Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Top 10 Discoveries Adding To Debates About Ancient Humans

The lives of ancient humans remain a magnetic topic. To help piece together extinct cultures, behaviors, and origins, experts use two tools that sometimes provoke more debates than answers: physical evidence and theories. Scholarly debates can become so heated that only new discoveries can break the stalemates. However, sometimes, new “breakthroughs” are so controversial that they add more fuel to the fire.

10 Carthaginian Child Sacrifice

Most scholars dismiss ancient accounts of Carthaginian child sacrifice as propaganda invented by the Greeks or Romans. The Roman historian Diodorus described a horrific statue in Carthage where babies rolled down the idol’s hands into a pit of fire.

The debate over whether the Carthaginians killed their own offspring began in the early 20th century. Cemeteries discovered in Carthage held the cremated remains of babies, and more were found at other Carthaginian settlements in Sardinia and Sicily.

The tiny bones were arranged in urns in an identical manner to the sacrificed animals found on-site. Some babies and animals were interred in the same containers. The headstones made no mention of how the children died or their identities. Instead, inscriptions praised the gods for favors received or made requests for future aid.[1]

Scholars who believe that the Carthaginians ritually murdered infants limit the practice to the elite classes since cremation was pricey. These researchers also feel that it didn’t happen regularly, but resistance from opposing colleagues remains staunch. The result is one of the most embittered debates to arise from classical archaeology.

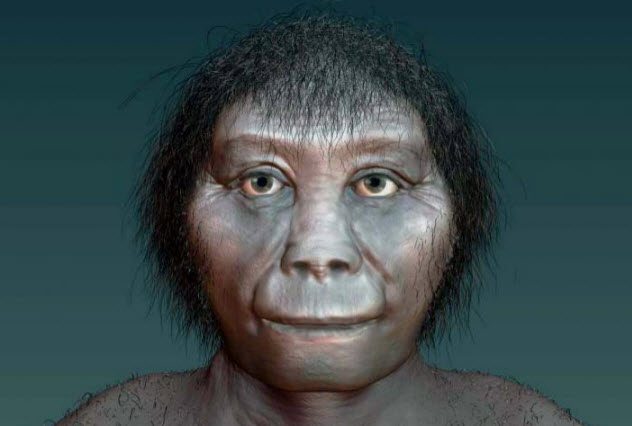

9 Hobbit Ancestors

When the miniature human species was discovered in 2003, Homo floresiensis quickly earned the nickname “the hobbits.” They walked the Indonesian island of Flores around 54,000 years ago, and who came before them remains a heated bone of contention between anthropologists.

In 2010, a study tried to confirm or bust the leading belief that they evolved from the bigger Homo erectus. Previous researchers only investigated the hobbit’s skull and jaw. Since Homo erectus was the only other early hominid found in the area, the ancestor assumption grew.

The 2010 study also examined the limbs, shoulders, and teeth. What they found was odd. Evolution moves a species forward, but Homo floresiensis was more primitive than its supposed ancestor.

The two didn’t link smoothly on the family tree, either. Instead, the hobbit appeared to be a sister species of Homo habilis, who dwelled in Africa 1.75 million years ago. Sister species share a common ancestor—in this case, one somewhere in Africa.

While the ancestor of Homo floresiensis remains unidentified, the research also found that Homo floresiensis is likely older than Homo habilis, making Homo floresiensis one of the earliest branches in the human story.[2]

8 The Sediba Child

Like the hobbits, the immediate ancestor of the genus Homo is a riddle. In 2008, a paleoanthropologist investigating a cave in Malapa, South Africa, found several skeletons. One belonged to a remarkably complete child.

Freshly named Australopithecus sediba, the youngster became celebrated as the sought-after missing piece. Other experts in the field aren’t buying it. In fact, they believe that the boy doesn’t belong to the human lineage at all but to another hominid line.[3]

Its narrow cheekbones are early Homo. But at 1.98 million years old, the species is too young to be the main ancestor. That honor belongs to an unidentified australopithecine that existed 2–3 million years ago.

