Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

Travel

Travel 10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

Travel

Travel 10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

10 Lesser-Known Transport Disasters Of The 20th Century

The sinking of the Titanic, the collision of the SS Mont-Blanc, and the Hindenburg explosion are all well-known transport disasters that are always remembered and talked about. They’ve become icons, have been made into movies, and have ensured their place in history, never to be forgotten. But there are many more disasters out there that each one mattered just as much for the people involved. Each one made our world a safer place.

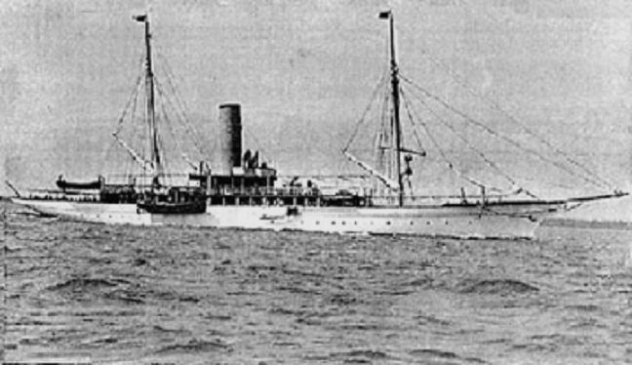

10 The Iolaire

On January 1, 1919, two months after the end of World War I, British sailors who’d survived the perils of both the ocean and the war were returning to their families on the Isle of Lewis and Harris, only to tragically perish within miles of reaching home.

The Iolaire (which means “eagle” in Gaelic) was built as a luxury yacht in 1881. During the war, it was equipped with guns and performed anti-submarine and patrol work. The Isle of Lewis and Harris saw a fifth of its population of 30,000 killed in World War I; the crew of the Iolaire were the lucky ones, eager to celebrate the New Year with their families.

Before anyone could celebrate, the ship struck the rocks known as the Beasts of Holm. It was only meant to carry 100 people, but there were almost 300 aboard, with only 80 life jackets and two lifeboats. It was expected to dock in Stornoway Harbour, but due to low visibility, it struck the rocks at the entrance of the harbor and quickly sank, less than 1 kilometer (0.6 mi) from shore. While 205 perished, 40 were saved by a brave man who improvised a rescuing implement from a rope, and 39 more were able to make it to shore on their own.

A naval inquiry was held in private on January 8, its results not being released to the public until 1970. It reached the conclusion that due to the fact that no officers survived, “No opinion can be given as to whether blame is attributable to anyone in the matter.” Numerous other inquiries, both official and unofficial, were held, none of which settled the matter. The weather wasn’t very bad, but those in charge should have taken safety precautions, like slowing down while approaching the harbor and having more lifeboats.

The site of the wreck is marked today by a pillar that reminds everyone who enters Stornoway Harbour of the cruel irony that befell those who survived the war and were so close to enjoying peace.

9 USS Akron

Following the example of the Hindenburg, the US built two helium-filled airships, each 239 meters (784 ft) long and carrying enough fuel to travel 16,900 kilometers (10,500 mi). One of them was named the USS Akron and was commissioned by the US Navy in 1931. Its mission was to provide long-distance scouting in support of fleet operations, and after a number of trials, the airship was equipped with reconnaissance aircraft and a system designed for in-flight launch and recovery of Sparrowhawk biplanes.

On a routine mission, disaster struck. During the early hours of April 4, 1933, off the coast of New Jersey, a storm began, which caused the airship to strike the water with its tail. The Akron quickly broke apart. What’s intriguing is that it carried no life jackets and only one rubber raft, which dramatically diminished the crew’s chances of survival. Of the 76 onboard, 73 drowned or died of hypothermia.

Although the weather was certainly a factor, Captain Frank McCord is also considered responsible, for flying too low and not taking into account the length of his ship when he tried to climb higher. It is also believed that the barometric altimeter failed due to low pressure caused by the storm.

Akron’s sister ship, the USS Macon, was also lost off the California coast in 1935. Fortunately, that time, only two people perished. These events prompted the US to end its rigid airship program.

8 Junyo Maru Tragedy

The Japanese are remembered for being extremely cruel to their captives during World War II, especially to prisoners of war, who were moved around the Pacific in rusted ships and used for forced labor. The problem with these ships was that they were not marked with a red cross in order to be identified as prison ships per the Geneva Convention, which made them vulnerable to being sunk by Allied aircraft or submarines. The largest maritime disaster in World War II occurred because of this.

On September 18, 1944, the Junyo Maru was torpedoed in the Indian Ocean by the British submarine HMS Tradewind, which couldn’t have known what cargo the ship was carrying. Of the 6,500 Dutch, British, American, Australian, and Japanese slave laborers and POWs onboard, 5,620 died as a result. The Junyo Maru was sailing up the west coast of Java from Batavia (now called Jakarta) to Padang, where its prisoners were to be taken to work on the Sumatra Railway.

Conditions onboard were indescribably bad. Many people were literally packed into bamboo cages like sardines. Those in charge put their life jackets on as soon as they left, whereas the POWs could only count on two lifeboats and a few rafts.

