Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Forgotten Battles That Shaped History

The Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066, is widely regarded as a defining moment in English and European history. The victory of William the Conqueror against the Saxon king Harold Godwinsson was a direct result of the latter’s march to defeat the Vikings at Stamford Bridge just weeks prior.

It’s worth noting, however, that the largely forgotten Battle of Fulford, which occurred just days before Stamford Bridge, was where it all began. When the Vikings landed on England’s shores, the Earls of Mercia and Northumbria decided to meet them in battle instead of awaiting a siege; the results were catastrophic. The armies of Mercia and Northumbria were almost completely destroyed and King Harold had no choice but to force march his army north, eventually defeating the Viking forces. Still, the victory was a hollow one. The losses suffered by the North meant they could not further reinforce Godwinsson’s army.

Thus, the last Saxon king had no choice but to lead his tired, depleted host back south to face the Duke of Normandy at the crossroads of history—his fate, and all of England’s, sealed by the results of a battle long forgotten.

Here are 10 other lesser-known or forgotten battles that have shaped the world as we know it.

10The Turning Point At Kapyong

April 22–25, 1951

When the Battle of Kapyong is mentioned, it elicits a blank stare among Australians. This is no doubt evidence of the fact that not just the battle, but the Korean War in its entirety, has been known as “The Forgotten War.” The seesaw conflict which saw capitals and major cities change hands numerous times is still prevalent in today’s world with the animosity between North and South Korea.

Though the war ended in a draw, it could have led to a much grimmer fate for the region as a whole had it not been for a handful of Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders. This ragtag group of men were tasked with defending a position from an estimated 10,000 Chinese and North Korean soldiers.

From April 22 to 25, the ANZAC forces defended Hill 504 while the Canadians defended the nearby Hill 677. The Canadians of the Princess Patricia’s Infantry fought tooth and nail against the attackers. The 3rd Royal Australian Regiment, meanwhile, in an act of desperation, called on the Kiwis to deliver artillery strikes near friendlies just to wipe out the invading forces.

By morning of the third day, the Chinese and North Koreans had had enough and withdrew. Both aforementioned units received US Presidential Citations. Despite their valor on the field, the Allied troops hardly received public recognition. According to some veterans, they were even turned away from clubs because the battle itself, and the entire conflict, was “not even a proper war.”

The forgotten Battle of Kapyong marked the final major Chinese offensive during the Korean War, saving Seoul. This important milestone has led veterans and historians to call on institutions to educate today’s youth about the event.

9The Forgotten Army At Imphal And Kohima

March–July, 1944

The battles of Imphal (March 8–July 3, 1944) and Kohima (April 4–June 22, 1944) marked the farthest limits of the Japanese advance into India. For weeks, the British had known nothing but defeat in the long march from Malay and Burmese regions all the way to the hinterlands of India.

The entire Chinese-Burma-India Theater had been dubbed “forgotten” during the course of the war, and even the British 14th Army, led by General William Slim, has been called “The Forgotten Army.” Reinforcements, rations, and equipment went to other theaters of operation, most notably the Western Front, while Slim and the men had no choice but to make do with what they had. Diseases such as malaria and dysentery were rampant, but the men held on.

By late May 1944, the situation had become so desperate that the men had to resort to hand-to-hand fighting to conserve ammunition. Then, almost as suddenly as the thunder of mortar fire, the Japanese assault was blunted, leading to a near-immediate collapse. The British and Indian troops rushed head-on to harry the enemy from India’s borders all the way back to the tip of Burma.

While it might have been forgotten during World War II, the battle has now gained renown in British and Japanese historical circles—it’s been named the “Greatest British Battle” by the National Army Museum.

Sadly, the battles of Imphal and Kohima were largely forgotten in India as well. Though thousands of Indian soldiers, including the highly skilled Gurkhas, took part in and perished in the fighting, the entire conflict itself is mired by controversy or indifference. As some historians note, it may take decades to fully embrace the significance of the battles due to the mentality that “Indians were fighting for a colonial power.”

