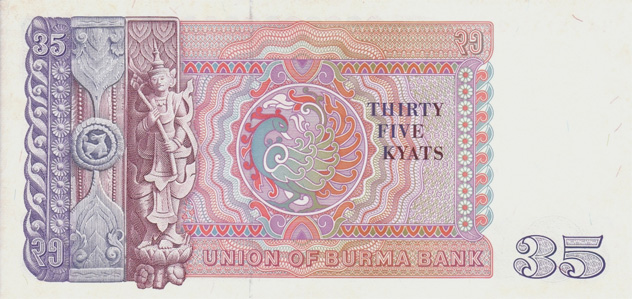

4Burma’s 35 Kyats

Nearly every country issues currency in denominations based on multiples of five and 10. In other words, they have currency in 1’s, 5’s, 10’s, 20’s, 50’s, 100’s, 500’s, and 1,000’s. But not Burma.

General U Ne Win was born Shu Maung in 1911. At the age of 30, he joined the Burma Independence Army—sponsored by the Japanese—to rid Burma of British rule. He changed his name to Ne Win, which means “brilliant as the Sun.” When it became clear the Japanese meant to replace themselves as Burma’s rulers, U Ne Win switched sides and helped drive them from his homeland.

When Burma gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1948, U Ne Win became the country’s supreme commander. He took control of the country from Prime Minister U Nu in 1958 and again in 1962. The second time, he also became ruler for life.

As dictator, U Ne Win was incompetent and drove his country into poverty. He was also eccentric. He was known to walk backward over bridges to ward off evil spirits and was said to bathe in dolphins’ blood to reach the age of 90 (a multiple of his lucky number, nine). In 1970, U Ne Win changed the country’s traffic regulations, so that cars drove on the right-hand side of the road instead of the left. The reason? His astrologist warned him that Burma was becoming, too left-wing in its politics.

U Ne Win was also fascinated with numerology—fortune-telling with numbers. In 1985, he printed 15-, 35-, and 75-Kyat notes. In 1987, he issued notes based on multiples of his lucky number. What followed were currencies in 45- and 90-Kyat denominations. Fortunately for the Burmese citizens, Ne Win was eventually deposed, and his weird denominations were demonetized. He died under house arrest at the age of 91. Maybe there’s something to bathing in dolphin’s blood?

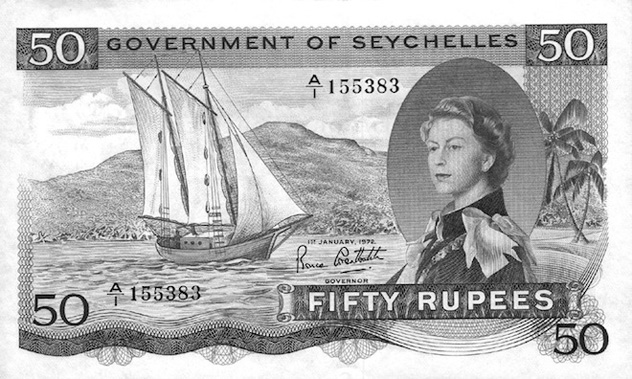

3Seychelles 50-Rupee Note

It should not be a surprise that Queen Elizabeth II appears again on this list, as her likeness can be found on the denominations of 33 different countries, more than any other person in history. To date, 26 different portraits of her have been the model for these images.

In 1968, the British commonwealth of Seychelles issued 50-rupee banknotes with a depiction based on a 1955 portrait of the queen commissioned by the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers. The palm trees to the right of the queen spell out the word “sex,” though you might have some trouble spotting it.

At first, this was thought to be a printing mistake. The two artists commissioned to draw the palm trees were not the culprits: Their drawings and designs were examined and did not have the palm trees in that configuration. The engravers therefore probably altered the design, but because of fears of counterfeiting, their identities were kept secret. Another banknote—the 10-rupee note—issued in the same 1968 series also has a hidden word. Under the flipper of a sea turtle is the word “Scum.”

While there is little supporting evidence, some have speculated that someone who supported Seychelles independence from Britain inserted the secret words to embarrass the crown. Neither the 10-rupee nor 50-rupee banknotes were withdrawn from circulation until 1973. Seychelles won independence in 1976.

2The Quasi-Universal Intergalactic Denomination

Not to be mistaken for the British quid (a slang for the pound sterling), the Quasi Universal Intergalactic Denomination (QUID) was developed to be used by future space travelers. Looking like miniature Nerf balls encased in plastic, QUIDs were developed by England’s National Space Center and the University of Leicester for the foreign exchange company Travelex. The Nerf balls represent the Sun, with the eight planetary inhabitants of our solar system circling along the QUID’s rim.

“None of the existing payment systems we use on Earth—like cash, credit, or debit cards—could be used in space for a variety of different reasons,” said Professor George Fraser of Leicester. “Anything with sharp edges, like coins, would be a risk to astronauts, while the chips and magnetic strips used in our cards on Earth would be damaged beyond repair by cosmic radiation.”

He added: “What’s more, because of the distances involved—it is more than 230,000 miles [375,000 kilometers] from the Earth to the Moon—chip and PIN technology is also out of the question.”

The QUIDs are made of teflon, a polymer resistant to the extremes of space, and have rounded edges. Each of the planets on the QUID has a code, like serial numbers on paper money. Back in 2007, one QUID was worth $12.50, €8.68, or £6.25.

The QUID has competition. In 2013, PayPal announced that it’s trying to develop an interplanetary monetary system that works without credit cards, currency, or QUIDs.

1Germany’s 10,000-Mark Reichsbanknote

After Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles to end World War I in 1919, war reparations destroyed its economy. First, Germany had to relinquish valuable coal-rich territory such as the Saar (put under the control of the League of Nations) and Upper Silesia (given to Poland). Without these territories, a German financial recovery was near-impossible.

Second, Germany was required to take sole responsibility for the war. It would therefore funnel billions of marks to the rest of Europe, specifically France and Belgium. Already crippled economically by the war, Germany simply printed money to meet its payments, sending its economy into hyperinflation. A single mark would buy virtually nothing, and larger and larger denominations had to be printed.

By 1922, the Reichsbank was forced to issue 10,000-mark notes. It was decided that a painting by the famous German master Albrecht Durers called Portrait of a Young Man would appear on the front. An unknown engraver, however, added a political statement, subtly drawing the image of a hooded vampire—signifying France—standing behind the young man’s left shoulder, about to suck his blood. It’s not easy to see, but tilt your head to the right. Even after the vampire was discovered, the Reichsbank refused to pull the notes from circulation and even reissued more with the vampire still in place.

The German economy did not improve. When the 10,000-mark note was issued in January 1922, it purchased 110 kilograms (250 lb) of meat. By the end of the year, it purchased only 2 kilograms (5 lb). By 1923, 100,000 marks was equivalent to one US dollar. A year later, the same dollar was equivalent to 4.62 million marks.

Steve is the author of 366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency: The Private, Political, and Military Decisions of America’s Greatest President and has written for KnowledgeNuts.