The Arts

The Arts  The Arts

The Arts  Crime

Crime 10 Fascinating Facts about Rikers Island

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Things You Might Not Know about Dracula

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Activities That Were Once Considered Illegal

History

History Ten of History’s Hidden Secrets: Stories 99% Don’t Know About

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Who Infamously Stormed Off Set While Filming

Food

Food 10 Foods That Have Alleged Occult Powers

Sport

Sport 10 Lesser-Known Multi-Sport Alternatives to the Olympics

Humans

Humans 10 Real Life Versions of Famous Superheroes

Gaming

Gaming 10 Overused Game Villains

The Arts

The Arts 10 Masterpieces Plucked from the Artist’s Subconscious

Crime

Crime 10 Fascinating Facts about Rikers Island

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Things You Might Not Know about Dracula

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Activities That Were Once Considered Illegal

History

History Ten of History’s Hidden Secrets: Stories 99% Don’t Know About

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Who Infamously Stormed Off Set While Filming

Food

Food 10 Foods That Have Alleged Occult Powers

Sport

Sport 10 Lesser-Known Multi-Sport Alternatives to the Olympics

Humans

Humans 10 Real Life Versions of Famous Superheroes

Gaming

Gaming 10 Overused Game Villains

10 Ancient Facial Reconstructions Of Fascinating Women

Although they’re not always given as much attention as the boys, ancient women do receive their fair share in forensic anthropology. Their stories, told with bone and reanimated flesh, can be as unique as their faces.

It’s amazing how much we can learn from ancient facial reconstructions of women. Whether they are witches, saints, powerful individuals, or forgotten victims, they bring insight into those eras and even give us game-changing clues about history.

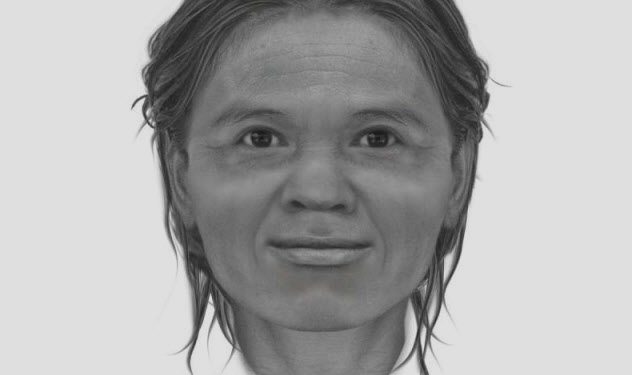

10 The Modern-Looking Ancestor

A pixie-faced person stared back at scientists after a complicated reconstruction process in 2017. At a sprightly 13,000 years old, the finely boned woman’s remains were discovered in the Tham Lod rock shelter in Thailand. In life, she stood 152 centimeters (5′) tall and died at around 25–35 years of age.

To find her features, researchers felt the normal route would not suffice. Most techniques lean toward European looks, which are not truly suitable for somebody who belonged to an ancestral group of modern native Australians and its nearby region of Melanesia.[1]

Instead, measurements were taken from modern females all over the globe. Statistics were compiled on their skulls, skin pigment, and faces. The data from hundreds of women equaled a final head size and skin tone and an average of their features.

The result was then blended with the ancient Thai’s own skull details, teeth, bone, and even facts about her life. This new technique revealed a woman who could pass for a modern person despite being born 13 millennia ago.

9 The Black Market Victim

In the 18th century, a young woman died in Scotland. Her name and life story are unknown, but a stomach-churning narrative is etched in her skull. The woman’s remains were recovered from a plot reserved for the deceased not claimed, usually because the families were too poor to pay for a funeral.

Paupers make for exploitable corpses. During that time, there was a great need for bodies nobody would miss. The Edinburgh Royal Infirmary once stood opposite the cemetery, and the hospital staff moonlighted by selling body parts to the city’s medical underground.

