Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

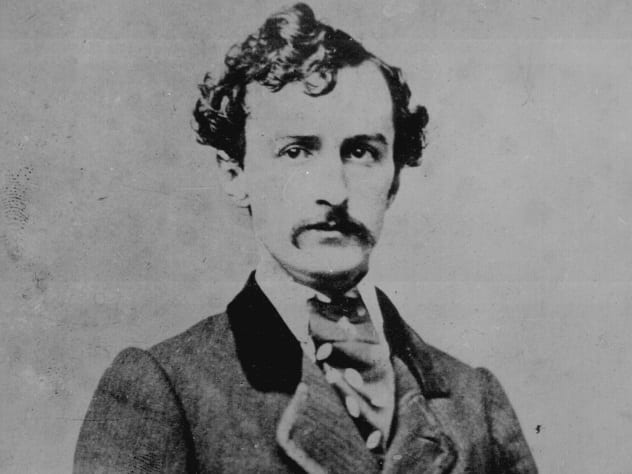

10 Intriguing Facts About The Manhunt For John Wilkes Booth

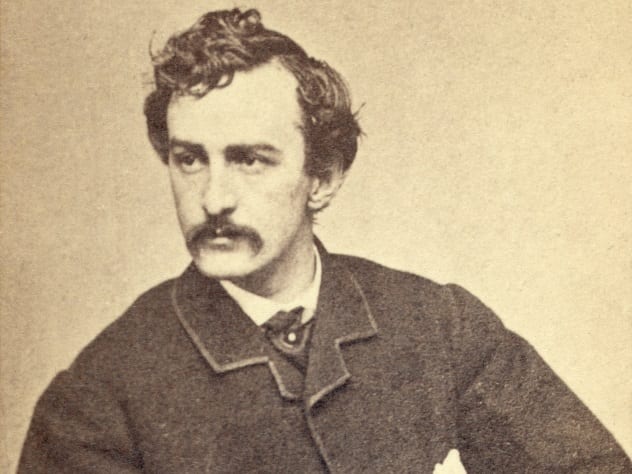

There are few names more notorious in US history than that of John Wilkes Booth. Booth, as most Americans know, is the assassin who shot and killed President Abraham Lincoln at the tail end of the American Civil War.

It occurred on the night of April 14, 1865, as Lincoln, his wife, and two guests were watching a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC. Booth snuck into group’s private box and shot Lincoln point-blank in the back of the head. Hours later, Lincoln died of the wound. Lincoln would be the first of four US presidents to be assassinated while in office.

While many Americans know that Booth killed Lincoln, few know about Booth’s daring escape from Ford’s Theater and the massive manhunt for the president’s killer that followed. Booth would be on the run for 12 days before eventually being brought to justice. Here are ten intriguing facts surrounding the manhunt for John Wilkes Booth.

10 Booth Attacked Three Other People That Night

Just seconds after Lincoln was shot, Major Henry Rathbone, who, along with his fiancee, was a guest of the president and the first lady that night, jumped to his feet and attempted to subdue Booth. However, he was unable to stop the assailant, who slashed and cut him with a dagger before jumping from the box to the stage of the theater.[1] Rathbone was left with a deep laceration on his left arm and later passed out from blood loss.

Rathbone would not be the last victim of Booth that night. After landing awkwardly on the theater stage and breaking his leg, Booth rushed to make his escape, at one point slashing and pushing William Withers Jr., the orchestra leader.

Once outside the theater, Booth made his way to his horse, which was being held for him by Joseph Burroughs, an employee of Ford’s Theater. Burroughs was unaware of what had just happened inside. As Booth mounted his steed, he struck the unsuspecting man with the butt of his knife and galloped away into the night.

9 The Manhunt Could Have Been Over Before It Started

After escaping Ford’s Theater, Booth made his way to the Navy Yard Bridge, where he hoped to cross into Maryland. However, the bridge was under curfew, and no one was to cross after 9:00 PM.

When Booth reached the bridge at around 10:30 PM, he was stopped and questioned by Union soldier Silas T. Cobb. Cobb asked Booth his name, and incredibly, Booth identified himself. News of Lincoln’s shooting had been transmitted via telegram to soldiers stationed around the city almost immediately, but Cobb hadn’t yet received the message.[2] After asking a few more questions, Cobb deemed Booth’s answers sufficient and allowed him to pass.

Five to ten minutes later, a second rider approached. Cobb stopped and questioned this man, who identified himself as “Smith.” Cobb allowed this man to cross as well. To his dismay, Cobb would later learn that this man was actually David Edgar Herold, an accomplice of Booth who had assisted in the attempted murder of Secretary of State William Seward earlier that night.

One is left to wonder what might have happened if the message of the attacks had reached Cobb in time. Would the conspirators have even made it out of Washington?

