Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Most Outrageous Things Benjamin Franklin Ever Did

Some call him “The Newton of Electricity,” and others call him “The First American.” Whatever the nickname, we can all agree Benjamin Franklin was one of a kind. After all, he invented his own alphabet, was a chess master, and there’s even a psychological effect bearing his name. (Although he never actually campaigned for the turkey to represent the US.) But these facts just barely scratch the surface of Franklin’s amazing life. Really, this guy needs an entire list dedicated to his crazy achievements . . . so here we go.

10The ‘Drinkers Dictionary’

Benjamin Franklin was a man who enjoyed his wine. While no heavy drinker, Franklin kept 1,200 bottles of Bordeaux, champagne, and sherry locked away in his Paris home. In one of his many letters, he declared that wine is “constant proof that God loves us, and loves to see us happy,” and even gave an amusing anecdote as to why the Lord brought about the Genesis flood.

“Before the days of Noah,” he wrote, “men, having nothing but water to drink, could not discover the truth. Thus they went astray, became abominably wicked, and were justly exterminated by water, which they loved to drink.” Of course, Noah saw through “this pernicious beverage,” and, after leaving the Ark, learned how to make wine and thus “discovered numberless important truths.”

Of course, Franklin did get a little tipsy now and then. In one humorous exchange, Franklin debated his own gout, an ailment that plagued him throughout his life. Evidently in pain, Franklin wrote, “What have I done to merit these cruel sufferings?” Gout smugly replied, “Many things; you have ate and drank too freely . . . ”

In other words, Franklin knew a thing or two about getting drunk. He also knew a few ways to describe getting smashed. In a 1737 edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette, Franklin published the “Drinkers Dictionary,” a list of 200 synonyms for getting plastered. Some of the more colorful expressions include, “He’s had a thump over the head with Sampson’s Jawbone,” “He’s contending with Pharaoh,” “He’s been too free with the Creature,” and “the King is his Cousin.” If you want something shorter, you could say he’s “wamble crop’d,” “fuzl’d,” “pungey,” or “trammel’d.” And then there’s my particular favorite: “He’s right before the wind with all his studding sails out.”

9Frankenstein And The Kite

What do Benjamin Franklin, frog legs, and the horror genre have in common? The answer is “electricity.”

Everyone knows how Benjamin Franklin flew his kite into a thunderstorm and proved lightning was actually electricity. Most people believe Franklin made his shocking discovery in 1752 with the help of his son, William. Using a silk string so he wouldn’t end up a “Fried Founding Father,” Franklin sent an iron key up into the atmosphere—and the rest is history.

Word of Franklin’s success spread around the globe and inspired an Italian physiologist named Luigi Galvani. Thanks to Franklin’s experiments, Galvani started zapping a bunch of dead frogs to see what would happen. As it turns out, the electricity activated the amphibians’ muscles, causing the legs to kick. In turn, Galvani’s research inspired showmen, who got their hands on human corpses and “awakened” the dead with electric current. These ghastly sideshows caught the attention of a young woman named Mary Shelley, who took Galvani’s discovery and turned it into the world’s most famous horror story. Some people even think the “Frank” in Frankenstein comes from Benjamin’s last name.

Only there’s one catch—some think Franklin’s experiment might’ve never happened. According to biographer Tom Tucker, the whole kite story is a big lie. In his book Bolt of Fate, Tucker says Franklin kept quiet about the experiment until the later years of his life. If he’d really proven lightning was electricity, why didn’t he tell everyone in the 1750s when it happened?

Tucker also tried to replicate Franklin’s experiment with a kite made from 18th-century supplies . . . and it never got off the ground. So perhaps Franklin made the whole thing up, or maybe Tucker is a really bad kite flyer. It doesn’t really matter, though, because Franklin wasn’t the first guy to conduct the experiment anyway. That honor belongs to a Frenchman named Thomas Francois-Dalibard, who got his kite in the air a month before Franklin’s.

8He Was A Military Commander

Believe it or not, Benjamin Franklin was an 18th-century Rambo. Sure, he never donned a bandana and went rampaging through the woods, but he did lead troops during the French and Indian War. It was 1756, and things were going poorly for the British. The French and their Native American allies (the Delaware and the Shawnee) were just mowing through English settlements, and when General Edward Braddock tried to stop them, they made mincemeat out of the guy. Seeing things were grim, Pennsylvania governor Robert Morris called on Franklin to lead a Philadelphia militia and go First Blood on the French.

