Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Top 10 Crazy World War II Food Substitutes

War used to be fairly simple. There was a campaign, the armies fought each other, and the country that lost gave up. The average person on the street barely knew that a war was going on! But then the 19th century rolled around—and bam!—we had total war.

As a result, entire countries, not just armies, were legitimate targets. World War II was a total war, so navies thought nothing of attacking ships carrying food—even if the food was destined for civilians. The goal was to starve the enemy, disrupting public life and damaging the country as much as possible.

10 Food Inventions That Changed The Way We Eat Breakfast

This kind of warfare quickly led to food shortages. To alleviate the problem, the UK and U.S. governments rationed the amount of food each person could buy. Naturally, some foods disappeared from the dinner table for years.

Since many luxury ingredients were either impossible or hard to find, people resorted to some frankly weird substitutes, which we’d barely consider eating today. Here are 10 of the best. Bon appetit!

10 Potato Pastry

We all like to indulge our sweet tooth from time to time, and wartime folks were no different. There was a problem, though. To make the sweet things they liked to eat—pies, cakes, and such—they needed butter, eggs, and flour. All three had been replaced by rationed wartime substitutes. To make their ingredients go further, they filled their dough with potatoes.

The British government was keen to encourage people to use potatoes because they were easy to grow. The authorities put out leaflets containing recipes for everything from the normal baked potato to the weird potato biscuits and potato pastry.[1] There were even potato piglets, an alternative to sausage rolls.

Potato pastry, which was meant to be a pie pastry, usually contained margarine, flour, potato, and salt. Even simpler recipes were available for those who had basically nothing. Potato pastry could be made with just flour, salt, potato, and “fat.” The chef was urged to use this pastry immediately because it would become very dry if reheated. Yummy!

9 War Cake

Continuing with another sweet dish—people do love their desserts—that developed from rationing. Without ingredients like sugar, eggs, and milk, what was the home baker to do?

Be creative!

Home cooks got crafty and created a bunch of makeshift recipes for popular dishes, using ingredients like applesauce, molasses, or lard to stand in for the usual fats and sweeteners, and deploying lots of common spices to mask the taste.

There were several options for dessert that emerged from the rationing in WWII. Apple Brown Betty was a popular option as it used old or stale bread crumbs and maple syrup instead of sugar. Baked custards were also adapted, based on what items were being rationed that week.

War Cake or Ration Cake was a popular option as it required no eggs, milk, or butter. With only a few essential ingredients and some spices, this cake recipe was easy to make. It originated in Canada before making its way to the United States and Britain. Try making your own War Cake tonight—here’s the recipe. Happy Baking!

Mix 2 cups sugar, 2 cups hot water, 3 tablespoons lard, 1 teaspoon salt, 1 teaspoon each of cloves and cinnamon, and 1 package seedless raisins. Boil all ingredients together for 5 minutes and let cool. Then add 2-3 cups flour with 1 teaspoon baking soda dissolved (in 1 tablespoon water). (You can also add 1 teaspoon baking powder.) Bake for one hour in a slow oven (about 300-325°).[2]

8 Fanta

Fanta is one of the world’s most popular sodas, beloved for its orange flavor and its colorful, happy style. Coca-Cola made this version in Italy in 1955, and it quickly became popular across Europe. But the original Fanta was made in 1940, and its story is a little darker.

Coca-Cola exploded in Germany during the 1930s, going from sales of 100,000 cases a year to just over four million by the end of the decade. The company’s German branch was becoming one of its greatest success stories. But that would change with the outbreak of war.

The Allies embargoed Germany, and shipments of the essential Coca-Cola syrup from America dried up, with supplies eventually running out. By this time, Coca-Cola Germany had been cut off from the main company in the U.S., and it needed to sustain itself.

In a last-ditch effort, they launched a new drink made of whey, apple fiber, and beet sugar. Not exactly as appetizing as Coca-Cola, but in a desperate wartime Germany, it was good enough.

The new drink was named Fanta, short for Fantasie, the German word for “imagination.” The drink sold extremely well, with three million cases shipped in 1943. Most Germans used it for cooking because sugar was heavily rationed. It was discontinued when the war ended, which tells us just how bad it probably tasted.[3]

7 National Loaf

In Britain, most bread at the time was made with Canadian wheat, which had to be shipped across the Atlantic. This wheat took up cargo space that could have been used for more important things, like munitions.

