Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Early Forensic Techniques That Solved Murders

Even though their portrayals are often inaccurate, TV shows like CSI and Bones have popularized forensics among the general public. Some techniques have proven their worth after hundreds, even thousands, of cases. Newer forensic methods struggle for recognition while older ones are falling out of favor. Regardless, these cases probably wouldn’t have been solved without them.

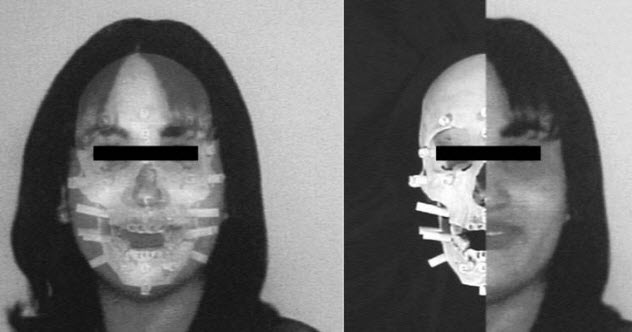

10 Superimposition

Rachel Dobkin

In April 1941, Harry Dobkin murdered his wife, Rachel, and left her body in the cellar of a London chapel destroyed by the Blitz. He was hoping that she would be classified as another bombing casualty.

Authorities found her over a year later. Unfortunately for Harry, the body was assigned to pioneering pathologist Keith Simpson. He spotted a broken bone in Rachel’s throat, suggesting that she had died of strangulation. He was also able to pinpoint the time of death to 12–15 months prior to her discovery.

Police went through missing persons records and found Rachel Dobkin. She had disappeared around the right time, she was the right age, and her husband worked near the chapel. Using a new technique called superimposition (pictured above with another person), Simpson compared a photograph of the skull with an antemortem photo of Rachel and got a match. Harry Dobkin was convicted and hanged.

9 Ballistics

St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

In 1929, Al Capone’s men dressed up like cops and gunned down his competition in the notorious St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. But few people know that it helped popularize ballistics.

Calvin Goddard, the “father of ballistics,” had already showed that you can match a bullet to a gun by studying the marks left on the bullet. In 1925, with the help of Phillip Gravelle, Goddard invented the comparison microscope to examine two objects simultaneously, making it much easier to compare bullet striations.

A few months after the shooting, hit man Fred Burke was arrested for killing a cop. Police recovered two Thompson submachine guns from his home. Goddard was brought in and proved conclusively that they had been used in the massacre. Nobody else was charged in the killings, but Goddard’s new technique—dubbed “ballistics-forensics”—became an integral part of solving crimes.

8 Forensic Dentistry

Robert Gorringe

Forensic dentistry has come under fire in recent years after multiple cases where the odontological evidence pointed to the wrong man. Most notable is that of Ray Krone, dubbed the “Snaggletooth Killer,” who was given the death penalty and then exonerated by DNA evidence 10 years later.

In the late 1970s, forensic dentistry became popular in the US after it helped convict Ted Bundy. In Britain, however, it was readily used decades earlier, having been pioneered by pathologist Keith Simpson. One of the first recorded instances of forensic dentistry evidence in an English court came in 1948 during the trial of Robert Gorringe.

Gorringe was accused of killing his wife, Phyllis. After inspecting her body, Simpson found bite marks on her breasts and was able to match them to her husband. Robert Gorringe was convicted and executed.

7 Body Decomposition

Higgins Brothers

In 1911, six-year-old William and four-year-old John Higgins were killed by their father, Patrick Higgins, and dumped in a flooded quarry. Eighteen months later, their bodies resurfaced, surprisingly well-preserved. Through hydrolysis, the bodies had undergone saponification, where body fat is transformed into a soap-like substance called adipocere.

Pathologist Sydney Smith and surgeon Harvey Littlejohn inspected the bodies and could even tell that the boys’ last meal was broth—although they had eaten it 18 months prior. The physical evidence secured Higgins’s conviction.

This case has gained publicity in recent times because Smith and Littlejohn secretly removed parts of the bodies (including the heads) without police permission so that they could continue studying this unique aspect of body decomposition. Today, we know that numerous external factors can affect body decomposition. There are even body farms dedicated to studying these effects.

6 Facial Composites

Harvey Glatman

Suspect sketches have been in use for over 100 years. However, it takes a long time—and artistic talent—to draw a sketch by hand. So it’s no surprise that police wanted a better way of quickly assembling a composite.

Several people claim credit for the concept, but Smith & Wesson put such a system, the Identi-KIT, into commercial production. Consisting of several sheets, it featured a variety of facial features that could be stacked on top of each other. Therefore, any officer could assemble a composite in just a few minutes.

The Identi-KIT proved its worth in 1958 when it helped police to apprehend Los Angeles serial killer Harvey Glatman. Dubbed “The Glamour Girl Slayer,” Glatman lured women with the promise of a modeling career and took photos before killing them. After his conviction, the Identi-KIT quickly phased out hand-drawn sketches.

