History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

10 American Inventions That Aren’t American

With the largest GDP in the world, it’s not hard to imagine most of the inventions of the modern day coming from the United States. Any system based on capitalism and free enterprise is bound to drive innovation, even if the motives for that innovation aren’t exactly sparkling white. But the truth is, some of the most common things we use today were invented outside the borders of the ol’ Stars and Stripes, even if they went on to live a fruitful life in the hands of American consumers—saturating the market to the point that it’s hard (for an American at least) to imagine them coming from anywhere else. Here are 10 “American” inventions that were invented neither in America nor by an American.

SEE ALSO: 10 Accidental Inventions That Changed The World

The battery is a staple of modern life. They’ve changed a lot over the years, but the core principle is still the same—and it’s probably about 100 years older than you’d think. Most of the electrical pioneering in the world was happening in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Thomas Edison, Nicola Tesla, Heinrich Hertz—these and other great minds were filing hundreds of electrical patents that shaped the 20th century into what we know today.

So it might come as a surprise to learn that the battery was invented a century before any of this—in 1800, by Alessandro Volta (an Italian). His “battery” was called the Voltaic Pile and combined layers of copper, zinc, and cardboard soaked in saltwater. The design was modeled the work of another Italian, who noticed that a dead frog’s legs will twitch if an electrical charge touches them. Volta simple replaced the frog legs with salt water to create a circuit.

As a matter of fact, nearly every stage in the evolution of the battery has come from a different country. An Englishman improved on Volta’s battery, a Frenchman developed the first rechargeable battery, and a Swede invented the nickel-cadmium battery, which we still use today. Really, the only American influence came from Benjamin Franklin, who was the first person to use the word “battery.”

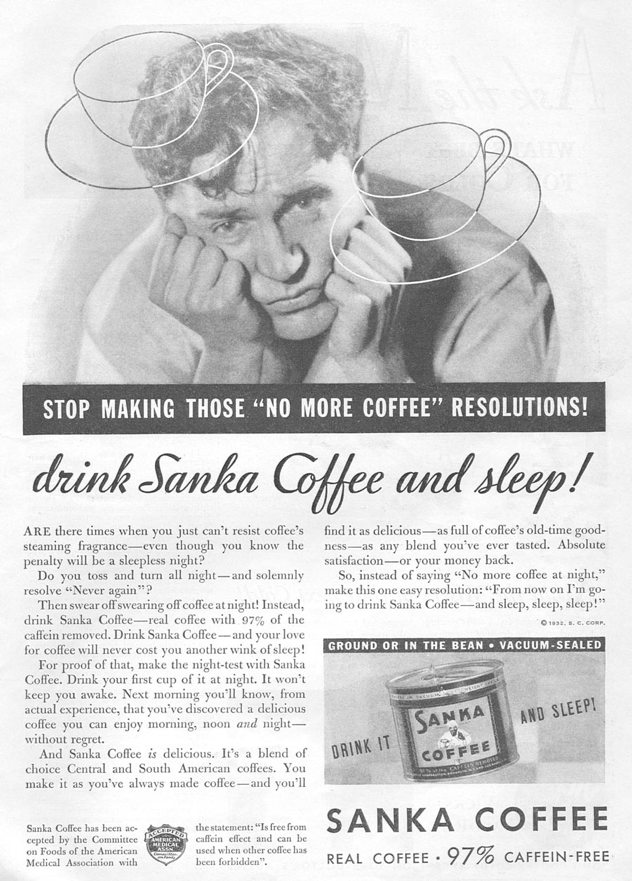

As everyone knows, coffee beans naturally have caffeine. That’s why most people drink it. But millions of “health conscious” Americans reach for decaf over the caffeinated brew. Easy enough, since it’s available in every coffee shop and every office across the country. It’s as American as apple pie.

Except, of course, that it’s not American at all (incidentally, neither is apple pie). The process of decaffeination was invented by a German named Ludwig Roselius in 1903. It was later widely marketed in the U.S. under the brand name Sanka. In addition to caffeine, coffee also has more than 400 other chemicals, all of which add their own personality to the overall taste, texture, and smell. So removing one specific chemical while keeping everything else intact isn’t the easiest thing in the world. Roselius’s process involved steaming the coffee beans with acid and then soaking them in benzene, which pulled out the caffeine. Since benzene has an annoying tendency to cause bone marrow cancer, modern decaffeination is slightly different.

