Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Top 10 Greatest Philosophers in History

This list examines the influence, depth of insight, and wide-reaching interest across many subjects of various “lovers of wisdom” and ranks them accordingly. It should be noted, first and foremost, that philosophy in its traditional sense was science. Philosophers (like Aristotle) used rationality to come to scientific knowledge of the world around us. It was not until relatively modern times that philosophy was considered to be separate from the physical sciences.

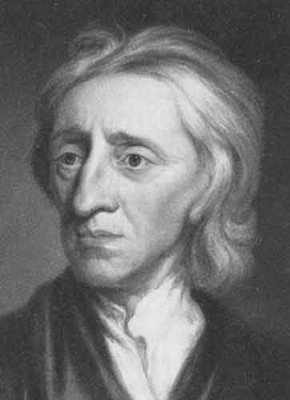

10 John Locke

The most important thinker of modern politics is the one most directly responsible for Thomas Jefferson’s rhetoric in “The Declaration of Independence” and the rhetoric in the U.S. Constitution. Locke is referred to as the “Father of Liberalism” because of his development of the principles of humanism and individual freedom, founded primarily by #1. It is said that liberalism proper, the belief in equal rights under the law, begins with Locke. He penned the phrase “government with the consent of the governed.” His three “natural rights,” that is, rights innate to all human beings, were and remain “life, liberty, and estate.”

He disapproved of the European idea of nobility enabling some to acquire land through lineage while the poor remained poor. Locke is the man responsible, through Jefferson primarily, for the absence of nobility in America. Although nobility and birthrights still exist in Europe, especially among the few kings and queens left, the practice has all but vanished. The true democratic ideal did not arrive in the modern world until Locke’s liberal theory was taken up.[1]

Take a new stance on philosophy with The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times And Ideas Of The Great Economic Thinkers at Amazon.com!

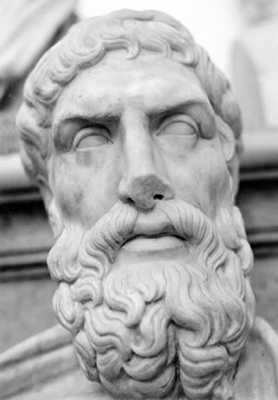

9 Epicurus

Epicurus has gotten a bit of an unfair reputation over the centuries as a teacher of self-indulgence and excess delight. He was soundly criticized by many Christian polemicists (those who make war against all thought but Christian thought). This occurred especially during the Middle Ages because he was thought to be an atheist, whose principles for a happy life were passed down through his famous set of statements: “Don’t fear god; don’t worry about death; what is good is easy to get; what is terrible is easy to endure.”

He advocated the principle of refusing belief in anything that was not tangible, including any god. Such intangible things he considered preconceived notions, which could be manipulated. You may think of Epicureanism as “no matter what happens, enjoy life because you only get one and it doesn’t last long.” Epicurus’s idea of living happily centered on the just treatment of others, avoidance of pain, and living in such a way as to please oneself, but not to overindulge in anything.

He also advocated a version of the Golden Rule, “It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly (agreeing ‘neither to harm nor be harmed’), and it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living a pleasant life. “Wisely,” at least for Epicurus, would be avoidance of pain, danger, disease, etc.; “well” would be proper diet and exercise; and “justly,” in the Golden Rule’s sense of not harming others because you do not want to be harmed.[2]

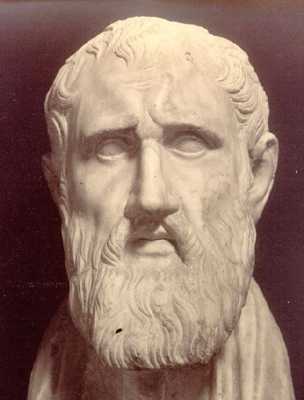

8 Zeno of Citium

You may not be as familiar with him as most others on this list, but Zeno founded the school of Stoicism. Stoicism comes from the Greek “stoa,” which is a roofed colonnade, especially that of the Poikile, which was a cloistered piazza on the north side of the Athenian marketplace in the 3rd Century BC. Stoicism is based on the idea that anything which causes us to suffer in life is actually an error in our judgment and that we should always have absolute control over our emotions. Rage, elation, and depression are all simple flaws in a person’s reason, and thus, we are only emotionally weak when we allow ourselves to be. Put another way, the world is what we make of it.

