Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Iconic French Things That Aren’t Entirely French

If someone were asked to make a sketch of the stereotypical Frenchman, the strokes of the pencil would undoubtedly outline someone sporting a mustache with a Gitane or Gauloise dangling from the corner of his mouth. The subject would be riding a bicycle with a baguette and maybe a croissant in a straw basket attached to the two-wheeler. There may be an accordion and a painting easel somewhere in the drawing and certainly a little French poodle at the Frenchie’s side.

But just how many of the features of our imaginary portrait are native to France, and how many were imported? As this list will illustrate, many things you may associate with France did not, in fact, originate there.

10 The Mustache

Not surprisingly, the mustache is an import. A cave painting, dated to 300 BC and portraying a Scythian warrior with a carefully groomed mustache, is often cited as the first evidence of the fashion. However, much older Egyptian artifacts—dating from as early as 2650 BC—show Clark Gable–like wisps gracing the upper lips of men painted on pottery and other vessels. The mustache had a good run of it in Egypt until 1800 BC, when the ruling pharaoh banned the sprouting of hair above the lips of his subjects.[1]

From that time on and up until the 20th century, facial hair became the target of many governmental decrees and laws. It is hard to track those specific to mustaches, however, since whiskers above the lip were often lumped in with those on the chin, if for no other reason than a lack of vocabulary. The Romans, for example, were certainly familiar with the existence of the mustache, but no Latin word for it existed.

In ancient Greece, on the other hand, where barbers were important members of society as early as the sixth century BC, three different words existed for the fuzzy upper lip, including mustax, which the Italians borrowed in the Middle Ages to come up with their own mustacchio. This word, in turn, was borrowed by the French, likely during the 15th century, when King Charles VIII was busy campaigning in Southern Italy.

Mustache cultivation, however, was important in France and all across Western Europe long before there were words to describe it. Throughout the Middle Ages, barbering was a serious undertaking. In addition to trimming hair, beards, and mustaches, barbers were performing other health care–related functions such as bloodletting and tooth extraction. To oversee the admittedly complex profession of the medieval barber, the first-ever barber’s guild was formed in France in 1076.

But similar guilds followed quickly in other countries, so what exactly makes the mustache so very French? Perhaps we owe that to foreign monarchs like Henry VIII and Peter the Great, both of whom levied taxes on beards, which made the mustache the king of fashion. Since every single ruling French monarch sported groomed facial hair, including a mustache, from Francois I (born in 1494) through Louis XIV (died in 1715), the French just knew how to wear the mustache better than anyone else.

9 The Baguette

This staple of the French diet may well be an import. It is difficult to prove, but there is enough evidence to cast doubt on the French origins of the iconic loaf. Of the three dominant theories on the birth of the baguette, the two claiming French origins seem flawed. The third, which attributes the baguette to Austrian bakers, is undoubtedly the most plausible.

The first legend holds that the baguette was a Napoleonic invention. Since the typical, round boule of bread was awkward for soldiers to fit into their packs and weighed between 3 and 6 kilograms (6.6–13.2 lb), Napoleon had the baguette invented. The problem with this theory is conservation. If you have ever left a baguette on your kitchen counter overnight, you know that it could not possibly last four days, which was the rations requirement for a soldier in the Grand Army.

A second legend suggests that the baguette was born with the Parisian metro. Construction workers who brought their heavy boule for lunch necessarily brought along knives to cut it. When disputes occurred and fights broke out in the dark tunnels under construction, violence could turn deadly. The stories reported may well be true, but they come too late to explain the origins of the baguette.

The baguette made its debut in Paris sometime between Napoleon’s Grand Army in the first part of the 19th century and the metro’s construction at the tail end of it, which is why theory number three makes sense.

In 1839, an Austrian, August Zang, opened a bakery in Paris called the Boulangerie Viennoise. He used a new method of steam-cooking bread using a lightweight flour with beer leavening and formed the dough into elongated ovals rather than rounds.[2] Zang’s bread likely took the shape that we know today in 1920, when a law was passed forbidding bakers to start work before 4:00 AM. In order to make sure their breads were ready for the breakfast rush, they made them thinner so that they would cook more quickly.

While France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, may not have been quite accurate when he said that the baguette “has been a part of humanity since its beginning,” we can hardly dispute his effort to protect the crunchy, flaky, doughy wonder by having it classified by UNESCO as a world treasure.

8 The Croissant

If the baguette does get protection as a world treasure, then so might its cousin, the croissant. Like the baguette, the origins of the croissant are nebulous, but most stories point back to Vienna and August Zang.

