Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

10 Alchemists Who Created Strange Modern Legacies

Simply put, alchemy is the study of the transmutation of base metals into gold or other precious metals. While alchemist have long been relegated to the fringe, modern scientists are finding that the alchemists were just a little bit right. Not all the way, because there are plenty of alchemical theories that, if true, would mean we’re living in an entirely different world. In some instances, though, historic alchemists did have a lasting impact on the world around them—just not the way they expected.

10Zosimos Of Panopolis

Zosimos of Panopolis lived around AD 300, and at the time, there was a definite blending of different schools of religious, scholarly, and philosophical thought. The Romans were still cracking down on this new upstart religion called Christianity, and nobody really trusted the whole idea of magic.

Zosimos’s writings were among the first to try to reconcile the differing opinions and ultimately made alchemy a more respectable science, paving the way for alchemists centuries in the future. His science was called “Chemeia,” an Egyptian word meaning “black-earth” and standing for one of the basic elements and building blocks of the world. He links Chemeia to Chemes, the name of one of the characters in the Book of Enoch, supposedly the child of a fallen angel and a human woman.

According to Roman theory at the time, the occult sciences were the work of evil, bringing down all the ills which afflicted mankind. Zosimos put a different spin on it—the demons intent on keeping mankind in a haze of ignorant suffering are just hoping for the continued ignorance of man. Alchemy, then, becomes the way in which man learns how to manipulate the world around him, pushing back the shadow of ignorance and becoming liberated from evil.

He may have helped give alchemy and the sciences a fighting chance, but that doesn’t mean his actual work on alchemy resembles much in the way of science. According to his work, part of his understanding came in the form of a dream in which he spoke to a priest standing in front of an altar. The priest said that he had been flayed and mangled, his flesh and his bones burned and transformed from body into a pure spirit. Zosimos woke with the understanding that this was the process that the basic elements needed to go through to be transformed. When he fell asleep again, he saw the same place, with the bowl-shaped altar now filled with boiling water and screaming people. A copper man wrote on an iron tablet while the people in the water boiled to death. Zosimos interpreted all this as the giving and taking and transforming of all properties.

9Maria The Jewess

We know incredibly little about Maria the Jewess, also known as Maria the Hebrew or Maria Hebraea. What we do know of her comes from the writings of the above-mentioned Zosimos, who often quotes her in his own work. He doesn’t tell us when or where she lived, though—only that she was among the ancients from whom he learned.

There are some pretty basic teachings that form the fundamental core of her beliefs and the beliefs that would go on to shape alchemical practices. All things are basically the same; their final form is just a matter of how they’re combined. Man and metals are composed of the basic elements, and giving nourishment to, say, copper can create gold, just as nourishing a man perpetuates life. She also believed that objects like metals were male or female, and that metals could die just like people, plants, and animals. But death was just a change in form—when plants are burned, they die and change form and become ash or dyes. Expose metals to fire, and they change, too, releasing their souls in the form of vapor.

This brings us to her useful discovery, the one that the world is, even today, thankful for on a daily basis—the still. Maria is credited with discovering and first using what’s now been turned into the still, creating both the balneum Mariae (a double-vessel water bath for heating the substance in the inner vessel without scorching it) as well as the two-vessel variety of still, which is connected by a tube that allows for the collection of liquid and is still a favorite of moonshiners everywhere.

8Isaac Newton

Newton’s contributions to the regular, mainstream world of math and science are pretty well known, so we’re just going to take a look at his less publicized alchemical practices.

By the time Newton was working, alchemy was no longer cutting-edge research. It was archaic, medieval, and modern science had already left it in the dust. For Newton, though, it was still fascinating, and while he didn’t publish his alchemical research as he published his other findings, he still wrote a massive amount on it. Particularly, he thought he was on the trail of the Philosopher’s Stone.

A universal cure-all and transmutative agent, the stone was one of the end-game goals for many alchemists that came before him. Newton spent a huge amount of time sifting through the works of his predecessors and trying to decode what they had written. Most alchemists wrote in a sort of cryptic code that made their work read like a bad pulp fantasy novel. It wasn’t silver, it was “Diana’s Doves,” and the “menstrual blood of the sordid whore” is the ore of antimony . . . and so on. Since no alchemist wanted others to get their research, everyone’s codes were different, and Newton’s works are just as cryptic—even more so, since he uses some of the standard terms in a way that no one else did.

Once Newton’s alchemical documents came to light, researchers at Indiana University started poring over the documents and trying to translate them. In one, he describes how Saturn (typically used as the code for lead, but in Newton’s source material is actually an ore called stibnite) has its fetters untied, “then shal arise a vapour shining like pearl orient.” He talks about the shining Luna (silver) and the creation of the Green Lyon (also stibnite). The writing is incredibly romantic and about as far from a science textbook as you can get—especially from one of the great scientific and mathematical geniuses of the world.

