Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

10 Lesser-Known Ancient Roman Traditions

Depending on your personal view, ancient Rome was responsible for giving the modern world a number of traditions, including various legal ideas, democracy, and some of our religious celebrations. However, there are still many ancient Roman traditions that are slightly obscure, mostly relegated to the dustbin of history. Here are some lesser known ones.

10Mos Maiorum

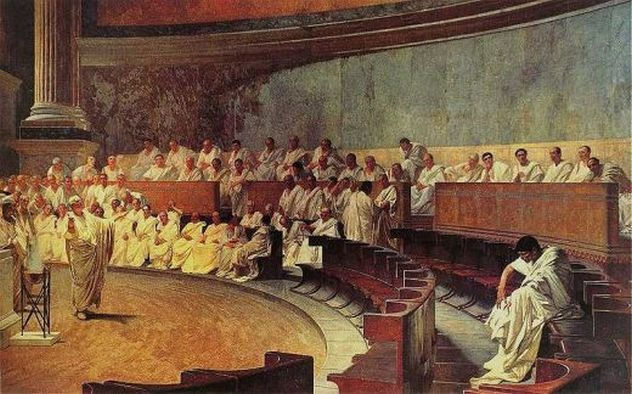

The mos maiorum was an unwritten code pertaining to behavioral customs mostly derived from the traditions of the Romans’ ancestors. Much like the Jews in the first song in Fiddler on the Roof, the Romans loved tradition and felt that moral decay would occur if they strayed too far from the ideals of the past. Therefore, obedience to the mos maiorum was seen as tantamount to maintaining a proper civilized Rome and was almost given legal standing.

There were occasions where breaking tradition was seen as subversive; in the case of legislation, it was considered customary to bring proposals before the Senate. Any magistrate who neglected to perform this duty ran the risk of being labeled a traitor. Even with the strict punishment handed down for certain offenses, it was still considered unwritten. As such, the transmission of the mos maiorum from one generation to the next was said to be the duty of the family, especially the paterfamilias (head of the household).

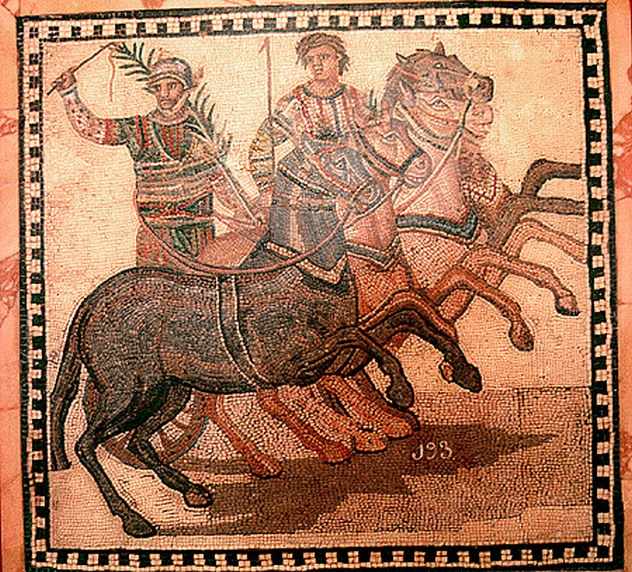

9Ludi

The ludi were public games that were normally held in conjunction with religious festivals, though there were occasional events which were secular in nature. Many of them were annual events, especially the religious ones, and the most famous was the Ludi Romani, which honored Jupiter and was held each September. (It’s the oldest of the ludi and was the only one held in Rome for 300 years after it first began.)

Ludi normally consisted of chariot races, as well as animal hunts. Later editions incorporated gladiatorial combat and there were even special ludi, which were strictly theatrical performances. The ludi with the largest gap in celebration was probably the Ludi Saeculares, or Secular Games. Held in honor of a saeculum, or the longest estimated human lifespan, the Ludi Saeculares were held once every 110 years. (Historian Zosimus actually blames the fall of the Roman Empire on the Romans neglecting to honor this ancient festival.)