Franklin’s first move was to build a fort at the Moravian settlement of Gnadenhutten. Leading an army of 170 men, Franklin made it through the wilderness, fighting off enemy attacks, and set about instructing his troops on building a proper fortress. After the fort was finished, Franklin cleared the area of the enemy and built additional strongholds. The whole time, Franklin was assisted by his son William, who had more military experience than his dad. Eventually, the two separated as William was a dedicated Tory, but at the time, they made a good team.

In addition to fighting the French, Franklin came up with ways to make his men better soldiers. For example, he encouraged scouts to take dogs into the woods in case they ran across any French soldiers. He was also concerned about the men’s spiritual state. When he noticed the soldiers weren’t attending church services, he started handing out the daily rum rations at the end of the sermons. Everybody got religious really fast. Most impressively, Franklin served as a military officer without pay. His devotion to duty made him a pretty popular fellow among his native Pennsylvanians, and the British were scared he might even lead his troops on Philadelphia and conquer the city. Of course, the English had nothing to fear. After all, Benjamin Franklin would never dream of rebelling against the crown.

7He Was A Security Risk

We like to think Benjamin Franklin was this incredibly perceptive guy, but sometimes this Founding Father wasn’t the best judge of character. And it could’ve cost America its independence.

The debacle started in 1776. Things were getting tense with Great Britain, and the colonists were busy wooing the French. As any history student knows, France played an important role in securing American independence. After all, they were one of the world’s two superpowers at the time, and that’s why the Continental Congress sent a Commission to Paris to cement their relationship with the French. The Commission included a merchant named Silas Deane, a lawyer named Arthur Lee, and Benjamin Franklin, who was the leader of the pack. They set up shop in the City of Lights and started rubbing elbows with French politicians, buying weapons, commissioning European supply ships, and churning out pro-American propaganda. But despite their hard work, Commission Headquarters weren’t exactly “secure.”

Top secret papers were lying all over the place, and Franklin discussed highly classified matters out in the open. Even worse, the Commission’s secretary was a guy named Dr. Edward Bancroft. A friend and protege of Franklin, Bancroft was quite the chemist, and Franklin even sponsored the guy for induction into the British Royal Society. Bancroft was also a British secret agent.

When no one was looking, Bancroft pored over classified documents, took notes with invisible ink, and used a dead drop to pass on info, all under Franklin’s nose. Shockingly, Arthur Lee actually suspected Bancroft was a traitor and warned Franklin about his buddy’s backstabbing ways. But Franklin disliked Lee and was close with Bancroft, so he ignored the lawyer’s advice, allowing the Englishman to report on troop movements and treaty information. Curiously, after the war finished, Franklin and Bancroft kept writing letters back and forth. The Founder never knew his protege was a spy. No one did until 70 years after Bancroft’s death . . . well, no one except Arthur Lee.

6Bones In The Basement

Even though he’s the quintessential American, Franklin lived in London for 16 years. The inventor rented out several rooms on the first floor of a Georgian house on 36 Craven Street and spent his days visiting famous friends, marching up and down the stairs for exercise, and puttering around his lab. It was here Franklin finished his lightning rod, worked on his famous stove, and took “air baths.” Believing air circulation was good for the body, Franklin would open his windows, strip down naked, and sit in the open, soaking up the cool air while horrified neighbors gouged their eyes out. But that was hardly the weirdest thing that happened inside 36 Craven.

In 2003, the “Friends of Benjamin Franklin House” wanted to restore Franklin’s old London home and turn it into a museum. But while they were working in the windowless basement, they made a grisly discovery: chopped up remains of 15 human bodies. There were mutilated leg bones and trepanned skulls. They found the skeleton of an elderly man and the bones of an infant, all buried in a hole 1 meter (3 ft) deep and 1 meter wide. Weirder still, they all dated back to the 1700s. So was Benjamin Franklin an 18th-century “Jack the Ripper”? While that’d make a great novel, the real culprit was probably a young guy named William Hewson. And no, he wasn’t a murderer.