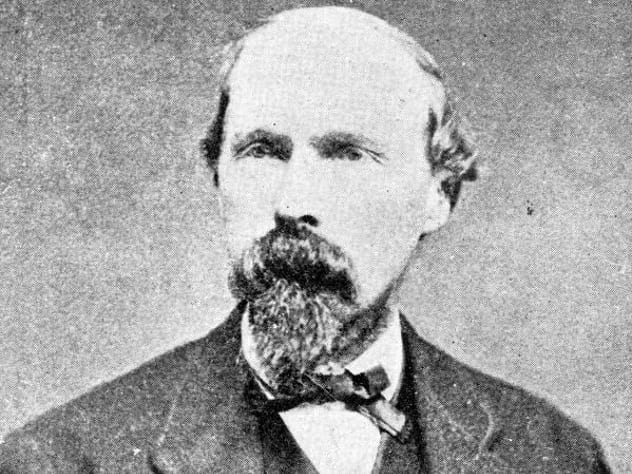

8 Controversy Surrounds The Role Of Dr. Mudd

After crossing into Maryland, Booth and Herold continued to make their way south. In the early morning hours of April 15, the two arrived and were welcomed into the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd. Mudd provided them with food and a place to sleep, and he treated Booth’s broken leg.[3] Upon their departure later that day, he also provided them with fresh horses.

In his trial, Mudd maintained that he did not know about the assassination or recognize Booth, despite having met him on at least two previous occasions.

Mudd was found guilty by a military tribunal and sentenced to life in prison for his role in assisting Booth’s escape. However, he was later pardoned by President Andrew Johnson after he helped contain an outbreak of yellow fever at the prison he was sent to. What exactly Mudd knew is still debated, and some in his family have continued to maintain his innocence.

7 Booth Was Shocked That The South Didn’t Support Him

As Booth continued to make his way south, doing his best to avoid detection, word of the assassination spread across the country. At one point, Booth got his hands on some newspapers and was stunned to realize that he was not universally praised by the South for his actions.

One Alabama paper, the Montgomery Daily Mail, denounced the assassination as a “dark and bloody deed.” The Raleigh Standard expressed its “profound grief” at the news.

“I am here in despair,” wrote Booth in his journal on April 21. “And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for, what made [William] Tell a hero. And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.”[4]

6 Even When Surrounded, Booth Refused To Be Taken Alive

On April 24, Booth and Herold reached Northern Virginia and stopped at the farm of Richard Garrett. Garrett, allegedly unaware of Lincoln’s assassination and under the impression that Booth was a wounded Confederate soldier named “James W. Boyd,” agreed to let the two stay in his barn.

Little did the fugitives know that this would be the end of the line for them. After receiving a tip about their whereabouts, a Union cavalry unit had raced to the farm, arriving at around 2:00 AM on the morning of April 26. After a brief interrogation, Garrett admitted that the two men were staying in his barn.

Booth and Herold heard the commotion and attempted to escape but quickly realized that they had been locked in by Garrett, who thought they might steal his horses. Within minutes, the barn was surrounded, and the fugitives were commanded to surrender peacefully.

Herold surrendered, but Booth refused and prepared to fight, exclaiming, “Well, my brave boys, prepare a stretcher for me!”[5]

5 Booth’s Last Words

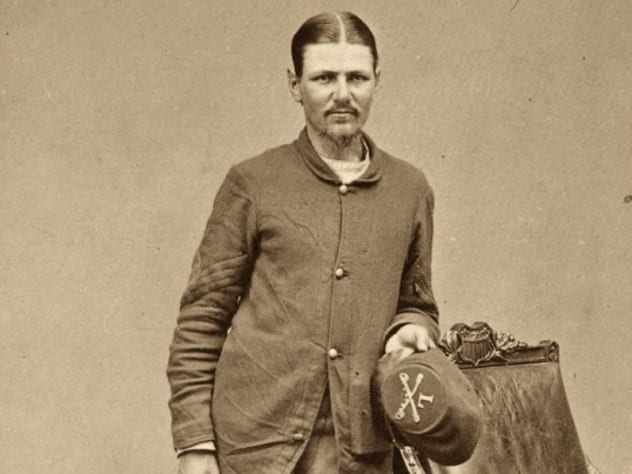

When Booth refused to surrender, the order was given to set the barn on fire in an attempt to drive him out. As the barn burned, one of the soldiers, a sergeant named Boston Corbett, saw through the cracks of the barn that Booth was raising his carbine rifle and beginning to take aim at the Union troops. Corbitt took aim with his revolver and shot, hitting Booth in the neck. Booth collapsed, and the soldiers rushed to the barn and pulled Booth out.

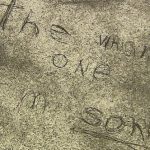

Booth was still alive, but just barely. The bullet had paralyzed him from the neck down, and he was bleeding profusely. Thinking he would die any minute, Booth whispered what he thought would be his last words, “Tell mother, I die for my country.”[6] But he lingered alive for several more hours. At one point, he asked for someone to lift his hands for him, and when he saw them, he spoke what would be his true last words: “Useless, useless.”

He died soon after.

