Technology

Technology  Technology

Technology  Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Icelandic Culture Makes Other Countries Look Boring

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Common Misconceptions About the Victorian Era

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Strange Unexplained Mysteries of 2025

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of History’s Most Bell-Ringing Finishing Moves

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Icelandic Culture Makes Other Countries Look Boring

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Common Misconceptions About the Victorian Era

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Strange Unexplained Mysteries of 2025

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of History’s Most Bell-Ringing Finishing Moves

10 Harrowing Tales From Survivors Of World War I

In 2014, humanity celebrates the centenary of World War I. With nearly 40 million casualties, nine million of them deaths, an entire generation was almost wiped out. One hundred years have passed since Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, since Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and since the lights began to go out all over Europe. It is a milestone, and one we cannot be proud of.

There are things to be proud of, however, and first among them is the bravery and willpower of the men and women who served in the conflict. During one of the most harrowing periods in history, a generation of heroes emerged.

10The ANZACs At Gallipoli

On April 25, 1915, the Allies began the Gallipoli landings—the start of a campaign that would go down in history as one of the most disastrous operations ever undertaken. Over the next eight months, there would be nearly 500,000 casualties, both Allied and Ottoman, with a disproportionate number coming from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps.

Jack Hazlitt was among the Australian troops who were part of the ill-fated campaign. Having lied about his age in order to enlist, Hazlitt became a message runner, crossing the trenches in full view of enemy snipers. “Diggers,” as the soldiers at Gallipoli were known, came to embody a sense of national pride and camaraderie—men “for whom freedom, comradeship, tolerance, and innate worth count for more than all the kingdoms of the world.” Hazlitt’s job as a runner was one of the most harrowing ones. The average life expectancy of a runner at Gallipoli was 24 hours. Hazlitt survived for five months. He died in 1993 at the age of 96.

Corporal Rex Boyden was a Sydney native ordered to participate in an assault on Hill 60. He and his unit had only covered around 250 yards of ground when the order to fall back was given. Suddenly, Boyden felt a thud on the left side of his stomach and crumpled to the ground, leaving him stuck between the Allies and the Turks. As Boyden later recalled: “Any minute I expected the Turks to rush over me in a counter charge on our men, but fortunately they were not game enough. Well I lay there from Sunday morning about 7 o’clock until about 5 o’clock Tuesday morning.” Shooting from both sides continued, but Boyden was protected from stray bullets by the corpses that surrounded him. On Tuesday, his mates finally got to him, and he was able to recover.

One of the most legendary stories of ANZAC bravery earned Albert Jacka, from Wedderburn, Australia, a Victoria Cross. On May 19, 1915, Jacka’s mates provided covering fire on Turkish positions as he ran behind enemy lines, dropped in on the Turks, and attacked. Jacka shot five of the enemy, bayonetted two others, and forced the rest to flee. After the great disaster at Gallipoli, he was sent to France, where he took part in another memorable engagement at the Somme. When his unit was overwhelmed and forced to surrender, Jacka ran up to save his comrades. He fought hand-to-hand against the Germans and was wounded three times, including in the neck. Inspired by his bold act, the Australians turned on their captors and retook the line. He became a legend in Australia, earning the nickname “Hard Jacka,” and his battalion became known as “Jacka’s Mob.”

9The Man With The Dragon Tattoo

There are many stories, from both World Wars, of British and American prisoners successfully escaping captivity. However, tales of Germans who did the same are few and far between. One such man, Oberleutnant Gunther Pluschow, had a harrowing story of escape and survival that would have made his Allied counterparts proud.

Pluschow was a reconnaissance aviator stationed in Tsingtao, China (then a German colony) when World War I erupted. He was known as “Dragon Master” for the dragon tattoo he had on his arm. On November 6, 1914, as Japan declared war on Germany and the conditions in Tsingtao became perilous, Pluschow boarded his plane and escaped the city. He flew 200 kilometers (124 mi) southwest, before being forced to land in Haizhou since his plane was out of fuel. From there, he traveled by boat to Nanking and eventually made it to Shanghai, where he obtained a fake passport and boarded a ship bound for San Francisco.

