Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 People Who Were Patient Zero of a Deadly Epidemic

Keep calm, carry on, and maybe wash your hands a little more often. That’s the gist of the advice given to the general public in the event of a deadly epidemic: less panic, less pandemic. But behind the scenes, epidemiologists are in a frantic race against time to track the spread of disease back to its origins and, hopefully, find some answers on how to stop it.

Like an earthquake, every deadly epidemic has an epicenter, a central point where the disaster is set in motion. In the case of an epidemic, a central point is a person, and that person is known as patient zero. Here are 10 of the most famous patient zeros in history.

10 Typhoid Mary

We begin with the most famous patient zero of them all, “Typhoid Mary,” whose real name was Mary Mallon. Mary was just 15 when she emigrated from Ireland to the US in 1884 and found work as a maid.

By 1906, Mary had risen to the position of cook for the wealthy Warren family, who spent their summers at Oyster Bay, Long Island. None of Mary’s employers had had any problems with her culinary offerings, but it was a bit of a coincidence that the people Mary cooked for had a habit of becoming seriously ill.

Of the eight families Mary had worked for before the Warrens, seven of them had experienced cases of typhoid. Mary was found to be a carrier of typhoid fever, but as she was not sick herself, she refused to be quarantined. In 1907, New York was at the center of a typhoid epidemic that affected around 3,000 people, and Mary was thought to be its patient zero.

After two years of forced confinement on North Brother Island, Mary was finally released and took a job (under a false name) as a cook in a maternity hospital. Another typhoid outbreak ensued, at which point Mary was permanently incarcerated on Pest Island in the East River.[1] She died in isolation on November 11, 1938. Her obituary officially named her as the cause of 51 cases of typhoid and three deaths.

9 Frances Lewis

Cholera was a serious threat to public health in Victorian London. In 1854, over the course of just 10 days, 500 people dropped dead within a few blocks of central London. Symptoms of cholera included vomiting, diarrhea, stomach cramps, and extreme thirst, and a patient who began feeling queasy could be dead that day.

By the end of the cholera epidemic, over 10,000 people were underground, and scientists were desperate to determine where this lethal epidemic originated. Ground zero, they found, was in the diaper of a tiny, five-month-old baby named Frances Lewis.

Local physician John Snow plotted on a map the exact locations where cholera victims had died. Known later as the ghost map, Snow’s map showed that most victims lived close to a water pump on Broad Street. It seems that Frances Lewis’s mother was washing her baby’s soiled diapers in pails of water that she then emptied into the cesspool in front of her house on Broad Street.[2]

Victorian London was not known for its cleanliness, and the cesspool leaked directly into the local water source, poisoning thousands of the area’s residents. Soon after the pump was condemned, the cholera epidemic came to an end.

8 Mabalo Lokela

Ebola is considered one of the most alarming diseases of the 21st century. Ebola kills by causing its victims to suffer massive internal bleeding. It is a disease for which, even now, we have no cure, no vaccine, and no real idea why it keeps coming back.

The world’s first recorded victim of Ebola was a teacher named Mabalo Lokela. Mabalo lived in the town of Yambuku in the Democratic Republic of Congo and returned from a trip north in August 1976 with a high fever. Initially, medics diagnosed Mabalo with malaria. But after two weeks of dreadful symptoms—uncontrollable vomiting; trouble breathing; and bleeding eyes, nose, and mouth—he died.

Unfortunately, the Ebola virus did not die with him, and many of the people who came into contact with Mabalo during his sickness contracted the disease. As a result, around 90 percent of the people in Mabalo’s village died, and the world reeled as brave epidemiologists tried to work out how to stop this killer virus from spreading.[3]

The most devastating outbreak of Ebola the world has ever seen happened in 2014 and claimed the lives of over 5,000 people in one year. As of the end of the outbreak in June 2016, more than 11,000 people had died from the disease, five times more than all other Ebola outbreaks combined. The West Africa Ebola outbreak of 2014 was traced to a two-year-old boy living in a remote village deep in the Guinean forest region.[4] Emile Ouamouno’s death was quickly followed by his three-year-old sister, Philomene, their pregnant mother, their grandmother, and many other people from his village. But it would be months before Ebola got the worldwide attention it badly needed.

