Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Hilarious First Descriptions Of Things We Take For Granted

Our world is a strange place full of incredible things. We take a lot of that for granted. We’ve seen all the weirdness of our world for so long that we no longer feel that sense of amazement it deserves.

There was a time, though, when the things we now consider normal were completely unknown. The people who got to experience these things for the first time had no idea what they were about to see—or how to explain it to everyone back home.

10 An Explorer Thought Gorillas Were Just Very Hairy People

About 2,500 years ago, Hanno the Navigator became one of the first Europeans to see a band of gorillas. He had been sent off to explore Africa and had gotten used to bumping into strange and exotic tribes.

So when he found an island full of gorillas, he figured that they were just the funniest-looking group of people yet. Hanno wrote that he’d found “savage people, the greater part of whom were women, whose bodies were hairy, and whom our interpreters called Gorillae.”

He and his men tried to introduce themselves to the gorillas, but the gorillas weren’t too communicative. Instead, the apes just threw stones at the humans and ran away. Hanno’s men caught three of the gorillas and tried to talk them into going back to Carthage with the men. Unfortunately, Hanno said, the gorillas “could not be prevailed upon to accompany us.”

When the gorillas got violent, Hanno and his men killed them. Then Hanno went a little crazy. “We flayed them,” he wrote, talking about what he thought were human beings, “and brought their skins with us to Carthage.”

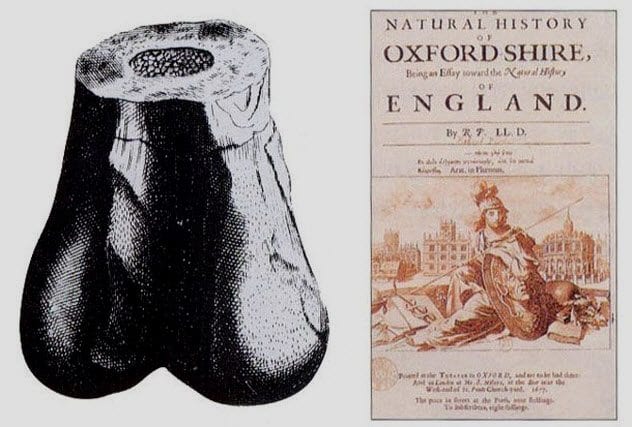

9 The First Dinosaur Bone Was Believed To Be Goliath’s Leg

When Robert Plot found the first dinosaur bone, it was, as you can imagine, a pretty baffling experience. He had no idea what he was looking at except that it was huge, terrifying, and unlike anything he’d ever seen.

Plot was determined to get to the bottom of it, so he took the bone to an elephant in 1676 to see if it matched. “I compared ours,” he wrote, “and found those of the elephant not only of a different shape, but also incomparably different to ours.”

Plot was sure that there was only one explanation. “They must have been the bones of men or women,” he wrote. Ever a believer in giants, he argued that “there have been men and women of proportionable stature in all ages of the world.”

This bone, Plot believed, was proof that every giant story he’d ever heard was true. “Goliath for certain was [297 centimeters (9’9″)] tall,” he wrote, before filling pages with lists of every giant story he’d ever heard.

“These bones from Cornwell might be the bones of a man or woman,” he concluded. ” ’Tis plain.”

8 Galileo Said Saturn Had Ears

Galileo was the first person to spot Saturn’s rings. This happened, though, in 1610, and telescope technology still had a long way to go. When he looked at Saturn, Galileo wasn’t looking at one of those crystal clear images we see from NASA. He was looking at a blurry light and making out what he could. And so it’s understandable that he thought he was looking at a star with ears.

It actually took him three years of analysis to decide that Saturn had ears. At first, he figured he was looking at three stars that were just very close together. “The star of Saturn is not a single star, but is a composite of three,” Galileo wrote, “which almost touch each other, never change, or move relative to each other.”

Two years later, he got a bad angle and couldn’t make out the rings anymore. Not realizing that he was just having a problem with his telescope, Galileo was sure that the other two stars had magically vanished. “I do not know what to say in a case so surprising, so unlooked for, and so novel,” he wrote. “Has Saturn swallowed his children?”

