Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Shipwrecks That Are Still Unexplained

According to UNESCO, there are approximately three million shipwrecks scattered across the Earth’s surface.[1] The ocean is a vast place, and sea travel can be a hugely isolated and dangerous endeavor. Some ships are destroyed by storms, others run out of supplies or hit land, and some just outright vanish, never to be seen again.

For every shipwreck we understand, there are at least ten which are still shrouded in mystery. They are uniquely haunting places, catastrophes frozen in time and preserved hundreds or even thousands of feet below the surface. Here, we delve into some of the strangest shipwrecks that are still unexplained today.

10 The World Trade Center Ship

One of the greatest tragedies of the modern world happened on September, 11, 2001: Four commercial aircraft were hijacked by terrorists and flown toward key landmarks in the US. Two of these planes hit the 110-story World Trade Center towers, which collapsed later that day.

The disaster resulted in the total destruction of the World Trade Center, which had to be cleared of debris ahead of reconstruction plans. The ground was broken as part of a scheme to build an underground security and parking complex. But excavation had to be halted in 2010 when diggers encountered something very unusual 6.7 meters (22 ft) below ground level, slightly south of where the two towers had once stood: a shipwreck.[2]

Later analysis discovered that the trees used to build the ship were cut down in 1773, a few years before the Declaration of Independence. It was built from the same white oaks that also supplied builders with the materials they needed to construct Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence was signed. Archaeologists later found that the ship had almost certainly been built in Philadelphia, which was the center of the American shipbuilding industry at the time. As a result, the vessel was probably sailing during those key few years when America broke away from Britain.

Archaeologists still aren’t sure how the ship ended up there, but it is commonly understood that the area was still sea at the time of the American Revolution. The ship may have been scrapped and buried on purpose as part of a conscious attempt to extend the Manhattan coastline, or it could have just been another unfortunate victim of the fickle ocean.

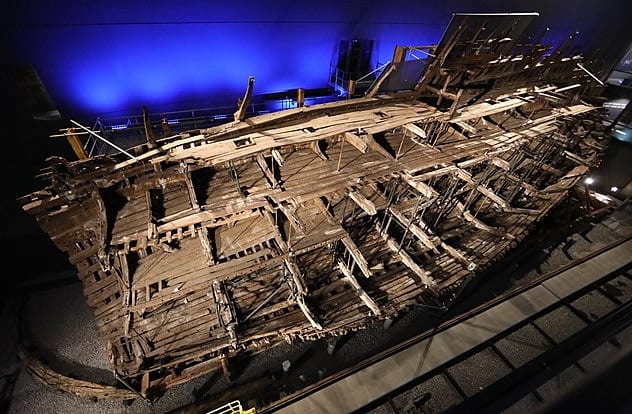

9 The Mary Rose

The Mary Rose was undisputedly the pride of the English navy for over 30 years. When it was first launched in 1511, the Age of Sail was only just beginning. It was the largest ship in the English fleet and one of the most advanced in the world: It took full advantage of the recent invention of the gunport and was one of the first ships in history capable of firing a broadside. It fought in numerous battles against England’s primary enemy at the time, France, before sinking in the midst of battle in 1545.

The circumstances of the Mary Rose’s demise still aren’t understood.[3] On the day of the battle, the English fleet was docked at Portsmouth harbor, making it especially vulnerable. The French galleys launched a surprise attack, and the Mary Rose and another warship sailed out to drive them off. According to a contemporary report, the Mary Rose suddenly leaned right, causing water to flood in through the open gunports. The ship sank quickly after that, taking over 90 percent of her 400-man crew down with it. It sank within full view of Southsea Castle: Today, a buoy marks the site, which can easily be seen from the castle walls.

A number of theories have been put forward to explain the tragedy, none of which are entirely satisfactory. One theory suggests the ship had been made too heavy by the most recent refit, which added more men and guns, but the refit was nine years before the sinking. A French captain present at the battle said it was sunk by a cannonball, but no evidence found at the wreck conclusively supports this. Another contemporary said that it was hit by a gust of wind while it was turning, and it had just fired its guns, which, added together, tipped the ship too far to the right. The Mary Rose has since been recovered from the seabed and is preserved in a museum in Portsmouth, but even now, analysts disagree over exactly what caused the sinking.

