Music

Music  Music

Music  History

History 10 Less Than Jolly Events That Occurred on December 25

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Funny Ways That Researchers Overthink Christmas

Politics

Politics 10 Political Scandals That Sent Crowds Into the Streets

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Facts About The Doge Meme

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Your Christmas Tree Is More Lit Than You Think

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Coolest Stars to Set Sail on The Love Boat

History

History 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the American National Anthem

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Music

Music 10 Surprising Origin Stories of Your Favorite Holiday Songs

History

History 10 Less Than Jolly Events That Occurred on December 25

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Funny Ways That Researchers Overthink Christmas

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Politics

Politics 10 Political Scandals That Sent Crowds Into the Streets

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Facts About The Doge Meme

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Your Christmas Tree Is More Lit Than You Think

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Coolest Stars to Set Sail on The Love Boat

History

History 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the American National Anthem

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

10 Interesting Attempts To Communicate With Aliens

For hundreds—if not thousands—of years, people have had a fascination with trying to make contact with extra terrestrials. So far, all the messages we’ve sent into the universe have gone unanswered—and judging by the confusing, random, and downright weird transmissions you’ll find in this list, it might be a good thing if our communications continue to go unnoticed. If any intelligent life does intercept these varied signals, it’s difficult to know what kind of impression they’ll have of humanity—but it’s a fair bet they’ll think we’re pretty strange.

While people often associate crop circles with communication from aliens, some of the earliest forms of crop circles were actually made by people trying to contact extraterrestrials. For instance, in the 1820s, German mathematician Carl Friedrich concluded that the best way to converse with aliens would be to make a message they could see from above. Naturally, he ventured into the Siberian forest and systematically cut down trees to make a massive triangular shape, and inside the triangle he planted wheat. He also transmitted multiple “sky telegraphs,” which involved using a heliotrope (his own invention) to reflect sunlight towards other planets.

Two decades later, astronomer Joseph Von Littrow, who thought the moon was inhabited, came up with the idea of digging huge symbol-shaped trenches in the Sahara Desert, filling them with oil, and lighting them on fire at night. He hoped that the bright flames would alert space beings of our presence on Earth. Both Littrow and Friedrich assumed that geometric shapes were the ideal way to connect with an alien, since it’s believed that mathematical principles are consistent throughout the universe.

After seeing pinpoints of light on Mars and Venus (probably meteorological phenomena), French inventor Charles Cros came to believe he had witnessed lights from distant, other worldly cities. So in 1869, he took Carl Friedrich’s ideas a step further by using parabolic mirrors to direct light from electric lamps towards other planets. Using something like Morse code, Cros flashed his lights on and off in an intentional pattern which he hoped would be recognized by another intelligent being.

He was doubtful that the small mirrors would be effective, but said that if they did happen to work, “It will be a moment of joy and pride. The eternal isolation of the spheres is vanquished.”

Not unexpectedly, Cros didn’t hear back from the Martians. Despite this setback, he repeatedly petitioned the French government to build a massive mirror capable of burning giant shapes into the deserts of Mars and Venus. For more than one reason (mainly because it was impossible, and also because starting a fire on another planet probably isn’t the best way to say “hello”), the French government didn’t honor Cros’ request, and he was never able to fulfill his dream of alien contact.

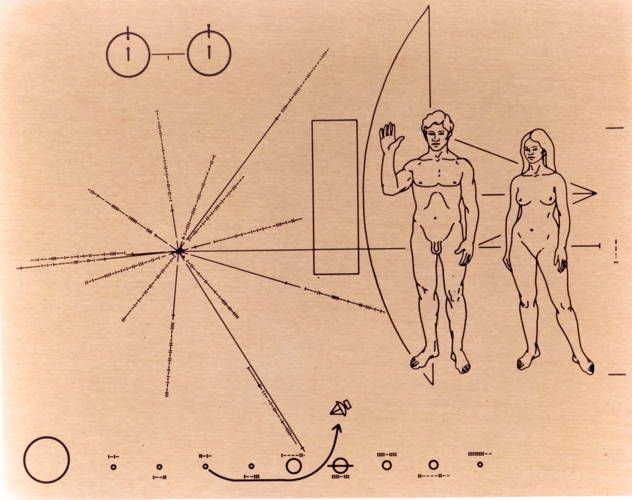

In the early 1970s, NASA launched two space probes, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, with the mission of exploring the large gas planets, the asteroid belt, and the outer reaches of the solar system. In addition to outfitting the spacecrafts with an array of scientific instruments, the astronauts also thought it would be a good idea to tack on a message to extraterrestrials—because after all, you never know.

