Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

10 Remarkable People Who Escaped From Auschwitz

The most infamous of all the Nazi concentration camps was Auschwitz, where over one million people died. With the heavily guarded main gate, watchtowers, and rows of electrified fences, escape was virtually impossible.

Of the estimated 900 inmates who tried to flee the camp, the majority were captured and executed. And yet, a total of 144 people managed to escape from the death camp and survive. Here are 10 people who escaped from Auschwitz and lived to tell their stories.

10 Eugeniusz Bendera

When the famous Auschwitz escapee Kazimierz Piechowski fled the camp, he was accompanied by three other men who are far less known. Eugeniusz Bendera was one of these men. Although many details of his early life are unknown, he displayed as much bravery as Piechowski in coordinating the escape.

Bendera was a Ukrainian man who worked as a car mechanic in Auschwitz, where he and Piechowski became friends. When a resistance worker in the camp told Bendera that he was slated for execution, he went to his friend Piechowski, a former Boy Scout and another resistance member.

Together, the two men devised an escape plan.[1]

On June 20, 1942, Piechowski and Bendera, along with two other men, pushed a cart brimming with garbage through the main camp and into a storage block. While three of the men stole officers’ uniforms, Bendera went to the garage with a duplicate key, got behind the wheel of the fastest car in the camp, and drove to where his friends were hiding.

As the car approached the main gate, Piechowski shouted at the SS guards to open the gate. When the guards complied, the four men drove out of the camp. They drove on country roads for hours. Then they abandoned the car and escaped into a Polish forest. Ultimately, Bendera settled in Warsaw, where he remained until he died in the 1980s.

9 Tadeusz Wiejowski

The first person to successfully escape from Auschwitz was a Polish shoemaker named Tadeusz Wiejowski. He had arrived at the camp on the first prisoner transport on June 14, 1940. He was assisted in his escape by five Polish workers who were employees of the camp.

On July 6, 1940, Wiejowski disguised himself as one of these workers and walked out of the camp with them. After they were outside the camp, the men gave him food and money and Wiejowski boarded a freight train leaving the area.[2]

The five Polish workers were interrogated in Auschwitz for assisting him, where four of them died. The fifth man died soon after the war ended. After his escape, Wiejowski returned to his hometown and lived in hiding for a year. He was discovered and sent to the Jaslo jail, where he was later executed.

8 Rudolf Vrba

Rudolf Vrba, who was born in Czechoslovakia in 1924, provided the first eyewitness account of Auschwitz and revealed the truth about the camp. In 1942, he was arrested and deported to the Majdanek concentration camp and later to Auschwitz.

When it was discovered that he could speak German, Vrba was sent to work in a storeroom, where he sorted the possessions of the people murdered by the Nazis. He later managed to become the camp registrar and saw firsthand the horrors of the gas chambers and the crematoriums.

In 1944, Vrba and another prisoner, Alfred Wetzler, hid under a pile of logs at a construction site. From time to time, they heard search dogs sniffing around the pile. After three days, the men made their escape from the camp at night and crossed into Slovakia.

At Zilina, Slovakia, they met with Jewish leaders and drew up a report on the truth about Auschwitz. The report was sent to the US and British governments, the Vatican, the Red Cross, and Hungarian Jewish leaders.

In the report, Vrba warned that the Hungarian Jews were scheduled to be transported to Auschwitz. Tragically, the Hungarian Jewish leaders failed to issue a warning to their community and hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were killed by the Nazis.[3]

After the war, Vrba married, had a daughter, and settled in British Columbia. There, he became a professor of pharmacology.

7 Jerzy Bielecki

Jerzy Bielecki was a Polish Catholic man who escaped from Auschwitz in 1944, saving the life of a young Jewish woman in the process. He had arrived at Auschwitz in 1940 and was one of the first inmates at the camp.

Bielecki was sent to work in the grain warehouse. In 1943, he met a young woman named Cyla Cybulska, another inmate who worked in the warehouse repairing burlap sacks. They began to communicate with each other secretly and ultimately fell in love.

Knowing that Cyla’s life was in danger, Bielecki began to devise a plan for them to escape. He acquired an SS uniform, a forged pass, and a document stating that he was a guard bringing Cyla to work on a farm. The ruse worked, and he and Cyla were able to exit through the main gate.

For 10 days, they made their way through fields and eventually went into hiding at the house of Bielecki’s uncle. Near the end of the war, they decided to go their separate ways to avoid recapture. But they vowed that they would find each other after the war ended.[4]

Cyla was told, incorrectly, that Bielecki had been killed. He was told that Cyla had fled to Sweden and died. The reports were wrong. The pair reunited in June 1983, though they did not rekindle their romance. In 1985, Bielecki was given a Righteous Among the Nations award from Yad Vashem for aiding Cyla, a young Jewish woman.