In 1683, Vienna was under attack by the Ottoman Empire. In the wee hours of the morning, as Ottoman warriors were preparing to sneak upon the city and destroy it, several bakers who had roused themselves from bed to prepare the day’s bread caught wind of the enemy’s presence and sounded the alarm, saving the city. As a reward for their heroic deed, Viennese bakers were granted the privilege of baking a special roll in the shape of a crescent, the symbol of the Ottoman Empire.

These kipferl had the vague appearance of a croissant, but the dough was very different. The pate feuillete that makes a croissant a croissant was not invented until the 17th century. So the “cakes in a crescent shape” that were served by the bishop of Paris at Catherine de Medici’s coronation ceremony in 1549 were decidedly not croissants.

What August Zang brought with him to Paris in 1838 was the dough and the method. In Vienna, Zang had been a young artillery officer in the Austrian army with a promising career and an even bigger ambition.[3] Some say that during a visit to the French capital, he was surprised by the lack of pastries. Others relate a visit by the French royal family to Vienna, during which one member commented on how well Viennese breads would be received in Paris. According to this story, Zang resigned from his army position the very next day, packed his bags, and left for the City of Lights, recipes in hand.

The French did not lose a second in adopting the croissant and making it their own. By 1840, at least a dozen bakeries selling Viennoiserie were thriving in the French capital.

7 The Bicycle

Just when the bicycle became the bicycle is open to debate. It is true that in 1861, Pierre Michaud had the brilliant idea of adding pedals to a two-wheeled, human-powered vehicle that had made its way to Paris, but that two-wheeled vehicle was the German Draisine.

The Drasienne or velocipede, as it was known in France, was designed by Karl Drais von Sauerbonn, a German inventor and forestry official, who apparently preferred inventing to overseeing the state of the forest paths. Making his rounds on the Draisine was much quicker than on foot and gave him more time to tinker in his laboratory.

Drais’s first human-powered, wheeled vehicle was called the laufmaschine (running machine). Appearing in 1814, it was heavy and cumbersome, boasting four large wooden wheels and a steering mechanism. In 1815, he simplified his invention, abandoning two of the wheels, making the other two out of iron, and adding a rope break.

To be fair, Comte Mede de Sirvac, a French nobleman, had invented the celerifere, a two-wheeled vehicle in the form of a horse, in 1791. But it had no steering, pedals, or brakes. According to Merriam-Webster, neither Mede de Sirvac’s nor Drais’s invention qualifies as a true bicycle, which it defines as follows: “a vehicle with two wheels tandem, handlebars for steering, a saddle seat, and pedals by which it is propelled.”

Even if pedals really are the deal-maker, though, the bicycle still isn’t French. Pedals first appeared on the dandy-horse or hobby-horse, as the vehicle was called in the United Kingdom, in 1839, when a Scotsman, Kilpatrick Macmillan, devised a system of levers, cranks, and pedals to propel the vehicle.[4]

6 The Cigarette

Just like its principle ingredient, tobacco, the cigarette is American, through and through. Native to South America, where it has been growing wildly for nearly 8,000 years, tobacco did not make its way to Europe until Columbus brought a few measly seeds and leaves back to Spain in the very late 15th century.

Tobacco use did not catch on immediately, though, and was not popularized in Europe until the mid-16th century, when Jean Nicot, French ambassador to Portugal, became convinced of the plant’s marvelous medicinal properties. He sent some to his queen, Catherine de Medici, along with a how-to for its proper use: dried, ground, and inhaled as snuff. This was a sure recipe to rid one’s self of a headache. Of course, once the headache was gone, the relieved patient was on his or her way to addiction to tobacco’s then-unknown ingredient, named in honor of Mr. Nicot.

Tobacco use in Mr. Nicot’s day was limited to snuff, pipe-smoking, and chewing. The first recorded use of rolled tobacco leaves dates to sometime in the second half of the first millennium in Guatemala. Shortly after 1492, when the explorer Rodrigo de Jerez tried taking rolled tobacco back to Spain, he was arrested: “The smoke billowing from his mouth and nose so frightened his neighbors he was imprisoned by the holy inquisitors for 7 years.”

At the same time in America, tobacco was booming to the point of being used as currency. The plant influenced the colonial economy in other ways, as well. The first crops grown for commercial purposes were planted in Virginia in 1612. Later, the first rolling machine was invented by an American, James Bonsack. The first sellers of prepackaged cigarettes? Also Americans. Allen and Ginter were also the first to export the tobacco sticks to Europe. By 1883, they had their sticks in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, and Switzerland, and they had a factory in London.

