Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Politics

Politics 10 Political Scandals That Sent Crowds Into the Streets

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Facts About The Doge Meme

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Your Christmas Tree Is More Lit Than You Think

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Coolest Stars to Set Sail on The Love Boat

History

History 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the American National Anthem

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Funny Ways That Researchers Overthink Christmas

Politics

Politics 10 Political Scandals That Sent Crowds Into the Streets

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Facts About The Doge Meme

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Ways Your Christmas Tree Is More Lit Than You Think

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Coolest Stars to Set Sail on The Love Boat

History

History 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the American National Anthem

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

15 Interesting Women of Ancient Rome

Women in ancient Rome were not allowed any direct role in politics. Nevertheless, women often took on powerful roles behind the scenes, whether in the realm of their own family, or in the elite world of government. Here’s a list of some of the most influential and memorable ancient Roman women.

Aurelia Cotta, who lived from 120 to 54 BC, was the mother of Julius Caesar. Her husband died young, and before that, was away most of the time, so she was the one in charge of raising Caesar along with his two sisters (both named Julia – one the future grandmother of Augustus). She and her family lived in the Subura, a working class district in Rome, which was unusual for a highborn patrician family. She also raised Caesar’s daughter Julia after his wife Cornelia Cinna died. Aurelia was considered intelligent and independent. When Caesar was nearly executed at age 18 by the dictator Sulla, for refusing to divorce Cornelia Cinna, it was Aurelia who intervened. She headed a petition to Sulla that succeeded in saving her son’s life.

Lucilla was born around 150 AD, to the emperor Marcus Aurelius. She married her father’s co-ruler Lucius Verus at about age 14. After Lucius Verus died, Lucilla remarried, and traveled with her second husband and Marcus Aurelius during his Danube military campaign. It was during this time that Marcus Aurelius died, and Commodus became emperor. Commodus’ actions while emperor became increasingly disturbing, and an assassination plot was hatched by Lucilla, her nephew, her daughter, and two cousins. Lucilla planned to take over as empress afterwards, but the scheme failed. As her nephew attempted to stab Commodus, he shouted, “Here is the dagger the senate sends you!” This was ample warning to Commodus’ guards. The male members of the plot were immediately put to death, while Lucilla, her daughter, and cousin were banished to Capri. However, Commodus had them executed also a year later, in 182 AD. A character based on Lucilla appears in the movie Gladiator.

Cornelia Africana was the daughter of Scipio Africanus, famous for his victory against Hannibal in the Second Punic War. She died at age 90 in 100 BC, and was remembered by the Romans as an exemplar of virtue. Out of the 12 children she had, only Sempronia, Tiberius Gracchus, and Gaius Gracchus survived. When her husband died, she did not remarry, and took over the education of her children. When Tiberius and Gaius became involved in controversy because of their populist political reforms, they never lost the support of their mother. Eventually, she lost both her sons when they were killed on different occasions at the hands of the conservative senate. When Cornelia herself died, a statue was dedicated to her. Over time, Cornelia became an increasingly idealized figure, with emphasis switching from her own education and rhetorical skills to her image as the perfect Roman mother.

Hortensia was an orator who made her biggest impact with a speech she gave before the Second Triumvirate (Mark Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus) in 42 BC. At this time, the Second Triumvirate was at war with Brutus and Cassius, among others of Caesar’s assassins. They killed the rich and confiscated their property to raise money, but still did not have sufficient revenue. To this end, they decided to impose a tax on almost 1500 wealthy Roman women. Not having any say in politics themselves, the women were furious at being taxed for a war they had nothing to do with. The women arrived at the forum with Hortensia as a representative to make a speech to the triumvirs. Here’s a quote from her speech:

“You have already deprived us of our fathers, our sons, our husbands, and our brothers, whom you accused of having wronged you; if you take away our property also, you reduce us to a condition unbecoming our birth, our manners, our sex. Why should we pay taxes when we have no part in the honors, the commands, the state-craft, for which you contend against each other with such harmful results? ‘Because this is a time of war,’ do you say? When have there not been wars, and when have taxes ever been imposed on women, who are exempted by their sex among all mankind?”

Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus, were not pleased by this display, but were unable to get Hortensia to leave the rostra. Eventually, they agreed to tax only 400 women and to borrow the rest from men.

