Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Top 10 Ancient Pain Relievers

Many believe that patients before the early 20th century had to endure dental repairs, tooth extractions, or general surgery in agony, largely unrelieved except by slugs of whiskey or wine. Archaeology suggests that such was not the case—at least, not for everyone.

Some of our ancient ancestors were quite creative when it came to medicine. Although we don’t know exactly how they acquired their knowledge and beliefs, they made good use of natural substances when it came to relieving or blocking pain.

10 Opium

As far back as 3400 BC, opium poppies were grown in lower Mesopotamia. The ancient Sumerians called the poppy Hul Gil (“joy plant”), suggesting that its euphoric and anesthetic properties were known to them.

The knowledge involved in collecting poppies and extracting opium from them passed from the Sumerians to the Assyrians to the Babylonians to the Egyptians. By 1300 BC, the ancient Egyptians were cultivating their own poppies. The opium trade thrived during the reign of pharaohs Thutmose IV, Akhenaton, and Tutankhamen.

In 330 BC, Alexander the Great brought opium to the Persians and the Indians. Starting around 1300, opium’s use was suppressed throughout Europe as “demonic,” but by 1527, it was again employed for medicinal purposes.

As an anesthetic, opium was a great boon. But it was also used for recreational purposes and was involved in smuggling, drug trafficking, and other criminal enterprises. To this day, depending on its use, opium continues to be regarded as a benefit or a menace to society.[1]

9 Henbane

Like some other herbs and flowers used for medicinal purposes, Hyoscyamus niger, which is better known as henbane, can have psychotropic effects. Even so, it’s been used as an anesthetic since ancient times.

Like other Hyoscyamus species, henbane contains both atropine (a poison found in plants of the nightshade family that is used as a muscle relaxant) and scopolamine (a poisonous alkaloid used to prevent vomiting, calm individuals, or induce sleep). Henbane was used in the first century AD to allay pain.

In ancient Turkey, henbane was called beng or benc. Taken as a pill or smoked, it was used to relieve toothaches, earaches, and other maladies.

As a toothache remedy, henbane was used to fumigate the mouth. After a patient rinsed his or her mouth with warm water, henbane seeds, which are especially rich in atropine and scopolamine, were sprinkled over hot coals. The rising smoke entered the mouth, alleviating the pain of the toothache.[2]

8 Acupuncture

The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine (c. 100 BC) is the first text in which acupuncture is set forth as “an organized system of diagnosis and treatment.” Written partly in a question-answer format, the document presents questions by the emperor, who is answered by his minister Chhi-Po.

The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine (c. 100 BC) is the first text in which acupuncture is set forth as “an organized system of diagnosis and treatment.” Written partly in a question-answer format, the document presents questions by the emperor, who is answered by his minister Chhi-Po.

The document is likely based on centuries-old traditions embedded in Taoist philosophy. It mentions life force channels (meridians), a concept important to treating various conditions by inserting needles in precise locations associated with these channels.

The practice fell into disfavor in the 17th century and was outlawed in 1929. It became respectable again in 1949, when it was reinstated as a medical alternative. Thereafter, the use of acupuncture spread to Japan and throughout Europe and the United States, although little clinical research supports acupuncture’s effectiveness in treating pain or other conditions.[3]

According to theory, a variety of needles are inserted into any of hundreds of points throughout the body to balance the flow of yin and yang through the body’s meridians.

Critics of the procedure suggest that its effectiveness as an anesthetic and as an agent for treating other conditions is mostly due to placebo effects. However, it’s possible that some acupuncture points could be “trigger points that [do] stimulate physiological responses in the body.”

7 Mandragora

One of the first anesthetics to actually render patients unconscious appears to be Mandragora. Greek physician Dioscorides (AD 40–90) wrote of this effect in the first century AD when referring to Mandragora wine. The wine was made from the mandrake plant and caused a profound sleep to overtake surgical patients. Dioscorides described the sleep thus induced as “anesthesia.”