Epicureanism is the usual school of thought considered the opposite of Stoicism, but today many people mistake one for the other or combine them. Epicureanism argues that displeasures exist in life and must be avoided to enter a state of perfect mental peace (ataraxia, in Greek). Stoicism argues that mental peace must be acquired out of your own will not to let anything upset you. Death is a necessity, so why feel depressed when someone dies? Depression doesn’t help. It only hurts. Why get enraged over something? The rage will not result in anything good. And so, in controlling one’s emotions, a state of mental peace is brought about. Of importance is to shun desire: you may strive for what you need, but only that and nothing more. What you want will lead to excess, and excess doesn’t help but hurts.[3]

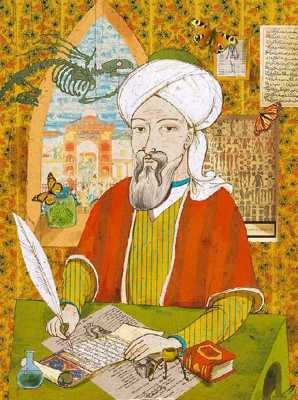

7 Avicenna

His full name is Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā, the last two words of which were Latinized into the more common form in Western history. He lived in the Persian Empire from c. 980 to 1037. The Dark Ages were not so dark. Aside from his stature as a philosopher, he was also the world’s preeminent physician during his life. His two most well-known works today are The Book of Healing (which has nothing to do with physical medicine) and The Canon of Medicine, which was his compilation of all known medical knowledge at that time.

Influenced primarily by #1, his Book of Healing deals with everything from logic, math, music, and science. He proposed in it that Venus is closer than the Sun to Earth. Imagine not knowing that for a fact. The Sun looks a lot closer than Venus, but he got it right. He rejected astrology as true science since everything in it is based on conjecture, not evidence. He theorized that some fluid deep underground was responsible for the fossilization of bone and wood, arguing that “a powerful mineralizing and petrifying virtue which arises in certain stony spots or emanates suddenly from the earth during earthquake and subsidences…petrifies whatever comes into contact with it. As a matter of fact, the petrifaction of the bodies of plants and animals is not more extraordinary than the transformation of waters.”

This is not correct, but it’s closer than you might believe. Petrifaction can occur in any organic material and involves the material, most notably wood, being impregnated by silica deposits, gradually changing from its original materials into stone. Avicenna is the first to describe the five classical senses: taste, touch, vision, hearing, and smell. He may have been the world’s first systematic psychologist in a time when people suffering from a mental disorder were said to be possessed by demons. Avicenna argued that there were somatic possibilities for recovery inherent in all aspects of a person’s body, including the brain.

John Stuart Mill’s five methods for inductive logic stem mostly from Avicenna, who first expounded on three of them: agreement, difference, and concomitant variation. It would take too long to explain them in this list, but they are all forms of syllogisms, and every philosopher and student of philosophy is familiar with them from the beginning of their education in the subject. They are critical to the scientific method, and whenever someone forms a statement as a syllogism, they are using at least one of these methods.[4]

6 Thomas Aquinas

Aquinas will forever be remembered as the guy who supposedly proved the existence of God by arguing that the Universe had to have been created by something since everything in existence has a beginning and an end. This is now referred to as the “First Cause” argument, and all philosophers after Aquinas have wrestled with proving or disproving the theory. He actually based it on the notion of “ού κινούμενον κινεῖ,” by #1. The Greek means “one who moves while not moving” or “the unmoved mover.”

Aquinas founded everything he postulated firmly in Christianity, and for this reason, he is not universally popular today. Even Christians consider that, since he derived all his ethical teachings from the Bible, he is not independently authoritative of any of those teachings. But his job, in teaching the common people around him, was to get them to understand ethics without all the abstract philosophy. He expounded on #2’s principles of what we now call “cardinal virtues”: justice, courage, prudence, and temperance. He was able to reach the masses with this simple, four-part instruction.