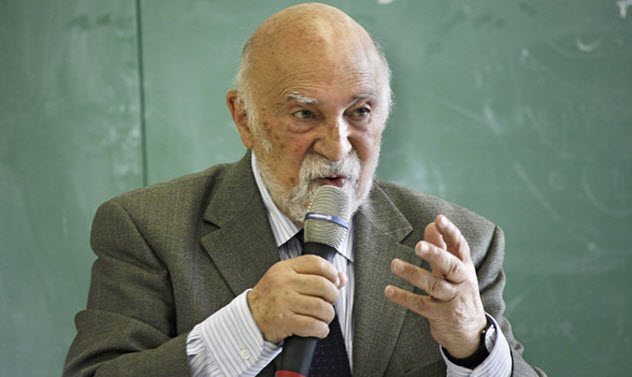

6 Simon Gronowski

Simon Gronowski, a young Jewish boy from Belgium, was just 11 years old when he and his mother were shoved into a cattle car headed for Auschwitz. Simon’s father had escaped from the Nazis, and the young boy was determined to join him. A group of men in the cattle car managed to force open the door of the moving train, and Simon jumped out.

The train slowed, and when shots rang out in his direction, Simon raced for the forest. He spent the entire night stumbling through woods and fields. Eventually, he found a village, where he knocked on one of the doors and met a woman who brought him to the local police.

The policeman, Jan Aerts, suspected that Simon had escaped a Nazi transport and decided to help him. He gave Simon food and clean clothes and put him on a train to Brussels, where his father lived. Simon reunited with his father, and they survived the war in hiding with Catholic families.

Tragically, Simon’s mother, Chana, and his sister, Ita, were murdered in Auschwitz. Simon settled in Brussels after the war, became a lawyer and jazz musician, and later married and had a family.[5]

For 50 years, he rarely spoke about his wartime experiences. Then he agreed to write a book. He also began speaking at schools, urging children to protect freedom and work for peace in their country.

5 Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki has the distinction of almost certainly being the only person to volunteer for Auschwitz and then escape from it. He was a 39-year-old Polish war veteran who fought against the Nazis and joined the Polish resistance.

After hearing horrific accounts about Auschwitz, the resistance decided that they needed to send someone to the camp to gather information. Pilecki volunteered. Using an alias, he allowed himself to be arrested in 1940.

Pilecki remained in Auschwitz for three years. He gathered information and secretly composed three reports about life in the camp, including its transition from a prison to an extermination camp. He also managed to arrange a resistance network of more than 500 inmates inside Auschwitz, which he called the Union of Military Organization.

In April 1943, Pilecki decided to plan an escape in the hopes of persuading the Polish resistance to launch an attack on the camp. On April 26, he and two other inmates were working in the bakery, which was outside the camp. When the SS guard wasn’t paying attention, they managed to get outside and run away.

Pilecki made it back to Warsaw but failed to convince the resistance to attack Auschwitz. He participated in the Warsaw Uprising, after which he was arrested by the Nazis and taken to a prisoner-of-war camp.

Pilecki was liberated by the US Army in April 1945. Soon after, he joined the II Polish Corps in Italy as an intelligence officer. In 1947, he was arrested by Polish communist authorities, interrogated, and tortured. He was later given a show trial and executed by the communist regime.

To this day, his burial place remains unknown, although it is suspected to be in Warsaw’s Powazki Military Cemetery.[6]

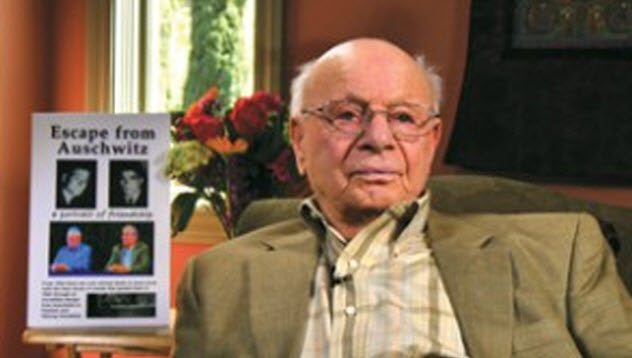

4 Herman Shine

Herman Shine managed to successfully escape from Auschwitz along with his childhood friend, Max Drimmer. Shine was born to a Jewish family in Berlin, but he was denied German citizenship because his father had been born in Poland.

Shine and Drimmer were deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1939 and then to Auschwitz in October 1942. Both young men were assigned to be construction workers in the Buna/Monowitz subcamp, which was located outside Auschwitz.[7]

On the construction site, they met a Polish civilian worker named Jozef Wrona, who coordinated an escape plan with them. They made their escape on the night of September 20, 1944, when they hid in a ditch. Later, they made the 16-kilometer (10 mi) walk to Wrona’s farm.

There, they hid in the barn for four months until the Soviet Army began pushing back the Germans. Then the men stayed with another family in Poland until the war ended. Eventually, the two friends made it back to their hometown of Berlin.