Hewson was a scientist who ran his own anatomy school in Franklin’s basement. (Well, technically, the building belonged to Hewson’s mother-in-law, Margaret Stephenson.) Hewson more than likely had grave robbers snatch fresh corpses so he could teach his pupils about the human body, slicing and dicing along the way. When he was done, he’d dump the evidence into his little pit. But don’t think Benjamin Franklin was blameless. Chances are good the ever-curious scientist attended Hewson’s illegal lectures. As for the good doctor himself, Hewson tragically died of blood poisoning after nicking his finger during a dissection.

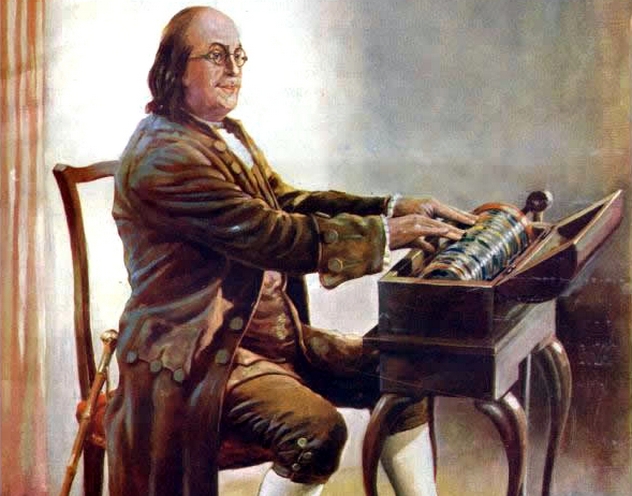

5Drinking Songs And The Glass Armonica

Benjamin Franklin was a musical man. He could play the harp, violin, and guitar, and he regularly showed up at concerts. He even possibly wrote his own string quartet. Of course, not all his musical endeavors were highbrow. In the 1740s, Franklin enjoyed writing drinking songs, setting lyrics to well-known tunes of the day. One of his ditties was “The Antediluvians Were All Very Sober,” in reference to people who lived before the Genesis flood. Commenting on their lack of alcoholic beverages, Franklin sang:

The Antediluvians were all very sober

For they had no Wine, and they brew’d no October;

All wicked, bad Livers, on Mischief still thinking,

For there can’t be good Living where there is not good Drinking.

But Franklin’s greatest musical achievement was the armonica. Back in the 1700s, musicians would create music by filling wineglasses with water and running their moistened fingers around the rims. After hearing a performance, a delighted Franklin wanted in on the action. Only in typical Franklin style, he was going to take wineglasses to the next level. Originally called the “glassychord,” the armonica was made of 37 glass bowls, each nestled inside a larger bowl (like Russian dolls). They were all connected by an iron rod which was hooked to a spinning device. When Franklin pumped a treadle underneath, the rod rotated, causing the glass bowls to spin. Then all Franklin had to do was wet his fingers, rub them against the glass, and voila, music!

At the time, the armonica was a big hit. Franklin showed it off at parties, and companies started mass producing the new instrument. One of the most famous armonica players was Marianne Davis, a musician who toured Europe. Marie Antoinette took a few armonica lessons, and even Mozart and Beethoven wrote their own songs for Franklin’s invention. Unfortunately, the armonica caused a few problems before it fell out of fashion. Some musicians believed the armonica sent vibrations into their brains, causing them emotional distress. Today, some suspect these performers were suffering from lead poisoning as there was most certainly lead in those glass bowls. As for the other problem—well—that has to do with our next entry.

4Franklin vs. Mesmer

In 1778, Benjamin Franklin was ambassador to France, but he had more on his mind than just independence. In fact, he was doing some important work for King Louis XVI. The young monarch was kind of concerned about a new fad sweeping across his kingdom. Known as “mesmerism,” this strange craze was wildly popular with the French aristocracy, including Queen Marie Antoinette. Developed by Franz Anton Mesmer, mesmerism was an early form of hypnosis that focused on “animal magnetism,” a fluid that Mesmer claimed flowed through all living things, like an 18th-century version of “the Force.”

According to Mesmer, this energy sometimes got trapped in the human body, leading to all sorts of sicknesses. To release the fluid, you needed Mesmer’s help (of course). Patients attended seminars where Mesmer darkened the lights and played soothing music, often with Franklin’s armonica. Once the crowd was in the right mood, Mesmer picked a patient—usually a woman—and stared into her eyes until she freaked out. People would scream, shake, and go into convulsions, releasing that alleged energy. And afterward, they felt fantastic.

