History

History  History

History  Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

10 Americanisms That Aren’t All-American

There’s no mistaking the unique identity of America or denying the power of the nation’s global influence. But in a country where the Statue of Liberty was thought up and designed by the French, where trick-or-treating derives from an ancient European custom, and where even the music for the national anthem was composed by an Englishman, it’s also hard to deny that American icons sometimes have some surprisingly non-American origins.

10Cowboys And ‘Dudes’

The cowboy and his blue jeans, boots, and big-buckled belt—not to mention the characteristic hat—are globally recognized as an archetype of American culture. He seems essential to the American West, but he didn’t originate there. The true roots of the cowboy are Hispanic, not American, since the American “cowboy” grew out of the word vaquero.

A vaquero is a guy on horseback who works with cows. The word derives from the Spanish vaca (cow), and it literally means “cowman.” Donald Gilbert Y. Chavez, a historian interested in cowboy origins, has said that cowboy culture can be compared to the development of the motorcar: “If the vaqueros invented the car, the styles change a little bit, but you still have the basic chassis, four wheels, and a motor.”

Many white and African-American cowboys originally learned their skills from Mexican vaqueros who worked across the southern states. Interestingly, the word “dude” also began in this context. Dude, according to Chavez, derives from the Spanish phrase lo dudo, which means “doubtful one.” It refers to an Easterner who is new to ranch work in the West. Understandably, the more experienced vaqueros would refer to these trainees as doubtful—a far cry from the meaning of “dude” today.

9Skyscrapers

Skyscrapers have long been recognized as an American icon. While many see these constructions as symbols of arrogance and hubris, for others they are permanent marvels, ingrained into the psyches of Americans everywhere. The Empire State Building and the World Trade Center in particular have come to be associated globally with the US.

When immigrants were pouring into America by the shipload, the cities swelled, and landowners found that they could easily optimize returns on their purchases by building as high as possible. Apartment blocks sprouted everywhere, although these were nothing new (apartment blocks have existed since Roman times). Proto-skyscrapers were constructed next, but these required thick masonry bases in order to support the weight of the towering walls. This made the lower levels too cramped. Similar constructions with up to 12 stories had already been built in Edinburgh.

Skyscrapers as we know them today were really born along with a technology that revolutionized architectural design—metal columns and frameworks that could support the weight of the upper floors. James Bogardus was the man who pioneered this method in the States. From that point on, the only way was up.

But although the skyscraper is usually hailed as an American invention, the foundation of skyscraper technology is firmly sunk in British history. The Flax Mill in Ditherington, Shrewsbury, is the world’s oldest iron-framed building, which technically makes it the world’s oldest skyscraper. It is frequently referred to as such, despite only being five stories tall. This is because the same metal framework design that gave rise to American skyscrapers was used for its construction in 1797. The Ditherington Flax Mill predates Bogardus’s work by roughly 50 years.

8‘Your Name Is Mud’

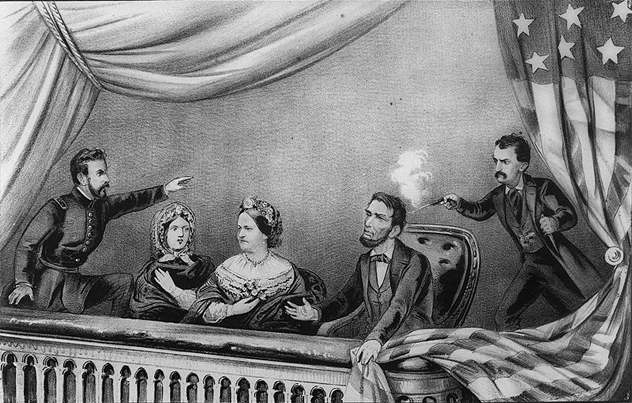

It’s understandable why some Americans think this expression is connected to John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin. In reality, the only thing linking this saying and the bungling, racist Booth is a weird coincidence of history. Booth shot Lincoln in the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre in 1865, but as this previous list shows, Booth’s fate was arguably sealed when he ruined his own dramatic getaway plan. Evading his pursuers by leaping from Lincoln’s private balcony, he caught a spur in the stage curtains, landed awkwardly on the stage, and broke his leg. He managed to flee the crime scene, but needed medical help. The man who treated Booth was Dr. Samuel Mudd.