In 1942, the British government banned white bread outright. In its place, they introduced a new kind of bread called the “National Loaf.” It was made mostly using wheat grown in Britain. The British wheat was less refined, which helped it go further. Parts of the plant that were usually taken out, like the bran, were left in, giving the bread a rough texture.

The National Loaf was so bad that the British public called it “Hitler’s secret weapon.” The government put out propaganda to get people to like it. A rumor that the bread increased people’s sex drives was almost certainly spread on purpose.[4]

On top of being smaller than prewar loaves, the National Loaf was gray in color and had a texture like sawdust. The crust was tough, and the bread itself was hardly ever fresh.

Despite this, it was much healthier than the white stuff. In fact, when the government finally reintroduced white bread eight years later, some people protested that the National Loaf should be kept for health reasons.

6 Dripping

During the war, Europe and America suffered a fat shortage. This might sound like a good thing, but it was a huge problem when people were already struggling to get enough fat and calories. Most of the world’s cooking fats were made in East Asia and Africa, which were inaccessible when German U-boats dominated the seas.

The government also needed oil to make gunpowder for weapons, so a lot of cheap fat didn’t make it to the public. Everyone was so desperate that the British government had to urge people not to cook with paraffin. The usual butter on the shelves was replaced by National Margarine, which most people didn’t like.

Fat and oil were essential in many recipes, though, so the public started saving fat wherever they could. Any fat released from a joint of meat during cooking was usually kept in a jar. This was called “dripping,” and it was the primary cooking fat for several years.[5]

American sausage meat took a while to catch on in wartime Britain, but people quickly noticed that the tins came with a thick layer of fat in them. Far from being put off, they treasured this fat and stored it for use in other recipes. Tinned meat became very popular as a result.

10 Creative Ways We’ve Gotten Through Wartime Rationing

5 Eggless Mayonnaise

Mayonnaise is the most popular condiment in the U.S., appearing on tables more than any other sauce—including tomato ketchup. It is the savior of bland cheese sandwiches and green salads as well as the base for more exciting sauces, like tartar sauce.

In the 1940s, mayonnaise was just as popular as it is today. So, when people ran out of eggs, it’s no wonder that they simply made mayonnaise without.

But what could replicate the strong flavor and silky texture that makes us love mayo so much?

Well, the potato was the best they had. And while it certainly didn’t taste the same, it could still make a smooth sauce with a couple of additions. Oil and fat were needed. Some people used vegetable oil if they could get it, but National Margarine (the replacement for butter) was their only option much of the time.[6]

Once they had the smooth potato, some strong flavors like vinegar and mustard could turn a bland sauce into something that would work—as long as they didn’t expect it to taste like mayonnaise.

4 Carrots

Carrots received a lot of attention from the British government during the war. At the time, it was common knowledge in both Britain and Germany that carrots were good for your eye health.

When the British government started fitting some of its planes with a brand-new AI targeting system, they covered it up by saying that their pilots were eating enough carrots to improve their night vision. (The AI was used mostly at night.) This was to throw off German intelligence and keep the British AI a secret. But it also filtered down to the British public, which duly began eating and growing tons of carrots.

The government turned this new love of the carrot to their advantage, drafting a Disney animator to design a whole family of cartoon carrots to put on leaflets. The public was encouraged to grow carrots and use them in government-provided recipes, including carrot cake, carrot cookies, carrot pudding, and carrot marmalade.[7]

Naturally, some of these recipes worked better than others—most people learned to avoid the terrible ones—but the strategy worked. As carrots are a naturally sweet vegetable, they were a fine way to increase the sweetness of a pudding without having to dip into the extremely precious sugar ration. Carrot cake survived the war, remaining a popular British dessert to this day.