Famed astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake designed the Pioneer Plaque. The plaque is a six inch by nine inch gold anodized tablet, depicting diagrams of the universe (just in case the aliens need a map), a schematic of hydrogen (the most plentiful element in the universe), as well as pictures of a couple of naked people—once again, why not? Identical copies of the plaque were bolted to the frames of each spacecraft.

NASA lost contact with Pioneer 10 in 2003 and then Pioneer 11 in 2005, and while they both provided loads of insight about our solar system, we’ve yet to answer the big question: can aliens understand our bizarre drawings? Some argue that the symbols are too abstract for an alien intelligence to comprehend, while others worry that we’re giving potentially dangerous life forms a direct map to our planet. Indeed, some also fear that the nude images make humans seem a little pervy. And of course, all of the above groups are outnumbered by those who believe that the whole business is a big waste of time and taxpayer money. Until a little green guy shows up, plaque in hand, thanking us for the directions—we’ll never know.

Around the same time as the Pioneer launches, astronomers were also toying with the idea of using focused, amplified radio waves to connect with unearthly beings. They knew that radio waves were less affected by cosmic dust than light, and they also figured out how to direct radio waves at targeted points many light years into space. For these reasons, it seemed that radio was the best way to reach out into the depths of the universe and deliver a message.

Once again, Frank Drake and Carl Sagan teamed up to concoct another human-to-alien communication. This time their message consisted of seven parts, including an image of a human, the structure of DNA, atomic numbers of common elements, and the numbers one to ten. They transmitted the communication in binary digits, with all the zeroes and ones represented by two different frequencies. Incidentally, the images ended up looking like something out of an Atari game, so if the aliens ever decode the signal they may simply think we’re big fans of 80s video games, and decide to avoid us.

In 1974, astronomers used the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico to direct the message towards star cluster M13, which is home to an abundance of stars and therefore has a better chance of containing intelligent life. The only downside to M13’s location is that it’s 21,000 light years away—so if an alien ever does send a radio reply, it will take us more than forty thousand years to get it.

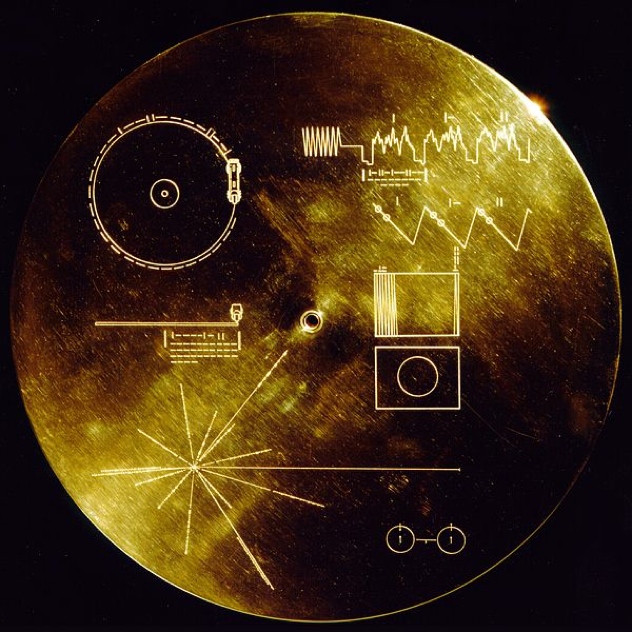

Apparently, scientists in the 1970s were heck-bent on chatting with extraterrestrials, or at least future humans. In 1977, for example, NASA released a third major cosmic-bound message using the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes. Yet again, Carl Sagan and team came up with what they thought aliens would most need to know, and encoded the information onto two, twelve-inch gold-plated gramophone records (one for each space probe). The records contain sounds of nature, various languages, a variety of images, music, and other things meant to sum up life on Earth.

The cover of the records are engraved with many of the same images found on the Pioneer Plaque, except that NASA omitted the nude man and woman since so many people complained about it the first time around. Directions on how to use the record are also included, as well as a needle and cartridge for playback.

Currently Voyager 1 and 2 are at the edge of our solar system, or possibly even beyond it. They’re the farthest man-made objects from Earth. Surprisingly, they are still sending communications back to our planet—sadly, none of these so far have been from aliens.

While some considered the nude couple on the Pioneer Plaque nearly pornographic, others—such as artist Joe Davis—decided that the images weren’t nearly explicit enough. He felt that a hairless man and a woman with no external genitalia were too sanitized, and would give aliens an inaccurate picture of our bodies while telling them absolutely nothing about human reproduction. In 1986, he therefore decided to do his part to remedy the “problem” by creating a space message that was undeniably sexual and uniquely human: it would contain the sounds of vaginal contractions.

