Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Top 10 Great Accomplishments Made During Quarantine

The year is far from over, but you should probably put money on “social distancing” being the most popular phrase of 2020. This is the year of COVID-19, a worldwide pandemic that has infected 242,191 people worldwide and claimed 9,843 lives as of this writing.

The coronavirus has forced governments to cancel mass gatherings, classes in schools, sporting events, and much more to halt the spread of the novel virus. Billions of everyday people are now learning to love being in quarantine.

If this applies to you, then cheer up. Some of the greatest artists and inventors have managed to change the world for the better from their quarantined rooms. Let this list serve as a reminder to read more, sleep more, and create more during your enforced isolation.

10 Quarantine Islands and Lazarettos

10 Eugene Onegin

Alexander Pushkin’s standing in Russia is equivalent to William Shakespeare’s in Great Britain. Pushkin is the “great bard” of Russian letters, and one of his greatest productions is the verse novel Eugene Onegin (1832).

The story focuses on the life of Eugene Onegin, a wealthy and spoiled aristocrat living in Saint Petersburg. When Onegin becomes tired of attending all the city’s balls and dances, he decides to move to his deceased uncle’s country estate.

There, he meets the poet Vladimir Lensky. Onegin also meets the beautiful Tatyana Larina, who becomes his lifelong obsession. In 1879, Eugene Onegin was turned into an opera by the great Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Pushkin, himself a dandy like Eugene Onegin, often turned to writing whenever he was sick (most often with some form of venereal disease). In fall 1830, a terrible cholera outbreak in Moscow convinced Pushkin to leave for his family’s estate in the country. There, while doing a little social distancing, Pushkin completed Eugene Onegin and other classic works.[1]

9 Samuel Pepys’s Diary

Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) was a Member of Parliament and a civil administrator for the English Navy. During his life, he was best known for his efforts to modernize the navy and its administration. Nowadays, Pepys is best known for the diary that he kept from 1660 until 1669, which remains one of the best primary documents concerning the English Restoration.

In 1665, the bubonic plague struck London. Unlike most fellow Londoners, Pepys was not surprised by the outbreak because he had seen a similar outbreak of the “black death” in Amsterdam two years earlier. In June 1665, Pepys wrote, “[To] my great trouble, hear that the plague is come into the City.” Then he added, “God preserve us all.”[2]

Thanks to Pepys’s active pen, historians and scientists have a good understanding of how the bubonic plague moved so quickly and proved so devastating in London. Essentially, a massive rat population in the filthy city spread the plague.

8 Alexander The False Prophet

Lucian was one of the great wits of the Roman Empire. An Assyrian born in the imperial city of Samosata (located today in southern Turkey), Lucian was a popular playwright, satirist, and rhetorician. His works mocked such things as the differences between Greeks and Syrians, stoicism, and cults. One of his more important works, Alexander the False Prophet, lampooned magic and those Romans who sought supernatural explanations for life’s miseries.

The “Alexander” of the title was a real person named Alexander of Abonoteichus. Like Lucian, Alexander came from Asia Minor. Not too much is known about Alexander except that he claimed to be a powerful magician who could cure the sick.

This claim caught on with Roman citizens and imperial subjects because a massive plague started in AD 165. Called the Antonine Plague, it cut a swath through the Roman Empire.[3]

First discovered by the brilliant Greek physician Galen, the plague most likely came from China and was spread via the Silk Road. Today, the plague is thought to have been either measles or smallpox.

While the Romans isolated themselves or sought magical cures, Lucian decided to write a satire of a fake spiritual healer.

7 The Magic Mountain

Considered one of the finest works in all of German literature, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain was first published in 1924. The novel concerns Hans Castorp, a young Hamburg merchant who decides to visit his cousin Joachim at a tuberculosis sanatorium in the Swiss Alps.

Hans’s simple journey soon becomes complicated as his health fails and he begins to meet other patients. Almost all of them represent the social decay of Europe after World War I.