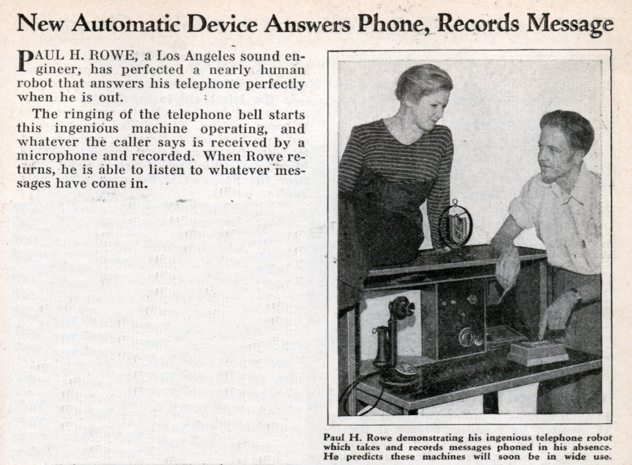

Once the telephone was invented, it didn’t take long for someone to invent a way to screen calls from unwanted callers. Thus, the answering machine was born. For the most part, the answering machine is credited to Benjamin Thornton, an American inventor who filed his patent in 1936. However, just a year earlier a man named Willy Mueller patented an answering machine in Switzerland. Yet this article from the 1930 issue of Popular Mechanics describes a new device as “a robot that answers the phone for you,” five years before Mueller. In all honesty, the history of the answering machine is as confusing as a caterpillar orgy, but one thing is for sure—it was not invented in America.

That’s because it was a Danish inventor named Valdemar Poulsen who built the first device that was able to record a message and play it back later, all the way back in 1898. It was just too bulky and cumbersome to be practical. As far as modern machines go, it wasn’t until 1960 that answering machines were even sold in America—the Ansafone, brainchild of Japanese inventor Kazuo Hashimoto and the first digital answering machine in the world.

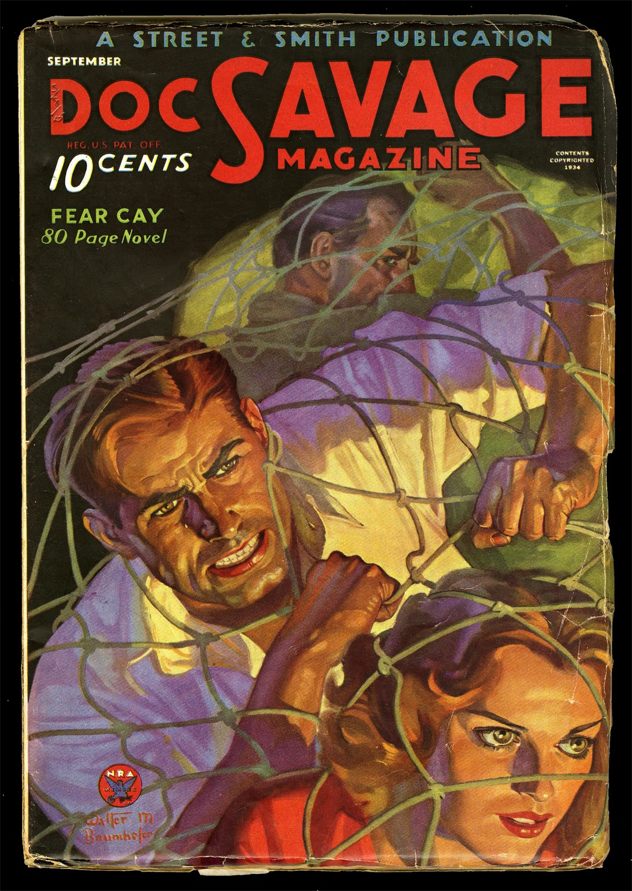

The notepad is one of those things that’s so common we just take it for granted. But this one tiny innovation ended up setting the standard for nearly a century of paper binding. The same process was later used to bind books, especially the American pulp fiction novels of the 30’s and 40’s that brought commercial reading to the mainstream.

Before the 1900’s, most paper was just stacked in a pile and kept that way. But in 1902, Australian J.A. Birchall decided to put a thin strip of glue across the top of a stack of paper and slap a sheet of cardboard on the back. And just like that, the notepad was born. They were originally sold as Silvercity Writing Tablets, and went on to become one of the most popular products in the world.

Thirty-eight million Americans wear contact lenses instead of eyeglasses every day. By all accounts, eyeglasses have been around since 13th century Italy, and the design of these haven’t changed much over the years, except of course for different types of frames, which change according to whatever fashion is current. However, it took over five hundred years before, in 1887, a German named Adolf Fick made the decision to do away with frames altogether and simply stick the lens right in his eye.

The first contact lenses were huge—21mm (0.8 inches) wide and made from blown glass, with a sugar solution between the lens and the eye to cut down on friction. They were bulky and uncomfortable, but blown glass contacts stuck around for 50 years until they were replaced with plastic ones in 1936.