Newton spent about 30 years trying to assemble all he could on the research of previous alchemists with the ultimate goal of creating the ultimate answer to the ultimate puzzle—and finding the skeleton key to the world’s mysteries.

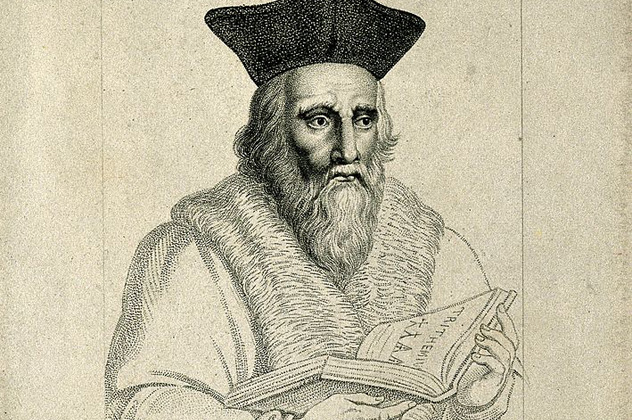

7Edward Kelley

A very mysterious figure, there’s more that we don’t know about Kelley than we do. We’re not entirely sure when he was born, whether or not he looked anything like the one portrait that was done of him, how he died, or how he spent much of his intervening years. The information we do have is often contradictory, but we do know that he made some pretty unlikely contributions in the form of inspiration for literature and theater. His life was so unlikely that it inspired works like Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist, and supposedly, he was one of Aleister Crowley’s previous incarnations.

We do know that he had a notorious partnership with John Dee, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth. Together, the alchemist and the magician claimed to be able to turn base metals into gold. In 1588, Dee wrote that Kelley had shown him the secrets of alchemy. By 1589, Kelley had established himself in the court of Emperor Rudolf II, and he’d been so well received in Prague that by the next year, he had lands, a title, and a knighthood.

While he was there, Elizabeth reportedly wrote to him repeatedly asking for just a bit of the special powder he had created to turn metals into gold, as she could really use it to help finance her army. The rumor was that he was able to put any metal into a crucible, add a mysterious substance, stir it, heat it, and produce gold. He was also reportedly in contact with angels who passed along some of their arcane knowledge.

Kelley’s success was about as short-lived as you might expect. According to one version of the story, he ended up involved in a duel with an official from the court in 1591. Dueling was illegal, and in spite of trying to make a run for it, he was arrested and imprisoned, where a broken leg was amputated. Just what happened next is largely disputed, but it’s thought that he was moved from one castle prison to another, and even though he received a pardon from Rudolf, he was in so much pain from his leg that he decided to end his own life by drinking poison. Other versions of the story say that it was Rudolf himself who ordered Kelley arrested and by no means gave him a pardon. In those stories, his arrest was due to his failure to follow through with his promised deliveries of massive amounts of alchemical gold.

6Jean Baptista Van Helmont

Alchemy and chemistry have always had a sort of strange relationship. At heart, they’re pretty similar. After all, they’re both sciences that use inherent properties to turn things into other things. The bridge between the two was built in large part by the work of a Belgian scientist working in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Originally studying to be a doctor, Jean Baptista van Helmont spent nearly a decade studying not only medicine but the effects of chemicals on the body. He’s the one who discovered carbon dioxide, made the first real advances in understanding the process of digestion, and had an incredibly unsuccessful medical practice, in large part because he never accepted payment for any medical treatments he administered. He also made some pretty impressive advancements in botany, and even while he was being investigated by the Spanish Inquisition, he measured the growth rate of a willow tree and compared it to the soil that it was planted in. Finding the soil unchanged while the tree grew larger, he was one of the first to prove that plants grew through absorption of water.

He also believed that understanding both the human body and the world that it existed in needed to start with alchemy. He believed that it was the basis for everything and that no advances could come until it had been unraveled. Part of his work—the search for the source of the life and growth of plants—was rooted in his alchemical beliefs. Van Helmont believed in the idea of a prima materia; instead of the idea of the basic elements, he thought there was one thing that formed the basis of life and, based on his plant research, he thought the prima materia for plants was water.

While he never claimed to have unlocked the secrets of making a Philosopher’s Stone, he did claim to have seen one in action. He described it as being the same color as “saffron in powder” and said that he once used it to turn 200 grams (8 oz) of quicksilver into gold.