Even more tragically, the approximately 700 POWs who were pulled from the water were still taken to work in the Sumatra Railway construction camps. Only about 100 survived.

7 MV Wilhelm Gustloff Disaster

Nazi Germany designed a state-controlled leisure organization in order to show its citizens the benefits of living in a national socialist regime. Working-class Germans were taken on tours for holidays aboard the MV Wilhelm Gustloff and the program, nicknamed Strength Through Joy, became the largest tour operator in the world in the 1930s.

This all ended when World War II began. In 1945, the Wilhelm Gustloff became part of Operation Hannibal, the German evacuation of over one million civilians and military personnel due to the advancing Red Army in Prussia. Over 10,000 people, 4,000 of whom were children, were crammed onto the ship, all of them desperate to reach safety in the West. The ship was only meant to carry 1,800 people.

The Wilhelm Gustloff set off on January 30, 1945, against the advice of military commander Wilhelm Zahn, who said it was best to sail close to shore and with no lights. Instead, Captain Friedrich Petersen decided to go for deep water. He later learned of a German minesweeper convoy which was heading their way and decided to turn on the navigation lights in order to avoid a collision in the dark. This would soon prove to be a fatal decision. The Gustloff was carrying anti-aircraft guns and military personnel but wasn’t marked as a hospital ship, which would have protected her. Soviet submarine S-13 needed no second invitation to torpedo the shiny target three times.

Ample rescue efforts were made, which saved approximately 1,230 people. Over 9,000 perished in the cold waters of the Baltic Sea, the largest loss of life in a single ship sinking.

6 Gillingham Bus Disaster

On the evening of December 4, 1951, 52 Royal Marine cadets, boys between 10 and 13 years old, were marching from a barrack in Gillingham, Kent, to one in Chatham to watch a box tournament. Their military uniforms were dark clothes and had nothing on them to make the cadets visible. The entrance to the Chatham Royal Naval Dockyard had a malfunctioning light, which made it impossible for the driver of an approaching double-decker bus to see the boys. He plunged right through them before stopping.

The driver, John Samson, had 40 years of experience behind the wheel, but inexplicably for the foggy weather, he didn’t have his headlights on. He claimed to have been traveling at no more than 32 kilometers per hour (20 mph). According to the only adult who was with the boys, Lieutenant Clarence Carter, Samson was going at least twice as fast.

Regardless of the bus’s speed, 17 boys died on the spot, with seven more sent to the hospital. Never before had there been such a tragic loss of life on British streets, and the victims were given a grand military funeral at Rochester Cathedral. Thousands of locals attended. The incident was ruled an accident despite the driver not turning on the headlights or braking until he was a few meters away. Samson was later fined £20 and had his right to drive revoked for three years.

Every such disaster is followed by improvements in order to prevent further loss of life. This time, it was decided that British military marchers will wear rear-facing red lights at night.

5 Harrow & Wealdstone Rail Crash

October 8, 1952, is remembered by Londoners as the day of the worst peacetime rail crash in the UK. It was only exceeded by the Gretna Green disaster during World War I in 1915, when 227 Scottish soldiers headed for the front perished. The Harrow & Wealdstone rail crash involved three trains—a local passenger train from Tring, a Perth night express, which was running late because of foggy conditions, and an express train from Euston.

The driver of the Perth train passed a distant yellow signal, which means “caution,” without slowing, possibly because he couldn’t see it due to the weather. He also passed a later semaphore, which indicated “stop.” He only hit the brakes when it was already too late. Meanwhile, the train from Tring was waiting at the Harrow & Wealdstone Station for its passengers to embark. The Perth train impacted at approximately 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph). The disaster wouldn’t stop there. The fast-moving express from Euston approaching on a different line hit the debris from the initial impact and derailed.

In total, 16 carriages were destroyed, 13 of which were compressed into a pile only 41 meters (134 ft) long, 16 meters (52 ft) wide, and 9 meters (30 ft) tall. The human casualties would total 112 (102 immediately after the accident and 10 more later at the hospital), and 340 were injured.

Although the exact causes and persons responsible were hard to determine, it is believed that a combination of fog, misread signals, and out-of-date equipment caused the horrific crash. All the equipment was working, and the drivers were experienced men; all they needed was an updated system to back them up. The accident sped up the process of introducing the Automated Warning System of the British Railways. The system works by giving a driver who passes a caution or danger signal automated feedback, whether he saw the signal or not, and automatically applying the brakes.