Livilla was born in 13 BC, and was the sister of the emperor Claudius. Just as Claudius was constantly derided by his mother, his sister was also extremely contemptuous of him. Livilla expected to one day become empress after she married Augustus’ grandson Gaius, but Gaius was killed. Livilla’s fame comes mainly from her affair with Sejanus, and attempt with him to take power. Sejanus was the praetorian prefect of the emperor Tiberius. When Tiberius abandoned Rome for his infamous island adventures at Capri, Sejanus began gaining more and more power, eliminating his opponents. Livilla was at this time married to Tiberius’ son Drusus. When he died, no one suspected anything, but it was later discovered that Livilla and Sejanus had poisoned him. The two planned to marry, but Livilla’s mother wrote to Tiberius that they were attempting to overthrow him. Sejanus was sentenced to death, and he along with his children and followers were murdered. As for Livilla, Dio says that Tiberius left her fate up to her mother Antonia the Younger, who chose to lock her daughter in a room until she starved to death. A “condemnation of memory” was voted for Livilla, so today it is difficult to identify possible portraits of her.

Helena was born around 250 AD. It is thought that she first lived in Drepanum, later called Helenopolis. Saint Ambrose said she was stabularia, which can mean either innkeeper or stable maid. It is possible that she met the future emperor Constantius while he was fighting a campaign in Asia Minor. The story goes that when Constantius saw that they were wearing the same bracelet, he decided it was a sign they should marry. Some sources refer to Helena as the emperor’s concubine, while others say they were officially married. In any case, Constantius eventually left Helena for a woman of higher birth. Helena’s son by Constantius was Constantine, who would become the first Christian emperor. Helena found what was believed to be the True Cross and other relics while in Jerusalem. She was famous for her kindness, and is considered today to be a saint.

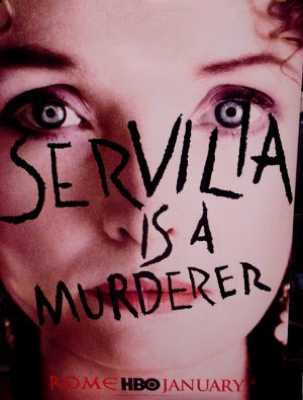

The half sister of Cato the Younger, the mistress of Caesar, the mother in law of Cassius, and the mother of Brutus, Servilia was influential through her connections to many famous Romans. Her parents died when she was young, and she and her siblings were brought up by their uncle Livius Drusus. Unfortunately, he was assassinated for trying to gain citizenship for Italian allies. Servilia’s first husband – Brutus’ father – was killed by Pompey the Great. She eventually began an affair with Julius Caesar, and rumors circulated saying that her daughter Junia Tertia was actually Caesar’s. Cicero also made a remark about how Servilia was letting Caesar sleep with Junia Tertia (obviously, or should I say, hopefully, these pieces of gossip were not both true). It is also believed that Caesar’s daughter Julia was originally betrothed to Brutus (there is a bit of confusion here, since Brutus’ name temporarily changed when he was adopted by Servilia’s brother).

One amusing event involving Servilia and Caesar occurred when Caesar was handed a letter written by her during the debates over the Catiline conspiracy. Cato said that Caesar was receiving correspondences from the conspirators, and ordered that the letter be read out loud. Much to Cato’s embarrassment, it turned out to be a love letter by his own sister. Servilia’s relationship with Caesar in turn affected Caesar’s relationship with Brutus. For example, when Caesar was fighting Pompey in the Battle of Pharsalus, he ordered that Brutus, who was on Pompey’s side, not be harmed in any way. When Brutus and Cassius were plotting Caesar’s assassination, they met at Servilia’s house. It is unknown whether or not she knew about their plans. Servilia died of natural causes in 42 BC.