Lincoln had been well liked and respected by most Americans, and anyone aiding and abetting John Wilkes Booth was immediately deemed a diabolical traitor. Dr. Mudd was no exception. In the hysterical aftermath, Mudd was implicated as a co-conspirator in the assassination plot. His reputation was never fully restored in his own lifetime, even though he was officially pardoned later that same year.

Many Americans now believe that the expression “his name is mud” originates from the wrecked reputation of the infamous Dr. Mudd, but this isn’t true. The expression is recorded in a dictionary of slang published in 1823—over 65 years before anyone had heard of Mudd.

7The Cape Canaveral Countdown

“5–4–3–2–1.” This idea of reversing a countdown, instead of saying, “1–2–3–go” or “ready–steady–go,” apparently comes from a perfect example of life imitating art. Long before any of the American space launches, the “reverse countdown” launch sequence had occurred in a 1929 German sci-fi movie.

The silent sci-fi film in question is Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon). The reverse countdown was used in this film as a way of prolonging the audience’s tension. You can judge for yourself whether the effect succeeds by watching a clip of the countdown sequence. If you’re a physics nerd or you suffer from insomnia, you might try watching the three-hour-long, uncut version with all its technical explanations, occasional attempts at plot, and the odd melodramatic outburst.

Lang collaborated with rocket scientists while making the film. Hitler withdrew Woman in the Moon from the public eye for years, thinking it might give away too many newly discovered secrets of rocket science to rival nations. The Third Reich, while working on their deadly V-1 and V-2 intercontinental missiles, didn’t want to give anyone else any clever ideas. When the German economy derailed after World War II, the reverse countdown became an integral part of the language of the space race from the ’60s onward.

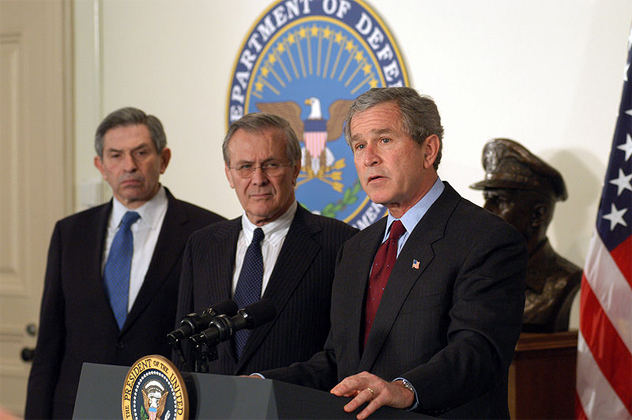

6‘Axis Of Evil’

The controversial term “Axis of Evil” originates from George W. Bush’s State of the Union address in 2002. From there, it moved into common media usage and became a household phrase practically overnight. The term “Axis of Evil” describes an imaginary line connecting individual nations who collectively support global terrorism. However, the roots of the term extend back much further, into pre-war Europe.

The idea of an imaginary axis joining separate nations was first applied in 1930s Hungary. Gyula Gombos, the Hungarian prime minister at the time, referred to an “axis” connecting Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany with his own country. The Fascists then borrowed the term in 1936, saying that the line between Berlin and Rome was not an obstacle, but an axis around which like-minded European nations could turn. “Axis of Nations” came into English use from there, and caught on during World War II as a collective term for Germany, Italy, and Japan—the Axis Powers, as opposed to the Allied Powers.

5‘Die Hard’

This expression became famous with the 1988 movie of the same title. Noted in a previous list, the “die hard” New York cop, John McClane, performs the most improbable feats of gratuitous action-porn in the name of every cherished American ideal. But at the time of the film’s release, the term “die hard” itself had already been in use for well over a century.

A regiment of the British Army earned the nickname “Die Hards” when their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir William Inglis, was wounded at the Battle of Albuera in Spain during the Peninsula War of 1811. While his men fought off a determined attack by the French, Inglis lay bleeding from injuries to his chest and neck. Half dead himself, he refused to leave the battle, and encouraged his soldiers by yelling, “Die hard the 57th, die hard!” Members of the 57th Foot (The West Middlesex) Regiment have been known as the “Die Hards” ever since.

McClane’s catchphrase, “Yipee ki yay,” is, however, all-American. “Yippee” is officially an American word, and “yipee ki yay” most likely evolved from a quaint but catchy Bing Crosby song.