In California, Pluschow obtained another fake passport that allowed him to travel across neutral America, boarding a steamer in New York and sailing to Gibraltar. It was there that Pluschow was finally apprehended by the British. He was sent to England and interned in the POW camp at Donington Hall.

Two months later, the “Dragon Master” and an accomplice climbed over the barbed-wire fences and made their way to London. The accomplice was later caught, but Pluschow was smarter and disguised himself as a dockworker until he caught wind of a neutral Dutch ship moored in Essex. After an abortive attempt to swim across the Thames, he was able to stow away in a lifeboat.

When Pluschow finally made it back to Germany, he was heralded as a hero—the only German soldier, in either World War, to successfully escape from British soil.

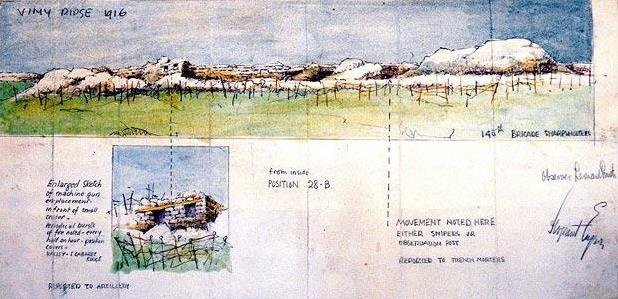

8Leonard Smith Sketched Behind Enemy Lines

It’s hard enough to concentrate with some minor distraction in the background, much less the imminent possibility of death. But that was the exact challenge Leonard Smith had to endure each time he went “over the top.” Smith, a sapper with the Royal Engineers, brought along his tools—a crumpled piece of paper, a pencil, and crayons.

Smith’s job was to scout behind enemy lines and sketch the surrounding landscape, including fixed positions, barbed-wire defenses, trenches, troop formations, and enemy headquarters. Smith even produced a drawing of a tree so accurate that the Allies were able to replace it with a hollow fake version to be used as a listening post.

While Smith was sketching, he had to avoid mortar shells, sniper fire, machine guns—anything and everything that killed millions on the Western Front. Some of his illustrations can be found here.

7Frank Savicki

Frank Savicki and his family were originally from Poland before emigrating to the United States. Just months after he became a full-fledged US citizen, Savicki enlisted in the American Expeditionary Force. He was later captured in the town of Chateau Thierry and led to a prison camp in Laon, France. For the first two days, he was locked in a farmhouse without food or water. After that, he was herded into the prison barracks along with other Allied POWs. For several weeks, Savicki and the other prisoners endured terrible living conditions—everyone slept on the floor without blankets, the water was cold and there was no means of taking a bath, and they were covered in lice due to being unable to wash their own clothes.

Savicki was eventually transferred to another camp in Rastatt, Germany, where he received rations from the Red Cross. Nonetheless, he decided to make a break for it. One night, Savicki tricked the soldier on patrol and locked him in the guardhouse. Savicki bolted from the camp, through hills, forests, and valleys. He finally reached his destination at the Swiss border. Only the Rhine and a German outpost stood between him and safety.

Savicki found a long wooden pole and crawled under barbed wire for hours until he reached the river’s edge, making sure the guards couldn’t spot him. Once he was in place, he gripped the stick tightly, and then pole-vaulted his way to Switzerland and freedom.

6Robert Phillips

When Robert Phillips, a Welsh miner, signed up to fight against the Central Powers, he couldn’t have imagined the ordeals he would face just to get home. Phillips was part of the brutal fighting at Ypres, where he became caught in a poison gas attack. Thousands of men lost their lives, and Phillips barely survived by holding a wet handkerchief to his face. He would later be captured in fighting around Vermelles, Belgium.