King Louis was skeptical, so he appointed a team of scientists (including Franklin and the infamous Joseph Guillotin) to figure out whether Mesmer was a fraud. Their investigation culminated with an amazing experiment on Franklin’s lawn at his home outside Paris. The trial involved a 12-year-old boy and a bunch of trees. You see, Mesmer and his followers went around touching trees with magnetized rods, supposedly supercharging the plants and giving them healing powers. So the scientists wanted to blindfold the kid, lead him from tree to tree, and see if he could pick which one was magnetized. Well, the kid definitely felt something. By the time he reached the fourth tree, he was sweating and shaking on the ground. Only there was one catch: None of the trees were magnetized. Franklin and his friends had just conducted what some believe was the first placebo-controlled trial in history. The group then published a paper explaining those convulsions had nothing to do with animal magnetism. They were simply caused by overactive imaginations.

3He Was A Major Troll

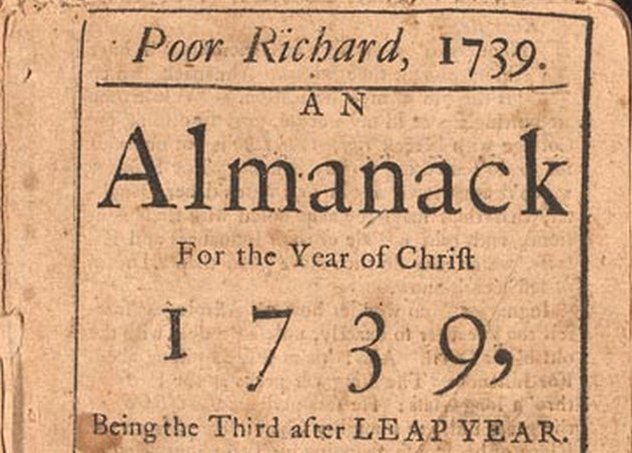

“Fish and visitors smell in three days.” “Early to bed and early to rise . . . ” “Three may keep a secret if two of them are dead.” We’ve all heard these words of wisdom, courtesy of Richard Saunders, author of Poor Richard’s Almanack. Back in the olden days, people read almanacs more than any other kind of secular book, and Poor Richard’s Almanack was the best of the best.

Of course, we know “Richard Saunders” was Benjamin Franklin’s pseudonym. The balding writer was the brains behind the annual pamphlet, a book that was the Weather Channel meets Reader’s Digest. The almanac served as a calendar, let readers know when the Sun was going to rise, gave advice to farmers, and was full of entertaining stories and pithy sayings. However, Poor Richard’s Almanack wasn’t the only almanac in the colonies. Another popular pamphlet was An American Almanack by Titan Leeds. Despite his epic name, Leeds was a lousy writer. Just take a look at this horrible poem: “Out of the Frying into the Fire / And he that’s not True must be a Lyar.”

The rest of the prose sounded just as stilted, but Leeds was still serious competition—so Franklin decided to take him out, troll-style. Poking fun at the American Almanack‘s fondness for astrology, Poor Richard’s made a prediction of its own, claiming that on “Oct. 17, 1733, 3:29 P.M., at the very instant of the conjunction of the Sun and Mercury,” Titan Leeds would kick the bucket. When October 17 rolled around, Leeds survived and then angrily attacked Franklin, calling him “a Fool, and a Lyar.” But Poor Richard’s wasn’t done trolling yet. In his next pamphlet, Franklin claimed there was no way a gentleman like Leeds would use such horrid language. That meant his rival had in fact died on October 17, and now someone was impersonating the late Mr. Leeds.

This back-and-forth went on for a long time, and the hoax drove up the sales of Poor Richard’s Almanack. Nevertheless, all good pranks must come to an end, and Titan Leeds finally passed away in 1738. But Franklin wasn’t done with the joke. In the next issue of Poor Richard’s, Franklin got the last laugh, declaring the villains who’d impersonated Titan Leeds had finally given up their little game.