7 Dr. Liu Jianlin

Over the course of nine months, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) crept steadily around the globe, taking a total of 774 lives across 37 countries and leaving many gravely ill. First diagnosed in the Guangdong province of China in November 2002, SARS was initially described as “atypical pneumonia.” Flu-like at first, the vicious virus quickly developed into full-on pneumonia and eventually respiratory failure.

As is often the case, we had no idea what we were dealing with until it was too late. By the time the world started to notice this contagious disease, a certain Dr. Liu Jianlin, a medical doctor from Guangdong province, had checked into Hong Kong’s Metropole Hotel.

Described later as hyper infectious, Dr. Liu is believed to have infected around 12 people at the Metropole before dying of respiratory failure. One of those 12 people was a lady named Sui-Chu Kwan, a resident of Scarborough, Ontario, who—feeling right as rain—boarded a plane for Canada two days after bumping into Dr. Liu.[5]

6 Edgar Enrique Hernandez

“Kid Zero” may sound like the name of a superhero sidekick, but it was actually the nickname of the first human infected with swine flu. Four-year-old Edgar Enrique Hernandez from Mexico tested positive for H1N1 swine flu in March 2009. Soon, photos of his smiling face were on the front page of every newspaper.

In Edgar’s hometown, the rural town of La Gloria, several hundred people fell ill in a matter of weeks, and two children died. According to the World Health Organization, H1N1 has caused or contributed to the deaths of over 18,000 people as of January 2016. However, the CDC reports that the death count worldwide may actually be between 150,000 and 575,000.

Many residents of La Gloria blame nearby industrial hog farms for the outbreak, but the jury is still out on whether H1N1 originated in the pigpens. Also unconfirmed is whether little Edgar was actually the first human to contract the H1N1 swine flu.[6] Regardless, the local authorities of La Gloria recently erected a bronze statue of Edgar in an interesting attempt to bring tourists to the town famous for swine flu.

5 Patient Zero MERS

The MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic in South Korea was officially declared over in July 2015. Also known as “camel flu,” this deadly respiratory disease was first detected in Saudi Arabia and is thought to be derived from bats. No one knows the identity of the first victim of MERS in Saudi Arabia. But when the virus hit South Korea, causing a serious epidemic that killed 36 people, it was easy to trace the source to one man.

Patient zero in the South Korean MERS outbreak first sought medical attention for a nasty cough and high fever on May 11, 2015. At a clinic in his hometown of Asan, south of Seoul, doctors examined the patient over the course of four days but were at a loss as to the cause of his ill health.

On May 20th, the patient sought help at the Samsung Medical Center in Seoul and revealed that he had recently returned from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Finally, he was correctly diagnosed with the highly contagious virus. By then, patient zero had infected the two men who shared his hospital room, his doctor, some people sharing his hospital ward, and their visiting relatives.[7]

There were 186 confirmed cases of MERS in South Korea. Thousands of people were quarantined to stop the spread of the virus, a precaution that brought chaos to the city of Seoul.

4 Gaetan Dugas

The most infamous patient zero on our list is a man named Gaetan Dugas. He was an Air Canada flight attendant and was identified by scientists in the late 1970s as the first person to bring the HIV/AIDS epidemic to the US.

Journalist Randy Shilts publicly named Dugas in his 1987 book And The Band Played On. Upon the book’s release, the New York Post covered the story with the headline, “The Man Who Gave Us AIDS,” forever linking the name Gaetan Dugas with the devastation of the HIV/AIDs epidemic.[8]

However, scientists have now learned that it is doubtful that patient zero in the HIV/AIDS epidemic was Gaetan Dugas. A recent genetic study using blood samples taken in the late 1970s has concluded that the virus probably came to New York City in 1970 and was linked to existing viruses then present in Haiti and other Caribbean countries.

AIDS is not the cause of death of those infected, but it plays a contributing factor. Most people die from another condition that becomes worse with their weakened immune systems. As of February 2020, about 30 million people worldwide have died from AIDS-related illnesses.

3 Patient Zero SARS-Cov-2

By December 2019, the first cases of SARS-Cov-2, or COVID-19, had appeared in China. The coronavirus, which caused the global pandemic, likely originated at a Chinese wet market. However, there is still so much to be discovered about the virus and its origins.