Another American, the first true king of cigarettes, was James Duke.[5] Already enjoying a monopoly west of the Atlantic with his American Tobacco Company, Duke formed an alliance with Britain’s Imperial Tobacco in 1902. Upon conclusion of the deal, he made a statement to the press: “Is it not a grand thing in every way that England and America should join hands in a vast enterprise rather than be in competition? Come along with me and together we will conquer the rest of the world.”

5 French Fries

That’s right, French fries—or freedom fries or whatever you might like to call them—are not French. They’re Belgian.

Native to Chile and Peru, the potato traveled to Europe by way of the Canary Islands. By the end of the 16th century, Spanish farmers there were exporting them to Europe, but they were viewed with great suspicion in France. At best, they were thought fit for animal feed. It wasn’t until 1772, when Antoine Parmentier, a respected army pharmacist, declared the potato fit for human consumption that the tuber stood even the slightest chance of one day becoming a fry in that country.

To the north, common people in Belgium living along the Meuse were accustomed to frying the small fish they caught in the river. They would slice them into strips and fry them up for snacks. In the winter, when the river froze and there was often no catch to fry, villagers in Namur, Dinant, and other river towns began slicing potatoes and frying them instead. By the late 17th century, the Belgian fry was a thing.

Thomas Jefferson, the US minister to France from 1784 to 1789, introduced the fry to America, but he did not call it the French fry. The fry only became French after World War I, when American soldiers stationed in Belgium brought it home with them. Since French is spoken in Belgium along the Meuse river, they called the fry French for the language, not the country.[6] And how do Belgians, who consume more of them than any other nation in the world, feel about French fries? “There’s no such thing as French fries.”

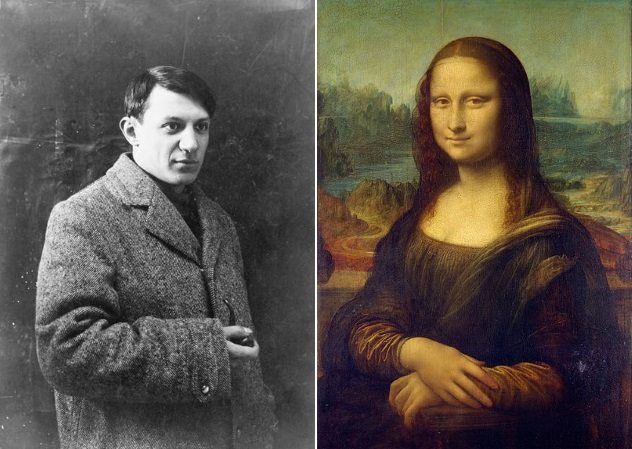

4 Picasso And The Mona Lisa

As artsy as the French are, they cannot (and do not) claim title to some of the most famous art that graces their capital. Paris’s Picasso museum may boast the largest collection of the artist’s work in the world, and more visitors may trek to the Louvre expressly to see the painting of Mona Lisa than any other artwork housed there, but neither Pablo nor Lisa is French.

Pablo Picasso was, of course, a Spaniard. Born in 1881, he settled in Paris in 1904. Although Picasso lived from then until his death in 1973 primarily in France, he never had French citizenship. But it wasn’t for want of trying. In 1940, with Germany set to invade France and Franco in power in Spain, Picasso’s situation as a resident alien had to have been uncomfortable. A self-affirmed atheist and devotee to the French communists, he would have had trouble fitting in to the artistic and cultural scene that Franco’s fascist government had established in his homeland. But in 1940, when Picasso requested French citizenship, he was turned down on the grounds of being an anarchist with communist tendencies.

Like Picasso, Leonardo da Vinci died on French soil as a foreign resident. But unlike Picasso, he was already an old man when he was invited to France by King Francois I in 1517. The subject of his most famous portrait, Mona Lisa (or “My Lady Lisa”), was every bit as Italian as the painter she sat for back in Florence in 1503. But that is where our knowledge of the model as a person ends.

Three main theories about her identity circulate, the oldest dating from 1550. It suggests that Lady Lisa is Lisa del Giocondo. This theory is widely accepted in France, where the painting is known as La Joconde. A later theory, proposed by Sigmund Freud and others in the 19th century, purports the model to be Leonardo’s mother, Caterina, and the painting to be a subconscious manifestation of the artist’s attachment to her memory and to his childhood. The third theory explains the resemblance of the artist to the model by theorizing that the Mona Lisa is actually a self-portrait of the artist, bequeathed as a puzzle to those who view her.[7]

In 2013, the Giocondo family tombs were excavated in the hope that DNA testing could settle the question once and for all. The exhumation, however, did not get us any closer to solving the mystery.