They also maintain that the child, when digitally aged, closely resembles Australopithecus africanus adults, an older nonhuman hominid. A related debate considers Australopithecus afarensis (the famous Lucy fossil) as the best candidate.

Believers claim that the new kid has more humanlike traits than the 3.2-million-year-old Lucy, and extensive adjustments had to occur for the face to resemble Australopithecus africanus. Both sides agree that the only solution is to recover the head of an adult Australopithecus sediba.

7 The Aroeira Cranium

A newly discovered skull may help settle the debate surrounding the ancestry of Neanderthals. Researchers know that different Homo species settled Europe and Asia about 500,000 years ago and one of them evolved into the Neanderthals.

The 400,000-year-old cranium is thought to be a member of this archaic ancestral group. Found in 2014 in Portugal’s cave of Aroeira, the skull possessed mixed traits never before seen in fossil humans.

Some of the features strongly linking it to the Neanderthals include a fused brow ridge. Its age also clocks with the Middle Pleistocene, which was marked by the arrival of the hominids from which the Neanderthals later came.

The cranium’s rarity and value stems from the fact that most other Middle Pleistocene finds are difficult to date correctly. The Aroeira skull’s age could be accurately dated thanks to hand axes and animal remains found alongside it.[4]

Besides giving priceless clues about the origins of the Neanderthals, the fossil’s features could aid those trying to understand how different ancient hominids in Europe evolved and are related to each other.

6 The Arabian Collection

In southern Arabia, archaeologists went cave digging in the mountain known as Jebel Faya. They were rewarded with a cache of history-altering instruments. The stone artifacts included hand axes and tools fashioned for cutting, scraping, and piercing.

While that doesn’t move the earth, the collection’s age and location shook conventional wisdom. It was accepted that people first migrated in waves out of Africa between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago. Yet, the Jebel Faya haul came with the creaky age of 125,000 years.

This means that people packed up their furs and families and left Africa a whopping 55,000 years earlier than the history books believe. Some of the axes and blades had a nearly identical flavor to those made by humans in east Africa.[5]

Like many other finds that fly in the face of accepted history, it caused division among scholars. In this case, those opposed to the idea of an earlier departure reject the notion that the tools were made by modern humans that hailed from Africa.

That the cave was a shelter to humans later on isn’t debatable. Objects from the Iron, Bronze, and Neolithic periods were previously excavated at the site.

5 Mankind’s Mediterranean Cradle

A lower jaw from Greece and a tooth from Bulgaria could challenge the entrenched motto that Africa is the cradle of mankind. Both samples belong to Graecopithecus freybergi.

When experts recently examined the two specimens, they concluded that the samples weren’t from an animal. Instead, they’re likely from the first prehuman following the chimpanzee-human split from their common ancestor whose exact territory remains a pivotal debate in paleoanthropology.

They based their conclusions on the shape of the dental roots. Those belonging to the premolars were mostly fused, just like the ones that exist in other prehumans, early humans, and people alive today. The great apes characteristically have separate roots.[6]

Previously, prehumans had been recovered only from sub-Saharan Africa. But Graecopithecus not only shifts mankind’s origins to the Eastern Mediterranean but also moves back the split between chimps and people by several hundred thousand years.

The two fossils individually dated back to 7.24 and 7.175 million years ago. The most ancient African prehuman, Sahelanthropus, is between 6–7 million years old.

4 The Dmanisi Humans

Unearthed at the Dmanisi site in Georgia, Skull 5 is 1.8 million years old. Anthropologist David Lordkipanidze found the jawbone in 2000 and the cranium five years later.

The features include those of later and earlier humans. The face, teeth, and diminutive brain resemble earlier fossil humans. The braincase matched the more recent Homo erectus.