For 15 months he was held captive in Germany, where he witnessed his fellow prisoners being viciously beaten by the guards. Phillips knew he had to plan his escape, studying the German routine and shifts until he could elude a patrol and make it to a nearby forest.

Phillips, now hunted as an escapee, stayed away from the roads, raided farms for food, and hid in holes he dug for himself. His 322-kilometer (200 mi) journey eventually led him to the Dutch border. There was just one last obstacle—a German guard on patrol. Phillips crawled within yards of the enemy until he made it over the border to neutral Holland. From there, he returned to Britain—in rags, but a free man.

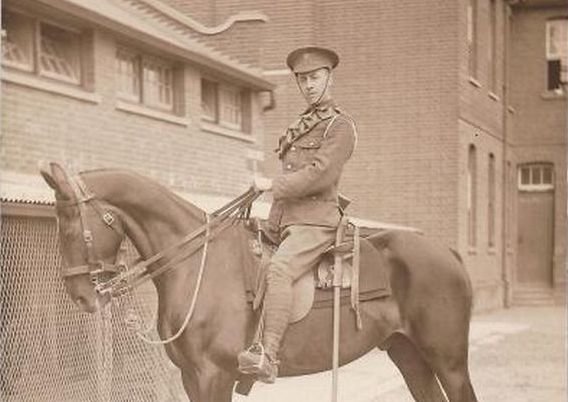

5Cady Hoyte

Volunteers from the English town of Nuneaton are compiling a list of around 300 locals who died during the Great War. At least two of those brave souls perished at sea en route to England. Having already served their country in the deserts of Palestine, the men aboard the Leasowe Castle became victims of a torpedo attack. One survivor, also from Nuneaton, was Cady Hoyte, a soldier in the Machine Gun Corps of the Warwickshire Yeomanry.

In his diary, Hoyte describes being “awakened by a great explosion.” When he came up on deck he was told there were “no more lifeboats or rafts, so you had better jump overboard and trust to being picked up later.” Hoyte desperately swam from the sinking vessel and was eventually rescued, although he noted that two of his hometown friends were among those missing and presumed dead.

Hoyte’s ordeals were not yet over. He was sent to the Western Front where he “faced attacks of poisonous gas, cannon fire, and aeroplane bombs for days on end, standing knee-deep in water and mud.” Thankfully, Hoyte would survive the war. A lover of horses, Hoyte mentioned in his diary how parting with the majestic and intelligent animals grieved him. The book Farewell to Horses: Diary of a British Tommy is based on his exploits.

4The Survivors Of The Titanic

The sinking of the RMS Lusitania by a German U-boat on May 7, 1915 was one of the key moments that brought the neutral United States closer to war. Around 1,200 people lost their lives that day, including 128 Americans. Among those who survived were Frank Toner (fireman) and Albert Charles Dunn (intermediate sixth engineer). How did the pair manage to keep calm in the face of peril? Well, not only had they both survived the famous sinking of the Titanic in 1912, they had also survived the sinking of the Empress of Ireland in 1914.

Perhaps even more worthy of the title “unsinkable” is John Priest. He was among those who escaped death when the Titanic sunk, as were a lookout named Archie Jewell and a stewardess named Violet Jessop. Years later, in February 1916, Priest was on board the merchant vessel Alcantara when it was sunk by a German raider. He suffered shrapnel wounds, but went back to work—this time aboard the HMHS Britannic. There his fate would once again intertwine with Jewell and Jessop.

Serving as a hospital ship, the Britannic was torn apart by a mine off Kea Island in Greece on November 21, 1916. Though the loss of life was minimal, it was nonetheless a harrowing moment for all three. Archie Jewell was pulled into the propeller blades and barely managed to survive. Violet Jessop dove underneath the propeller, but struck her head on the keel, though she was fortunately rescued.

Despite the disasters they had experienced, John Priest and Archie Jewell were still determined to serve their country. The pair were on board the ship Donegal when it was torpedoed off the English coast on April 17, 1917. Jewell tragically lost his life along with 39 other men. However, Priest miraculously survived once more, though his injuries prevented him from rejoining the war effort.

