Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Ways Leprosy Was Nothing Like You Thought

The ringing of bells by the social outcast, the rotting flesh, the leper colonies where people were sent to die . . . the ancient disease leprosy has some very specific images associated with it. A lot of that is inaccurate, though—like so much from history, it’s far more complicated than we’re typically taught.

SEE ALSO: Top 10 Fascinating Diseases That You Can Smell

10It Still Exists—In Huge Numbers

We usually think of leprosy in the context of the Middle Ages or a biblical plague. Leprosy is still around, however, and an estimated two to three million people suffer from leprosy even today.

An exact number is impossible to document, as most of the people who contract leprosy are in poor, underdeveloped areas. An estimated one million cases of leprosy affect people in India today, and the number of reported cases are growing in some areas. The World Health Organization reports that some parts of India officially eliminated leprosy in 2005, but many such districts report a drastic resurgence since then. Between 2010 and 2011, doctors noted more than 125,000 new cases.

And it’s not just happening in remote areas of India. In the southern United States, 213 new cases of leprosy were reported in 2009, with about 6,500 cases in the whole country.

9The Bells Originally Attracted People

One of the most vivid associations people have with lepers is the ringing of bells, warning people to stay clear of the approaching threat. That wasn’t the original reason behind the bells, though; originally, lepers weren’t viewed with this fear.

Up until the 14th century, lepers relied on the kindness of strangers. Many lost their voices because of the disease, and the ringing attracted people’s attention so they would give the afflicted a donation. These donations were often the only way lepers could survive, but some towns banned the ringing because of the racket it caused.

8Lepers Initially Weren’t Shunned At All

Modern archaeological research has discovered that our view of the medieval leper has been very wrong, up until a certain point in history.

Between 1000 and 1500, the European definition of leprosy covered pretty much all skin conditions. Excavations of leper hospitals in France and England have uncovered not only what we now call leprosy (or Hansen’s disease), but also malnutrition and tuberculosis. Though these hospitals were usually on the outskirts of the medieval town, this was a simple consequence of land availability rather than any conscious effort to ostracize the patients.

The quality of early leper hospitals suggests the patients received high-quality care. Most appear well built and were expanded and renovated as needed. They included not just dormitories but chapels as well, and the graveyards where patients were buried were carefully dug, marked with individual stones, and often contained religious iconography.

Only with the coming of the plague were the visibly sick avoided rather than helped.

7Religion Spread It, Plague Almost Stopped It

Attempts to trace the spread of leprosy have uncovered some bizarre details. Comparison of the pathology of the different strains of leprosy have revealed that the type prevalent in the Middle East today struck Europe 1,000 years ago. Since 11 varieties of leprosy currently exist, researchers can use the types to trace just how the disease spread.

It spread most rampantly during the Crusades. A quarter of the European population then suffered from leprosy, helped by the introduction of new illnesses to which formerly isolated populations had no resistance.

And if religion spread leprosy, the plague nearly stopped it. When the Black Death ravaged Europe, it coincided with a dramatic drop in the cases of leprosy. One theory suggests that we were starting to build up an immunity to the disease (now, about 95 percent of the population is immune to it). Another theory says the plague killed whoever would have been most susceptible to leprosy otherwise—the poor, the malnourished, and those with compromised immune systems.

6Royal Care

Not all Middle Age lepers were doomed, and some monarchs went out of their way to provide for them. Queen Matilda of Scotland, well known for her charitable acts, made a special point to extend her grace to the lepers among her subjects. She even went as far as inviting them into her personal chambers and publicly touching their open sores to dispel people’s fears.

Matilda followed in the footsteps of her mother Margaret, who would be canonized in 1250 for her charitable works. Along with her father Malcolm, Matilda washed the feet of the poor every day during Lent. She also founded St. Giles, a hospital dedicated to the lifelong care of lepers. She gave money to other, similar institutions, like a hospital in Chichester and a women’s facility in Westminster.

England’s King John also set laws to benefit lepers. He established the hugely successful Stourbridge Fair in Cambridge specifically to help them earn extra income.

5Transmitted By Armadillos

Most diseases stay within a single species; others, like rabies and the flu, jump between animals and humans. Leprosy was long thought to hit humans exclusively, but recently, we’ve learned that armadillos can also harbor the leprosy virus.

Some 20 percent of wild armadillos carry leprosy. In the southern US, armadillos are hunted for their meat, and ingesting the meat can mean ingesting leprosy as well. Symptoms are usually misdiagnosed, since leprosy is so rare in the region. Cases that might otherwise be treated progress irreversibly.