Even though Adolf Fick was the first person to make a practical (well, semi-practical) contact lens, he certainly wasn’t the first to try. Leonardo da Vinci is said to have invented a type of contact lens in 1508 made out of a bowl of water. Similarly, Rene Descartes supposedly built a water-filled tube that was designed to go into the eye, but the idea never took off because it stuck out so far you couldn’t blink.

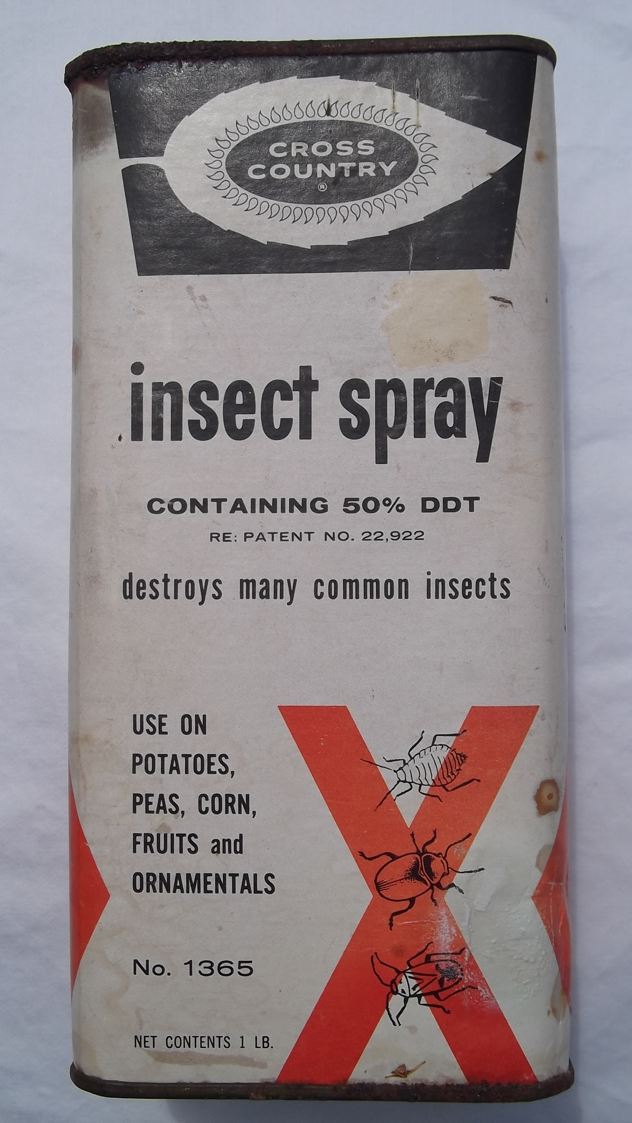

When you think of pesticides, you probably picture something like DDT. Currently banned in 170 countries, DDT was for a time one of the most common pesticides in the U.S., with thousands of farms using tens of thousands of pounds of the chemical to spray their crops. DDT was especially common during WWII, when Allied soldiers used it to fight off typhus. Out in the South Pacific, the army was literally spraying DDT into the air around their soldiers to keep mosquitoes (and malaria) at bay.

But it wasn’t invented in the same country that brought it to such global prominence. That honor goes to Othmar Zeidler, a German chemist who first synthesized dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (that’s DDT) in 1874. Even so, it wasn’t until another chemist in Switzerland named Paul Hermann Muller discovered that it could be used to kill insects in 1939 that it experienced its infamous boom. For his discovery, Muller was awarded the Nobel Prize.

Compact discs, or CDs, were one of the defining technologies of the 1990’s and 2000’s. They successfully killed cassette tapes, and they’re probably the last physical audio technology that we’ll ever have, now that mp3’s and digital formats pretty much dominate the music industry. But CD’s had a longer lifespan than most people might realize. When do you think were they invented? Early 90’s? Late 80’s? It was actually 1974, nearly a decade before they even became available to the public market.

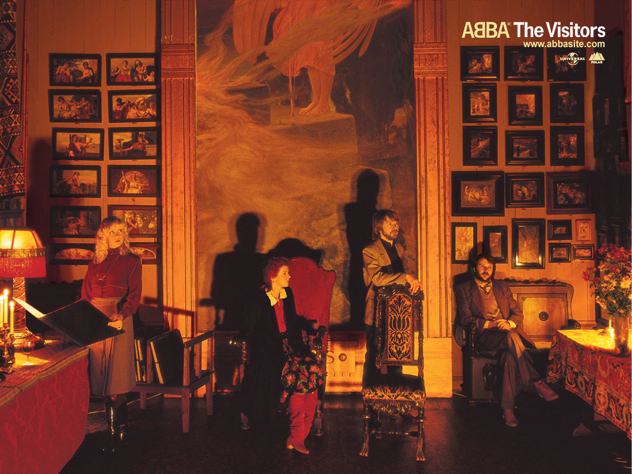

And the inventors were none other than the Dutch company Philips and the Japanese company Sony, which actually isn’t surprising at all. In the mid 70’s, both companies independently began working on technologies that could imprint digital sound onto a small plastic disc. In a move rarely seen among industrial giants, the two companies decided to join forces to develop the technology as fast as possible. The first album ever recorded on CD was ABBA’s The Visitors in 1981.