Mann knew a thing or two about sanatoriums. His wife, Katia, suffered from tuberculosis, and in 1912, she stayed at a sanatorium in Davos-Platz, Switzerland. Mann visited her often. In the following years, the two were regular patients at health spas throughout the world. Mann turned this experience into the setting for The Magic Mountain.[4]

6 Dashiell Hammett

American writer Dashiell Hammett was born to raise hell. The son of an old Catholic farming family in Maryland, Sam “Dashiell” Hammett dropped out of school at 13 and began hanging out with gamblers, prostitutes, and thieves in Baltimore and Philadelphia.

In an attempt to turn his life around, Hammett signed up with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in 1915. He worked as a private eye until 1922. A few years later, Hammett started writing detective fiction. Without question, he used his real-life experiences to create the fictional private eyes Sam Spade and the Continental Op.[5]

Hammett might never have become a writer if he hadn’t contracted tuberculosis while serving in the US Army during World War I. The army recorded that Hammett was 25-percent disabled because of the disease and granted him a medical discharge. The army also gave Sergeant Hammett a small pension.

Thanks to this pension and a part-time job as a copywriter, Hammett had time to devote to writing, which was still frequently interrupted by his terrible coughing fits.

10 Horrors Of The Great Plague Of London

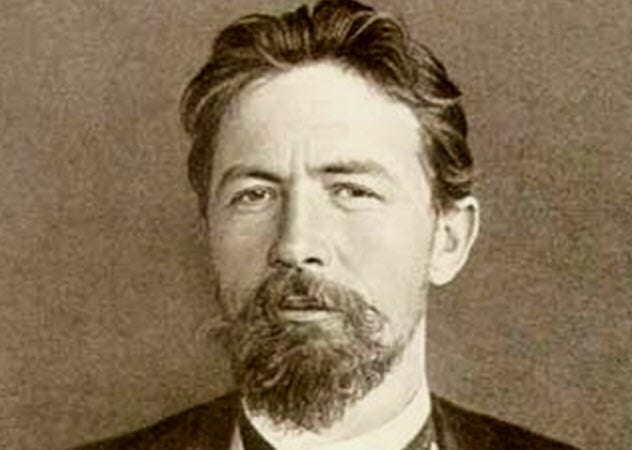

5 Anton Chekhov

Like Pushkin before him, Russian writer Anton Chekhov found time to write due to Russia’s frequent cholera epidemics. Between 1892 and 1899, Chekhov wrote some of his best-known short stories, including “Ward No. 6” and “The Black Monk.”

At the same time, Chekhov lived a semi-isolated life at his Melikhovo estate. It was here that Chekhov helped to organize famine and cholera relief for the local peasants. He also continued his day job as a practicing doctor.

Sadly, Chekhov had to stop practicing medicine in 1897 due to his worsening health. Like Hammett, Chekhov suffered from tuberculosis. The disease killed him in 1904.[6]

Today, Chekhov is hailed as one of the world’s greatest short story writers. Many of these short stories came as a result of what Chekhov saw as a doctor during the cholera epidemics of the late 19th century.

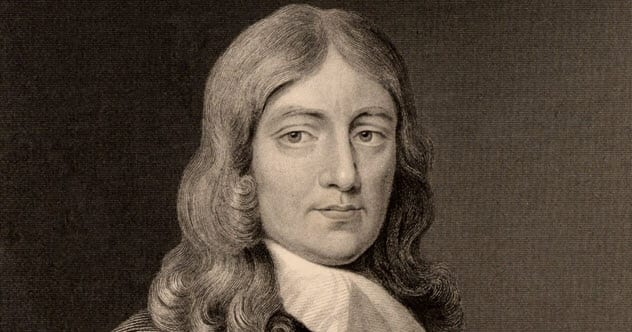

4 Paradise Lost

The Englishman John Milton was many things during his life—a pamphleteer, a philosopher, and a politician who served as the Secretary of Foreign Tongues (Latin Secretary) for England’s Commonwealth Council of State. Milton is best known today as a poet, specifically the one who wrote the epic Paradise Lost about Satan’s fall from grace and his war against God, Heaven, and humanity.