3 The Guillotine

By name, the guillotine is French, but by design, it is an import.

The Halifax Gibbet of Yorkshire, England, is believed to date back to 1066, around the time of the Normand Conquest. The first reference to it was recorded in 1280. The first recorded head severed by it, in 1286, belonged to John of Dalton. Local law stated, “If a felon be taken within the liberty of Halifax [ . . . ] either hand-habend, back-berand, or confessand, to the value of thirteen pence half-penny, he shall [ . . . ] be taken to the Gibbet and there have his head cut off from his body.

Other parts of Europe took care of criminals in similar ways. In 1307, Murcod Ballagh lost his head to a guillotine-like machine in Ireland. In Flanders and Germany, a device called the planke was used for beheadings throughout the Middle Ages.[8] During the Renaissance, the “Scottish Maiden” was notorious and claimed the lives of over 120 people. In 1702, Count Bozelli was hardly the only one to be separated from his head by the mannaia in Italy.

The guillotine was working overtime during the period of terror that followed the French Revolution, to be sure. It was also used extensively by the Nazis.

France’s relationship to the guillotine was nonetheless a curious one in the 1790s. Roughly 0.6-meter-tall (2 ft) replicas of the machine were sold as toys and provided children with hours of entertainment beheading dolls, rodents, and anything else that caught their fancy. Smaller working replicas were ironically fashionable for a time on the dinner tables of the well-to-do, where they were used to slice bread. “Victim balls” were also popular among aristocrats, but they were exclusive, and one had to be related to a victim of the guillotine to be invited.

2 The Accordion

Invented in Berlin by Friedrich Buschman in 1822, the accordion was first known as the Handaoline. In 1829, a Viennese musician, Cyrillus Damian, added buttons so that the left hand to play the chords while the right hand played the melody. He renamed the instrument the accordion, borrowing the French word for chord, accord. From Germany and Austria, the accordion migrated to Italy. Then, in the late 19th century, Italian immigrants brought it with them to France. The instrument was so enthusiastically adopted by the general population that accordion shops were set up in Paris before the turn of the century, the first one opening in 1890.

The accordion quickly became the musical centerpiece in cafes and cabarets.[9] It was perfectly adapted to the musette music of the popular balls that were held in the streets of Paris during the first decades of the 20th century. It was also perfectly adapted to the French national psyche. The accordion has been described as “instantly recognizable, with its minor keys that speak of an underlying sadness, coupled with jaunty melodies and playing styles that reveal the resilience of the human spirit.”

Perhaps no one did more to Frenchify the accordion than Edith Piaf. Born in Paris into a family of circus performers, Edith Gassion’s father was an acrobat, her mother was a singer and dancer, and her grandmother was a flea trainer. By the age of 14, she was performing on the streets of the capital and was soon fondly called Mome Piaf, or “little sparrow.” With an accordion in hand, she assumed the name and rose from rags to riches. The first French artist to conquer the American music market and France’s biggest international star during the first half of the 20th century, the melancholy and resilience of her music is echoed in her instrument of choice.

1 The French Poodle

Long regarded as the national dog of France, the poodle’s origins can officially be traced to Germany, where it is called the Pudel, from pudelin, meaning “to splash in water.” In France, the poodle is a caniche, which is a cross between the French word for “duck” (canard) and “dog” (chien). Known for its keen intelligence and its superior ability to learn, it is little wonder that the French took to it as much as it took to the French.

The poodle is stylish, too, but it wasn’t bred in France to be just another pretty face. As a purebred, the poodle was meant to work hard. Excellent swimmers with moisture-resistant coats, the poodle was (is) the ideal companion when hunting for duck or other fowl that might drop into water when shot.[10]

The standard poodle is represented in German art and referred to in German literature as early as the 15th century. Germany officially recorded its Pudel in 1750. In France, dogs resembling the poodle are carved into statues (at the 11th-century cathedral in Aix-en-Provence and the 13th-century cathedral in Amiens) and woven into tapestries (at the 16th-century Cluny Abby), but no official record of the caniche is found in France until 1885, when a male poodle named Milord entered the registers.

Allez, venez, Milord!

Melissa McCullough is a Stanford Ph.D. (French literature, 2000).

Read more about France and its history on Top 10 Fascinating Facts About France and Top 10 Dark Moments In The French Monarchy.