Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

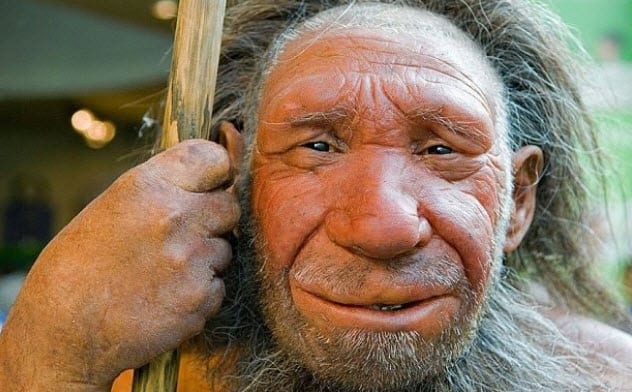

Top 10 Amazing Recent Revelations About Neanderthals

Neanderthals are our nearest extinct family. This link keeps Neanderthals a hot research topic. Fresh finds include the dangers they faced, skills that helped them to survive for millennia, why they looked so different, and how Neanderthals possibly saved humans from extinction.

There remains a lot that researchers want to know. This desire has spawned experiments with living tissue that revived Neanderthals in a truly weird way.

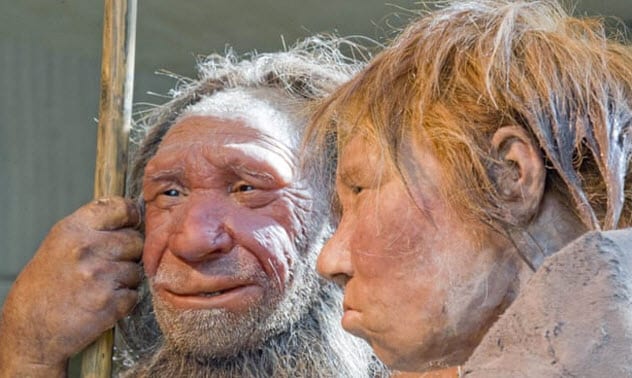

10 Mysterious Faces

From the first moment that researchers became aware of the extinct hominids, the question was asked: Why do Neanderthal faces look so different? Compared to modern humans, their protruding faces had distinctively high cheeks and big noses.

One prominent theory suggested that the features gave Neanderthals a stronger bite. Past evidence of dental damage showed that they used their jaws like a third hand to hold on to something, perhaps while making weapons or garments.

However, a 2018 look at human and Neanderthal skulls blew that theory out of the water. Modern humans turned out to have the stronger bite and yet owned finer features.

As it turns out, the differences may have something to do with physical needs. Neanderthals had more powerful bodies that used more energy, up to 4,480 calories daily. They traveled a lot and sometimes lived in cold environments.

The study found that Neanderthal facial features accommodated nasal passages 29 percent larger than those of humans. This allowed a vastly better intake of oxygen and warm air, both of which could have helped to sustain the highly active hominids during winter.[1]

9 Human-Neanderthal Split Mystery

The human family tree is stunningly complex. Despite all the fossils and DNA technology, scientists still do not know the full evolution story of hominids. One tough nut to crack is the unknown common ancestor to modern humans and Neanderthals. Besides this, it remains unclear when they split into different species.

The fossil record indicates that modern humans evolved 300,000 years ago, but the oldest Neanderthal evidence is tricky. The most ancient remains date back 400,000 years, while some genetic studies found traces of a split from humans as far back as 650,000 years.[2]

In 2018, researchers viewed fossil teeth that surfaced in two places on the Italian Peninsula. Before the detailed examination, the hominid species they belonged to was a mystery. However, the study found distinctive features of the Neanderthal lineage.

Both teeth were also 450,000 years old. This backed up DNA findings suggesting that the split happened over half-a-million years ago. The exact era when humans and Neanderthals forked apart remains unknown, but this closes the gap a little.

8 The Neanderthal Boy

In 2010, a seven-year-old Neanderthal boy was found among a group of 12 related adults and children in El Sidron Cave in Spain. They died 49,000 years ago.

A recent look at the boy revealed interesting things. For example, there was no difference between his growth rate and that of a modern seven-year-old. This likeness could be among the reasons why the two species interbred so easily. While it is already known that Neanderthals had the bigger brains, the boy’s was still developing. It was 87.5 percent of the adult volume. Today, a child of the same age averages around 95 percent.

Neanderthal children matured slower, which suggested that they received a longer care and learning period with adults. It remains unclear if this was a biological advantage.

