Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

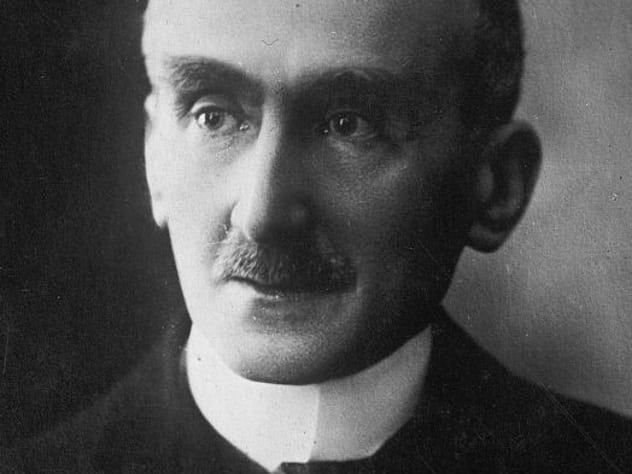

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Interesting Conceptions On The Nature Of Time

Time is so ubiquitous that it covers absolutely everything we do, encapsulating our own existence and that of everything we know. It could be said that there is nothing that exists outside of time. Time is the flowing in a forward direction of all things that exist, an indefinite continued progress, every second absorbing the last, consuming it as we move forward in the space-time continuum. You are somewhere reading this right now, and you are also some-when.

But for such a permanent fixture of our lives, time is actually quite flexible and far more descript than the given intuition we have of it. How can time affect our lives, our thoughts, our perceptions? And is time as straightforward as it seems to our intuition, our experience of it? What are the different ways we can think about time, and what can we learn from it? Time can be a fixed point, such as 11:14 PM on Tuesday, May 12, or a measurement between two points, as in one second or one minute in the continuum of the flow of all things. This very second will never exist again. Here are ten interesting conceptions of time to give you a more nuanced view on this fascinating part of the fabric of our existence.

10 Linear Time

This is the first, most intuitive, version of time there is, the straightforward experience that views time as a line, streaming seamlessly from one moment to the next. When we plot time on a straight line, that’s linear time, a linear representation of how time works. In linear time, each moment must necessarily succeed the previous as time flows and each second melts into the next.

This is almost naturally how we look at time, as moving in one direction, from past to future, but linear time is by far nowhere near the only conception of time. By contrast, nonlinear time is a concept that modern science and philosophy are formulating which states that, unlike the typical past-present-future mode of existing that all things share, there could be multiple versions of this very present moment we’re currently inhabiting, experienced differently by the subjects and objects within each.[1] According to nonlinear time, temporal references are just human markers that we use to store and keep track of various moments through the transition of time, but this by no means implies that time is necessarily straightforward. In fact, nonlinear time is probably the soundest way of looking at time between two moments.

9 Circular Time

Circular time is also quite familiar to us; it’s a time frame that repeats, typically on a predictable routine, like the clock that goes around and around and around infinitely, always coming back to the same numbers it began with. We might also look at weeks, months, and years as circular as well. The concept of circular time dates back to ancient Hebrew philosophy.[2] Because time is circular, according to the ancient Hebrews, it is also unending.

Certainly, many ancient cultures used the clockwork-like movements of the Sun and Moon to plant, plan, and predict the futures of their lives. The ancient Greeks were very proficient in astronomy and agriculture, both which depend heavily on the concept of circular time, or cyclical time. Thus, they, the Maya, and many more ancient cultures thought that time was circular and that events ebbed and flowed, coming and going, being born and dying away, only to come back again.

It may seem strange to us today, but for most of human history, time was viewed as entirely circular; they did not see it as linear, streaming forward from one moment into the next, and probably couldn’t even conceptualize time as such. Days into nights, back into days, only to be swallowed again by the night. In fact, the Gregorian Calendar, the most widely used calendar in the world that we all know and love in Western culture today, wasn’t even formulated until 1582.

