Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Odd Ways Peter The Great Forced Russia Into The Enlightenment

Before Peter the Great, who ruled from 1682 to 1725, Russia was lagging years behind the rest of the world. While the Enlightenment was bringing the European world into a new age, Russia was stagnant, until Tsar Peter I dragged it kicking and screaming into the modern world.

Peter the Great did some incredible things for Russia, but he was mainly working off the idea that if the Europeans were doing something, Russia should be doing it, too. And that led to some absolutely insane decisions.

For better or for worse, Peter the Great brought Russia into the modern world—but he did it in some of the strangest ways possible.

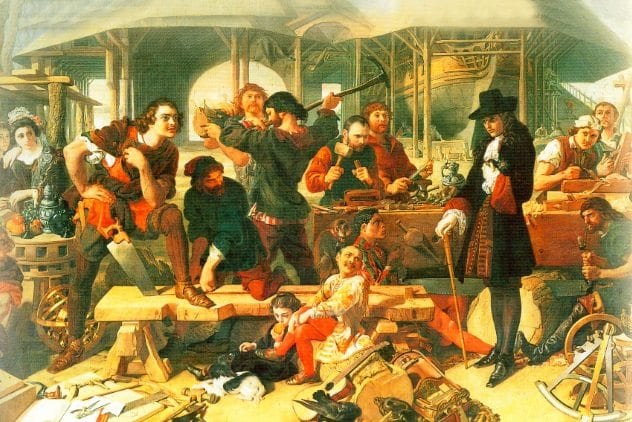

10 The Terrible Disguises Of Peter The Great

Peter the Great was determined to make Russia a nation that rivaled the greatest European powers. He wanted Russia to do everything the Europeans did. First, though, he had to figure out what that was. So, Peter decided to make a tour of Europe—in disguise.

It was a fine idea, in theory, except that Peter was 203 centimeters (6’8”) tall. The man towered above every person he saw, and he traveled with an entourage of 250 Russian nobles. So when a gigantic, wealthy Russian man walked around telling people he was a migrant laborer, absolutely nobody was fooled.

The tsar spent months working as a shipbuilder in the Netherlands. He told his employer that he was a foreign craftsman. They didn’t believe him. Everybody knew who he was. But, mostly for the novelty, they let Peter work there, anyway.

Whole crowds of Dutch citizens would come out to watch Peter the Great building ships and living in peasant quarters. As a man who grew up in a castle, he was probably doing the worst job at it that they’d ever seen. He worked as a laborer long enough to help build a ship. If he didn’t realize that his disguise wasn’t working by then, it must have hit him when his boss asked if he wanted the ship sent to his palace.

9 The Beard Tax

When Peter the Great returned to Russia, he was determined to make some changes. From there on out, they were going to do things the European way, and Peter wasn’t going to waste any time. During the reception to welcome him home, Peter hugged his noblemen. Then, without a word of warning, he pulled out a razor and chopped off their beards.

Having a beard became a crime shortly after. This was a major a change: Until then, Russian had viewed a long, flowing beard as a sign of manliness. But the Europeans had made fun of Peter for his, so the beards had to go.

Anyone with a beard had to pay a tax of 100 rubles each year. Peasants and clergyman were excepted, but if a peasant entered a city with beard, he paid a fine. People who paid the tax were given a coin that read, “The beard is a useless burden!” to let the police know they were legally permitted to have one. If they were caught without the coin, the police could forcibly shave them on the streets.

For all of his hatred for beards, though, Peter the Great loved mustaches. For the men of the Russian military, he set out another decree: Beards were forbidden, but mustaches were mandatory.

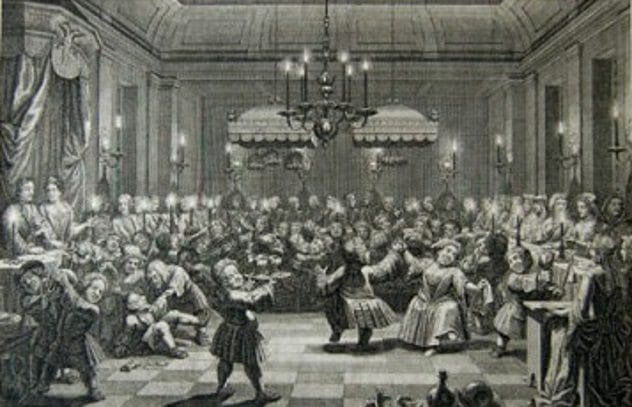

8 The All-Joking, All-Drunken Synod Of Fools And Jesters

Up until then, the Russian Orthodox Church had been led by the patriarch of Moscow. Peter the Great changed all that. He was a raging drinker and partier, and he didn’t care for all the pious stuff. So he replaced Russia’s religious leaders with a new group called the Holy Synod, filled with people he could control.

He didn’t particularly respect his own church, either. Around the same time, he set up another group called the All-Joking, All-Drunken Synod of Fools and Jesters, and their job was to get as drunk as possible as often as they could. This was Peter’s old drinking group, now reformed to let the church know exactly what he thought of it. He even made one of his friends the “prince-pope” of the All-Drunken Synod and had him do a mock Stations of the Cross before they all got hammered.

People weren’t thrilled. Some started to say that Peter the Great was the antichrist himself. But the people in power didn’t mind. Eventually, every powerful man in the government was part of the All-Drunken Synod—including some of the clergy.

7 The Medal Of Drunkenness

Peter the Great might have been a raging alcoholic, but he didn’t want Europeans coming to Russia and seeing drunken peasants sleeping on the streets. He was determined to fix the drinking problem—in the silliest ways possible.