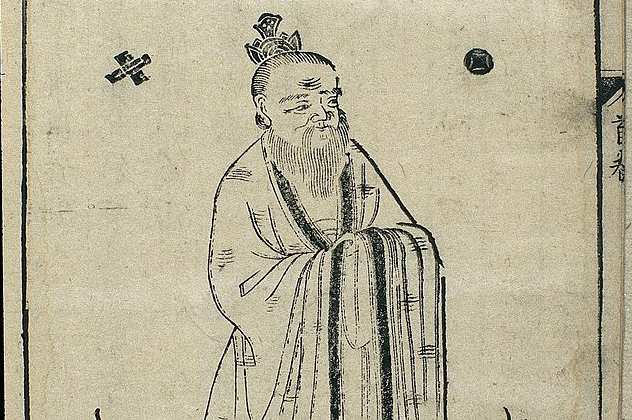

5Ge Hong

Sometimes, life delivers such a big helping of irony that you can’t help but wonder if there’s someone out there who’s just messing with mankind. Ge Hong was a Chinese alchemist living, writing, and working at the turn of the fourth century. He was born into a world of civil upheaval when words were so highly valued that he, with his southern speech and lack of eloquence, found himself struggling in a world that valued a more northern perspective. He did all right for himself, eventually being named Marquis of the Region Within the Pass, all in recognition of his military strategies and success. But he was really interested in philosophy, alchemy, and the idea that everyone could achieve immortality.

There were a few things he believed about what it took to become immortal, and at the top of the list was the idea that everything was surrounded by a “oneness,” and in order to channel that oneness, it took a huge amount of inner peace and serenity. There was also the enhancement of that energy, which he believed could be done by taking both herbal medicines and compounds that had been created through alchemy. Gold created from alchemical processes, said the theory, would never burn, decay, disappear, or otherwise die. And ingesting that gold would pass on those virtues to the human body.

Throughout the course of his alchemical experiments, he stumbled across something that would give the exact opposite of life. Buried in his writings is one of the first mentions of the combination of sulfur and saltpeter—the basis for gunpowder. Saltpeter was an incredibly common ingredient in Eastern alchemy, more so than in European works simply because it was much more commonly found in Asia. As early as the third century, alchemists discovered the telltale purple color that came from burning saltpeter, and it was Ge Hong who combined it with sulfur, clay, and a handful of other minerals in an attempt to create something that would turn lead into the alchemical gold that would give immortality. Real gunpowder wouldn’t come until much later—around AD 850—but there’s something wonderfully ironic about the groundwork for the basis of modern weapons being laid by an alchemist searching for everlasting life.

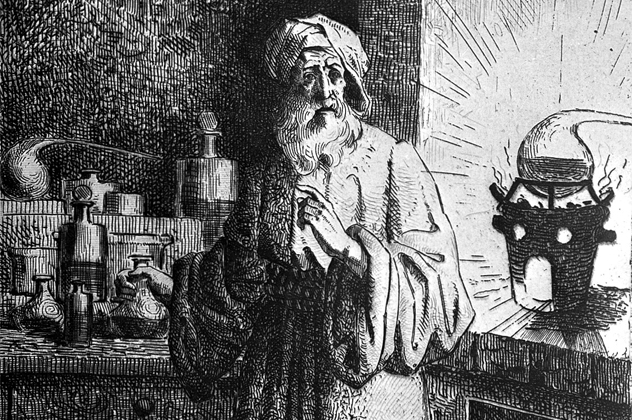

4Paracelsus

Paracelsus was a strange combination of chemist, alchemist, and forward-thinking physician. The beginning of the 16th century was a time when it was still pretty widely accepted that all of the body’s ills were governed by the four humors, a theory put forth by the ancient Greeks. A lot of Paracelsus’s alchemical work was based in the idea that there were four elements—earth, air, water, and fire—and that there was also a series of natural spirits that represented each of these groups—gnomes, sylphs, undines (nymphs), and salamanders, respectively. We can’t see them, even though they inhabit the world alongside us. They lived in absolute harmony because they weren’t capable of crossing the boundaries between the elements, and they lived between 300 and 1,000 years, with the earth elementals, the gnomes, having the shortest lives.

But at the same time he was writing about the nymphs and the gnomes, he was burning medical textbooks that had been written by the old Greek masters. He believed that the human body was, at its most basic, little different from the materials that were the basis of alchemy. Much like lead could be transformed into gold, he thought, the body’s organs could be transformed from sick to healthy with the same sort of principles. And that meant using chemicals in the body just like chemicals were used in the alchemy lab.

And it makes a lot of sense. This mixture of alchemy and medicine is what became toxicology, and Paracelsus was the first to apply alchemical experiments to the human body—like the use of mercury to treat syphilis. The naysayers (pretty much everyone at the time) were horrified at the idea that inorganic materials could be used in the body, while Paracelsus insisted that instead of rehashing all the old texts, they needed to open their eyes, observe, and experiment.

While the theory was a sound one that ushered in the development of a whole new science, most of the things Paracelsus was prescribing weren’t really the cures that he thought they were. Some of the chemicals that he was prescribing for people included mercury, arsenic, and lead. Famous for saying that poison was just a matter of the dose, he also made another major discovery that would change a different part of the world forever—he created laudanum.