8 Real Duration

The next fascinating way of looking at time is pretty distinct from what we’ve discussed so far. This is real duration (also just called duration), from the philosopher Henri Bergson. For Bergson, real duration is our “lived time” or the time we experience from within and our interpretation of that, which can be radically different from the time we see objectively that is measured by the physical sciences. Unlike linear or circular time, which are always the same in quality and experience, real duration is how we experience time from the inside of our individual worldviews: Let’s say you take a bite out of some yogurt and then sit back and stare out of a window for one minute in linear time. The next minute, someone strikes your foot as hard as they can with a hammer—those two minutes are going to feel like completely different types of time because the qualities of experience that we are encountering with each of these are extremely different.

Real duration, unlike the other forms of time mentioned, cannot be separated from the experience of that duration of time. This is interesting to note, as Bergson criticized science strongly for its application of spatial concepts onto time and making it a rigid, mathematical, soul-dead thing, devoid of human or animal experience.[3] This raises the question: What good is any notion of time if there isn’t someone there to perceive it? Unlike time, real duration shares its features with the experiencer’s intensity, situation, events, and surroundings and can only be lived with reference to the qualitative experiences taking place in that frame of time. After all, would you consider a year in a coma and a year doing what you loved all day, every day, to be the same? In real duration, time is completely dependent upon what happens during that time frame.

7 Temporality

Temporality is another philosophical concept that pertains to time. Temporality is the philosophical study of the past, present, and future, and what they mean to us, the conscious agents living our lives. If time is the study of a linear path along an axis, or a circular motion by which all things repeat, and real duration is the experience of time as we live it from within, then temporality is the focus on how things change. Temporality is the real effects of time, as a banana goes from a state of being unripe, to ripe, to rotten, or how a body slowly decomposes over a series of days, weeks, months, and years. While the days, weeks, months, and years are the measurements of time, the concrete process of decomposition takes place through temporality.

Since the time of Augustine, philosophers have sought to tease out the difference between time and temporality by noting that time, unlike temporality, could only be measured outside of the framework of eternity, while temporality was the process of going toward eternity, and as a pure process, rather than measurement, time was an intrinsic part of the making (or unfolding) of eternity.[4] As each moment flows seamlessly into the next, the human existence cannot take place without this constant transition into the future. Unlike linear time, which is an abstraction between two moments and which inherently means the measurement of time must stop, temporality is constant, ongoing, and forever in flux and must take place in reference to other changing things.

6 Relationism

Relationism is a concept of time that has been around for a very long time. It’s one half of the dichotomy between relationism and absolutism (sometimes also referred to as substantialism), which has been an ongoing debate in philosophy and the sciences. Relationism holds that time cannot exist outside of the changing events and motion of objects traversing through time which make up the unfolding of time as the universe experiences it.[5] Sort of like the debate between temporality and linear time, realtionism seeks to explain that time doesn’t simply just unfold in a forward direction abstractly, but rather, it is an inherent product of the change which is bestowed upon the objects which compose the totality of space. In short, relationism makes the claim that without change, there cannot be time, and the two are one and the same.

The more important philosophical underpinning here is that space and time, in the theory of relationism, don’t exist independently as actual objects or things but are merely abstractions, mathematical representations which don’t really have anything to do with the real-world objects which make up the space-time continuum.

5 Absolutism

Absolutism is quite the opposite view from relationism: Close your eyes for a second and picture an expansion, a vast recess of black, empty space. No light exists; nothing is there. It’s literally just a massive empty void of sweet, beautiful nothingness. Does time exist here? Does it exist without any objects whatsoever to fill it up, any change going on? Is time a fabric of this hypothetical universe you’re dreaming up? Or is each moment the same as the next, thus negating time as being a concept that has any meaning? Furthermore, if time is a measurement, what would be measured in such a place? And if science (or philosophy) is the discussion of concrete facts of reality, do such hypotheticals have such a place in our thought processes, or should we stick to that which is falsifiable in the name of intellectual honesty?

Regardless of your thoughts on these questions, substantialism basically holds that time and space are sort of containers or frameworks in which the objects of our universe exist, rather than the idea that space-time is directly relative to the objects that do exist within it.[6] So, do you think time and space can exist in a vacuum of nothingness?