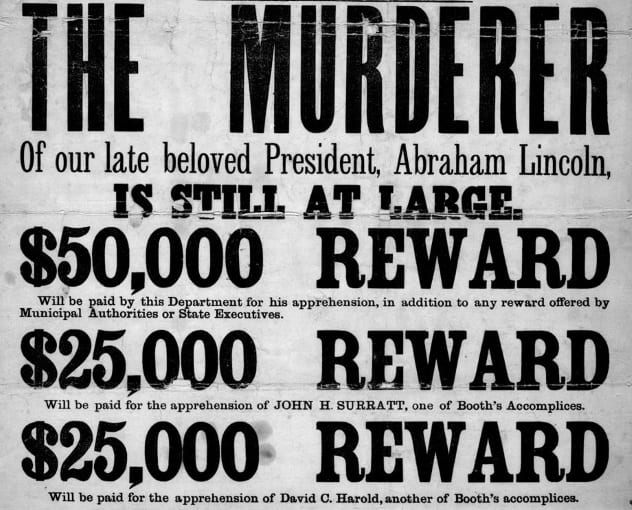

4 Dispute Over The Reward Money

With Booth dead and Herold captured, the minds of many of the men who participated in the operation undoubtedly turned to the substantial reward that had been offered for the capture of the fugitives. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had offered a mind-boggling $50,000 reward for the capture of Booth and $25,000 for Herold.[7]

It was ultimately up to Congress to decide who should get what percentage of the reward money. It was generally accepted at the time that the money should be allotted by rank.

Initially, it was believed that Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty, the man who was in command of the unit at the time of Booth’s capture, should receive the largest portion of the money. But the unit was also accompanied by two federal detectives, Everton Judson Conger and Luther Byron Baker, who played important roles in the operation. The group itself had also been originally dispatched to hunt Booth at the command of Lafaytte Baker, the head of the National Detective Police.

Conger and Byron Baker, at the direction of Lafaytte Baker, wrote to Congress, arguing that the operation was, in fact, a law enforcement action, not a military one, and as such, they should receive larger shares of the money. They contended that Doherty and his men were their subordinates and “though necessary, instruments” to their own work.

Upon hearing this, Doherty wrote his own letter to Secretary Stanton, calling the assertion a “fallacy.”

Congress eventually sided with the detectives and allotted $15,000 to Conger, $5,250 to Doherty, $5,000 to Byron Baker, and $3,750 to Lafaytte Baker. The rest was divided among other parties involved.

3 The Government Refused To Pay For Garrett’s Burned-Down Barn

In the wake of Booth’s capture, Richard Garrett petitioned the government to refund him for the burning of his of tobacco barn. Garrett alleged that he was unaware of who Booth was at the time and therefore not culpable in any crimes. He argued that the government owed him the then-astounding amount of $2,525 for the loss of the barn and the items inside.

Some of Garrett’s neighbors even testified to the man’s character, but the government would have none of it. They found it hard to believe that Garrett was not aware of who Booth was, and his claim was denied.[8]

2 Boston Corbett Went Crazy And Disappeared

After killing one of the most hated men of his time, Corbett enjoyed minor celebrity status. He even went on a publicity tour during which he told his tale to those who wanted to listen. But the good times were not meant to last.

Corbett was not a stable man. He was a religious fanatic so devoted to his Methodist religion that he castrated himself in order to avoid sin.[9] As his fame and reward money waned, his mental health deteriorated. He became convinced that friends of Booth were after him, wishing to do him harm. He was unable to hold down a job for very long.

In 1886, he was offered a job by a veteran’s group to become a doorkeeper at the Kansas State Legislature, which he accepted. However, this arrangement did not last long, either. One day, Corbett burst into the building waving his gun around. He was subsequently fired from the position and committed to an insane asylum. He eventually escaped from the asylum, but no one is exactly sure where he went or what happened to him after that.

1 Some Believe Booth Survived

As with nearly every traumatic, consequential event in American history, countless conspiracy theories have sprung up about what really happened to John Wilkes Booth. One of the more interesting theories suggests that Booth didn’t die that night in Virginia, but rather escaped and lived out the rest of his days under a false identity.

This theory, laid out in Finis L. Bates’s 1907 book Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth, claims that a lookalike was shot and killed that night, while the real Booth was nowhere near the scene. The book goes on to claim that Booth escaped to Texas, where he lived for many years under the pseudonym “John St. Helen.”[10] Bates alleges that St. Helen became gravely ill at one point and, thinking he was going to die, confessed to Bates that he was really John Wilkes Booth. St. Helen recovered, however, and soon after left town. Bates believed he committed suicide in Oklahoma in 1903.

Most historians have rejected the theory, but interestingly enough, the FBI was still investigating Booth and the assassination in 1977, more than a century after his alleged death.

Brad is a DC-based reporter and freelance writer. You can follow him on Twitter @bsylvester31.

Read about some less successful presidential assassins on 10 Bizarre Motivations of Would-Be Presidential Assassins and 10 Forgotten Attempted Assassinations Of US Presidents.