Somehow Davis convinced a group of ballet dancers to let him record their vaginal contractions with a special devise he had designed, which included a sensitive pressure transducer. Using MIT’s Millstone Hill Radar, Davis was able to send about twenty minutes of his transmission into space before the US Air Force caught wind of the project and put a stop to it. Nevertheless, the transmission was still longer than Carl Sagan’s Aricebo message, and it has already reached two star systems, Epsilon Eridani and Tau Ceti.

Aleksandr Leonidovich Zaitsev, a Russian radio engineer and astronomer, sent at least five radio-based communications into space, including two Cosmic Calls and the Teen Age Message.

The first Cosmic Call was sent in 1999 as part of the publicly funded Team Encounter program. It contains what those involved in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) call the Rosetta Stone of interstellar communication. This “Rosetta Stone” is a bitmap, which uses symbols to explain everything from basic mathematics to chemical and physical processes on Earth. Let’s just hope that aliens are better at figuring out puzzles than humans, since the pages of seemingly random dots and lines make absolutely no sense to the average person.

Also included in the Call is a bilingual glossary, another copy of the Aricebo message, and—to honor those who helped pay for the project—a collection of images and videos sent in from everyday people. The second Cosmic Call, sent out in 2003, is nearly identical to the first and contains more content from ordinary citizens. Both messages were transmitted from the Evpatoria Planetary Radar in the Ukraine.

In 2001, Zaitsev and his team put out another radio communication with the assistance of teenagers from Moscow, Kaluga, Voronezh, and Zheleznogorsk. For this broadcast, Zaitsev felt it was especially important to relay the uniqueness of the human culture (as opposed to mathematics, which advanced aliens would probably already know), so he enlisted the teens’ help in selecting artwork, music, and even the message’s target destination. The group chose to send the collection to Ursae Majoris, as well as five other stars with solar systems similar to our own. If there are any beings near Ursae Majoris, then in 2047 they’ll be able to listen to Beethoven, Vivaldi, and Gershwin.

In 2008, the research institute EISCAT broadcast a Doritos advertisement into space for six straight hours—amazingly, the planet wasn’t instantly vaporized by upset aliens. Of course, we can’t fault EISCAT too much for blasting the universe with junk-food ads, since it was all part of a clever promotion to secure donations after the space center experienced a major loss in funding.

The radar message was sent as an MPEG coded in 1s and 0s, and directed at a potentially habitable solar system in Ursa Major, a mere forty-two light-years away. The astronomers involved explained that while normal television advertisements also drift into the universe, their signals dissipate to the point that they become drowned out by other space “noise.” The Doritos broadcast, however, was sent with a 500MHz ultra-high frequency radar, and, thankfully, will reach its destination intact.

Since the world didn’t actually end in December 2012, the title of this cosmic time capsule, “The Last Pictures,” is something of a misnomer. Nevertheless, it’s currently traveling through space on a communications satellite, patiently waiting to explain our existence to future earthly inhabitants or anyone else who happens to stumble upon it after the planet meets its demise.

The project was designed by artist and author Trevor Paglen, who undoubtedly figured that he’d take advantage of the end-of-the-world paranoia to garner some publicity for his work. Whatever his motivation, the one hundred photos included on the ultra-archival disc are truly amazing—depicting everything from cave paintings to nuclear explosions. In an effort to accurately convey what life was like on the planet, Paglen spent five years consulting with scientists, anthropologists, artists, and philosophers to get their take on mankind’s most important cultural landmarks.

The Last Pictures are nano-etched on the disc, surrounded by a gold casing, and expected to last billions of years.

While the most publicized attempts at communicating with aliens involve using advanced technology, there are those who say that the only equipment we need is something we all possess—a brain.

Arguably the most famous self-proclaimed E.T. conversationalist is Dr. Steven Greer of the recently released alien documentary “Sirius.” Several times a year, Greer takes groups of people out to remote locations for communal meditation sessions. During these events, participants are said to enter a higher level of consciousness which, in addition to connecting them with aliens, allows them to remember past lives. Greer claims that his “contact expeditions” are always successful, and that his participants are ambassadors for the universe.

Who knows what Greer’s followers are saying on our behalf; let’s just hope they’re only chatting with friendly, peace-loving aliens.

Content and copy writer by day and list writer by night, S.Grant enjoys exploring the bizarre, unusual, and topics that hide in plain sight. Contact S.Grant at [email protected].