Had they any doubts about how the actions of their fellow Indians and the British affected history, they should look no further than the results of Japanese occupations of China and Manila. By preventing the Japanese from penetrating further into India, the civilian populace was largely spared the tragedies that befell several Asian nations.

8Italy’s Last Stand At Monte Grappa

November 1917

The Battle of Monte Grappa late in 1917 has had little mention in history books, but it was perhaps the most important turning point in World War I for the fortunes of Italy and Austria-Hungary, and likely even the German Empire.

The Battle of Caporetto was a humiliating defeat for the Italians. Forty thousand soldiers were either dead or wounded, 280,000 were captured, and 350,000 more deserted. After the combined German and Austro-Hungarian force obliterated the Italian Second Army, the nation itself realized, quite surprisingly, that they had no mobile reserves left.

It was therefore imperative that the remaining able-bodied men hold their ground at Monte Grappa until the Allies could reinforce them. The very fate of Italy, and likely the entire Allied war effort, hinged on the result of the battle.

This was at a point in time when both the Allies and the Central Powers teetered on the brink of collapse due to economic difficulties, mounting casualties, and war exhaustion. A breakthrough in Italy would have led to its capitulation; combined with the Russians being taken out of the war a month later, it would have become an undeniable boost to the morale of the Central Powers. Likewise, Italy’s surrender would have freed up millions of troops that could be sent west.

But the Italians held the line—from the foot of the mountain to the narrow passes thousands of meters above. The Austro-Hungarian advance was checked. By December, many elite German battalions were reduced to just a fraction of their strength. The troops of the Central Powers, from their vantage point in the mountains, could see Venice just a few kilometers away. They would never reach it.

7A Minor Wound At Poltava

June 27, 1709

Charles XII, ruler of Sweden, proved he was a brilliant tactician at a young age. He also knew that it was in his time that Sweden would have its greatest chance of achieving hegemony in Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe. In 1700, the 17-year-old monarch was given an unlikely advance present—a Russian-led conflict. The Russians saw the young king as weak and inexperienced, and to this end launched an invasion alongside Denmark-Norway, Saxony, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Nine years later, only Russia stood, its former allies crushed and forced to the peace table by the Swedish king. Charles was a highly skilled general, able to see the flow of the battle and react accordingly, prompting Voltaire to call him “The Young Warrior King.” Likewise, Sweden boasted the most modern army in the world at the time. The field of Poltava in modern-day Ukraine would decide the fates of both nations, and that of the region.

Just a few days before the pivotal battle, Charles was shot in the leg while assessing the field. This was no flesh wound, either—it was so serious that he was forced to delegate the task to two of his marshals. Thus, on June 27, 1709, the young Swedish king recuperated in his tent, unable to see first-hand how the battle would slowly unfold. His two marshals, who bore a deep grudge against each other, were unable to coordinate the troops. The Swedes were slaughtered by the Russians under Tsar Peter. The Swedish king took flight, both he and the rest of Europe astounded at the results of the battle. Europe’s most modern and professional army had been defeated by “rabble.”

The Russian tsar would be known in history as Peter the Great; Charles of Sweden, meanwhile, wandered the land to escape the Russians until he eventually died a mysterious death.

The Battle of Poltava marked a major turning point in European history, one whose repercussions are felt to this day. Russia finally came of age; Sweden lost its place as a major power. Though historians believe Sweden had no chance of winning the battle, we should take note that it was not merely about winning, but simply keeping its armies intact. With the near destruction of the army and its king in flight, Sweden had virtually no chance to oppose Russia in the future. And without Sweden as an effective deterrent, no other great power in the region could oppose Russian ambitions.