According to the Chinese government, patient zero may have been identified as a 55-year-old Chinese man from Hubei province. In late 2019, rumors about a strange new flu were beginning to circulate in Wuhan. On China’s social media platform WeChat, users had been discussing their coughs and colds for weeks with words like “SARS” and “shortness of breath” spiking from mid-November.

By early December, a so-called “pneumonia of unknown origin” had been identified, and patients—many of them workers or customers of a well-known market—were finding their way to the hospitals in Wuhan for treatment.[9] While most people have no or few symptoms, some get very ill and can even die. What begins as a cough can lead to shortness of breath. In more severe cases, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may occur after about 10 days after initial symptoms begin. At this point, hospitalization for breathing treatments and intubation may be required.

The physical and mental effects of the virus are still being studied, and it may be years before we truly understand the virus. As of May 2021, there have been more than 150 million confirmed cases and more than three million deaths worldwide due to COVID-19.

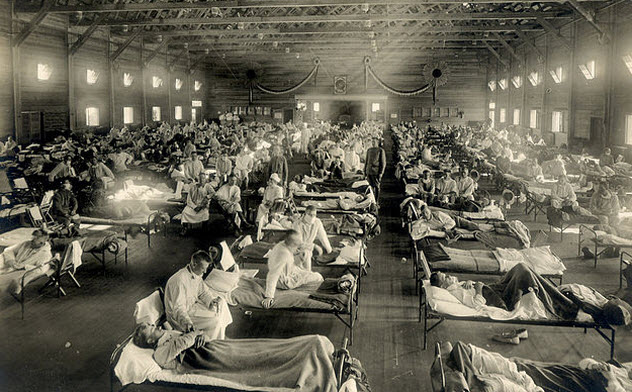

2 Private Albert Gitchell

Several nasty viruses spring to mind when pondering deadly pandemics—the bubonic plague, cholera, Ebola, and typhoid. But what about the benign-sounding Spanish flu? The Spanish flu is one of the most devastating pandemics the world has ever seen and is thought to have killed between 20 and 40 million people.

Yes, you read that right. Million. In the year 1918, with much of the world overwhelmed by World War I, the Spanish flu spread silently from person to person, eventually infecting up to one-third of the world’s population.

It all began on Monday, March 11, 1918, with a cough. A nasty cough coming from Private Albert Gitchell, a cook at the U.S. Army Base in Fort Riley, Kansas. Military medics knew how quickly a virus could spread in camp conditions and had Gitchell immediately quarantined. But it was too little too late.

Gitchell had cooked dinner for hundreds of soldiers stationed at the camp the night before, and by midday, over 100 soldiers were sick. Almost half of the soldiers died from their symptoms, and the flu spread like wildfire throughout the U.S. and Europe, across enemy lines, and into the rest of the world.[10]

1 Goodwoman Phillips

Goodwoman Phillips was not the first person to die of the bubonic plague, and she certainly wasn’t the last. In fact, the bubonic plague8 Fascinating Facts About Plague Doctors is still present today. Annually, there are hundreds of cases and deaths, but it does not become the pandemic of previous centuries—like the Black Death in the 14th century—as it can be treated with modern antibiotics. Between 2000 and 2010, there were 21,725 people affected, with 1,612 deaths worldwide.

Goodwoman Phillips earned her inclusion on our list of patient zeros as she was the first person to officially die of “plague” during the Great Plague of London in 1665–66. Thanks to the work of John Graunt, a London draper with an eye for statistics, deaths from the bubonic plague were meticulously recorded. All told, more than 68,000 deaths from the plague were recorded in a city of around 450,000 people, over 15 percent of the population.[11]

According to the people of London, the plague that befell the city was the result of two specific occurrences: the appearance of a comet in the skies over London and the coronation of King Charles II. The comet was seen as a bad omen that would bring about the end of days, while the plague was rumored to follow a coronation as a sign that the new king did not have God’s favor.

We know now that the Great Plague of London was actually the result of squalid living conditions that put people near plague-infected rats that were covered in plague-infected fleas.

Toni Marie Ford is a freelance writer, cinema lover, and slow travel enthusiast from the UK who has been enjoying a nomadic lifestyle since early 2014. Visit her blog, www.worldandshe.com, or follow her on Twitter or Instagram.