The woman, who was in her late twenties or early thirties, had a cleft skull marking her as one of Edinburgh’s first autopsies. Her front teeth had also been wrenched out.[2] Researchers believe that low-paid workers sold them to the then-thriving market for dentures made with real teeth.

It is not clear why she died. But after death, doctors sawed open her head, likely for research purposes. Edinburgh Royal Infirmary was a flagship in medical research, but the anonymous woman’s treatment highlighted the criminal practices that went with it.

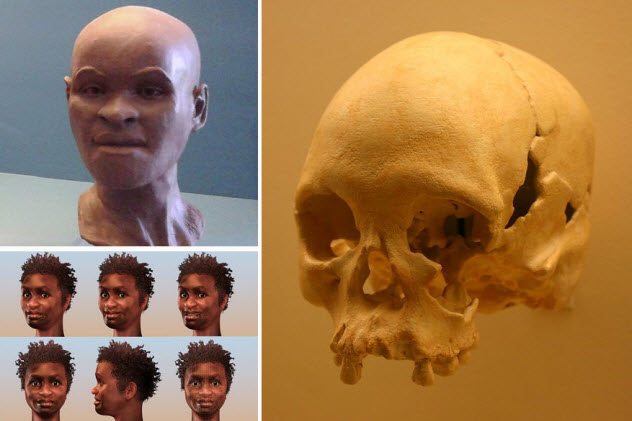

8 Non-Ancestral Americans

Some of the oldest human remains from the Western Hemisphere were forgotten for decades in a museum. They belonged to a woman, nicknamed Luzia, who traveled the Brazilian savanna 11,500 years ago. She is believed to have died in her early twenties.

In 1999, a scientist noticed the unusual skull and had it digitally brought back to life. It was assumed that Luzia would resemble the ancestors of native peoples from North and South America. Previous studies entrenched the theory that these initial Americans migrated from northern Asia.

When Luzia’s cranium was turned into a face, however, she could not have looked more different. Instead of the expected Mongoloid look, her traits were distinctly like the blacks of Africa, Australia, and the South Pacific. This ancient Brazilian could prove that another group, separate from other indigenous people in the Americas, was among the earliest to arrive.

Another 37 other skeletons were found in what could be the oldest American graveyard at nearby Lagoa Santa. These 37 individuals appear to have Luzia’s features and were analyzed in 2005. But there are still competing theories as to where Luzia originated.[3]

7 Senora de Cao

Long before the Incas, the Moche culture flourished in Peru. One of their most iconic mummies is the 1,600-year-old Senora de Cao. Her body was unearthed in 2005 from a tomb on the north coast and was filled with rich goods suggestive of high rank.

She stays in a climate-controlled room which is not visitor friendly. To make her more visible to the public, especially the indigenous community who reveres Senora de Cao, a team gathered to recreate her in 3-D.

First, engineers used handheld scanners and photographed the woman from all angles. Software compiled the images and then stripped the mummified face down to the bone. Forensic experts digitally layered her flesh back together using techniques that help identify murder victims.

To add more soft tissue details, anthropologists gleaned human figures in Moche art, skeletons, photos of northern Peruvians taken a century ago, and the features of living Moche descendants. The head was 3-D printed before artists added clothing as well as skin and eye color.[4]

The result was striking. Instead of a ravished mummy, visitors can now view a high-cheeked woman in her twenties who looks remarkably alive.

6 The Spitalfields Woman

In 1999, archaeologists were excavating a medieval graveyard when they found an enigmatic woman. Located at Spitalfields outside the Roman city of Londinium, her case was as unique as it was unexpected.

An enormous stone sarcophagus contained a lead casket decorated with scallops. At the very heart were the bones, once dressed in gold-embroidered silk. The woman’s affluence and artifacts placed her death at around AD 350. Beyond that, little else was certain.