6The Inca Emperor’s Hubris At Cajamarca

November 16, 1532

We’ve mentioned before how the Incan Civil War between Huascar and his half-brother Atahualpa led to the former’s loss and capture. It is also worth noting that the end of the war between the two brothers significantly raised not just Atahualpa’s morale, but his arrogance as well. Encamped in the north of Peru where the Spaniards would later make their headway, Atahualpa believed these men were not gods but regular people, albeit potential subjects.

Francisco Pizarro, the leader of the expedition, could not count on retreat or reinforcements deep in the Peruvian jungles. He enticed Atahualpa to meet him in the plaza of Cajamarca. So it was that with Atahualpa’s naivete and obstinacy did he lead an estimated 80,000 Incan troops to meet the 168 Spaniards. Despite the sheer, overwhelming numbers, Atahualpa went to the town square with less than 10 percent of his actual forces, all of whom were only armed with a few token, ceremonial weapons. It would be sheer madness for the hopelessly outnumbered Pizarro to attack him.

As the meeting began, the Spanish friar, Vicente de Valverde, offered Atahualpa a Bible, saying, “this is the word of God.” The emperor of the Incas didn’t know what to do with the book, so the friar reached over and opened it for him. This angered Atahualpa (for no one would have dared think of him as a fool), and he threw the Bible to the ground.

Pizarro and the men were quick to react. The measly group of Spaniards, clad in armor and riding warhorses, surprised the Incan troops. Musket and cannon fire and an assortment of European blades mowed down thousands of the Incas within a short span of time. Atahualpa, the emperor who led an army that outnumbered the Spaniards nearly 500 to 1, was taken captive.

The Spaniards thought he would incite a revolt and sentenced him to be burned alive. Atahualpa did not desire such a death, so he accepted baptism, which gave him the opportunity to be killed by strangulation, instead of fire. With Atahualpa gone, the conquistadors crushed the remaining pockets of local resistance in South America, leading to Spanish hegemony for centuries to come.

5A Rival’s End At Flodden Field

September 9, 1513

The year 2013 marked the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Flodden Field, which over the years has gained renown and near-legendary status in Scotland. In other parts of the Empire, however, it’s one of the least well known, which prompted the British government to spend £1 million ($1.65 million) on events to commemorate the occasion.

By the early 1500s, it seemed Scotland was poised to achieve a lasting independence. King James IV of Scotland was a popular, beloved monarch; under his rule, the Scots expected a bright new era of “Perpetual Peace” with England.

That dream was cut short in the fields of Flodden when war inevitably broke out between England and Scotland. Despite outnumbering the English army, the Scots attempted to advance toward the English ranks with 5.5-meter (18 ft) pikes. These weapons were cumbersome, meant for defense; the English weapon, the bill, was shorter and easier to wield. Likewise, arrows and gunfire rained down from the English lines, blunting the Scottish charge.

Estimates of the casualties suffered by the Scots vary from a conservative 5,000 to as high as 20,000. James IV, the beloved Scottish monarch, was also killed in battle, becoming the last British king to have had such a fate. Likewise, dozens of earls, chieftains, knights, religious leaders, and members of parliament also fell. The severe losses in both men and able leaders crushed Scotland’s dream so much so that women had to be banned from weeping in the streets of Edinburgh. The great rivalry neared its end, and within a century the crowns of Scotland and England were united.

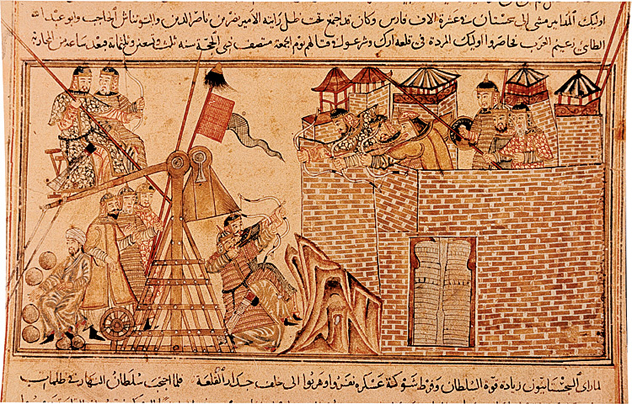

4Halting The Mongols At ‘Ain Jalut

September 3, 1260

The Middle East has had a tumultuous and never-ending history of conflict, often due to religious differences. But the long-standing enmity between the Muslims and Christians in the region was ultimately put to the test against the Mongols, of all people.

