Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Music Biopics That Actually Got It Right

History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

School Shooters On Why They Did It

It’s hard to reconcile the wave of mass shootings that have gripped the world lately. Mass murder is too far outside of what we can understand. For most of us, it’s so inconceivable that it seems inhuman, like something no person with a brain and a body like our own could ever do.

We’re so desperate to understand it that we come up with any kind of explanation that we can wrap our minds around. Perhaps it’s the media’s fault, we think—or bullying, or gun laws, or video games, or TV.

But the murderers haven’t tried to hide why they did. Before nearly every massacre, the shooters have told us exactly what they were thinking. They’ve written manifestos that let us see what’s happening inside their broken minds. They’ve spelled out the twisted logic that brought them to kill.

They’ve given us their answers, in their own twisted way. But be warned: These are the thoughts of deranged minds, and the answers are never as simple as we want them to be.

10 Elliot Rodger

“I will have my revenge against humanity,” 22-year-old Elliot Rodger promised in a video uploaded to YouTube in 2014, shortly before he walked into a UC Santa Barbara sorority house and slaughtered six people before killing himself.

“I’m 22 years old and still a virgin,” Rodger complained. “I’ve had to rot in loneliness. It’s not fair.” His massacre, he said, was something the world deserved “just for the crime of living a better life than me.”

For all his complaining, though, Rodger didn’t exactly have a low self-esteem. He called himself “the perfect guy” and “the supreme gentleman,” promising that after he’d killed, they would see that he was “the true alpha male.” He had a delusion that was “a god” compared to the rest of humanity, and after the massacre, he believed, the world would see him the way he saw himself.

His agony didn’t just come from self-hatred. He had delusions of grandeur, and when the world didn’t reciprocate his narcissism, he saw it as their fault, not his. Women, he declared, should not have “the right to choose who to mate and breed with”—because by not choosing him, they’d shown they couldn’t make the right choice.

In a massive 141-page manifesto, he detailed his vision of an “ideal world”: one where women had no rights and the human sex drive was obliterated.[1] “If I cannot have it,” Rodger warned, “I will do everything I can to destroy it.”

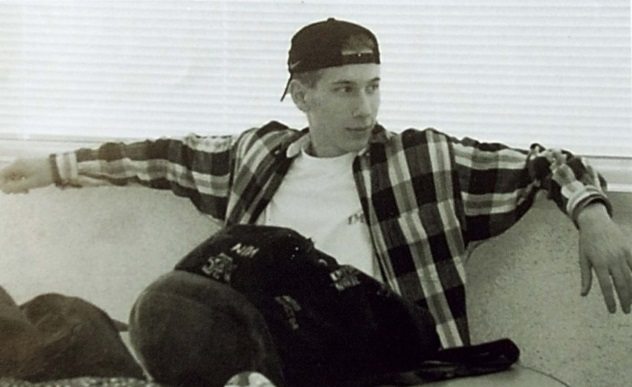

9 Eric Harris

“Someone’s bound to say, ‘What were they thinking?’ ” Eric Harris wrote in his journal, days before he and his friend Dylan Klebold walked into Columbine High School and killed 13 people. “This is what I’m thinking. I have a goal to destroy as much as possible.”[2]

Harris saw himself as an enlightened person because he saw the irrelevance of life. “People will say things like, ‘Oh, it was so tragic,’ ” he predicted. “You think that’s a bad thing? Just because your mommy and daddy told you blood and violence is bad, you think it’s a f—ing law of nature?”

He saw his massacre as an act of natural selection. “Everyone should be put to a test,” he wrote, “see who can survive in an environment using only smarts and military skills.” Those who didn’t question conventional values, he felt, were “unfit for anything at all. Especially life.”

His journals, the FBI believes, reveal a “messianic-grade superiority complex.” He saw himself as above humanity, like an angel of death sent to decide who deserved to live and die.

Harris deemed few worthy to live. “The majority of the audience won’t even understand my motives,” he wrote. “They’ll say, ‘Ah, he’s crazy, he’s insane, oh well, I wonder if the Bulls won.’ ”

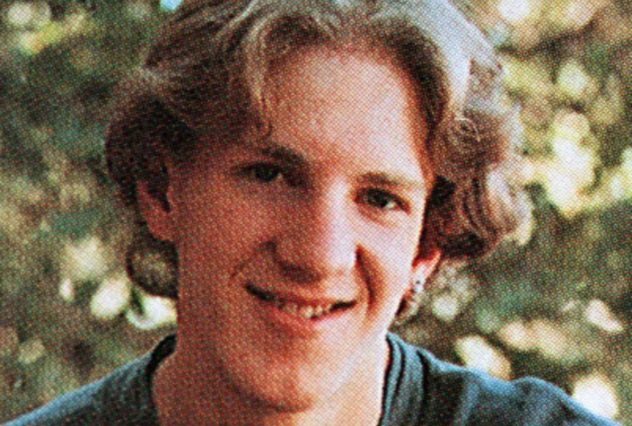

8 Dylan Klebold

While Harris filled his journal with furious condemnations of humanity, Dylan Klebold’s journal was full of poems and a deep longing for some type of human connection.