Another difference was found in the boy’s vertebrae. They were not all fused. Those of modern humans fuse around 4–6 years of age. There was no disease in the young fossil, which suggested that late fusion was normal for a Neanderthal child.[3]

The family group at El Sidron Cave is priceless. As they represent different life stages and generations, they hold the key to finally understanding the complete physical development of Neanderthals.

7 Tailors’ Hands

Despite a slew of discoveries showing that Neanderthals were not brutish cavemen, the rough and clumsy image persists. In 2018, another study added to the more delicate side of these hominids. It was not something that most people would expect. Neanderthals used their hands like tailors and painters, with a precise command on the way they gripped something.

Scientists scanned the hands of construction workers, artists, and even butchers. Then the researchers took note of how entheses manifested (bone scars showing long-term muscle use).

For comparison, 12 prehistoric hands were also scanned and analyzed. The ancient group was equally divided between humans and Neanderthals who lived around 40,000 years ago.

Only half of the prehistoric humans showed the entheses on the thumb and index finger indicative of delicate work. The rest showed the hard labor, brute-force grip entheses on the thumb and pinky. All the Neanderthals showed the hand scars for fine-movement work instead.[4]

6 Neanderthal Health Care

An often overlooked factor in the Neanderthal story is their medical skills. These hominids existed for thousands of years, but in small bands where every individual was likely viewed as valuable to the group. Neanderthals could not have survived for as long as they did without developing their own health-care practices.

In 2018, the remains of more than 30 Neanderthals were picked for a special reason. They all survived some kind of physical trouble. Minor to serious injuries, including broken bones, were all there. More importantly, each individual had recovered from different traumas over the course of his or her life. None were fatal (or there would have been no healing).

This was the first solid proof that Neanderthals had an advanced medical system in place. Not just as a cultural thing, either, but as a major survival strategy. Since they cared for patients and focused on survival, researchers believe that the Neanderthal healers included skilled midwives.[5]

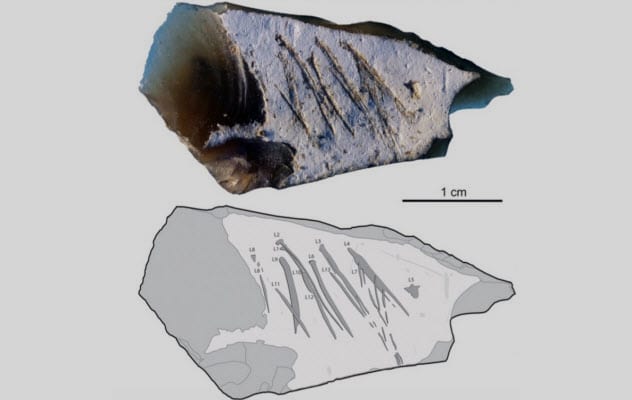

5 Strange Stone Message

The Kiik-Koba cave in Crimea is no stranger to Neanderthal discoveries. Decades ago, excited researchers found an adult Neanderthal and baby inside. During 2018, a flint flake from the site revealed 13 surface marks during analysis. The artifact was around 35,000 years old, and the lines were anything but random or accidental.

Instead, a Neanderthal with acute hand-eye coordination used several pointed stone tools to create the zigzags. This kind of endeavor also demanded great mental focus. The small flint was not made from local stone, raising the possibility that it was brought from another location—perhaps bearing a message.

Scientists agreed that the markings were too labor-intensive to be doodles from a bored Neanderthal. They also discounted the chance that the marks indicated ownership of the tool because other flint flakes were found without any carvings. It could have been numerical information. But honestly, nobody knows what was communicated and whether the small size meant the intended audience was not big, either.[6]

4 Flu-Fighting Genes

A rather scary 2018 study from Stanford University suggested that modern humans once risked extinction because of the flu. The thing that saved them? Mating with Neanderthals.

It is old news that most Europeans alive today walk around with about 2 percent of Neanderthal DNA. During the Stanford study, researchers looked at 4,500 human genes that interact with viruses. Surprisingly, 152 were inherited from Neanderthals and defend against hepatitis C and modern-day influenza A.

When humans first arrived in Europe, Neanderthals had already lived in the region for millennia. Their genetic code was already well adapted to fighting infectious European diseases. Not so for the new immigrants coming out of Africa.