The Mongol campaign was led by Hulagu Khan, who had already forced the submission of various dynasties and kingdoms and caused the destruction of Baghdad. Over 300,000 Mongol warriors and their mercenary retinues were poised to strike into Egypt. Hulagu had even sent envoys to Christian nobles in the Levant, who were seriously entertaining the notion of a “Franco-Mongol Alliance.”

Then, almost as if by a miracle, Hulagu’s brother, the Great Khan Mongke, suddenly died, prompting Hulagu to return to the steppes to facilitate the succession. An alliance between the Mongols and Christians never materialized. Nobles felt that Muslims were even more preferable neighbors compared to the barbarian tribes; they even gave the Mamluks safe passage and the right to purchase supplies. The Pope himself declared that anyone who supported the Mongols would be immediately excommunicated.

Thus, the Mamluk sultan Qutuz knew the Mongols would be at a disadvantage. Hulagu Khan left his lieutenant Kitbuqa (or Kitbuga) in command of over 20,000 Mongols and an unknown number of mercenaries. Qutuz, meanwhile, marched through Crusader territory to meet the threat.

On the field of ‘Ain Jalut (the “Spring of Goliath”), the Mamluks under Qutuz forced Kitbuqa to charge their forces recklessly, feigning a retreat. The tactic, so often used by the Mongols to devastating effect, was their downfall. Reserve cavalry forces swung from the sides, hemming the Mongols in a trap. Kitbuqa and most of his forces were slain where they stood.

The Mamluks quickly consolidated their position in the Holy Land. Qutuz would later be assassinated by his comrade, Baybars, who declared himself the new sultan. Meanwhile, far in the east, Hulagu vowed revenge against the Mamluks to no avail as his attention was diverted elsewhere—his Mongol kin had converted to Islam and condemned his wanton cruelty against the Muslims.

3Christianity’s Survival At Constantinople

A.D. 717–718

History has often told us of the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, and the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 where an unlocked door doomed the city. We often forget the battle at its gates hundreds of years before these events that very likely saved Christianity.

In A.D. 704, the deposed Byzantine emperor Justinian II asked for the assistance of Tervel, the khan of the predominantly pagan Bulgarians. Tervel acceded to the request and helped Justinian regain his throne. Sadly, Justinian broke the peace, stabbing Tervel in the back by attacking his lands. This led to turmoil in the region and Justinian’s death in battle.

With chaos erupting in Byzantium, the Ummayad Caliphate saw it as a chance to invade. They made headway into Asia Minor and eventually found themselves at the gates of Constantinople.

Hemmed in from multiple sides, the new Byzantine emperor Leo III (or Leo the Isaurian) sought Tervel’s aid once more. Through shrewd and cunning diplomacy, Leo convinced Tervel to forget the past enmities and instead focus on a combined defense against the Arab hordes of the Ummayad Caliphate.

The Arabs, numbering between 80,000 and 120,000, suddenly found themselves at the end of a brutal beating. Their navies were smote by Greek fire from Byzantine ships. Meanwhile, the Bulgarians were able to attack their armies from the rear. Christian slaves recruited by the Arabs defected en masse. These actions led to the collapse of the Ummayad front, which lifted the siege of Constantinople.

Tervel’s actions earned him the title “Savior of Europe”—but more than likely, this unlikely alliance between the two nations saved Christianity as a whole. If Constantinople had fallen in this particular forgotten battle, Islam would have spread further into Europe. The spread of Christianity into the Balkans and Russia would have been extinguished almost immediately.