“The world is the greatest punishment: life,” Klebold wrote in his journal. He’d been cutting himself to kill the pain that he blamed on his inability to get a steady girlfriend. To Klebold, love was the only path to a meaningful life. In a short poem, he wrote, “The true great person achieves happiness only when he has met his soulmate.”

For all he craved human connection, though, Klebold didn’t see himself as human. He mused in his diary about when he “got covered up by this entity” that had taken over his body. In other entries, he called himself “a non-human” or a “god.” He was, he believed, “the God of Sadness.”[3]

He and Harris, Klebold said, were “conceived from ourselves and each other.” The rest of humanity were “zombies,” sent as “a test to see if our love was genuine.”

“Time to die, time to be free,” Klebold wrote, days before the massacre. “Time to love.”

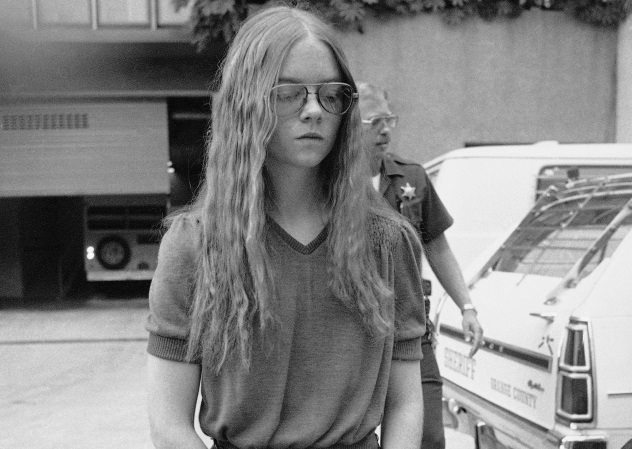

7 Brenda Spencer

“I don’t like Mondays.”

That was the only explanation 16-year-old Brenda Spencer gave. In 1979, she set up a rifle in her San Diego home and opened fire on the elementary school across the street, wounding eight children and an officer and killing two adults. When a reporter asked why, though, all she said was that she didn’t like Mondays and that she was bored. “This livens up the day.”

The callous and total lack of remorse in her answer made the phrase a cultural phenomenon, and what little else she said during the attack didn’t help anyone understand. When she surrendered to police, she told them that shooting children was “like shooting ducks on a pond” and that she “liked to watch them squirm after they were hit.”[4]

But despite the detached face Spencer wore throughout her actions, the things she said before she started shooting seem to hint that there was more that led her to that moment than just boredom. The gun she’d used had been given to her by her father, and she’d taken it as a hint. “I asked for a radio and he bought me a gun,” Spencer said. “I felt like he wanted me to kill myself.”

Spencer, who had described fantasies of becoming a sniper to her friends and family, told her friends she was going to use the gift for something else. Before she started shooting, she told her friends she had a different motive. Watch the news, she told them—because she was going to “do something big to get on TV.”

6 Evan Ramsey

“What I wanted,” Evan Ramsey told a reporter, years after walking into Bethel Regional High School in Alaksa in 1997 and shooting two of his classmates with a 12-gauge shotgun, “was to get people to leave me alone.”[5]

Ramsey spent most of his childhood moving through foster homes, most of which were, in his words, “fairly abusive.” His mother had been a binge drinker, and his first foster father had beaten him with a bungee cord.

It took years before he moved in with a mother who took good care of him. Still, Ramsey struggled with bullying at school, and after telling his foster mother about it, he decided to do something about it. She told him to “do the mature and adult thing and report all incidents of bullying to the principal,” Ramsey told a reporter, before shrugging and adding, “Didn’t seem to work.”

“I decided I needed to do something to stand up for myself,” Ramsey said. “I chose to kill.”

5 Caleb Sharpe

“I always knew you were going to shoot up the school,” Sam Strahan, one of Caleb Sharpe’s classmates, said in 2017 when he saw 15-year-old Sharpe walk into Freeman High School in Rockford, Washington, with a semiautomatic rifle. It was the last thing Strahan would say before Sharpe murdered him and injured three other students.

Sharpe told police he’d killed Strahan “to teach everyone a lesson about what happens when you bully others.” Before his massacre, he’d written “kill” on photographs of 26 students in his yearbook who he’d planned on targeting.

The people who know him, though, aren’t convinced. “We knew for a fact he wasn’t being bullied,” one of Sharpe’s classmates said. Instead, Sharpe’s problem was mental illness. He’d already been seeing a school counselor about his dangerous thoughts, and he’d passed around notes warning that he was planning on hurting people. Sam Strahan wasn’t the only one who saw this coming.

Some of the things Sharpe wrote in his notebooks before the massacre reveal the depths of his madness. Like Dylan Klebold, he wrote some of his notes as if he were another entity living in a young boy’s body.