When they showed up again the next year, Galileo changed his view. After three years of observation, he now knew that Saturn was not three evanescent stars. It was a single celestial body—and, Galileo declared, it had “ears.”

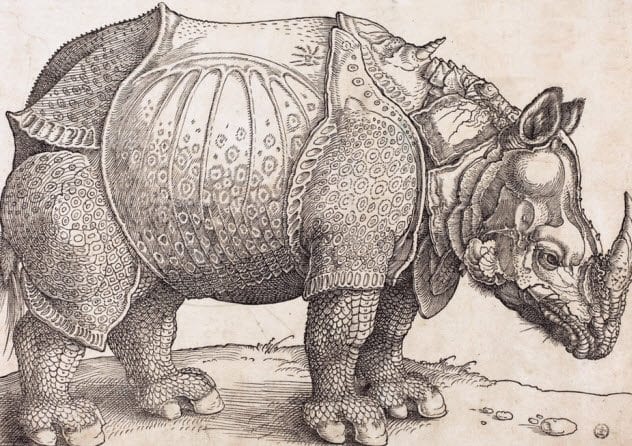

7 The Best-Known Picture Of A Rhinoceros Showed It In Metal Armor

When he drew a rhinoceros in 1515, Albrecht Durer had never seen one. A rhinoceros was making a tour around Europe, but Durer didn’t get the chance to see it himself. Instead, Durer just read a few descriptions and figured that he had enough of a handle on it to draw it.

He sketched the picture you see above and wrote on it proudly, “This is an accurate representation.” A rhinoceros, Durer declared, “is the color of a speckled tortoise and is almost entirely covered with thick scales. It is the size of an elephant but has shorter legs and is almost invulnerable.”

His picture had the rhinoceros actually wearing a metal breastplate like a medieval knight. He’d thrown an extra horn onto its back and added scales on its legs. Sure, it wasn’t 100 percent accurate. But for centuries, his picture showed up in books and schools, accepted as the definitive anatomical drawing of a rhinoceros.

6 The First Description Of A Tornado Is Surprisingly Heartless

Tornadoes have hit places outside North America but never with quite the ferocity and frequency with which they ravage the United States. So the oldest description we have of a tornado comes from John Winthrop, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in 1643. And it’s kind of messed up.

“There arose a sudden gust,” Winthrop’s description begins. “It blew down multitudes of trees. It lifted up their meeting house at Newbury, the people being in it. It darkened the air with dust.”

When he gets to the damage report, though, we get a clear glimpse into how Winthrop viewed human life. “Through God’s great mercy, it did no hurt,” he celebrates, before adding inconsequentially, “but only killed one Indian.”

The Native American was crushed by a falling tree—which, according to Winthrop, was a near-disaster averted. After all, that tree had nearly hit a white person. Relieved, Winthrop allowed himself to contemplate the worst. Thanking God that it had only killed a Native American, Winthrop noted that the tree “was straight between [the settlers] Lynn and Hampton.”

5 The First Explorer To Australia Called It ‘No Good’

Long before James Cook was born, the Dutch made it to Australia. Led by Willem Janszoon, a team of explorers sailed south and made it to Australia. Janszoon thought he was exploring New Guinea. He had no idea he’d discovered a whole new continent—and he didn’t particularly care for it.

“Vast regions were for the great part uncultivated,” Janszoon wrote, “and certain parts inhabited by savage, cruel, black barbarians.” It’s a description that seems horrible today. But to be fair to Janszoon, nine of his men had been murdered and cannibalized in the short time that he’d been in Australia.

They gave up on Australia and turned back, writing off an entire continent by saying that there was “no good to be done there.” People took his advice.

A few years later, an official recommendation was sent out to stay away from the place where Janszoon had landed. “Such discovery was once tried about the year 1606,” the report said. It did not recommend trying it again.

4 The First Description Of A Kangaroo Came From The Wrong Country

“An extraordinary animal inhabits these trees,” begins the first description ever made of a kangaroo. “The muzzle is that of the fox, while the tail resembles that of a marmoset, and the ears those of a bat. Its hands are like man’s, and its feet like those of an ape. This beast carries its young wherever it goes in a sort of exterior pouch, or large bag.”