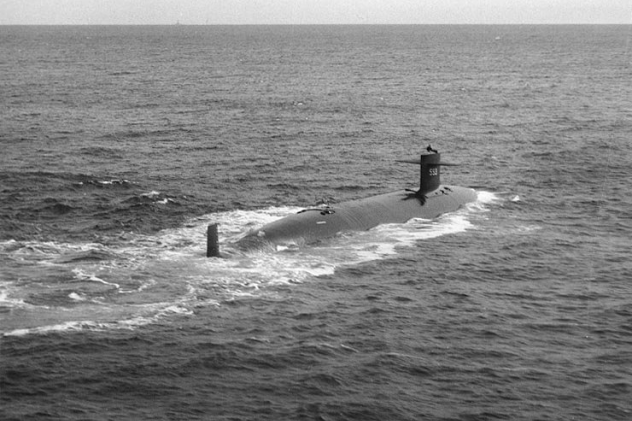

4 USS Thresher Sinking

The USS Thresher was the first in a new fleet of nuclear-powered attack submarine. It was commissioned in 1961 and went through numerous sea trials to test its new technological systems. As if foreshadowing the disaster that was to strike later on, these trials were interrupted by the failure of the generator while the reactor was shut down, which caused the temperature in the hull to spike, prompting an evacuation. Another setback occurred when the Thresher was hit by a tug and needed extensive repairs.

On April 10, 1963, the sub was conducting drills in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Cape Cod, when it suddenly plunged to the seafloor and broke apart. All 129 passengers were killed—96 sailors, 16 officers, and 17 civilians. During the investigation into the accident, a leak in one of the joints in the engine room was discovered, which caused a short circuit in the electrical system and made it impossible to resurface the Thresher. The sub had no other choice but to sink and implode due to increasing water pressure.

The disaster mobilized the US Navy to put more effort into SUBSAFE, a program designed to rigorously control the quality of nuclear submarine construction.

3 MV Derbyshire Sinking

The MV Derbyshire is the largest British bulk carrier lost at sea. Built in 1976, it was a majestic ship built in 1976 at 281 meters (922 ft) in length, 44 meters (144 ft) in width, and 24 meters (79 ft) in depth. It had been in service for only four years when it set sail toward its doom on July 11, 1980, carrying 150,000 tons of ore.

On September 9 or 10, Typhoon Orchid struck the Derbyshire in the East China Sea, just as the ship was approaching its destination. At the time, it was carrying 44 people, all of whom perished during the journey from Canada to Japan, where the ship was meant to transport its cargo.

What sets this disaster apart from others is that the ship seemed to be lost forever, with initial searches for the wreckage turning up nothing. The absence of any mayday call or distress signal beforehand was also intriguing to the families of those lost. A formal investigation was conducted seven years later in 1987. It concluded that no structural or other failures were to blame; the weather conditions were responsible.

The grieving families were not convinced, and they decided to from the Derbyshire Families Association (DFA) to work together toward the truth. They managed to raise enough funds to finally find what remained of the Derbyshire in 1994, lying on the seabed more than 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) down in the abyss. DFA members continued to push for a number of investigations, which resulted in increased ship safety over the years. While the 1970s were plagued by bulk carrier sinkings, with 17 lost each year. The numbers are much lower today.

2 Bihar Train Accident

Were it not for the British rule over India, which aimed to improve the transport system among other things, the Bihar train accident would have never happened. On June 6, 1981, a train with around 1,000 passengers crowed into nine coaches was traveling through the Indian state of Bihar, 400 kilometers (250 mi) away from Calcutta. It was the monsoon season in India, which meant that heavy rains made the tracks slippery, and the river below was swollen.

It is believed the tragedy that followed was caused by the driver, who saw a cow along the tracks and braked hard. Cows are sacred animals in the Hindu religion, and he was a devout follower. Due to the rain, the tracks were too slippery, and the wheels failed to grip, causing the carriages to plunge into the Baghmati River below, sinking fast. Rescue efforts were hours away, and by the time they arrived, almost 600 people had died, and another 300 remain missing.

1 Ufa Train Explosion

The 1980s were difficult times for Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who was trying to hold together the Soviet Union and maintain the Communist Party’s commanding role. At the same time, a series of disasters couldn’t hide the fact that the country’s infrastructure was old and dangerous. One of these disasters happened on June 4, 1989.

Two Russian passenger trains with hundreds of people onboard were passing one another near the city of Ufa, close to the Ural Mountains, when they met an extremely flammable cloud of gas leaking from a nearby pipeline. Sparks released by their passing blew both trains to pieces. Seven carriages were reduced to dust, while 37 more were destroyed, along with the engines. More than 500 people perished, many of whom were children returning from a holiday on the Black Sea. The force of the explosion was estimated to be similar to 10 kilotons of TNT, which nearly equaled that of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The fireball formed was 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) long and destroyed all trees in a 4-kilometer (2.4 mi) radius.

The pipeline going along the rail lines was full of propane, butane, and hydrocarbons, and the pressure within was high enough to keep it in a liquid state. On the morning of June 4, a drop in pressure was observed, but instead of checking it out, the people in charge increased the pressure. Consequently, clouds of heavier-than-air propane formed and left the pipe, traveling along the rails. All they needed was a spark.

As with many disasters, the Ufa train explosion happened because finishing something quickly at minimal cost was more important than long-term consequences. The pipeline had more than 50 leaks in three years, and the Soviet Ministry of Petroleum didn’t want to admit their negligence. Worse, railway traffic controllers didn’t have the authority to halt trains on the Trans-Siberian railway, even if they smelled gas.

Teo loves animals, chocolate, and constantly finding out more about this magnificent and diverse world.