3Johann Friedrich Bottger

Bottger lived at the turn of the 18th century, and like many of his contemporary alchemists, he was viewed as either a man with the power of magic or an absolute fraud. Only 19 years old when he was summoned to the court of Frederick Augustus I, he was ordered by the king to make good on his claims that he could turn base metals into gold. It turned out that the country was absolutely broke, and when your country is broke, going around claiming you can conjure gold isn’t necessarily the best life choice.

Bottger’s first reaction was to try to flee the country, but he was caught and returned to house arrest and ordered again to get down to the gold-making if he wanted to keep his head. Fortunately for him, the king was apparently a pretty understanding sort, for he was allowed to labor at the task for years.

In 1709, he didn’t quite make the sort of gold he was going for, but he did make another type: white gold. Porcelain had been developed in China as far back as AD 620, but its manufacture was a closely guarded secret. Porcelain made its way to Europe in the 1300s, and it was as good as gold. Importing it was the only way to get it, so having a set of porcelain meant you had money to spend. It earned its nickname of white gold and was in great demand by the upper echelons of society.

Artists and artisans had been trying for decades to make porcelain in Europe, and they had failed pretty consistently . . . until the alchemists got involved. Bottger, along with the more traditionally accepted scientist Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, first hit upon the production of a heavy, red stoneware. But his next discovery—a perfect replica of Chinese porcelain—was enough to keep his benefactor happy and led to the creation of European porcelain, the next best thing to real gold.

2Robert Boyle

The work of Robert Boyle is often taught as serious stuff, with the Irish scientist credited as being one of the fathers of modern chemistry. He worked with vacuums and air pumps, struggling to get his contemporaries to embrace this new way of thinking.

And, like Newton, he also dabbled in alchemy. A lot.

Like many of those contemporaries, he wasn’t just working in the sciences—he was trying to find a way to marry science and religion. In his articles in Philosophical Transactions, he talks about reports of supernatural phenomena and justifies their existence by arguing that the supernatural was proof of God’s actions on Earth. Alchemy, therefore, was sort of a bridge between what was scientifically possible and the manifestation of God’s power, which we obviously can’t entirely understand.

Some of his earliest writings suggest that one of the first sparks that ignited Boyle’s interest in science was the search for the Philosopher’s Stone. Letters to his sister lament his failure to discover the stone, and while it’s debated just how serious he was being, he also wrote papers on his own attempts at transmutation. When he created a solvent that could dissolve gold, he talked about it in the context of not only turning part of it into silver, but in terms of it being Philosophical Mercury, which has long been one of the first steps in creating the elusive Philosopher’s Stone.

Boyle’s work also follows hand in hand with the alchemical treatise The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine. The 12 steps are supposed to be the steps to creating the stone, but they’re so encrypted that the process isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. Like Newton’s, Boyle’s alchemical leanings were only recently explored, as he also used cryptic codes to hide the truth of what he was exploring.

1Hennig Brand

Throughout history, we’ve looked at the world around us in some pretty strange ways. Human excrement, after all, wasn’t always a waste product, and for 17th-century alchemists, it was an incredibly valuable raw material. German alchemist Hennig Brand might not have found literal gold in his golden showers, but he did find something else that changed the face of science forever—phosphorus.

In 1669, Brand was working on the age-old problem of creating gold. Born in 1630, serving as a soldier in Germany for a short time, and eventually marrying a wealthy woman, Brand retired from his job as a glass-maker to take up alchemy. After his first wife died, he married a second wife (also rich) and recruited her son to help him in the lab he’d already been setting up. He had a theory that water was the basis of life. He said that water had some pretty mystical qualities to it, and water that had passed through the human body should be extra mystical. He believed that he had stumbled upon one of the missing components for turning base metals into gold, and he began his experiments.

Over the course of those experiments, he went through about 5,600 liters (1,500 gal) of urine. Just how he got it is up for debate, though it’s claimed that he preferred to use urine from people who drank a lot of beer because of the golden color. It’s not known exactly what he was doing with all that urine, either, but it’s thought that he first let the buckets bake in the sun, and there was undoubtedly a lot of boiling and extracting of some of the layers that separated during the various processes. When he distilled his final product, he found that he had made a white powder that smelled like garlic and burst into flame when it was exposed to the air.

It’s not a coincidence that the Philosopher’s Stone and phosphorus have similar names. Brand was convinced that the weirdly flammable substance was the Philosopher’s Stone, and he named it phosphorus, the light-bearer. He mucked about with it for six years before he finally admitted to himself that while he wasn’t going to be using it to turn anything into gold, it was still pretty handy when it came to producing light. We still use it that way today every time we strike a match. Fortunately, we don’t need to use urine anymore.