Two things suggested that she followed an Eastern mystery cult. Several arose during the fourth century, including Christianity. The scallop shell was a Christian symbol, but researchers believe that the woman chose another, somewhat merrier cult.[5]

The second religious connection was a flask. The glass item resembled another found in a French burial, which had contained wine. Around this time, London’s Temple of Mithras belonged to Bacchus, the god of wine.

Analysis of her teeth showed that she was not native to Britain. The theory that she hailed from France or Spain left her facial reconstruction with distinctive dark looks. Dental isotopes eventually revealed the woman as the only verified person from Roman Britain born in Rome.

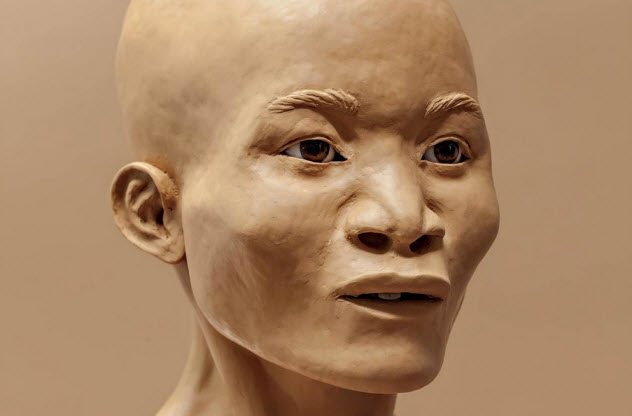

5 The Long-Headed Korean

Several cultures once practiced skull constriction to make their heads appear longer. A woman found in Korea may be the natural exception. While digging at Gyeongju, the capital of the ancient Kingdom of Silla (57 BC–AD 935), something rare was unearthed.

Silla graves with preserved remains are hard to find. In 2013, Gyeongju yielded a coffin with nearly a full skeleton of a woman who died just as she approached her forties. The rarity of her tomb and the fact that her genetic lineage still exists in East Asia were interesting. But the main thing that caught the researchers’ attention was her long head.

Closer investigation and a digital reconstruction proved that the woman did not experience head-binding. Usually, when artificially flattened, the sides of the skull extend and the frontal bones are straighter. As unusual as her head was, the cranial sides and front were normal.[6]

Scientists diagnosed the skull as dolichocephalic, a term used when its width is less than 75 percent of its length. This makes the woman a natural variation of Koreans found in the region today.

4 A Mystery Mummy’s Past

In 2016, the curator at the Harry Brookes Allen Museum worried about a corpse. The Melbourne mummy was a mystery. Apart from a name, Meritamun, the person’s gender, age, and cause of death were unknown.

The request for a scan was over concern about decay, but it unfolded more than just the virtual bandage. The scanned skeleton identified a lady who died very young (18–25). Scientists produced a 3-D printed copy of Meritamun’s skull and brought to life a beautiful Egyptian girl with information gleaned from the scans.

Quality linen reserved for the upper classes wrapped Meritamun, who was likely embalmed around 1500 BC. For her age, she was plagued by several taxing conditions, one of which could have killed her. Thinned and pitted bones meant that she suffered from either anemia or malarial parasites.

Though both serious conditions, researchers believe that Meritamun probably died because of her sweet tooth. She had two dental abscesses that could have resulted from eating honey or sugar. The CT scans showed that the abscesses were serious enough to be considered as a reason for her untimely death.[7]

3 The Brave Witch

Accused of being the Devil’s lover and a witch, an elderly woman stood no chance in 1704. The Scottish villager was tortured until she “confessed.” Sentenced to death, Lilias Adie was determined to protect other women from the same fate.

Enduring horrendous interrogations meant to get names, she claimed that she could not give any because witches at gatherings wore masks. She died in prison, and some believe it was by her own hand. Tradition called for witches to be burned at the stake so that the Devil could not raise the bodies. Most unusually, Lilias was buried along the Fife coast.

During the 20th century, her skull was photographed, and in 2017, forensic scientists wondered if reconstruction was possible using the images as the main source. Lilias’s skull was missing but no longer her appearance.