In 13th-century Italy, Ugo Borgognoni (Hugh of Lucca) introduced the use of the “soporific sponge” (aka “sleep sponge”) to induce an anesthetic sleep. “A sponge was soaked in a dissolved solution of opium, Mandragora, hemlock juice, and other substances [before being] dried and stored.”[4] After being moistened, it was held over the patient’s nose until its fumes caused him to lose consciousness.

6 Datura

Although it was derived from a poisonous plant, Datura (thorn apple or jimsonweed) was a popular ancient pain reliever and sleep inducer. It’s mentioned in medical texts by Dioscorides (AD 40–90), Theophrastus (370–285 BC), Celsus (fl. AD 37), and Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79).

The drug had several serious side effects. A drachma (3.411 grams) taken with wine could cause hallucinations, while two drachmas could cause madness for as long as three days. Greater quantities could cause permanent insanity or even death.

Although Datura was effective in relieving patients’ pain during ancient surgical procedures, it also resulted in their deaths when it was improperly administered. For this reason, another popular name for Datura is “Devil’s apple.”[5]

5 Ethylene

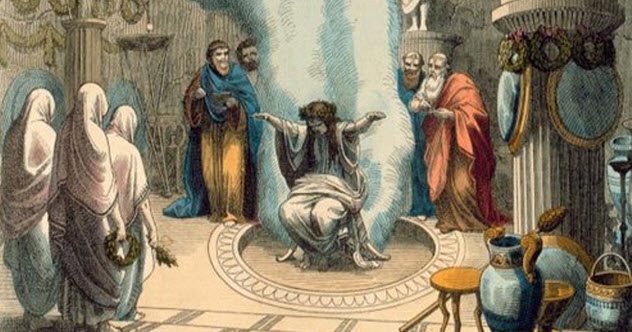

At the oracle of Delphi, the Pythian priestess of Apollo uttered prophecies after inhaling gases from fault lines beneath the Sun god’s temple. Those gases might have included ethylene, an anesthetic administered through inhalation.

In 1930, ethylene was being hailed as the “new” general anesthetic. It would replace chloroform, which was on its way out due to serious post-op effects such as sudden death, and ether, which often resulted in nausea and vomiting following surgery.

According to a surgeon who’d used ethylene in 800 surgeries, the substance rendered patients unconscious within “three to eight minutes . . . usually without any excitement or feelings of suffocation.” The patient recovered from its effects just as quickly once the anesthesia mask was removed.

The use of ethylene had many other benefits, too. Since ethylene was “less toxic on the nervous system or body cells,” it was also unlikely to produce headaches. It didn’t irritate the patient’s lungs, adversely affect blood pressure, or cause excessive bleeding or post-op sweating. Ethylene also produced less acidosis (excessively acidic tissues or body fluids) and rarely caused gas pains.[6]

However, ethylene did have some drawbacks. On the minor side, it had a fleeting odor. More seriously, it was extremely explosive, which ruled out its use with thermocautery (cauterization with a heated instrument), the presence of open flames, and surgery in an X-ray room.

But ethylene could be used for any other type of operation. No doubt, Apollo’s priestess would have agreed with the surgeon’s assessment of the vaporous anesthetic.

4 Cannabis

As far back as 2900 BC, Chinese Emperor Fu observed that cannabis was known to be a pain reliever. The herb was among the entries in the Rh-Ya, a 15th-century BC Chinese pharmacopoeia that was essentially an encyclopedia of drugs. From China, the practice of using cannabis to alleviate pain spread to other regions of the world.

About 1000 BC, Indians began to mix cannabis with milk to create a painkiller known as Bhang. Later, cannabis was used to alleviate pain associated with earache, swelling, and inflammation.

By AD 200, Hua To, a Chinese doctor, prepared an anesthetic by mixing cannabis with resin and wine, making the abdominal, loin, and chest surgeries he performed almost painless.[7] By AD 800, Arabic physicians used cannabis to relieve the pain of migraine headaches.

