Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Early Special Effects That Made Movie Magic

By the end of the 1930s, all but computerized cinematographic special effects had been discovered or invented. Although standard among the techniques of today’s filmmakers, each and every one of the early special effects was a marvel to the original audience. Motion pictures, to no small degree, owe their success to moviegoers’ delight in the seemingly marvelous feats these illusions produce.

10Stop-Action Substitution

The first special effect occurred in the 18-second 1895 film The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. The Edison Library film shows Mary (portrayed by Robert Thomae, Kinetoscope Company’s secretary and treasurer) kneeling at the chopping block. She extends her neck, peering ahead. The executioner, amid a company of onlookers holding pikes, lifts his axe. Bringing it down swiftly, he chops off her head, which tumbles forward, off the block, and rolls on the ground. After a moment, the executioner picks up her head by the hair and displays it.

The film’s special effect is the stop-action substitution of a mannequin for Thomae. When the film resumes, the dummy loses its head, but since the audience is unaware that the film has been stopped and the substitution has been made, it appears to them that Mary has been beheaded.

9Split-Screen Masking

Early master of cinematographic special effects Georges Melies, playing the part of a chemist, used split-screen masking to make his head explode in his Star Film Company’s 2-minute 25-second 1902 French fantasy film The Man with the India Rubber Head.

After several preliminary preparations, the chemist draws a clone of his own head from a wooden box, setting it atop a small table he has placed on a larger table. He attaches a bellows to a pipe connected to the underside of the smaller table. Pumping the bellows, he forces air through the pipe, into the head, which becomes larger and larger. Finally, the chemist closes a valve on the pipe and detaches the bellows, allowing the head to deflate.

Working the instrument with enthusiasm and vigor, an assistant gets carried away, and the head expands until it explodes in a thick cloud of white smoke, which knocks the assistant off his stool and the chemist off his feet. When they manage to stand, the scientist grabs his assistant by the arms and flings him from the room, delivering a parting kick to his posterior.

8Double Exposure

After making his own camera, George Albert Smith, an English filmmaker, patented the double exposure in his own country. He used this technique to create the ghost that appears in his 1909 film The Corsican Brothers.

In the short film, the ghost of a man appears to his twin brother to show the brother a vision of how he died in a duel.

7Miniatures

In 1899, the Windsor Hotel in New York City burned to the ground but not before many guests, trapped on the building’s upper floors, jumped to their deaths or perished in the intense flames. Some who slid down ropes fell to their deaths when friction produced burns too hot to bear. Although firefighters rescued some guests and sought to save others by deploying ladders, the fire burned too fast for them to reach all the windows. In all, 45 people are known to have died in the fire, and 41 others were listed as “missing.”

The fire was the subject of a short 1899 Vitagraph film, The Windsor Hotel Fire by Albert E. Smith and J. Stewart Blackton. Tiny victims fell from miniature buildings made of cardboard while squirt guns acted as fire hoses.

6Frame Tinting

In some prints of his 12-minute, silent black-and-white 1903 film The Great Train Robbery, Edwin S. Porter tinted three frames red and green to suggest the firing of a gun.

In the first or last scene of the film (the sequence could be placed in either location, as either a prologue or an epilogue), Justus D. Barnes, the bandits’ leader, aims at the camera, seeming to fire at the audience.

In those copies of the film that are tinted, the effect is subtle. As the gun fires, the surrounding darkness illuminates enough to show the colors of the Barnes’s shirt (green) and neckerchief (red, with white polka dots). The result creates a subliminal effect that heightens the thrill.

5Glass Shot

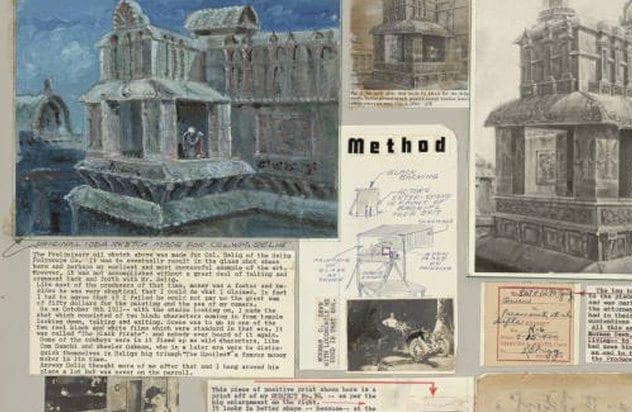

Norman O. Dawn created 861 special effects, many of them refinements of the in-camera matte shot. Some of his work is cataloged in a collection of 164 cards. Designed by Dawn himself from his own notes and records, the cards bear photographs, paintings in oil and watercolor, illustrations, and explanatory text. Each card displays the date, the effect number, a title, and the author’s byline.