3Wenham Wykeman-Musgrave’s “Thrilling Experience”

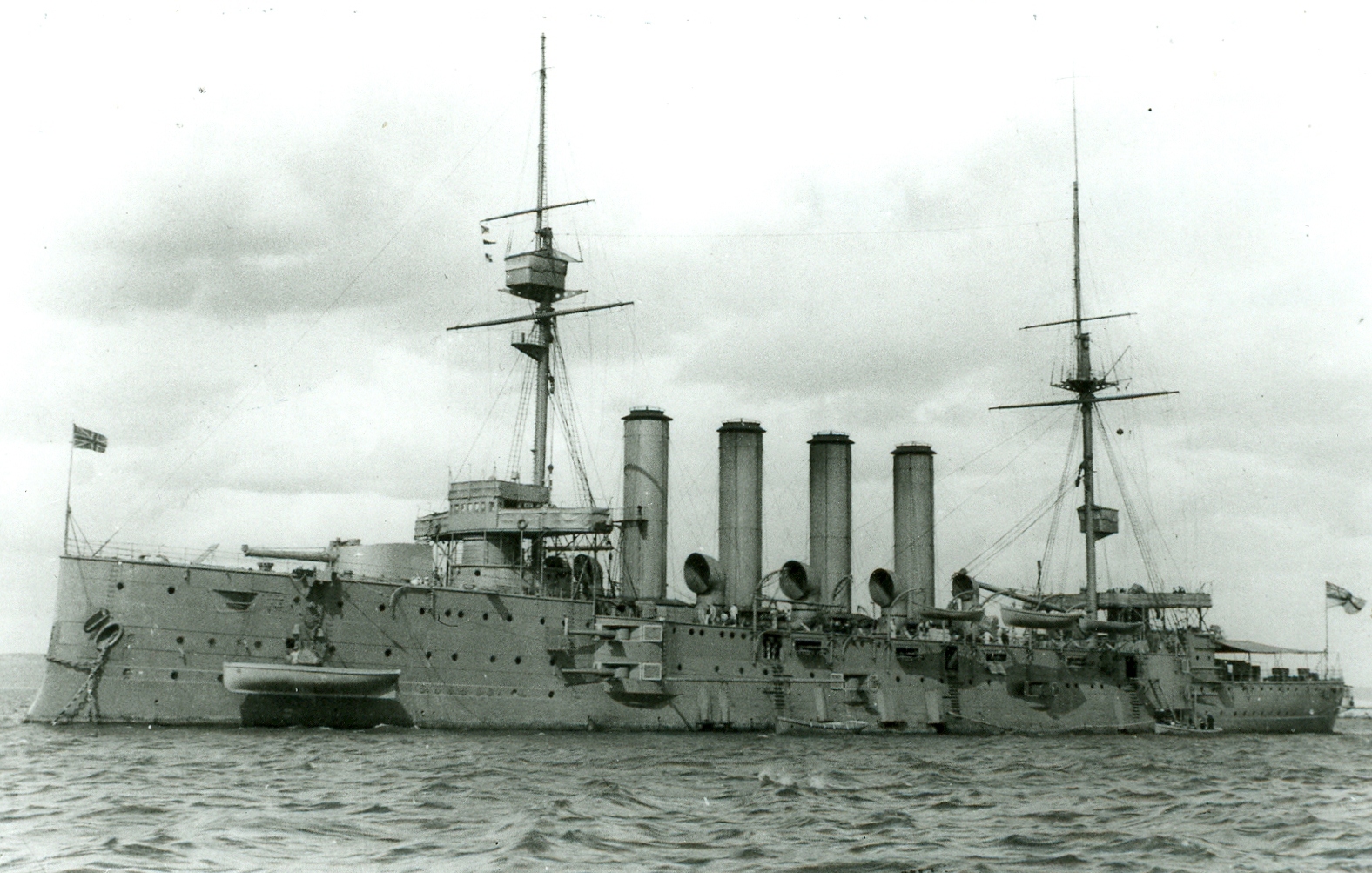

On September 22, 1914, the sister ships HMS Aboukir, HMS Hogue, and HMS Cressy were patrolling off the Dutch coast, tasked with supporting the naval blockade against Germany.