Porcia lived from around 70 to 42 BC. Porcia was the daughter of Cato the Younger, but is most famous as the wife to Marcus Junius Brutus. Porcia was considered to be both kind and brave, and was a lover of philosophy. Her first marriage was to Bibulus, an ally of Cato. Quintus Hortenius requested that Bibulus let him have Porcia for his wife, but he would not let her be taken from him. Hortensius then made the unusual request that he allow Porcia just live with him until she produced a son. Cato divorced his wife Marcia and let Hortensius marry her instead, which was a strange solution since Cato by all accounts loved his wife. When Hortensius died, Marcia moved back in with Cato. Bibulus died after Pompey was defeated by Caesar, and Cato committed suicide by stabbing himself and pulling out his intestines when his friends tried to revive him. Left without a husband or a father, and still very young, it was around this time that Porcia married her cousin Brutus. This was not well-received by many (especially his mother Servilia who hated Cato) because Brutus divorced his wife without giving any reason in order to marry Porcia.

Only Cato’s supporters, such as Cicero, approved of the marriage. Porcia was very devoted to Brutus, and one of the only women, if not the only woman, to be involved in the conspiracy against Caesar. Plutarch writes that Porcia stabbed herself in the leg to show Brutus that she could be trusted with any of his secrets, even under torture. When the assassins had to flee Rome, Porcia stayed behind. Brutus said of her: “Though the natural weakness of her body hinders her from doing what only the strength of men can perform, she has a mind as valiant and as active for the good of her country as the best of us.” The circumstances of Porcia’s death are uncertain. One of the most common accounts is that she committed suicide after hearing of Brutus’s death, either by swallowing hot coals or burning charcoal in a room without ventilation.

Octavia lived from 69 to 11 BC, and was the older sister of Octavian (later known as Augustus). Although Julius Caesar was her great uncle, she married one of his opponents, Marcellus, who she had 3 children with. After Marcellus died, she married Mark Antony. This was to help secure the alliance between Antony and Octavian who were, to say the least, not always on great terms with each other. However, Antony left Octavia for Queen Cleopatra, who he had an affair with in the past, and already had twins with. Octavia remained loyal to Antony, and she became a sort of negotiator between Antony and Octavian.

After Antony had received the money and troops he needed from Octavia to fight a campaign in the east, he divorced her. This was one of the many actions of Antony that Octavian used to paint him and Cleopatra in as bad a light as possible. Octavia never remarried, and after Antony’s suicide, she took in his 4 children by Fulvia and Cleopatra, and cared for them along with her other children. When her son Marcellus died, she remained in mourning until death. Octavia was highly respected by her brother, and was a role model for many Roman women.

Messalina was born around 20 AD. She was a cousin of Nero and Caligula, and became empress when she married Claudius. Along with Augustus’ daughter Julia (who he had banished for sleeping with so many different men), Messalina is probably one of the most notoriously promiscuous women of Rome. In 37 AD, Messalina married Claudius, who was at least 30 years older than her. At this time Caligula was still emperor. Claudius doted on Messalina, and after he became emperor, Messalina used his affection for her to get whatever she wanted. Since Claudius was old, she realized how precarious her position was, and was ruthless to that extent. She ordered that Claudius exile or execute anyone who displeased her or who she felt threatened by.

Unfortunately, this was a good number of people. For all his good qualities as emperor, Claudius became known for being easily manipulated by his wife. The account of Messalina competing with a prostitute to see who could have sex with the most people in one night was first recorded by Pliny the Elder. Pliny says that, with 25 partners, Messalina won. Messalina’s most famous affair is the one she had with the senator Gaius Silius. She told Silius to divorce his wife, which he did. Silius and Messalina planned to kill Claudius, and make Silius emperor. While still married to Claudius, Messalina married Silius. Of course, this was all discovered, and Claudius had the two put to death.

Julia Domna lived from 170 to 217 AD. She was the wife of the emperor Septimius Severus, and the mother of the emperors Caracalla and Geta. Born in Syria, her father was the high priest of the temple of Elagabal. Julia and Severus had a happy relationship, and she would often advise him politically. She traveled with him during his military campaigns, which was unusual for a woman. Many Romans felt she wielded an inappropriate amount of power over the empire whenever her husband was gone on a campaign. She often faced accusations of adultery or treason, but none of these were ever proven. After Severus died, Julia tried to help Geta and Caracalla rule successfully as co-emperors. Caracalla eventually had his brother killed. After that, things became a bit more strained between Caracalla and his mother, but she still traveled with him during his campaigns.