He made five famous arguments for the existence of God, which are still discussed hotly on both sides: theist and atheist. Of those five, which he intended to define the nature of God, one is called “the unity of God,” which is to say that God is not divisible. He has essence and existence, and these two qualities cannot be separated. Thus, if we can express something as possessing two or more qualities, and cannot separate the qualities, then the statement itself proves that there is a God, and Aquinas’s example is the statement, “God exists,” in which statement subject and predicate are identical.[5]

5 Confucius

Master Kong Qiu, as his name translates from Chinese, lived from 551 to 479 BC and remains the most important single philosopher in Eastern history. He espoused significant principles of ethics and politics in a time when the Greeks were espousing the same things. We think of democracy as a Greek invention, a Western idea, but Confucius wrote in his Analects that “the best government is one that rules through ‘rites’ and the people’s natural morality, rather than by using bribery and coercion.” This may sound obvious to us today, but he wrote it in the early 500s to late 400s BC. It is the same principle of democracy that the Greeks argued for and developed: the people’s morality is in charge, therefore, rule by the people.

Confucius defended the idea of an Emperor but also advocated limitations to the emperor’s power. The emperor must be honest, and his subjects must respect him, but he must also deserve that respect. If he makes a mistake, his subjects must offer suggestions to correct him, and he must consider them. Any ruler who acted contrary to these principles was a tyrant and thus a thief more than a ruler.

Confucius also devised his own, independent version of the Golden Rule, which had existed for at least a century in Greece before him. His phrasing was almost identical but then furthered the idea: “What one does not wish for oneself, one ought not to do to anyone else; what one recognizes as desirable for oneself, one ought to be willing to grant to others.” The first statement is in the negative and constitutes a passive desire not to harm others. The second statement is much more important, constituting an active desire to help others. The only other philosopher of antiquity to advocate the Golden Rule in the positive form is Jesus of Nazareth.[6]

Smart is the new sexy! Show off your brilliance with this awesome I Heart Confucius T-Shirt at Amazon.com!

4 Rene Descartes

Descartes lived from 1596 to 1650, and today he is referred to as the “Father of Modern Philosophy.” He created analytical geometry, based on his now immortal Cartesian coordinate system, immortal in the sense that we are all taught it in school and that it is still perfectly up-to-date in almost all branches of mathematics. Analytical geometry is the study of geometry using algebra and the Cartesian coordinate system. He discovered the laws of refraction and reflection. He also invented the superscript notation still used today to indicate the powers of exponents.

He advocated dualism, which is basically defined as the power of the mind over the body: strength is derived by ignoring the weaknesses of the human physique and relying on the infinite power of the human mind. Descartes’s most famous statement, now practically the motto of existentialism: “Je pense donc je suis;” “Cogito, ergo sum;” or “I think, therefore I am.” This is not meant to prove the existence of one’s body. Quite the opposite, it is meant to prove the existence of one’s mind. He rejected perception as unreliable and considered deduction the only reliable method for examining, proving, and disproving anything.

He also adhered to the Ontological Argument for the Existence of a Christian God, stating that, because God is benevolent, Descartes can have some faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, for God has provided him with a working mind and sensory system and does not desire to deceive him. From this supposition, however, Descartes finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. In terms of the study of knowledge, therefore, he can be said to have contributed such ideas as a rigorous conception of foundationalism (basic beliefs) and the possibility that reason is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge.[7]

3 Augustine of Hippo

Aurelius Augustinus (St. Augustine) lived in the Roman Empire from AD 354 to 430. In 386, he converted to Christianity. He was a teacher of rhetoric and became the Bishop of the city of Hippo. His Confessions, The City of God, and Enchiridion are among the most influential works of Western thought. Augustine’s work in metaphysics, ethics, and politics remains important today. Key among these accomplishments are his metaphysical analysis of time, his ethical analysis of evil, and his examination of the conditions for justified war.

Augustine’s most profound impact, however, comes from his interpretation of Christianity. In AD 400, Christianity was barely four centuries old, far younger than some competing religions, and not unified in its own doctrine. Augustine produced a sophisticated interpretation of Christian thinking by merging it with the philosophy of Plato and Neoplatonism. With this merger of ideas, Christianity takes on the idea of God as an independent, immaterial reality—the transcendent God. This idea of God is so familiar to many of us now that it may seem odd to think of God in any other way. Still, it was Augustine’s appropriation of Plato’s two-level view of reality that produced the mysterious non-material God who exists outside of all space and time (e.g., is infinite and eternal).