Shine and Drimmer later married their girlfriends in a joint wedding, and both couples immigrated to California. The two men dedicated much of their lives to Holocaust education and relating their story. After Drimmer died, Shine continued to share the story of their escape from Auschwitz and their remarkable lifelong friendship.

3 George Ginzburg

George Ginzburg was born into a Jewish family from Berlin. After the Nazis came to power, he joined the German resistance movement. He was arrested in 1942 for his anti-Nazi activities and spent three months in jail. Ginzburg was then sent to the main camp at Auschwitz, where almost no one survived.

Many years later, Ginzburg said that he was one of the lucky ones. Since he had been a motor mechanic, he was assigned to work at one of the factories offsite.

In 1945, as the Russian army closed in, the SS panicked and forced 58,000 of the Auschwitz inmates, including Ginzburg, on a two-day march through the snow to waiting trains. On this march, Ginzburg saw that the Nazis were badly disorganized and he searched for an opportunity to escape.

He picked up old cigarette butts left by the guards and rubbed them over his body to mask his scent in case dogs were sent after him. He shoved a stick under his blanket so that it resembled a hidden rifle and pretended to be a German official.[8]

Then Ginzburg approached a German guard and asked for a cigarette. When the guard went to ask a fellow soldier for one, Ginzburg hurried away and rolled down a snowy hill. He wandered alone through a forest.

When he found the body of a dead Russian soldier, he took the uniform and put it on. After two days, he was found by Soviet soldiers, who took him in and fed him.

Eventually, Ginzburg returned to Berlin and found his mother, who had survived the war in hiding. He worked as an interpreter for the US Army, served on the Israeli police force, and ultimately immigrated to Australia to start a new life.

2 August Kowalczyk

August Kowalczyk was a soldier in the Polish army and was taken as a prisoner of war by the Germans in 1940. They sent him to Auschwitz, which was mainly a prison for Polish dissidents and prisoners of war at that time.

On June 10, 1942, Kowalczyk was one of 50 prisoners who tried to escape from Auschwitz. The men were assigned to work in the fields that day and attempted to flee the guards, but most of the inmates were killed as they raced toward freedom.

Kowalczyk was one of the nine lucky ones who managed to successfully escape from Auschwitz that day. He went into hiding with various families, only 12 kilometers (7 mi) from the camp. After seven weeks, he managed to join a branch of the Polish Home Army in the Miechow area.

After the war, Kowalczyk became a successful stage and movie actor in Poland. He was known for his one-man play Prisoner 6804, in which he related the story of his escape. He often performed this drama in front of students at over 5,000 schools throughout Poland.

Kowalczyk died at age 90 in 2012, a brave man who devoted much of his life to bearing witness to the horrors of Auschwitz.[9]

1 Jan Komski

Born in Poland in 1915, Jan Komski escaped from Auschwitz and later survived four additional concentration camps. He was a talented artist and graduated from the Krakow Art Institute in 1939, not long before the Nazis invaded Poland.

In February 1940, Komski made up his mind to leave Poland and escape to France, where a Free Polish Army was being established. He was captured by the Germans on his way to France and sent to Auschwitz.

Komski arrived in Auschwitz in June 1940 on the first transport to the camp. He was assigned the number 564. Komski was put to work in the office of architecture and assisted in the expansion of the camp.

By that winter, there were more than 150,000 prisoners in the camp, most of whom were dead by the time Komski escaped in 1942. He and three other inmates launched their daring escape on the morning of December 29, 1942.

One of the men, Kuczbara, dressed in a stolen SS uniform and rode in a horse-drawn cart. The other three inmates, still dressed as prisoners, walked beside the cart. They approached the front gate, and Kuczbara displayed a counterfeit pass at the checkpoint.

The guards were fooled, and the men were able to pass through the gate and out of the camp. They made their way to the home of a Polish resistance fighter, who gave them clothing and a place to hide.

But this was not the end for Komski, who was arrested again in Krakow. As he was carrying different identity papers, he was not recognized and his life was spared. He was sent to prison and then spent time in four different camps: Buchenwald, Gross-Rosen, Hersbruck, and Dachau. Komski was at Dachau when the camp was liberated by the US Army.[10]

After the war, Komski was sent to a displaced persons camp in Munich where he married a woman who was also an Auschwitz survivor. They immigrated to the United States and ultimately settled in Washington, DC. There, he worked as an artist for The Washington Post for many years. He continued painting until he died in 2002 at age 87.

Tara Malone is a freelance blogger whose areas of interest include psychology, Jewish history and practice and greyhound rescue. She is a Holocaust educator and creator of the blog Butterflies in the Ghetto, which features the stories of the many courageous artists, writers, and musicians who were imprisoned in the Terezin ghetto concentration camp and continued to create.

Read more inspiring stories of survivors of the Holocaust on 10 Amazing Ways People Survived The Holocaust and 10 Inspiring Stories Of True Love From The Holocaust.