3 Corydalis Plant

In ancient China, the tubers of the Corydalis plant were dug up, boiled in vinegar, and used to alleviate the pain caused by headaches and backaches. A member of the poppy family, the Corydalis plant grows mostly in central eastern China.

According to modern scientists, it’s an effective analgesic because it contains dehydrocorybulbine (DHCB), a natural painkilling compound. “This medicine goes back thousands of years, and it is still around because it works,” said Olivier Civelli, a pharmacologist at UC Irvine.[8]

Ancient Chinese doctors believed that the Corydalis plant remedied pain because it improved the flow of the life force chi. Current research has shown that DHCB acts in a way similar to that of morphine. However, DHCB acts on receptors that bind dopamine rather than on morphine receptors. Also, unlike morphine, DHCB is not addictive.

Ironically, a plant used for centuries in China may provide new ways to alleviate pain in modern patients. Scientists believe that the DHCB produced from the Corydalis plant’s tubers may become the drug of the future in combating several types of pain.

2 Carotid Compression

One of the means of alleviating pain was to render a patient unconscious. Ancient doctors sometimes squeezed the carotid arteries in their patients’ necks, thereby reducing, if not temporarily shutting off, the blood flow from the heart to the brain.

Aristotle wrote of the effectiveness of carotid compression in causing unconsciousness. “If these veins [sic] are pressed externally, men, though not actually choked, become insensible, and fall flat on the ground.”

The ancients’ awareness that unconsciousness could be produced in this fashion is indicated by the fact that the word karotids or karos means “to stupefy or plunge into a deep sleep.” Rufus of Ephesus (c. AD 100) claimed that the neck arteries were called carotid arteries because the compression of them caused stupor or sleep.

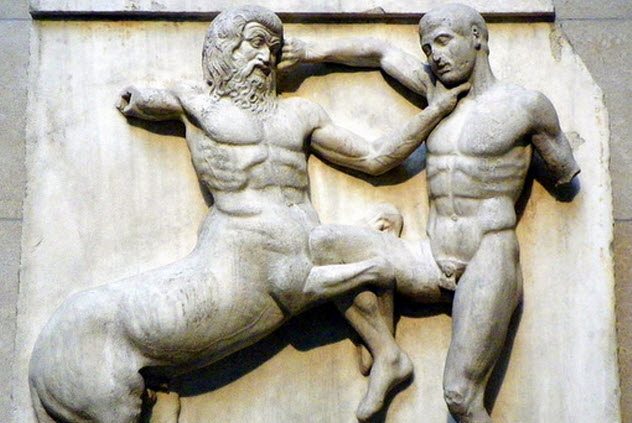

A sculpture on the south side of the Parthenon in Athens shows a centaur compressing the left carotid artery of a Lapith warrior. This also indicates that the ancient Greeks were aware of the effectiveness of this technique in rendering an individual unconscious. The same maneuver that was used in war was sometimes employed in medicine.[9]

1 Willow Bark

For centuries, the bark of the willow tree was used as an anti-inflammatory remedy that relieved pain. White willows grew along the Nile’s riverbanks, providing a ready source of bark.

The Ebers Papyrus, a compilation of medical texts dating from about 1500 BC, described the bark’s use as a painkiller. The ancient Chinese and the ancient Greeks also used willow bark for this purpose. Dioscorides noted its power to reduce inflammation.

Modern research suggests that willow bark is an effective painkiller because it contains salicin, “a chemical similar to aspirin.” Studies have also found willow bark to be more effective in treating pain than aspirin and at lower quantities. Due to its effectiveness, this centuries-old remedy is still used to relieve pain due to headache, backache, and osteoarthritis.[10]

Gary Pullman, an instructor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, lives south of Area 51, which, according to his family and friends, explains “a lot.” His 2016 urban fantasy novel, A Whole World Full of Hurt, available on Amazon.com, was published by The Wild Rose Press.

Read about more interesting ancient medical practices on 10 Secrets Of Ancient Medicine and 10 Ancient Egyptian Medical Practices We Still Use Today.