Indeed, other people, including Christians, had expressed such metaphysical conceptions of God before, but Augustine brought to Christianity an intellectual account and body of reasoned arguments to ground these ideas. The overarching point here is that Augustine applied philosophical analysis and reasoning to the issues of religion. Mere belief without questioning and truth-seeking were not sufficient for genuine faith. For him, believing and understanding were interrelated states of mind.[8]

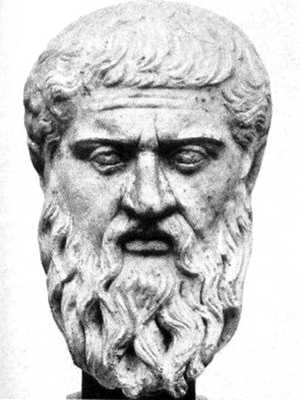

2 Plato

Plato lived from c. 428 to c. 348 BC and founded the Western world’s first school of higher education, the Academy of Athens. Almost all of Western philosophy can be traced back to Plato, who was taught by Socrates and preserved through his own writings some of Socrates’s ideas. If Socrates wrote anything down, it has not survived directly. Plato and Xenophon, another of his students, recounted many of his teachings, as did the playwright Aristophanes.

One of Plato’s most famous quotations concerns politics, “Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils…nor, I think, will the human race.” He means that any person(s) in control of a nation, city, or city-state must be wise and, if they are not, they are ineffectual rulers. It is only through philosophy that the world can be free of evils. Plato’s preferred government was one of benevolent aristocrats, those born of nobility, who are well educated and good, who help the common people to live better lives. He argued against democracy’s proper rule by the people themselves since, in his view, a democracy had murdered his teacher, Socrates.

If not his political theories, Plato’s most enduring theory is that of “The Forms.” Plato wrote about these forms throughout many of his works and asserted, through them, that immaterial abstractions possess the highest, most fundamental kind of reality. All things of the material world can change, and our perception of them also means that the reality of the material world is weaker, less defined than that of the immaterial abstractions. Plato argued that something must have created the Universe. Whatever it is, the Universe is its offspring, and we, living on Earth, our bodies and everything that we see and hear and touch around us, are less real than the creator of the Universe and the Universe itself. This is a foundation on which #4 based his understanding of existentialism.[9]

1 Aristotle

Aristotle topped another of this lister’s lists, heading the category of philosophy, so his rank on this one is not entirely surprising. But consider that Aristotle is the first to have written systems to understand and criticize everything from pure logic to ethics, politics, literature, even science. He theorized that there are four “causes,” or qualities, of anything in existence: the material cause, which is what the subject is made of; the formal cause, or the arrangement of the subject’s material; the effective cause, the creator of the thing; and the final cause, which is the purpose for which a subject exists.

That all may sound perfectly obvious and not worth arguing over, but since it would take far too long for a top ten list to expound on classical causality, suffice to say that all philosophers since Aristotle have had something to say on the matter, and absolutely everything that has been said, and perhaps can be said, is, or must be, based on Aristotle’s system of it: it is impossible to discuss causality without using or trying to debunk Aristotle’s ideas.

Aristotle is also the first person in Western history to argue that there is a hierarchy to all life in the Universe; that because Nature never did anything unnecessary as he observed, then, in the same way, this animal is in charge of that animal, and likewise with plants and animals together. His so-called “ladder of life” has eleven rungs, at the top of which are humans. The Medieval Christian theorists ran with this idea, extrapolating it to the hierarchy of God with Man, including angels. Thus, the angelic hierarchy of Catholicism, usually thought of as a purely Catholic notion, stems from Aristotle, who lived and died before Jesus was born. Aristotle was, in fact, at the very heart of the classical education system used through the Medieval western world.[10]

Aristotle had something to say on just about every subject, whether abstract or concrete, and modern philosophy almost always bases every single principle, idea, notion, or “discovery” on the teaching of Aristotle. His principles of ethics were founded on the concept of doing good rather than merely being good. A person may be kind, merciful, charitable, etc., but until he proves this by helping others, his goodness means precisely nothing to the world, in which case it means nothing to himself. We could go on about Aristotle, of course, but this list has gone on long enough. Honorable mentions are very many, so list them as you like.