The debate continues over whether the Dmanisi remains are ancestral to Homo erectus or its own species, Homo georgicus, but Lordkipanidze and his team reached a more controversial conclusion.[7] After comparing it with five skulls found at Dmanisi over the decades, they believed that all belonged to one species that occupied the site at different times over millennia.

This, they claimed, was evidence for a single lineage going back to the first human, Homo habilis, 2.4 million years ago and then forward to Homo erectus. The study proposes that several earlier humans, conventionally distinct from Homo erectus, weren’t their own species but evolutionary changes.

Critics argue that such a major erasure of other species in favor of one cannot happen by just studying skulls while ignoring the body differences between the groups.

3 Lucy’s Mating Habits

Some of Lucy’s kind, Australopithecus afarensis, traveled in a group around 3.6 million years ago. They crossed modern-day Laetoli, Tanzania. When 14 of their footprints were found in 2015, it became the second set discovered at Laetoli.

Four decades earlier, 70 tracks galvanized the archaeological community because their extreme age proved that human evolution saw upright walking very early on. While the 1978 set was welcomed, a study about the new trail caused a rift.

Made by two individuals, one had a longer stride. Calculations placed him at over 168 centimeters (5’6″) tall, big for his kind. They crossed the same ash layer in the same direction as the other spoor.

The study suggested that both trails belonged to the same breeding group of one male (the tall guy) with females and young. Other researchers feel that five walkers of unknown age isn’t enough to determine gender.[8]

Even today, it’s hard to distinguish between footprints made by young women and teenage boys. Moreover, critics feel that it’s madness to identify a mating strategy for Australopithecus afarensis based on a few prints.

2 A Primitive Peer

A mystery began in 2013 when Homo naledi was identified for the first time. Several skeletons were found in the Rising Star Cave in South Africa. They possessed primitive traits and a brain that was two-thirds smaller than that of a modern human.

Yet the bodies appeared purposefully interred, hinting at intelligence and culture. From the ancient anatomy, researchers expected them to be 2–3 million years old. But testing returned a shocker: Homo naledi existed as early as 235,000 years ago.

This makes them a contemporary of different early Homo sapiens, the first true humans. Homo naledi, who had limbs suitable for tool use, walking, and climbing, reveals a diversity of human species never seen before in South Africa during the Pleistocene.[9]

Researchers don’t understand why interbreeding or competition didn’t occur between Homo naledi and other species since everyone shared a vast savanna and resources.

Homo naledi‘s origins hinge on two theories. They could be an earlier human that kept its primitive anatomy despite evolving alongside the branch that would later produce modern people. Secondly, they might have split from an advanced form, such as Homo erectus, and devolved in certain ways for some reason.

1 The Cerutti Mastodon

Mastodon bones in southern California could rewrite human history. In the 1990s, paleontologist Richard Cerutti excavated the Ice Age elephant bearing the fractures of forcefully broken bones. Nearby were damaged cobbles.

After fresh bones were cracked with similar stones and the same spiral fractures resulted, scientists concluded that it was an ancient attempt to extract the marrow. Uranium dating pointed at 130,000 years ago, provoking heavy professional criticism.

People conventionally arrived 15,000 years ago. The Cerutti theory makes that leap 100,000 years earlier. Opposing experts say there’s no evidence that humans butchered the creature. Also, bones hold uranium differently, which hampers accurate dating.

Elsewhere in the world, same-era humans were expert toolmakers. The site lacks any of the expected cutting equipment, and there’s no sign of people in the Americas until 115,000 years later.

If hominids somehow killed the mastodon, it upends everything known about how the Americas were settled, followed by a 100,000-year gap strangely lacking any human activity. Contradicting common belief, the first arrivals might not have been Homo sapiens. The dating adds Neanderthals and Denisovans as two more candidates.[10]

Read about more archaeological discoveries that shed light on our past on 10 Discoveries Of Lost Cultures That May Rewrite Our History and 10 Recent Archaeological Finds That Rewrite History.