4 Presentism

Did you ever have one of those deep, pondering moments where you wondered if right now is all that exists and all that you are? Like right now, this very moment? Presentism is a very real philosophical line of thought wherein proponents believe that the moment you’re inhibiting right now is all that can be said to exist, that the past and the future aren’t real but rather figments of our imagination.[7]

While presentism is, for all intents and purposes, actually quite true on a personal level, no matter how counterintuitive it may seem, as we know we weren’t simply placed right here in this moment and obviously have an extended past from which we learned and became, presentism even extends to objects and the nature of the things which inhibit our universe. Presentism goes a step further in saying that the objects which exist here and now are the only things that can be said to exist, and anything that is supposed to have existed before, like your cell phone five seconds ago, was wiped away and destroyed as each moment bled into the next—that the present reality is the only reality.

3 Dimensionality

Since Phythagoras introduced the three-dimensional model of space we know and love today, the dimensions of height, width, and length, time and space have sat neatly side by side. Time, it was seen, has always been the fourth dimension. For centuries, space and time were treated as separate entities until around the late 1800s, when the question began to be proposed and finally came to a head with Einstein’s theory of relativity: Are time and space one solid fabric of existence called space-time (or time-space)?

Dimensionality refers to the debate pertaining to where exactly time fits into the dimensions of space. Or are they one? This question is an ancient one—can time exist independently without space? Or can space exist without time? This has brought us to the prevailing doctrine, the idea of four-dimensional space-time, where you cannot tease out time from space. The X, Y, and Z axis, along with the place in time, are solidified into one fluid fabric. This explains much of the underpinnings of our modern science, thanks to the works of Albert Einstein.[8]

2 Metabolic Influence

Modern science has begun to unveil some seriously strange things since we’ve unhinged time from its basic circular and linear conceptions. One of the newer developments is related to relative time, in how objects and entities experience times in different ways, at different rates, or as unfolding at different speeds. There is a connection between metabolic rate and time perception. In short, smaller animals with higher metabolic rates, like mice and hummingbirds, experience time as slower and, accordingly, seem to act in time faster.[9] One quick look at a hummingbird speeding around or a mouse zipping through your kitchen, and you wonder how such a small animal with comparatively tiny muscles can move so quickly compared to larger humans with our slow, cumbersome motions.

This isn’t actually just something that involves different species; it’s currently believed that as children, our higher metabolic rate is the reason we experience time as so slow, with days feeling like years. Of course, as anyone who’s lived long enough can testify, the longer you live, the more time seems to speed up. This isn’t just because of our experience or “getting used to” time but because our metabolic rates are slowing down as we age.

1 Animal Perception Of Time

You’ve heard of “dog years?” Well, it turns out there actually is some truth behind the idea. Perception-wise, smaller animals live in a slow-motion existence quite different from our own.[10] Imagine for a second that time isn’t a fixed thing, that the real duration, or experienced time we spoke of earlier, is the central unit of time. Then it would be safe to say that different animals could be programmed to “tick” each second by at a different rate of experience. The fundamental rate that each moment perceptively moves into the next would be faster for some animals and slower for others—this actually seems to be the case, as far as modern science can tell.

Imagine for a second your computer is the fundamental timekeeper. As we all know every time we get a newer, faster device, computers process bits of information at different rates, so one can only infer that the computer’s processing speed would be its ability to decipher time as it unfolds from the inside. Thus, time is flexible, relative to the speed at which our brains can process the incoming data, and the difference between different organisms is none other than the metabolism, the fundamental rate which an organism performs all of its life processes. This, of course, all takes place on the biological level. Dogs, for example, don’t experience time the same way humans do because they lack the memory and recall ability that we have with which to reference past events. They understand time through a series of repeated biological functions, whereas we experience them in reference to our concrete memories, which we, unlike they, can recall at a moment’s notice for a rough idea of the events which are transpiring now and what to expect of their duration.

As Einstein himself once said, “When a man sits with a pretty girl for an hour, it seems like a minute. But let him sit on a hot stove for a minute—then it’s longer than any hour. That’s relativity!” So time is, at best, a flexible construct of the mind, one that has many faces to it, many ways of looking at and experiencing it. As we progress into the future, our understanding of time will only get more and more bizarre and unusual.

Still love the dark stuff, psychology, philosophy, and history. This was definitely a fun list to do.

For more ideas about time that are hard to wrap your head around, check out 10 Out-Of-This-Universe Ideas About Time Travel and 10 Mind-Bending Theoretical Dimensions In Space And Time.