8Dies Lustricus

Just as it is in our society today, the birth of a new child was seen as a joyous event, one which brought with it a number of interesting traditions. The dies lustricus, or “day of purification,” was an eight- or nine-day period after birth, which carried with it special meaning for the newborn. Healthcare and technology being what they were back then, a large percentage of children didn’t make it past one week, and the Romans felt that a child wasn’t officially a part of the family until the dies lustricus had passed.

Various rites were performed leading up the final day, including the laying of the baby on the ground and its subsequent raising to the sky by the father. (This was supposed to signify the father’s recognition of the child as one of his own.) At the conclusion of the dies lustricus, a baby was officially given a name, which is why babies who died early were left nameless. A special amulet—bulla for boys and lunula for girls—was also given to them during this period and it was meant to protect them from evil forces.

7Patria Potestas

Patria potestas, or “paternal power,” was one of the most prevalent traditions in ancient Rome. It greatly influenced the law of the time, as well as affecting our laws today. The power of a father over his children was seen as the highest of the land, with the children unable to go against their father’s wishes. Social convention usually kept abuses of power from becoming too widespread, though it was still up to the father as to what he wanted to do, especially in regard to punishment.

In addition, the father also had dominion over any of his grandchildren, or even his great-grandchildren. Although, in reality, many children were freed from patria potestas by the time they were in their mid-twenties, since the previous generation was normally dead already. One of the oldest traditions, patria potestas was said to have been granted by Romulus, and even gave a father control over his children’s possessions, which remained his until he died.

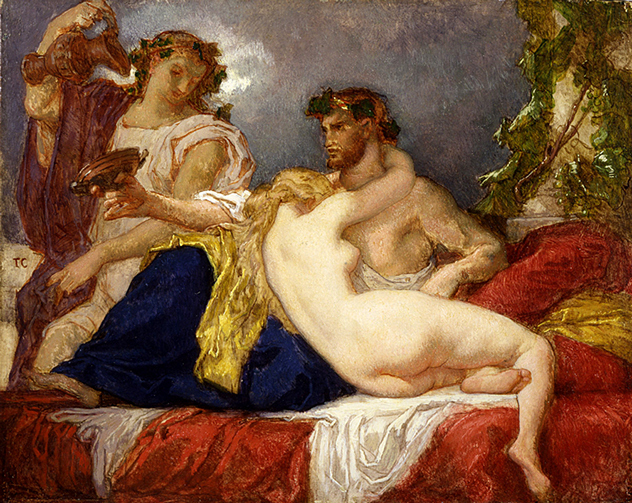

6Concubinage

A concubine in ancient Rome was slightly different from that of the traditional variety. First off, a man could only have one concubine at a time, and was not allowed to have a concubine if he was already married. In addition, the relationship between a man and his concubine had legal standing and was considered a step below marriage, though there were specific legal differences.

In fact, most women who became concubines were only not wives due to social standing, or a man’s wish not to complicate the inheritance of his wealth due to a previous marriage. Children born from concubinage were considered illegitimate; however, the father was still expected to provide for them while he was alive. Also, the concubine herself was not elevated to the same social status as the man—as opposed to a wife—and she was banned from worshiping Juno, the goddess of marriage.