8 The Jenny Lind

In 1850, the Jenny Lind was more than 480 kilometers (300 mi) from the Australian mainland when it suddenly struck land. The ship had hit a small ridge which lay just below the water. The crew then survived for 37 days on a small, sandy quay while they built a new ship, before sailing over 600 kilometers (370 mi) to Moreton Bay on the Australian mainland. All 28 crew members survived.[4]

The feat was widely recorded in the newspapers at the time, and shortly after that, the surprise bit of land, known as Kenn Reefs, started appearing on navigation maps. After that, travel past the ridge—which lay right in the middle of a busy trade route—was much safer. But even today, we don’t know quite how many ships the ridge has actually claimed. The Bona Vista crashed into it in 1828, and a record made in 1857 states that the southern end of the reef was already “strewn with wrecks” even then. Modern estimates assume that at least eight ships have met their end on this deadly atoll.

The main problem is the incessant strength of the sea which batters the atoll. A trip to Kenn Reefs in the 1980s found that both the Jenny Lind and the Bona Vista were still half-visible above the water, but another trip in January 2017 found that they had since been destroyed. The tropical weather and powerful currents quickly reduce any ships that wreck there to their metallic parts, making it impossible to tell just how many have been claimed. The investigators are persistent, though: They’re currently in the process of cataloguing all the material still visible and checking contemporary shipping records in an effort to come up with an estimate.

7 The Waratah

The SS Waratah was an advanced passenger liner that was built in Glasgow. Intended to ferry people between the UK and Australia, it was expected to be a hardy and durable oceangoing vessel. However, it first raised concerns during its test voyages, when the captain complained that it sometimes felt top-heavy and struggled to maneuver.[5]

The ship remained in use. It departed Durban in July 1909, expected to take three days to reach Cape Town. The ship was sighted at sea over the course of the first day but then disappeared without a trace. One sailor who saw the ship go by thought it might have been giving off a lot of smoke, while another later reported seeing two bright flashes in the night. He was used to seeing them, however, since they were often caused by bushfires along the South African coast, and didn’t even think to record them in his log until he heard of the ship’s loss.

Since then, multiple efforts have been made to try to locate the ship. After nearly a century of searching, the South African National Underwater and Maritime Agency reported that they’d found it in July 1999, even performing a deep-sea dive to confirm it. Months later, however, they discovered that it was the wreck of a different ship—the military transport vessel Nailsea Meadow, which had a similar profile. To this day, no trace of the Waratah has ever been found. Its sinking led to the complete collapse of the Blue Anchor Line, which owned the ship, and they sold off their fleet the following year.

6 The Andrea Doria

The waters of the world emptied over the course of the World War II, as fewer and fewer people were willing to take the risk of traveling or vacationing in wartime. The end of the war brought with it a new golden age of cruise liners and luxury passenger ships. Bright and expensive, they crisscrossed the Atlantic in their droves, taking many people further than they’d ever traveled before. One of these vessels was the SS Andrea Doria. Its hull was split into 11 watertight compartments to prevent sinking, and it had completed 100 transatlantic journeys by the time it sank in 1956. Many people had considered it unsinkable, until it crashed straight into another ship, the Swedish vessel Stockholm.[6]

The circumstances of the crash are still unclear. Both vessels were failing to follow the conventional rules of sea travel: The Andrea Doria was sailing faster than normal through heavy fog in order to make it to New York by morning, while the Stockholm was traveling north of the usual eastbound route in order to shave time off its journey. Both captains saw the other ship on their radar but somehow failed to avoid a collision. Either one or both of them must have misread the data, and by the time they could see each other through the fog, it was too late.

Despite a desperate last-ditch effort to prevent a crash, the Stockholm plowed straight into the Andrea Doria’s flank with its icebreaker prow, penetrating 9 meters (30 ft) into the hull and killing dozens on impact. The Stockholm weathered the crash and remained seaworthy despite its mangled prow, but the Doria quickly began to sink. The collision threw it so far off balance that it couldn’t use its own lifeboats. What followed was one of the greatest maritime rescues in history, and most of the passengers were eventually saved. The Doria remains on the seabed today, and we’ll probably never know which of the two captains put her there.