A mix of forensic techniques, the photographs, and the latest virtual sculpture software revealed one of the many victims persecuted for witchcraft. Far from looking like she was about to nuke the village, Lilias had a grandmotherly face that nobody would fear today.[8]

2 The Oldest American

Luzia from Brazil may be the oldest non-ancestral skeleton from the Americas, but another is related to Native Americans—and even more ancient. The Ice Age teenager, nicknamed Naia, fell to her death in Mexico 12,000 to 13,000 years ago. She remained in the deep underwater pit until 2007 when divers visited the site on the Yucatan Peninsula.

When it comes to historical figures whom one wants to look in the eye, Naia was an obvious choice. Researchers wanted to meet the oldest American. They were surprised when she showed up (as a sculpture).

Genetically, there is no doubt about Naia’s link with later Native Americans. They share a common ancestor from Siberia. But neither resembled the other in the slightest. Her features were unexpected, and Naia’s skull shape was not typically Siberian.

Instead, the structure was more specific to South Pacific or African groups.[9] There is no ready answer to explain why. Some scholars suggest that natural selection changed how Native Americans look over time. But others caution that Naia could merely be a natural variation of the population.

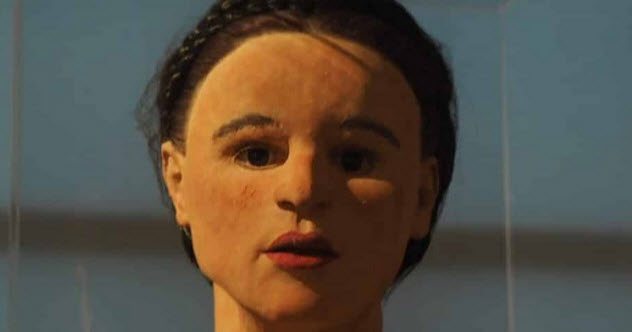

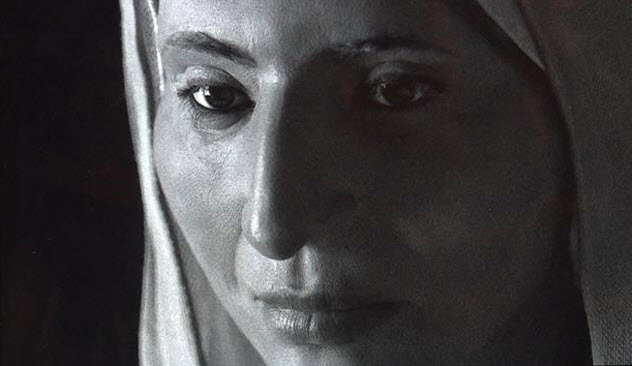

1 The Magdalene Candidate

In the south of France, a basilica has guarded human remains for nearly 2,000 years. Said to be those of Jesus’s female apostle Saint Mary Magdalene, the skull stares out from a display case. (Just to be clear, Mary Magdalene is called the “Apostle to the apostles,” especially by the Roman Catholic Church.)

The holy relic is rather strange. It is black with age, with hair strands still clinging to it, and the skull is embedded in a person-shaped golden bust.[10] The head was last handled in 1974, and recently, scientists received permission to recreate the woman’s face.

The team had to contend with taking hundreds of images as they were not allowed to remove the skull, touch it, or take DNA samples. Applied forensic techniques revealed the possible face of one of the Bible’s most controversial figures.

She was no longer young but still a striking-looking woman in her fifties. The prominent nose, round face with high cheekbones, and brown hair complemented her Mediterranean descent. Similar to unproven tales depicting Mary Magdalene as a prostitute, lead apostle, or Jesus’s wife, it cannot be said with certainty that the skull is really that of the saint.

Read about more fascinating ancient reconstructions on 10 Amazing Facial Reconstructions Of Ancient Skulls and 10 Ancient Reconstructions You Have To See To Believe.