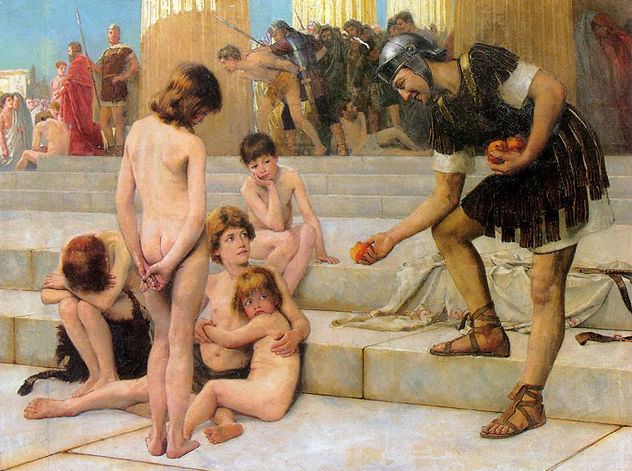

5Peregrini

Peregrini were people who were not citizens of Rome and the concept of the peregrini was vital to the success of the Roman Empire. Civil law, such as the ownership of property, was restricted in a lot of ways, but the harshest penalty for being a peregrini was that they were unable to marry a Roman citizen, unless extraordinary circumstances allowed for it. The Romans did, however, allow peregrini to retain the rights of their homeland. For example, Athenians were allowed to marry Athenians and be heirs to other Athenians.

Over time, the rights of Roman citizens began to take over the day-to-day interactions between Romans and non-Romans, so much so that peregrini were almost second-class citizens, barely better than a slave. However, this was all made moot in A.D. 212, when Emperor Caracalla declared all free men to be citizens of Rome, regardless of their place of birth.

4Poena Cullei

The Romans had laws for everything, many of which have been adopted by Western civilization into their own judicial systems. However, capital punishment was quite prevalent in ancient Rome, being used for a number of crimes that we would simply jail someone for today. Poena cullei was a special type of capital punishment, one which was reserved for a particular crime: parricide, or murder of a member of one’s family.

Once convicted, the murderer would have his face covered with a wolf’s skin and sandals were placed on his feet (presumably to keep him from defiling the air or the ground). He would now wait in prison until a sack was made for him. Once it was ready, a dog, monkey, snake, and rooster were placed in the sack, along with the murderer, and the sack was thrown into a river or the ocean.

3Homo Sacer

Another traditional Roman punishment, the status of homo sacer was given to those who broke oaths. Homo sacer translates best as “man who is set apart.” Those punished with this title were not allowed to be ritually sacrificed, but they could be killed by anyone, with impunity. Some people were deemed homo sacer by a group of vigilantes, without any actual legal standing. (It is believed this may have occurred in early Rome, since they lacked the standing forces necessary to enforce the law, allowing people to take matters into their own hands on occasion.)

In addition, any legal rights the convicted would have normally had, such as land ownership, were revoked, essentially ridding him of what made him a part of society. The Law of the Twelve Tables, the foundation of Roman law, specifically mentions homo sacer, making it the punishment for patrons who deceive their clients.

2Triumph

In ancient Rome, a triumph was an extraordinarily special ritual, a parade saved for a victorious general, and the highest honor that could be bestowed on a military man. (Although, the rite was abused in the later years of the Republic, with the aristocracy vying to outdo each other.) Various requirements, including a kill count, were set and the entire thing had to be approved, as well as paid for, by the Senate. When the Republic fell, all triumphs went to the Emperor, as he was seen as the commander-in-chief and all military honors went to him.

Basically, a long parade took place in Rome. Members of the Senate, musicians, sacrificial animals, and prisoners walked in front of the general, who had a gold crown held over his head by a slave. Bringing up the rear were his fellow soldiers, who traditionally sang songs poking fun at their commander; this was believed to ward off the evil eye. It culminated in the sacrifice of animals at the Temple of Jupiter, as well as the killing of the prisoners of war.

1Damnatio Memoriae

A practice common with nearly every ancient culture, and even some today, damnatio memoriae was the ritualistic and symbolic removal of a person from history. Seen as the worst punishment imaginable, worse than execution, the damned’s name was scratched from inscriptions, frescos with his face were painted over, and any statue was defaced, as if it was really him. It was normally reserved for the worst emperors in Roman history; Caligula and Nero escaped this punishment by having powerful friends, even after death.

Only three emperors are known to have been officially given this punishment, including Maximian, whose friend and co-emperor Diocletian is said to have been so stricken with grief that he died shortly after hearing the news. Obviously, it didn’t work as well in practice as it did in theory; we still know about everyone who was the subject of damnatio memoriae. Some scholars feel it may have served a cathartic purpose for the public, enabling them to vent their frustration over the failures of their leaders.