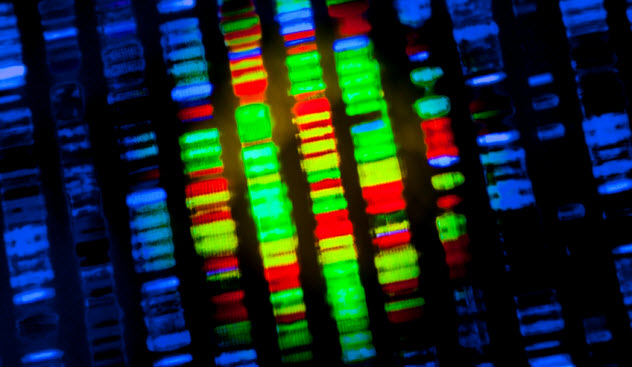

5 DNA Profiling

The Southside Strangler

DNA profiling was invented in 1984 by Sir Alec Jeffreys in Leicester. When the wrong man was being investigated for a double homicide in 1987, DNA testing proved effective by pointing the finger at Colin Pitchfork, the first criminal caught using DNA profiling.

The technique made its way across the pond quickly and secured an arrest in a sexual assault case that year. The big breakthrough came just a few months later, though, when Timothy Wilson Spencer was caught with the help of DNA fingerprinting.

Dubbed the “Southside Strangler,” Spencer had raped and murdered at least four women in Richmond, Virginia. He became the first US murderer convicted with DNA evidence and was executed in 1994. Virginia soon opened the first DNA lab in the country.

4 Entomology

Lydney Murder

The first recorded use of forensic entomology dates back to 13th-century China. In The Washing Away of Wrongs, the author tells how he found a sickle to be the murder weapon thanks to flies attracted to minute samples of dried blood.

At the end of the 19th century, entomology had been used in several murder cases. But the results were too widespread for the discipline to become an investigative standard. However, in 1964, the Lydney murder proved the value of forensic entomology conclusively.

A body was found in the woods near Bracknell, Berkshire, seemingly having decomposed for almost a month. However, entomological evidence suggested that the time of death was 9–12 days earlier with the rate of decomposition accelerated due to hot weather. With this information, the body was identified as Peter Thomas and his business partner, William Brittle, was convicted of murder.

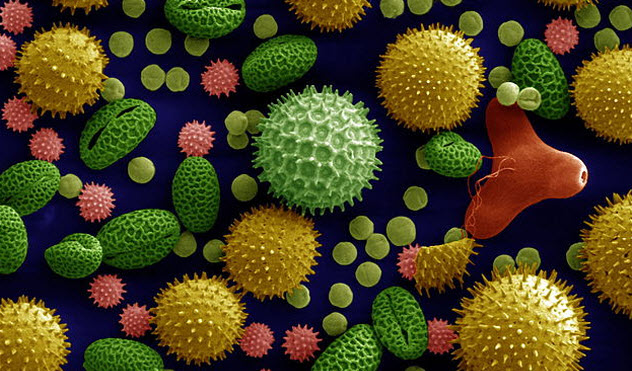

3 Palynology

Austrian Murder

Palynology, the study of spores and pollen, has its forensic uses but lacks the global awareness of other disciplines. It also has only a handful of experts worldwide.

The first recorded use of forensic palynology happened in Austria in 1959 and remains, arguably, its most successful application. Austrian police were looking for an unnamed man who had disappeared near Vienna. They were fairly certain that he’d been murdered and had a likely suspect. However, they lacked evidence tying the suspect to the crime.

Enter palynologist Wilhelm Klaus. Analyzing a mud sample from the defendant’s boots, he found modern pollen from spruce, willow, and alder trees as well as 20-million-year-old hickory pollen grains from eroded rock sediments dated to the Miocene epoch. There was just a small area 20 kilometers (12 miles) north of Vienna that fit the bill. Presented with this information, the suspect confessed his crime and took police to the body.

2 Toxicology

Gross Family

Alexander Gettler, one of the pioneers of forensic toxicology in the US, often had to devise his own tests to get results. That was the case in 1935 when he became the first person to use a spectrograph in a criminal investigation.

Frederick Gross was charged with killing his family. Over the course of weeks, his wife and four of his five children had died, seemingly poisoned by thallium. Gross was the only unaffected one in the family. Obviously, police suspected him and even found the murder weapon—a box of cocoa with traces of thallium.

Gettler decided to use a spectrograph to detect thallium’s unique signature in the cocoa. Instead, he found traces of copper from the box. A closer inspection of the bodies revealed that the children had thallium in their systems, but the mother didn’t. She had poisoned the children and coincidentally died of undiagnosed encephalitis.

1 Postmortem Examination

The Hay Poisoner

Autopsies have been carried out since ancient times, including on Julius Caesar. Over the course of millennia, the techniques have improved and so has the information obtained from autopsies.

One infamous case involved Major Herbert Rowse Armstrong (aka the “Hay Poisoner”). In 1921, he killed his wife, Katharine, with arsenic. Initially, he got away with it. But Armstrong’s mistake was trying the same thing months later. This time, he targeted a rival solicitor who fell ill but survived. Armstrong was charged with his attempted murder and became a suspect in his wife’s death.

Britain’s leading pathologist Bernard Spilsbury did the postmortem examination on Katharine Armstrong, who had been buried for 10 months by that time. Even so, Spilsbury found that large amounts of arsenic had been administered within 24 hours of her death. The major was found guilty and executed.