When Caracalla was assassinated, Julia committed suicide. Julia’s sister, Julia Maesa, was also an influential woman, and helped engineer the plot to overthrow Macrinus so that her grandson Elagabalus could become emperor. When Elagabalus turned out to be a complete and utter failure of an emperor, she began promoting her other grandson Alexander Severus. After Elagabalus was murdered along with his mother, Alexander became emperor. Julia Mamaea, another relation of Julia Domna’s, came to exercise power. Her son Alexander was barely 14, and she essentially had control over running the empire, until she was killed along with Alexander during a mutiny.

Agrippina the Elder lived from 14 BC to 33 AD. She was the granddaughter of Augustus, daughter of Augustus’s right hand man Agrippa, and the wife of the beloved general Germanicus. After Agrippa died, Agrippina’s mother married Tiberius. This was an unhappy marriage, as Tiberius had been forced to divorce Vipsania, who he was deeply in love with. Agrippina never saw her mother again after she was exiled for adultery. Germanicus and Agrippina had six children who lived to be adults, including Nero (not the emperor), Drusus, Gaius (later known as Caligula), Drusilla, Livilla, and Agrippina the Younger. Agrippina went with Germanicus on his campaigns, along with their children. They would dress their toddler in a little army outfit, and this is how Gaius got the nickname Caligula, which means Little Boots.

After Tiberius became emperor, he became jealous of Germanicus’ popularity, who was preferred by many for the position. It was believed by many that it was on Tiberius’ orders that Germanicus was poisoned in Antioch. Agrippina believed her husband had certainly been murdered, but the truth was never found out. She made her dislike of Tiberius clear, and accused him of trying to poison her as he did her husband. Tiberius didn’t trust her either, and had her elder sons Nero and Drusus arrested and then left to starve to death. Tiberius then banished Agrippina on false charges. Exiled to the same island her mother once had been, Agrippina was treated violently, and lost an eye while being flogged. Like her sons, Agrippina eventually died of starvation. As a side note to Agrippina’s tragic story, her youngest son Caligula was not only spared by Tiberius, but brought to live with him on Capri. I imagine that it would be slightly uncomfortable living with the man responsible for the deaths of nearly everyone in your family.

Agrippina the Younger, daughter of Agrippina the Elder, lived from 15 to 59 AD. Around age 13, she married Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Ahenobarbus had a reputation for dishonesty, violence, and traffic violations (he once ran over a child in the street). Agrippina and Ahenobarbus had a son named Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, who would later be called Nero and eventually become emperor. When Caligula became emperor he gave Agrippina, along with her sisters Drusilla and Livilla, many privileges and honors. When Caligula’s favorite sister Drusilla (who he often treated more like a wife) died, he was devastated, and also became colder to Agrippina and Livilla. The sisters became involved in a plot to assassinate Caligula, but it was discovered, and they were exiled. When Claudius was made emperor, he brought his nieces Agrippina and Livilla back from exile. After Claudius’ wife Messalina was killed, the freedman Pallas advised him to marry Agrippina. Agrippina and Pallas were having an affair, and he wanted to see his mistress gain power.

Other advisers presented different options to him, but Pallas argued that marrying Agrippina would help connect the Julian and Claudian sides of the family. Claudius decided to marry Agrippina, which was controversial in Rome, where it was not considered acceptable for a man to marry his niece. Just as Messalina had done, Agrippina worked to eliminate anyone who threatened her or Nero’s position. Even though Claudius had a biological son, Agrippina convinced Claudius to adopt Nero and make him his heir. Claudius seemed to begin favoring his own son Britannicus again, and this is the most likely motivation for Agrippina poisoning Claudius. After Claudius was dead, Nero became emperor, and Agrippina began exercising power through her son. Just as Agrippina was accused of incest with Caligula, she was also accused of using sex as a means of controlling Nero. Nero eventually began to resent his mother for the control she had over him. After many failed elaborate attempts on Agrippina’s life, Nero eventually resorted to the tried and true method of stabbing. When the assassins came to kill Agrippina, she told them to stab her in her womb.