5 The Zebrina

The loss of the Zebrina’s crew remains one of the strangest unexplained naval disasters of the 20th century. It was a three-masted sailing barge which was first put to sea in 1873. It sailed for decades without incident until September 1917, when it departed Falmouth in the UK with a shipment of coal, bound for the town of Saint-Brieuc in France.

Just two days after its departure, it was seen drifting just outside the port of Cherbourg, France. It was later found washed up on the coast south of the city. When the French coast guard boarded the vessel, they found it completely deserted despite it being in otherwise perfect condition: Even the table was neatly laid. The captain’s log had last been updated when the ship left Falmouth. Beyond that, there were no records.[7]

After an initial investigation, it was decided that a German U-boat attack was most likely. At the time, it was standard U-boat practice to board ships and take their crews captive or force them onto lifeboats before sinking the ship in order to prevent casualties. However, the crew never appeared on any German prisoner of war lists, and it was also standard practice for U-boats to sink their targets and to take their logbooks as proof of the sinking, both of which didn’t happen in this case. Because of the ongoing war, the French government didn’t pursue the investigation any further, and the ship was eventually broken up. The fate of the crew still remains a mystery.

4 The San Jose

The San Jose was a 64-gun galleon of the Spanish navy. First launched in 1698, it was used as a part of the annual Spanish treasure fleet. On its final voyage, it was serving as the flagship of the southern portion of the fleet, and its goal was to collect treasure along the coast between Colombia and Panama.

The fleet ran into trouble when it encountered a British naval squadron on June 8, 1708. The British fleet was victorious but failed to seize any meaningful treasure: Of the three ships they defeated, one was burned onshore by its crew, and another, the San Jose, exploded in the midst of battle. What caused the explosion is unclear, but it resulted in the deaths of all but 11 of its 600-man crew and the immediate loss of the ship. The rest of the Spanish fleet retreated to the safety of nearby Cartagena. The San Jose sank carrying more than $17 billion worth of treasure (in modern terms), a failure for which the British captains were eventually court-martialed when they returned home.

Any number of things could have caused the explosion, from a stray cannonball to a spark from a musket. We know for sure, however, that the San Jose is one of the most valuable wrecks in history, and it has long been referred to as the “Holy Grail of shipwrecks.” The site of the San Jose was a mystery until 2015, when it was discovered.[8] Colombia has stated its intention to recover the wreck and display the treasure in a museum: The ship’s exact location remains a state secret to ward off looters.

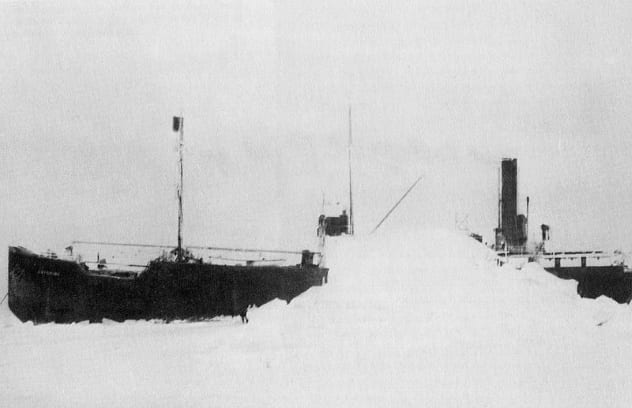

3 The Baychimo

The SS Baychimo had a very conventional history: Originally built in Sweden in 1914, it was owned by the German navy and sailed between Hamburg and Sweden until it was transferred to Britain as part of Germany’s war reparations. In 1921, it was acquired by the Hudson’s Bay Company and was frequently used to travel the northern reaches of Canada, collecting fur pelts to be transported back to Europe.

Ship crews operating so far north were used to dealing with ice, so when the Baychimo became stuck on October 1, 1931, they thought little of it. They abandoned the ship and took shelter in the town of Barrow and returned to their vessel when the ice had cleared.[9] The ship continued to get caught, however, and eventually, the company flew half the crew home. The other half, who were ready to wait out the winter if necessary, built a wooden shelter nearby. They were hit by a powerful blizzard on November 24, and when it cleared, there was no sign of their ship. The crew were ready to leave, but a week later, a local Inuit from Barrow told them he’d seen the ship drifting. They eventually located it, but it was so heavily damaged that they abandoned all hope of sailing it. They salvaged what cargo they could and left, expecting the ship to sink soon after.