It’s a normal enough description of a kangaroo except for one thing. It was written in 1511—nearly 100 years before the first European landed in Australia.

The writer, Peter Martyr, was describing a creature he’d seen firsthand. It had been brought to him by the crew of Vicente Yanez Pinzon, a man who had accompanied Christopher Columbus and who—by all records—had never gone to Australia.

Martyr wrote this in a letter to Cardinal Ludovico d’Aragon. Martyr also stated that the cardinal had analyzed the creature. They never give the animal a name, but Martyr’s description certainly fits the kangaroo: “This animal never takes its young out of this pouch, save when they are at play or nursing, until the time comes when they are able to fend for themselves.”

Does this mean that Pinzon reached Australia? Or does it mean that there were kangaroos in Central America? It’s not 100 percent clear, but there’s even more proof that a kangaroo made it to Europe before Janszoon’s trip. On a piece of paper, sometime around 1580, a Portuguese writer sketched a kangaroo inside the letter “D.”

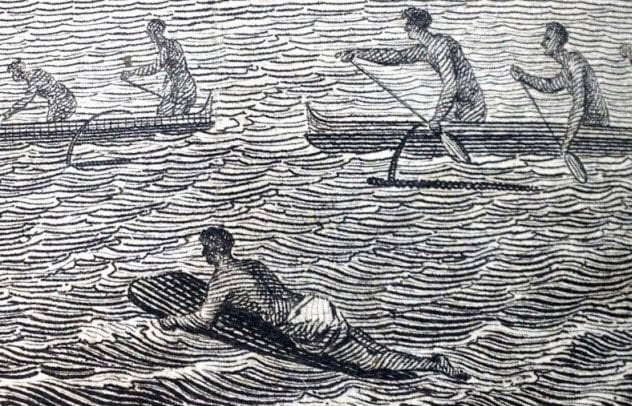

3 The First Description Of Surfing Calls It The ‘Most Supreme Pleasure’

When James Cook made it to Hawaii in 1778, he and his crew became the first Europeans in history to see someone surf. They watched native men on surfboards and in canoes ride the waves—and they thought it was the greatest thing they’d ever seen.

William J. Anderson, the ship’s surgeon, gushed about it. He’d watched a man paddling a canoe instead of riding a surfboard, but the man was certainly riding waves.

“He went out from the shore, till he was near the place where the swell began to take its rise,” Anderson wrote, “and watching its first motion very attentively, paddled before it, with great quickness, till he found that it overtook him, and had acquired sufficient force to carry his canoe before it, without passing underneath.”

Anderson loved it. “While he was driven on, so fast and so smoothly, by the sea,” he wrote, “I could not help concluding that this man felt the most supreme pleasure.”

2 Columbus Described The Native Americans As Pushovers

After landing in America, Christopher Columbus wrote a letter to King Ferdinand of Spain, letting the king know what Columbus had discovered. In case you still have any lingering doubts about Columbus, the letter makes it pretty clear that he was a terrible human being.

“I found very many islands, filled with innumerable people, and I have taken possession of them,” Columbus declared. “No opposition was offered to me.”

The natives he met were, by and large, described as generous people who didn’t even try to stop Columbus from taking everything they had. “They refuse nothing that they possess, if it be asked of them,” Columbus wrote. “They are content with whatever trifle of whatever kind that may be given to them, whether it be of value or valueless.”

He ends his letter by promising that he will be able to give the kingdom “as much gold as they may need” and “slaves, as many as they shall order.”

1 George Shaw Thought That The Platypus Was A Hoax

The first written description of a platypus comes from George Shaw in 1799. Someone had sent him a specimen from Australia to examine. Looking at a duck-billed platypus for the first time, Shaw was pretty sure that these people were just conning him.

“It naturally excites the idea of some deceptive preparation by artificial means,” Shaw wrote about the animal, which he described as an “otter in miniature” with a duck beak “engrafted on the head.”

Shaw didn’t believe it was real until he’d given it “the most minute and rigid examination.” He wrote up a full report on the platypus, concluding that it likely dug, swam, and ate aquatic plants. Then Shaw completely gave up on figuring out anything else about the weird creature in front of him.

“That,” a befuddled Shaw wrote, “is all that can at present be reasonably guessed at.”