Fulvia was one of the most politically involved women of the Roman Republic. She lived from 83 to 40 BC, and was the great granddaughter of Cornelia Africana. Fulvia’s first husband was Publius Clodius, who is probably best known for sneaking into the Bona Dea festival dressed as a woman in order to meet up with Julius Caesar’s wife. Clodius was a populist politician, and Fulvia was with him constantly. After Clodius was killed by his political opponent Milo, Fulvia dragged his body through Rome and incited a riot among Clodius’ followers. Fulvia gave a testimony during the trial of Milo, who was condemned to exile. When Clodius died, the power he had over many gangs in Rome transferred to her. Fulvia’s second marriage was to another popular politician, Scribonius Curio. Curio was also killed, while fighting for Caesar. Fulvia’s final marriage was to Mark Antony, who was also a good friend of Curio. In one of Cicero’s Philippic speeches, he goes on for some time about the nature of Curio and Antony’s relationship – whether completely true or not, it makes for entertaining reading. Cicero also derided the relationship between Fulvia and Antony, saying that he only married her because he needed her money. Fulvia defended Antony after Cicero’s many speeches against him, and helped her husband to gain power through the gangs of Clodius she still controlled.

After Caesar died and Antony joined the Second Triumirate, Fulvia was involved in the proscriptions. After Antony had Cicero murdered, Dio describes Fulvia stabbing his tongue with one of her hairpins. When Antony and Octavian went to fight Brutus and Cassius, Fulvia was essentially left in charge of Rome. Octavian, who had married and divorced one of Fulvia’s daughters, believed Fulvia was gaining too much power, and becoming too ambitious. Along with Antony’s brother Lucius, Fulvia raised legions to fight Octavian. Around this time Octavian wrote an epigram about Fulvia: “Because Antony fucks Glaphyra, Fulvia is determined to punish me by making me fuck her in turn. I fuck Fuliva? What if Manius [freedman of Fulvia] begged me to sodomize him, would I do it? I think not, if I were in my right mind. ‘Either fuck me or let us fight,’ says she. Ah, but my cock is dearer to me than life itself. Let the trumpets sound.” Eventually Lucius surrendered to Octavian, and Fulvia escaped to Greece. When Antony met her there, he was outraged that she had incited a war against Octavian without his permission. Soon after this, Fulvia died of unknown causes.

Livia Drusilla, the first empress of Rome, lived from 58 BC to 29 AD. Livia was first married to Tiberius Claudius Nero, who she had her son Tiberius by. When Livia met Octavian, he fell in love with her, even though she was married and pregnant with Drusus, her second son. Octavian was also married at the time, to Scribonia. On the same day that Scribonia gave birth to Octavian’s daughter Julia, he divorced her, and then forced Tiberius Claudius Nero to divorce Livia. Awkwardly enough, Tiberius Claudius was the one to give away his ex-wife in Livia and Octavian’s wedding ceremony. Livia and Octavian (Augustus) would be married for over 50 years. Despite the fact that they both had children from previous marriages, they never were able to have children. During Augustus’ long reign as emperor, Livia was a constant adviser. Since Augustus had no sons of his own, Livia began promoting her own sons as heirs, and it was around this time that rumors began spreading about Livia’s habit of killing anyone who got in the way their accession, including Augustus’ nephew Marcellus and his grandsons. It was even said that she poisoned Augustus with figs, to prevent him from changing his heir from her son Tiberius to someone else.

The image of Livia as essentially a power mad serial killer was possibly common at the time because of the Roman idea of the evil step-mother figure. In modern times, people still often picture Livia in this way, such as in I, Claudius. In reality, despite her ambitions for Tiberius and the odd coincidental deaths of Augustus’ heirs, there’s no proof to support the murders. Perhaps there’s something morbidly appealing in the idea that Augustus – the man who not only survived illness after illness, civil war after civil war, but lived to reform the Roman Republic and rule over it for roughly half a century – ended up getting killed by some figs from his beloved wife. Augustus left Livia a third of his property, and also adopted her. In the biography of Augustus by Anthony Everitt, he writes that there is not a definite reason as to why Augustus adopted his wife. He suggests that it was an acknowledgement of all the work Livia did for him and counseling she gave him. Tiberius, who did not have any desire to be emperor in the first place, did not appreciate Livia’s political advice, and began to find his mother overbearing. When Livia died, he did not return to Rome from Capri, but sent Caligula to deliver her eulogy. There were many honors granted to Livia after her death, but Tiberius had them all vetoed.