Anyone caught on the streets intoxicated was forced to wear an 8-kilogram (18 lb) cast iron medal around his neck for the next week. It looked exactly like a medal of honor, except that it read “For drunkenness,” and it was incredibly heavy.

The Medal of Drunkenness didn’t do much to curb alcoholism in Russia, but Peter probably wasn’t too worried. His other rules made it pretty clear that he thought getting drunk was a God-given right. In another law, Peter decreed that a woman could be flogged if she made her husband leave the tavern before he was done drinking.

6 The Museum Of Deformities

In Europe, Peter the Great had seen countless cabinets of curiosities. These were the era’s freak shows, and he found them incredibly fascinating. Putting freaks on display, he believed, was a scientific and educational tool that would enrich the country, so he had a museum built as soon as he got back.

His museum was called the Kunstkamera, and it was full of the strangest things he could find. It had two-headed babies preserved in jars, deformed animal skeletons, and more. It even held live exhibits where children with birth defects would meet and greet the visitors.

For Peter, it wasn’t just exploitation. It was education. When he opened it, he declared, “I want people to look and learn!” The press agreed. In France, the papers spread the news about his museum of oddities. Impressed, they wrote, “Tsar Peter Alexeyevich is intent on enlightening his country.”

5 Mandatory Pants

In this era, Russia still wore its traditional clothing. The men would step out dressed in long, thick robes with tall hats on their heads—until Peter the Great forced them to put on some pants. “No one,” Peter declared, “is to wear Russian dress.” From that day forward, it was law: “Western dress shall be worn by all!”

Every piece of clothing was dictated. There were laws on what type of underwear you could wear. There were punishments in place for wearing shoes in the bed. Men were required to wear French-cut coats with German-cut clothes underneath, and they could be punished if they didn’t.

Like his beard tax, Peter introduced his mandatory pants laws by pouncing up behind unsuspecting noblemen and cutting the sleeves off their robes. Then he laughed at them and said, “Now you won’t be dragging your clothes through your food!”

He certainly changed fashion, but it wasn’t exactly well-thought-out. Those thick cloaks had kept Russians warm through the winter. Now, dressed in German underwear, they were struggling not to freeze to death.

4 The Russian Flag

The modern Russian flag was Peter the Great’s creation, too. It’s a bold but simple design: three stripes, with white above, red below, and blue between, colors carefully chosen to symbolize . . . uh . . . absolutely nothing.

Russia got its flag because when Peter was in Europe, he was delighted by the way Dutch ships had little flags on them. Russian ships, he decided, needed to have little flags on them, too. He didn’t really know what to hoist, though, so he just moved the colors on the Dutch flag around and had his ships use that as their flag.

At first, the new flag was only used on ships, but in time, it turned into the country’s national flag. Soon, the whole country was marching under those three colors, most unaware that the patriotic symbol of their nation was just an old emperor trying to be like the Netherlands.

3 The Construction Of St. Petersburg

St. Petersburg, too, was just another attempt to copy the Dutch. Peter the Great ordered his men to build the city on top of a swamp and demanded that it look as much like Amsterdam as possible.

His dream was to make it Russia’s most European city. He even imagined that people would travel around St. Petersburg by drifting down the canals in boats, like in Venice. And he was willing to work his people to death to get it.

One of the first buildings constructed in the city was the Peter and Paul Fortress. Over 20,000 laborers worked on it, some being required to work with their bare hands. Thousands of people died building it.

To make sure he had enough stone, Peter made it illegal to build any stone buildings anywhere in Russia other than St. Petersburg. All stones, Peter demanded, were to be sent to the city.

Peter was thrilled with the result. He even made St. Petersburg the capital of the nation. Others, though, were less impressed. Dostoyevsky, for one, called it the “most artificial city in the world.”

2 Mandatory Nicotine Habits

Tobacco had been banned by the previous tsars. The Russian Church viewed smoking as an “abomination to God,” and they dealt with it severely. A person caught smoking could be exiled to Siberia or worse. Some had their nostrils torn open or their lips cut off to keep them from ever smoking again.

Peter the Great, though, took a different approach. He didn’t just legalize smoking—he insisted on it. Every Russian was encouraged to smoke as often as possible. Some members of the nobility were even required to smoke under the decree of the tsar.

As with everything else Peter did, smoking was something he’d seen the Europeans do. It was also an opportunity to get them into the country. He let foreign companies set up tobacco plantations in Russia and started building tobacco-manufacturing plants around the nation.

Cigarettes, though, are never complete without caffeine, so Peter brought coffee to Russia, too. The Russians thought it was disgusting. They called it “smut syrup,” but Peter pushed it hard enough that pretty soon, there were enough coffee drinkers to open Russia’s first coffee house.

1 The Dwarf Wedding

Peter the Great loved people with dwarfism. In his time, treating little people like jesters was normal, but he took it to extremes. He would get little people to hide naked inside pies and then jump out to surprise people for a laugh.

He wanted more dwarfs—so he tried to breed them. He had a little person in his court, Iakim Volkov, married to another dwarf, hoping to breed a race of little people. But he wanted it to be a big affair. He ordered every little person in Russia to attend.

About 70 little people made it, and he dressed them all in the latest Western fashions, lined with gold. This wasn’t a gesture of respect. Most of these dwarfs were poor, uneducated peasants. His attendants deliberately loaded them up with alcohol and then laughed while the peasant dwarfs clumsily stumbled through dances and erupted into drunken fistfights.

Peter thought it was hilarious—but more than that, he thought it was an allegory for Russia. Russia, he believed, was like those drunken little people. They had the clothes, and they were doing the dances, but they were just playing at being Europeans.