Fifteen-year-old Wenham Wykeman-Musgrave was a midshipman on the Aboukir when it was rocked by an explosion and began to sink. The crew quickly worked to throw anything buoyant overboard to act as flotation devices and Wykeman-Musgrave eventually dove into the water and swam toward the Hogue, which was attempting to pick up survivors. Just as he was climbing aboard the Hogue, the ship was also hit by a torpedo.

The terrified midshipman dove into the water yet again, and made it to the Cressy, which was now picking up survivors from both of her sisters. As he sipped a mug of hot cocoa, Wykeman-Musgrave must have thanked his lucky stars, thinking that the ordeal was finally over. Then, yet another torpedo blasted the Cressy.

All three torpedoes had been fired by the German submarine U-9, which sank three cruisers in less than an hour—1,459 men died and around 300 survived. The British press quickly drummed up a story that an entire fleet of German submarines had been responsible.

As for Wykeman-Musgrave, he clung onto a plank and was eventually rescued by a Dutch trawler. Three days later, he wrote a letter to his grandmother which began with the words, “I had the most thrilling experience . . .”

2Rachael Pratt

Rachael Pratt was one of eight Australian nurses who were awarded the Military Medal during World War I. In May 1915, Pratt enlisted with the Australian Army Nursing Service and was eventually sent to the Greek island of Lemnos to care for wounded soldiers—British, ANZAC, and even Turkish. The military hospital had been in a “state of chaos” for some time, especially after the major debacle at Gallipoli. Nurse Pratt and her team were later transferred to Egypt.

By July 1917, Pratt was in France. She had seen enough of the horrors of war to last a lifetime, but the worst was yet to come. On July 4, her station was hit by an aerial attack. The diligent nurse was busy with a patient when shrapnel from one of the bombs found its way to her lung, puncturing it and tearing through her back and shoulder. Despite the near-fatal injury, Pratt calmly composed herself and resumed treating the injured. It was only later, when the adrenaline wore off and the pain and blood loss took its toll, that she finally collapsed. She was immediately evacuated to England.

After her recovery, Pratt returned to service until the war ended. Her injuries were so severe that she faced a lifelong battle with bronchitis, lasting until her death in 1954.

1Escape From Siberia

http://vimeo.com/38759274

We’ve mentioned personal stories of escapes and survival against all odds, although none can come close to the story of Lajos Petho. Petho, a native of Budapest and a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army, was among the millions of soldiers taken prisoner by Tsarist Russia during the war.

The death toll in Russian POW camps was close to 300,000, more than in any other country. Typhoid, dysentery, and malnutrition were rampant, as were inter-ethnic conflicts among the prisoners. While Slavic prisoners were confined closer to Russia’s industrial centers, German and Magyar troops were often sent immediately to the farthest corners of Siberia.

According to the story handed down in his family, Lajos Petho decided he would not perish in the frigid wasteland. In 1915, he escaped from a POW camp near Irkutsk (just north of Mongolia). According to his son and grandson, Petho was able to avoid capture in the Russian wilderness by using the setting sun as a navigational guide. He obtained food and shelter by working for villagers he met along the way. It took Petho three years and a journey of almost 13,000 kilometers (8,000 mi), before he successfully returned to his family in Budapest.

In 2014, Lajos Petho’s grandson, Ludovic, announced plans to retrace his ancestor’s footsteps for a documentary.

Jo may not have a relative who fought during the First World War, but he damn sure honors the veterans who went through such a harrowing moment in history, a tragic chapter that spiraled out of control.

If you have any thoughts feel free to email him at [email protected] or talk to him at the comments section.