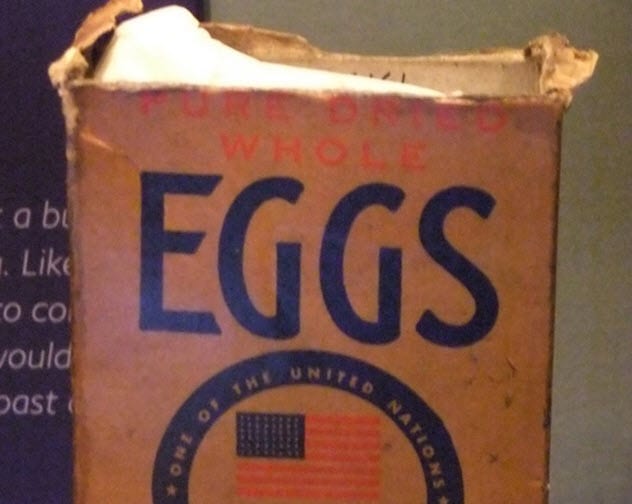

3 Powdered Egg

Chickens were difficult to keep during wartime, so the average Brit was only allowed a single egg a week as part of his ration. (Vegetarians received more eggs, but they got no meat allowance.) People were encouraged to raise their own chickens. If they did, their egg rations were replaced by chicken feed, and they could have their chickens’ eggs free of ration restrictions.

Of course, not everyone had space or time to start a small chicken farm. For those individuals, the powdered egg was brought in from America. This was just a dehydrated egg, which was much easier and cheaper to transport.[8]

The downside?

The public hated it. An energetic government campaign tried to convince people that dried egg powder was really just as good as a normal egg after water was added, but people couldn’t get used to the strange texture.

This powdered egg was put to use in cakes, custards, and omelets. But for years, the traditional fried-egg-on-toast snack was nothing but a dream for many Brits.

2 Kraft Mac & Cheese

Kraft Mac & Cheese (aka Kraft Dinner) is a staple of the North American diet today. Whether that’s a good thing or not is your own opinion. But back in the 1940s, it was an important food for the average American or Canadian family struggling through the years of food rationing.

Despite its wartime success, Kraft Dinner was actually made to help the public during the Great Depression when people needed high-calorie foods for as little money as possible. It first hit the shelves in 1937, though its creators could not have foreseen how popular their product would be during the coming war.

In a time when most foodstuffs were hard to come by, a single ration stamp could get you two boxes of Kraft Dinner. Along with the product’s long shelf life, this made it invaluable and very popular. An estimated 50 million boxes were sold over the course of the war, launching Kraft to the top of the American food chain. So much of the stuff is eaten in Canada today that it has been labeled as Canada’s unofficial “national dish.”[9]

Traditionally made mac and cheese disappeared from American plates almost entirely. Even today, homemade mac and cheese is a much rarer dinner in the United States compared to Europe, which is a testament to Kraft’s dubious legacy.

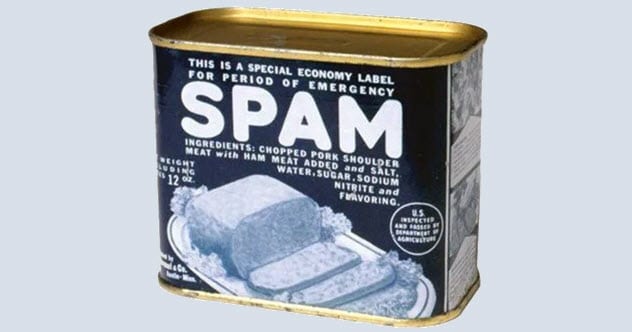

1 Spam

It was a British tradition that the main meal of the day contained “one meat and two veg.” The wartime population tried to follow this as closely as possible, but meat quickly became hard to find.

Under pressure, the British government started importing other meats from across the world with varying degrees of success. Some, like corned beef, were barely tolerated. Others, like the snoek (a species of snake mackerel from South Africa), were shunned entirely because they were just too different for the British palate. But one of the meat products, a canned ham from the U.S. called Spam, proved to be very popular.

Spam certainly wasn’t as good as fresh meat, but it was filling and tasty (by substitution standards). It was also popular with the U.S. Army, which relied on Spam for its long shelf life. While it’s not as popular today, Spam was a staple in both countries for decades after the war. Billions of cans were sold in the 20th century.[10]

Top 10 Weird Experiments And Facts About Dairy