2The Fall Of Greece And The Rise Of Alexander At Chaeronea

338 B.C.

In a recent article, we mentioned how the Sacred Band of Thebes, an elite unit made up of gay couples, was instrumental in routing the Spartans at the Battle of Leuctra (371 B.C.). With Spartan dominance in the region finally broken, Theban supremacy began, putting the city-state above all others in Greece.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Macedonia, King Philip II had his eye set on Greek lands. Philip had once threatened to invade Sparta, saying that if he set foot in their lands he would level it to the ground. The Spartans laconic reply is the stuff of legend: “If.” Perhaps knowing that the Spartans, even in their weakened state, would prove to be a considerable challenge, Philip instead turned his attention to the rest of Greece.

Thus, the Greek alliance led by Thebes and Athens faced off against Philip of Macedon and his young son Alexander. The young would-be conqueror was only 18 years of age, but he had already earned enough of his father’s confidence to be placed in command of the left wing of the Macedonian forces. Historical recounting of the battle is mostly vague, though from what we know, Alexander himself was one of the first men to charge the Sacred Band.

The Macedonian and Greek forces fought a pitched battle the entire day and eventually one side had to give. It was the Greeks who blinked first.

The Athenians and Theban soldiers broke rank, but the Sacred Band held on bravely and were slaughtered nearly to the last man. By day’s end, as Philip surveyed the carnage, he congratulated Alexander then turned his eye on a row of 300 dead men lying where the Macedonian spears had cut them down. He was told that this was the Sacred Band, who stood their ground when all others had fled, protecting their lovers and avoiding shame. Upon hearing this, Philip broke down in tears.

1The Conqueror Who Walked Into A Trap For His Love

202 B.C.

The belief of Chinese superiority and its sphere of influence dates back to Confucian ideals, which were central to daily life during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220).

After their alliance and brotherhood toppled the Qin Dynasty, Liu Bang of Han and Xiang Yu of Chu were wary of each other’s intentions. During the Banquet at Hongmeng (or Hong Gate), both parties met to celebrate the end of the rebellion. One of Xiang Yu’s men suddenly performed a “sword dance,” brandishing his weapon and fluidly moving around the room until he could find an opportune moment to cut down the unsuspecting Liu Bang. Upon realizing the intention of the lieutenant, one of Liu Bang’s own men also “danced,” his swordplay meant to defend the Han lord.

After both parties departed, each knew that only one would live to rule the land.

By 202 B.C., the battles between the Han and Chu would reach a pivotal climax. Xiang Yu was a powerful and ferocious general; Liu Bang was a crafty leader. A plan was soon developed to ensnare the king of Chu.

Liu Bang and his ministers knew of Xiang Yu’s deep love for his concubine Yuji. She was said to have accompanied the warlord wherever he went. If she was captured, the Han strategists knew Xiang Yu would have no choice but to rescue her. They imprisoned her deep in a ravine in Gaixia (Kai-Hsia).

In one of history’s great tales of romance, Xiang Yu led 100,000 of his brave men straight into a trap. Deep in the valley, he caught sight of his beloved Yuji, and at once the Han deployed “an ambush from ten sides.” Xiang Yu rushed to Yuji’s side and was ready to die with her, but Yuji committed suicide so Xiang Yu could escape.

Maddened with grief, Xiang Yu departed with the survivors—down to 800 men—only to be trapped near a river by the Han forces. With his love gone and nowhere to go, Xiang Yu killed himself as well. This was the moment when crafty tricks and knowing one’s weaknesses toppled sheer military might, and the very reason why the Chinese refer to themselves as “People of the Han” rather than “the Chu.”

Jo considers The Battle of Manila in 1945 one of history’s forgotten battles. The battle, which led to the loss of 100,000 civilians, is barely mentioned in most classrooms in the Philippines today. Do you know of any forgotten or lesser-known battles from your region? Let him know at [email protected] or in the comments section.