“I am the one who deserved to live, but I still need Caleb until I kill all those . . . kids,” Caleb wrote, apparently imagining he was possessed by something else. “Then Caleb will finally die while I live on.”[6]

4 Luke Woodham

“October 1, 1997, will go down in history as the day I fought back,” 16-year-old Luke Woodham wrote before murdering his mother with a butcher’s knife and opening fire inside of Pearl High School in Mississippi. “I kill because people like me are mistreated every day. I do this to show society—push us and we will push back.”

He’d spent his life being teased by classmates and taunted by his mother, he claimed, and was tired of “watching Johnny football player get the glory.” He’d started moving into different circles, joining a clique of self-proclaimed Satanists who encouraged his violent tendencies and, according to Woodham, helped him plan the massacre. To get ready to kill, Woodham crushed his dog’s head in and set it on fire.

It’s hard to say, though, how much of what Woodham says is true. According to the police, Luke had “psychotic processing” and “misinterpreted reality.” He claimed his friend Grant Boyette had pushed him into killing, but he also said that he’d “seen demons” that encouraged him to kill.

“He told me I had to kill my mom,” Woodham told the police. Woodham didn’t object. His mother, he claimed, was one of the people who had “mistreated” him. “She never loved me. Always told me I wouldn’t amount to anything, that I was fat and lazy.”

Moments later, though, Woodham broke down into tears and told a completely different story. “I loved my mother,” he said. “I know she forgives me.”[7]

3 Elizabeth Bush

“There was a deep part of me that just exploded,” eighth-grader Elizabeth Bush said after she walked into her school cafeteria in 2001 and shot her closest friend, Kimberly Marchese. “I’m not normally like that.”

Bush claimed she’d been bullied by her classmates at Bishop Neuman Junior-Senior High School in Pennsylvania. “They’d just call me an idiot, stupid, fat, ugly, whatever,” she said. “One incident was I was walking home from school and five or six kids were behind me and they started throwing stones at me . . . They were just kind of laughing and I don’t know why they were doing this but they were barking at me.”

In a fit of depression, Bush started cutting herself. It was a secret she only revealed to Kimberly Marchese. Soon, though, Bush was overcome with a paranoid sense that Marchese had told others. She swore revenge, saying, “I wanted her to know my pain.”[8]

But Marchese, who survived the attack, thinks everything Bush described was happening in her head. Bush, she said, “wasn’t in the best health mentally.” She had told Marchese that she was “able to talk to God.”

Despite the fight Bush had imagined, Marchese insisted after the shooting, “I haven’t talked to Elizabeth Bush for about a week or two, and there was no argument before the shooting whatsoever.”

This, to Marchese, was just another one of her friend’s outbursts. “I know she sometimes says stuff and then she’ll regret it,” Marchese has said. “I think that’s just what happened to her at the shooting.”

2 Jaylen Fryberg

“I needed to do this,” Jaylen Fryberg wrote in 2014 in his final text message to his family.[9] Moments later, he would walk into his Marysville, Washington, school, kill four of his classmates, and commit suicide.

He asked his family to apologize to his friends’ parents for what he was about to do, saying he needed his “crew” to come with him. “I needed [my] ride or dies with me on the other side.”

A breakup set him off. Days before the massacre, Fryberg’s girlfriend broke up with him. In retaliation, he started bombarding her with texts promising he’d kill himself and trying to blame her for it. “Don’t bother coming to my funeral,” Fryberg texted her. “I set the date. Hopefully you regret not talking to me.”

In his final message, he told his parents that he loved them but that he “wasn’t happy.” To him, his massacre was nothing more than a trip to the other side of existence. He just wanted to make sure his friends were there with him. He murdered four people and injured one more purely because, in his words, “I didn’t want to go alone.”

1 Cho Seung-Hui

“You caused me to do this,” Cho Seung-Hui said in a manifesto he sent to MSNBC on the day of the Virginia Tech Massacre. He was getting ready for a slaughter that would kill 32 people and injure 23 more. It would be one of the worst school shootings in history.

“Oh the happiness I could have had mingling among you hedonists, being counted as one of you,” Cho wrote in his rambling, borderline nonsensical manifesto, “if only you didn’t f— the living sh— out of me.”[10]

He accused society of “raping my soul” and “committing emotional sodomy,” although he never quite explained what that meant. In part, though, he was furious at people he called “Descendants of Satan Disguised as Devout Christians.”

He saw himself as the Messiah. “Like Moses, I spread the sea and lead my people [ . . . ] to eternal freedom,” he said. He called Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold “martyrs,” people who had sacrificed their lives to make society suffer, and chillingly promised that his massacre would “set the example of the century for my Children to follow.”

For all his God complex, though, the people who knew Cho saw him as pitiful. A teacher called him the “loneliest person I have ever met in my life.” In the work he’d handed in, there might have been a clue into what made him this way. He’d written play after play, all about the same thing: young boys being abused by pedophiles.

Read more statements from infamous criminals on 10 Serial Killers On Why They Did It, In Their Own Words and 10 Chilling Manifestos From Killers.