If America can’t claim decaf, DDT, and contact lenses, at least we have the TV going for us, the most American invention of all time. Well, wrong again. TV is actually a Russian invention. Specifically, it was a Russian engineer named Boris Rosing who, in 1907, used a cathode ray tube to receive images, creating the earliest framework for transmitting light and pictures to a receiving screen.

The invention was born, but like most technologies it took a few years and several participants to make it happen. In 1925, a Scottish scientist named John Logie Baird transmitted moving images to a cathode ray tube with a 30 line resolution (lines, not pixels). And back to Russia, a Leon Theremin boosted the quality of early TV’s up to 100 interlocking lines, bringing us closer to what we have today. At least, what we had before LCD screens. You can bet that very few Americans at the height of Commie hate during the Cold War realized they were getting their news from a Russian technology.

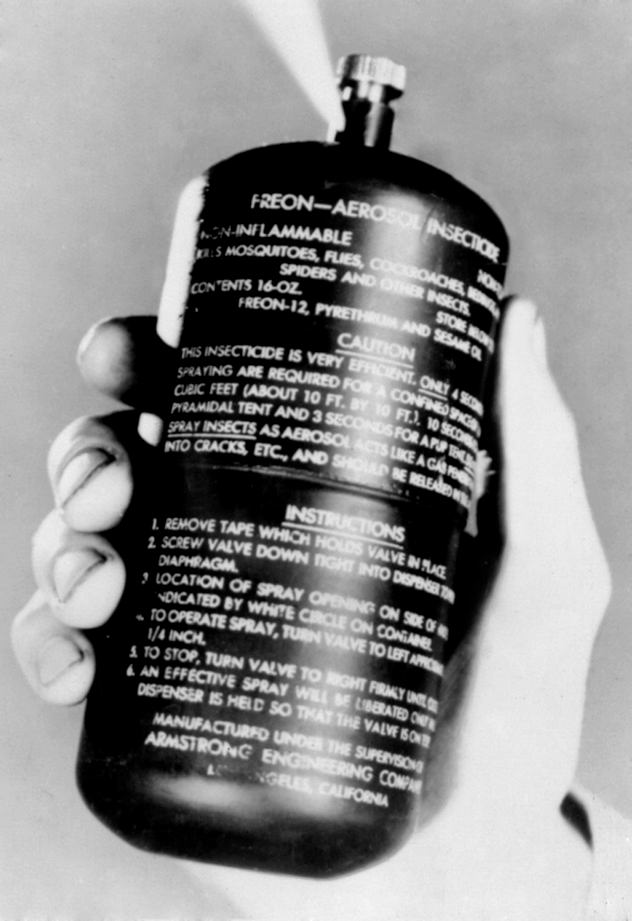

Aerosol spray cans are fairly common all over the world, but the first ones were sold in the U.S. in 1931. Since then, the core idea has remained relatively unchanged—a payload and a propellant are contained in an airtight metal can, and they’re released by pushing a button at the top of the can. Buy any can of spray paint right now and it wouldn’t be terribly different from what was being used in the 30’s.

If they were introduced to the world in America, then it makes sense that they were invented by an American company. In reality, an American company bought the patent for 100,000 kroner from a Norwegian scientist named Erik Rotheim, who had patented his aerosol invention in Oslo, Norway five years earlier.

Ask any Canadian where the telephone was invented, and they’ll proudly point right down at the permafrost under their feet. Ask an American, and you’ll get the same answer—a finger pointed straight down at American soil. Despite the fact that Alexander Graham Bell filed the patent for the first electric telephone in the U.S. Patent Office in 1876, his work in the early 1870’s took place mostly at his family home in Brantford, Ontario. That’s where he and his assistant, Thomas Watson, first transmitted an audio tone over a wire by plucking a metal reed, like a harp. This was the first time a sound had ever been sent from one place to another electronically—the framework of the telephone was born.

However, Bell had already promised his investors that he would register his device as an American invention, so the patent was filed in the U.S., and thus America got to claim the telephone as its own, even though the invention itself took shape on Canadian soil. If you’re interested, you can read Bell’s entire lab notebook online.