If the two groups had never met, humans would have had to naturally evolve their own resistance. However, flu could have wiped them out before then. Luckily, trysts with Neanderthals produced offspring with ready-made genetic defenses which spread through the human population faster than natural evolution ever could.[7]

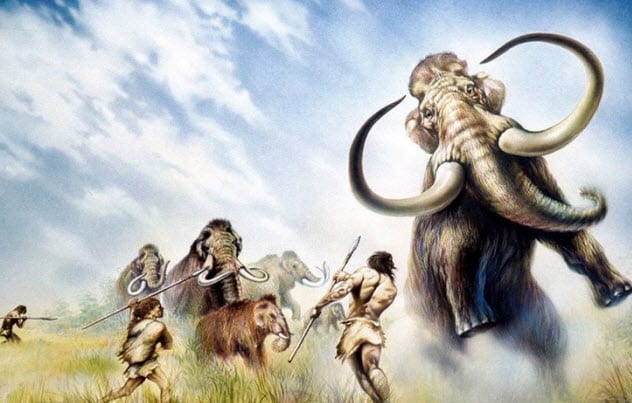

3 They Hunted In Packs

Around 120,000 years ago, two fallow deer died and their remains were discovered respectively in 1988 and 1997. Recovered at Neumark-Nord in Germany, the bones revealed something remarkable about Neanderthals.

In 2018, researchers analyzed the skeletons and found that both were healthy, young male deer. In other words, prime dinner for a hungry caveman. The bones had marks consistent with Neanderthal spears, suggesting that the animals were killed by a skilled group of hunters. If proven beyond a doubt, this is another nail in the “stupid cavemen” take on Neanderthals.

Scientists handed replicas of the spears to volunteers schooled in this line of weaponry. They “hunted” real deer skeletons wrapped in ballistics gel to simulate soft tissue. The bone damage matched that found on the ancient deer. Sensors attached to the spears measured velocity and showed that Neanderthals used close-range thrusts to kill rather than throwing from a safe distance.[8]

A mystery remains. One deer had unexpectedly few butchering marks while the other had none. It was almost as if little to no meat was harvested. For a people dependent on hunting and gathering, this was curious behavior indeed.

2 Child Consumed By Bird

In Poland, Ciemna Cave has a decades-old history of yielding ancient finds. But in 2018, a unique story unfolded. A skeleton’s condition can reveal parts about a person’s life and death. In this case, the tale was gruesome.

Around 115,000 years ago, a Neanderthal child died at 5–7 years old. It remains unclear how the youngster perished, but he or she might have been killed by a massive predatory bird. Back in prehistoric times, this was a real danger.

This suggestion hinged on the fact that the kid was indeed eaten by such a bird. The child’s finger bones showed the trademark damage from having passed through the creature’s digestive tract. It is also possible that something else caused the child’s death and the body was scavenged by the predator involved.[9]

Apart from being the only Ice Age case of a Neanderthal becoming a bird’s lunch, the bones are also the most ancient human remains unearthed in Poland.

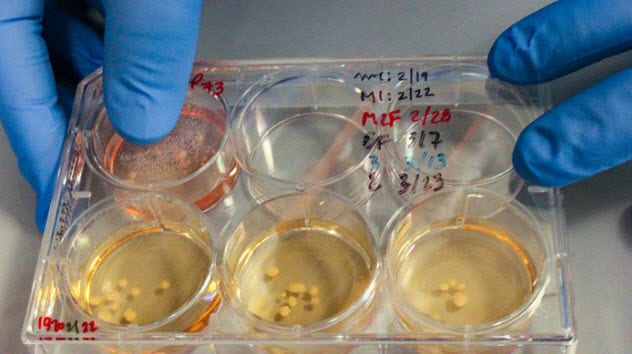

1 Living Neanderthal Brains

The most bizarre development in the field of Neanderthal studies came from a California laboratory. In 2018, during a bid to understand why Neanderthals went extinct and humans thrived, scientists focused on neurological clues. For a more direct look, they decided to whip up some cavemen’s brains.

The full Neanderthal genome is already known. It merely took a few genetic tweaks to turn human stem cells into brain cells matching those of the extinct hominid. The next step was to grow an organoid (smaller version of an organ).

It took 6–8 months for the mini brains to mature at about 0.5 centimeters (0.2 in). The most immediate difference was their shape. Human brain organoids are round, but the Neanderthal version developed an unusual popcorn look. The neural network and paths were also less sophisticated than those of humans.

This does not necessarily imply they were dumber. The study’s achievements are impressive but need more work before blaming brain difference for the Neanderthals’ extinction.[10]

A weird future hope is creating a robot with Neanderthal brains. The idea is to enable organoids to learn through feedback, which will eventually allow them to direct their robot.

Read more fascinating facts about Neanderthals on Top 10 Fascinating Facts About Neanderthals and Top 10 Remarkable Traits Neanderthals Have In Common With Modern Humans.