4‘Trophy Wife’ And ‘Bimbo’

The concept of a “trophy wife” comes from Greek and Roman times, when powerful statesmen and warriors claimed the most beautiful women from among their conquered enemies. This practice is mentioned in the Italian poet Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso,” written in 1532. In the late ’80s, American editor Julie Connelly applied this tradition of the ancient world to today’s reality, coining the phrase “trophy wife.” Although the term originally had a complimentary connotation, it eventually came to refer to a woman who was something of a bimbo.

As it turns out, “bimbo” isn’t fully American in its origin, either. It comes from an Italian word meaning “baby” or “child,” and it was used, at first, as a derogatory term for persons of either sex. The word changed its meaning over time, and it eventually came to refer to a woman who has great looks but a low intellect. These days, “bimbo” is of course synonymous with other derogatory phrases like “dumb blonde” or “valley girl.”

3‘My Way’

The song “My Way” is a massive piece of Americana, but it’s not all-American. French musician Jaques Revaux composed the tune for “My Way” with French singer Claude Francois. Originally, the song was called “Comme d’habitude” (“As Usual”), and the original lyrics were about a miserable guy sticking it out in an unhappy relationship. Canadian singer-songwriter Paul Anka heard “Comme d’habitude” while on vacation in France in 1967. He liked the tune so much that he bought the rights. Two years later, when Sinatra told Anka he was retiring, Anka rewrote the lyrics especially for the occasion. “My Way,” as we know it today, was at last complete.

Sinatra recorded “My Way” in 1969. The song was so popular that it spawned several cover versions over the decades that followed. Sinatra didn’t retire but continued singing for the next 25 years. May 13th is now officially Frank Sinatra Day, commemorating his contribution to American culture.

2‘The Only Thing We Have To Fear Is Fear Itself’

This phrase comes from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s inaugural address, but many people doubt that he thought of it himself. Roosevelt may well have gotten the idea from reading Thoreau, who wrote in his diary on September 7, 1851, “Nothing is so much to be feared as fear.” However, it seems the phrase isn’t original to Thoreau either. According to Philip Henry Stanhope in his Notes on Conversations with the Duke of Wellington, the Duke of Wellington is supposed to have said, “The only thing I am afraid of is fear,” during a conversation about cholera in 1831.

Others have argued that an earlier use of the phrase can be found in the writings of the Duke’s fellow Englishman, Sir Francis Bacon. He’s widely acknowledged to have penned the Latin words nil terribile nisi ipse timor (“nothing is terrible except fear itself”) in Division of the Sciences, published in 1623. Bacon may have also preempted another American president when it comes to commonly quoted phrases. The succinct expression “time is money” was first coined by Benjamin Franklin in his “Advice to a Young Tradesman, Written by an Old One,” published in 1748. But, over a century earlier, Bacon wrote, “Time is the measure of business as money is of wares; and business is bought at a dear hand,” in his essay “Of Dispatch.”

1Semper Fi

Nothing quite says America like the buzz-cut devil dogs of the United States Marine Corps. The Marine Corps War Memorial statue, depicting the flag-raisers of Iwo Jima, is probably one of the most renowned American icons of all time, not too far behind the Statue of Liberty, Mount Rushmore, and the Lincoln Memorial. But what about the Corp’s motto, Semper Fi?

Semper Fi is shortened from Semper Fidelis, meaning “always loyal” or “always faithful.” It is a succinct summation of the Marines’ core values, centering on loyalty to the corps, the country, and the mission at hand. The Marines adopted the motto in 1883, but this decision was most likely influenced by longstanding connections with a band of exiled Irish soldiers known as the Irish Brigade.

The Irish Brigade fought in America’s war for independence and has served with the United States Marine Corps since its founding in 1775. For example, a large number of the American Marines who fought in the dramatic sea battle of Flamborough Head in 1779 probably came from the Irish Brigade. But what were they doing there in the first place?

Simply put, these globe-trotting Irishmen had nowhere else to go. The Brigade had been formed in Jacobean times, and its members had sworn allegiance to the deposed King James II and the Catholic faith. As they saw it, James II was the only true king of Britain and Ireland. Rather than betray their faith and king, the Brigade preferred to live abroad and fight for the French army instead. They remained in faithful service to the French until around the time of the French Revolution, when supporting royalty quickly became a bad idea.

After many decades of loyal service, they were awarded their motto, Semper Et Ubique Fidelis (“Always and Everywhere Loyal”). After being officially disbanded, some joined Napoleon’s Irish Legion, while the remainder set off for America. The rest, as they say, is history.

Read more for free: htrwilliams.com.