Effect number 23, dated October 1911, explains how Dawn created a glass shot for The Black Pirate. He began the effect, as always, with a painting. It showed a room in a temple, which was visible through a window. Once the painting was approved, it was transferred to glass and embellished, as a matte. Part of the painting was blacked out, so the live action of the actors could be filmed on a second exposure of the film. The finished result shows the actors performing against the background painting on the glass (the matte), with no indication that they were added to the film, so that the two shots appear to be one.

4Props

Not all special effects involve trick photography. Others include makeup, live or mechanical effects such as the use of smoke generators, electrical effects, and sound effects. The term prop, which is short for “property,” refers to any theatrical or cinematographic object that an actor uses during the course of a performance.

The use of theatrical props is ancient. However, cinematographic props were introduced in the early days of film. Notable examples are the props Mack Sennett employed in the Keystone Kops films produced between 1912 and 1917, which include “rubber bricks, collapsing telegraph poles, fake houses, car crashes,” and a “special patrol wagon.”

3Schufftan Process

Fritz Lang’s two-hour, 33-minute 1927 film Metropolis is known for its use of the Schufftan Process. This effect requires a motion-picture camera, a mirror that has both a reflective and a transparent surface (part of the mirror from which the reflective surface has been removed), a scale model or matte painting, and live actors performing on a set.

The reflective portion of the mirror and its transparent portion are positioned at an angle between the camera and the live-action sequence. The reflective portion of the mirror reflects the model or the painting, which is filmed by the camera. At the same time, the camera also shoots the images of the live action on the set, which show through the transparent surface of the glass.

As a result, the model or painting is combined with the live action in a seamless unity. In this way, Lang combined the live performances of the actors with the matte paintings, models, and miniatures that created the otherworldly appearance of the futuristic city’s architecture, infrastructure, and mood.

2Rear Projection

Today, rear projection is used in many motion pictures. It even appears, on a daily basis, on television weather reports. The effect is impressive, if simple, and appears in some of the earliest films. King Kong includes numerous types of special effects, including stop-motion, miniatures, puppets, and rear projection, sometimes employing several at once.

In one sequence, Kong crosses the screen, in the background. Turning, he moves forward, toward the camera. To accomplish this feat, two cameras were used. The rear-projection camera projected a mirror image of its film onto the rear-projection screen as the forward camera recorded the projected image. At the same time, the animated model of Kong marches across the scene behind the rear-projection screen and is recorded with the images projected by the rear-projection camera by the front camera. The effect suggests Kong is part of the rear-projected images.

The special effects, particularly those involving stop-motion animation, were largely the work of Willis O’Brien and his assistant Buzz Dixon.

1Combination

1939’s Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz are cinematographic masterpieces. Nevertheless, both motion pictures lost that year’s Academy Award for best special effects.

Filmed on location in Balboa Park, California, The Rains Came had a budget of $2,500,000. $500,000 was set aside for the flood and earthquake scenes, which required the labors of 350 workers and over a month’s labor. A 50,000-gallon tank was built on the sound stage.

The shot of the bursting dam was filmed during two nights and required the use of 14 cameras. Filming the rain and flood sequences took almost 50 days and 33 million gallons of water.

The dam was a miniature model; the fleeing crowd was composed of extras. Matte paintings were combined with live-action sequences to show the flood washing away a bridge and drowning its occupants. Traveling mattes allowed water to swell and rush through spaces occupied by actors and falling, demolished miniatures.

Gary Pullman lives south of Area 51, which, according to his family and friends, explains “a lot.” His 2016 urban fantasy novel A Whole World Full of Hurt was published by The Wild Rose Press. An instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, he writes several blogs, including Chillers and Thrillers: A Blog on the Theory and Practice of Writing Horror Fiction and Nightmare Novels and Other tales of Terror.