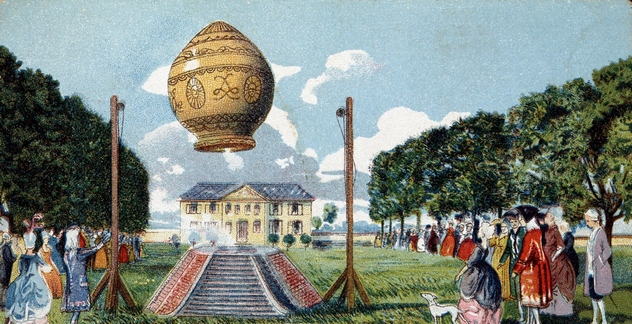

2Balloon Experiments

Benjamin Franklin lived in an exciting time. Not only were there revolutions, but people were making all sorts of scientific discoveries and technological innovations. Two of these pioneers were Jean Francois Pilatre de Rozier and Marquis d’Arlandes. On November 21, 1783, these Frenchmen became the first humans to break the bonds of Earth. They soared up into the sky in a hot air balloon, and Franklin was there to see it fly. As you might expect, balloons were all the rage in Paris, and Benjamin Franklin spent a lot of time figuring out practical uses for these big windbags. While his schemes were never put to use, they were pretty darn fascinating. For example, Franklin thought the military could use balloons to transport supplies across wide rivers. But that was only one of his ideas, and they get zanier from here on out.

Franklin though it might be a good idea to fill up a balloon with hydrogen and tie it around a servant. Why? Well, if you needed to send a message, that balloon would reduce the footman’s weight to “perhaps 8 or 10 Pounds,” allowing him to zip along the city streets and deliver the message in a timely fashion. Similarly, Franklin wanted to hook a balloon up to a chair so a servant could pull him down the street, although there’s no record that he ever tried it. (In fairness, Franklin had difficulty walking at this point and required four men to carry him to work.) Finally, Franklin wanted to use balloons to make an 18th-century icebox. Since the higher you go, the colder it gets, he proposed putting meat into a container, hitching it to a balloon, and letting the box hover up in the atmosphere where the meat would stay nice and fresh. He also thought it would be a splendid way to make ice. Unfortunately, Franklin died before he got a chance to actually ride in a hot air balloon himself.

1Benjamin Franklin, Tornado Chaser

In 1749, the folk along the Mediterranean Sea were freaking out. They’d spotted a waterspout off the coast of Italy, and people were terrified the world was coming to an end. Wanting to calm the masses, the Pope put his best man on the job, a science-minded priest named Father Ruder Boscovich. After some quick research, Boscovich wrote a book explaining how waterspouts were rare but perfectly natural. In other words, calm down, everybody. A few months later, in 1750, a London magazine published a review of Boscovich’s work, and soon people were sending copies of the article to Benjamin Franklin, asking for his opinion on these crazy waterspout things. Since Franklin didn’t know a lot about tornadoes, he started combing through articles in science journals, analyzing firsthand accounts, and networking with a team of amateur meteorologists, trying to find the truth about twisters.

Pretty quickly, Franklin discovered most scientists were wrong when it came to waterspouts. Many people believed they were made of water, but Franklin asserted they were actually giant columns of wind. And if they were made of wind, that meant they could swing up onto land. Of course, people thought Franklin was nuts. “Landspouts,” as Franklin called them, were quite rare in New England, and most of Franklin’s friends thought his theory was ludicrous. And when he wrote a treatise explaining his beliefs, the Royal Society turned their head and dismissed the whole thing. As you might expect, Franklin was frustrated, especially since he didn’t have any solid evidence to back his claims. In fact, he’d never even seen a landspout . . . well, not until 1754, anyway.

Franklin and his son William were on their way to visit friends in Maryland when they spied a whirlwind headed their direction. It was about 15 meters (50 ft) high and 9 meters (30 ft) wide at the top, and Franklin’s companions were a tad nervous. But instead of running away like a normal person, Franklin followed the twister on horseback. According to Franklin, “the whirl was not so swift but that a man on foot might have kept pace with it,” but it was spinning incredibly fast. Curious what would happen, Franklin attacked the twister with his riding whip. Obviously, the whirlwind didn’t react and just rolled into a forest, with Franklin beside the whole way. Eventually, he started noticing the “landspout” sucking up leaves . . . and then saw it was sucking up branches. That’s when he started to wonder if this was such a good idea. Finally, Franklin decided he’d seen enough, but William followed the twister until it disappeared. So yeah, you could say the Franklins were America’s first storm chasers.

Nolan Moore believes Benjamin Franklin got all his best ideas from an anthropomorphic mouse. If you want, you can send Nolan an email or friend/follow him on Facebook.