Many know that Milton went blind while composing Paradise Lost. Between 1652 and 1667, Milton had to dictate his epic poem to his family members, friends, and amanuenses. This process was made more difficult when the Milton family had to move to a new home at Chalfont St. Giles to avoid the Great Plague of London in 1665–66. It was here that Milton finished Paradise Lost.[7]

3 The Decameron

The Decameron is arguably the greatest piece of literature about a pandemic. Most likely written between 1348 and 1353, The Decameron is about 10 young aristocrats who flee to a country estate to avoid the Black Death in Florence. Inside the estate, the aristocrats tell 100 stories over several days.

Most of the stories are somber, although some are funny and full of practical jokes. The Decameron, much like Dante’s Divine Comedy, is written in the Florentine vernacular, which eventually became standard Italian.

Giovanni Boccaccio, the man who wrote The Decameron, lived through the terrible plague years of the 14th century. Like the characters in his most famous work, Boccaccio successfully avoided the plague in Florence by traveling to Naples and other Italian cities. However, he did witness the Florentine plague firsthand in 1348.[8]

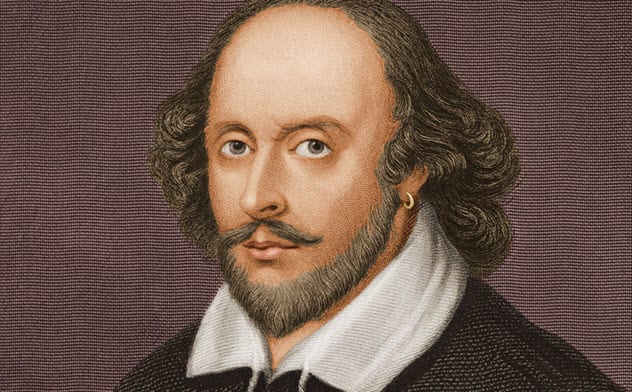

2 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare’s entire life was full of plague epidemics. In fact, the infant Shakespeare was one of the few residents in Stratford-upon-Avon to survive the plague of 1564. One of Shakespeare’s most prominent biographers, Jonathan Bate, has written that Shakespeare’s experience with the plague was the single most defining aspect of his life and work.

The plague appears in several of Shakespeare’s best works, including Romeo and Juliet. Even more startling, Shakespeare’s greatest burst of energy occurred between 1605 and 1606 when he composed King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra.

Scholars now believe that Shakespeare was so productive during this time because 1605–06 was a plague year in England. Rather than brood while in quarantine, Shakespeare decided to write.[9]

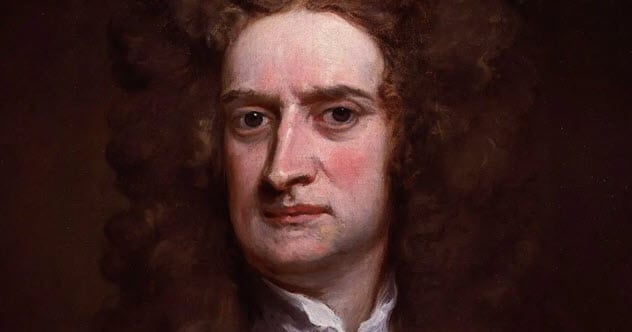

1 Isaac Newton

The English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton is regarded as the man who discovered gravity and, in turn, wrote down the laws of physics. Without Newton’s discoveries, the Age of Enlightenment may never have happened.

In 1665, Newton was a subpar student at Cambridge University. That year, the university closed due to the Great Plague of London. With school closed, Newton returned to his family’s home in Cambridge and began conducting a series of experiments.

While working during quarantine, he first began observing the laws of motion and gravity. When Newton returned to Cambridge University in 1667, he bolted up the university ranks from undergraduate to fellow and then professor in 1669.[10]

Top 10 Things You Need To Do To Prepare For The Coronavirus

About The Author: Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in New England.