But it didn’t. Instead, the ship continued to drift in the northern waters for years, eventually becoming a local legend. A whole host of stories have appeared over the years, some claiming that it became stuck in a glacier. The last credible sighting, however, dates to 1962, more than three decades after it was abandoned. It was allegedly seen drifting along the Alaskan coast by a group of Inupiat, who were traveling in kayaks. Despite several searches, not a single trace of the ship has ever been discovered.

2 The Patriot

The Patriot was a nimble schooner which saw action in the War of 1812. Before it was drafted for naval service, the Patriot had been a pilot boat, so it was very fast. This made it a good privateer, and it was employed to successfully raid and harass British shipping. By December 30, however, it had been repurposed and was refitted as a civilian ship. It departed Charleston after months of successful operations, intending to dock in New York. On board was Theodosia Burr Alston (pictured above), daughter of Aaron Burr and wife of the governor of South Carolina.

Despite painting over the ship’s name and carrying an authoritative letter, the crew were met by a British patrol, who stopped the ship on January 2, 1813. The ship’s guns were stowed just below the deck, and the hold was full of booty gleaned from months of privateering, but the patrol eventually allowed it to continue.[10]

Soon after that, however, it must have disappeared, because the ship never arrived in New York. There were immediate speculations about its fate. Many believed the ship must have been captured by pirates, since dozens of them prowled the North Carolina coastline. Several newspapers reported “deathbed confessions” from pirates and others over the next few decades, each of whom claimed to have been involved in capturing the ship. One man even claimed he’d helped to lure the ship ashore, where he and his companions looted it and killed the crew.

The most likely scenario, though, is that it sank during a storm: According to the log of a blockading British fleet, a severe storm struck on the night of January 2, which continued into the next day. Experts predict that the area where the storm was most fierce was where the Patriot likely was at the time. The case, however, remains uncertain.

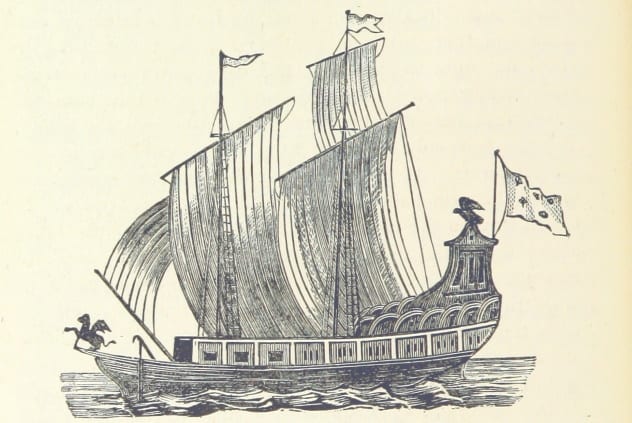

1 Le Griffon

Thousands of ships have sunk in the Great Lakes over the centuries, but the very first one of note, Le Griffon, still eludes explorers even today. It has become the target of many famous searches, each one fruitless. Many today joke that it is the most found ship in North America, but its fate remains a mystery even today.

It was built in 1679 by Rene Robert Cavalier (better known as La Salle) at Cayuga Creek, as part of his expedition to discover the Northwest Passage. At the time, the French suspected that the Great Lakes fed into the Pacific. La Salle and his crew of 32 departed on the ship’s maiden voyage on August 7, planning to map the Great Lakes. He and many of his crew disembarked on an island on September 18. The ship was sent with six crew back to Niagara, but it disappeared along the way.[11]

There have been many theories to explain the ship’s disappearance, from a Native American attack to a vicious storm. Over time, dark rumors surfaced among the native tribes that La Salle met: sightings of men who looked a lot like the missing crew members, wearing pelts which sounded like the ones that had gone missing. La Salle himself was convinced that the crew sank the boat on purpose and seized the cargo for themselves, but he was never able to prove it.

Today, finding the ship is a lifelong quest: Several explorers have dedicated decades of their lives to finding Le Griffon and have investigated dozens of potential claims, all achieving nothing. The rabid, sustained public interest has led to a torrent of myths, legends, and half-truths that have only gotten in the way of uncovering Le Griffon’s real fate.

Read about more amazing shipwrecks on 10 Shipwrecks Frozen In Time and Top 10 Catastrophic Shipwrecks.