But it’s not all bad news. The virus can’t survive without a host, so it’s long been difficult to study. Samples in laboratories die within days. Now, however, researchers can study the effects of the disease in a non-human host.

4Flesh Doesn’t Rot

A leper’s flesh doesn’t rot and fall off in pieces like you might picture. The image probably comes from one of the actual symptoms—the sores. But these trademark skin lesions can be very faint, more along the lines of a slight discoloration rather than the putrid flesh we typically imagine. Skin can also develop thick patches or abnormal growths, numbing large areas.

These numb areas, along with enlarged nerves, remove sensation, leading to a host of other problems. We rely on sensation—specifically pain—to tell us when we’re hurting ourselves. That might seem like a basic concept, but those with no feeling can suffer from cuts and burns before they even realize anything’s wrong. Injuries that would be mild with warning signs can become severe.

Untreated, numbness turns to permanent paralysis. Since leprosy matures slowly within the body, symptoms might take as long as 10 years to develop after infection, making diagnosis difficult.

3Biblical Leprosy Wasn’t Leprosy

Part of the reason lepers became so shunned in the later part of the Middle Ages was because of the biblical stigma attached to them. But a closer look at the description of leprosy in the Bible shows that it talks about something completely different from modern leprosy, otherwise known as Hansen’s disease.

In the Bible, leprosy is also known as sara’at, and it’s described as a skin infection. While that might seem in line with the basics of modern leprosy, biblical leprosy could be anything from a rash or a red patch of skin to swollen spots. Priests diagnosed it, and—in sharp contrast to modern leprosy—it was said to be highly contagious.

Archaeological excavation from biblical times shows no signs of the modern disease, and many trademark signs of modern leprosy, such as deformity or loss of feeling, aren’t mentioned in biblical texts.

Perhaps most significantly, the Bible describes leprosy striking inanimate objects. Mildew on a person’s house, possessions, or clothes was thought to be a sign that they were unclean and unholy. A priest would examine the home and declare whether or not the “leprosy” was the work of an angry God. If it was, the house would be quarantined and cleaned; if the mildew and mold persisted, it would be destroyed.

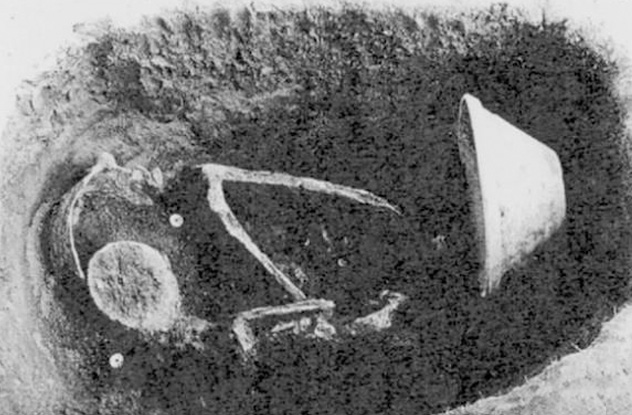

2Preventative Burials

Leprosy reached well into Asia and into the Americas, in addition to Europe. People across the globe shared many European concerns over leprosy, which might explain a bizarre burial method in Japan.

Nabe-kaburi involved people being buried with pots over their heads. The 105 Nabe-kaburi burials that have been excavated include both men and women spanning a variety of ages. The pots could be iron, earthenware, or mortar covering. The earliest remains date to the 15th century, and the latest are from the 19th.

According to Japanese folklore, a pot on a person’s head stops the disease that killed them from spreading. We’ve long considered that the buried pots tied in to this, but until recent advances, it’s all been speculation. Now, however, we’ve confirmed that many Nabe-kaburi individuals suffered from leprosy.

1The Leper Knights

Lepers might have a reputation as being ostracized by the population as a whole and by Christians specifically, but the Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem grew out of leprosy and welcomed leper knights.

After the capture of Jerusalem at the end of the First Crusade in 1099, invading European knights took over a leper hospital. The first hospital master was known as Blessed Gerard, and within a few decades, the hospital was receiving funding from the Order of Malta. As we discussed, leprosy grew most strongly during the Crusades. So many leprous knights came to the hospital that the organization evolved into a military one.

Knights who contracted the disfiguring disease joined the Order of Saint Lazarus, with the Templars paying them a stipend to do so. A handful traveled back first to France and then to England as ambassadors, establishing branches of the order back home in Europe. The original buildings in Jerusalem expanded to include a convent that fed and sheltered wives of the leper knights, several chapels, a mill, and several more hospitals. Saladin’s invasion ended the expansion, but the Papacy continued to protect the organization. When most of the order died, the remainder recruited non-lepers.

The Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem still exists today. Branches all over the world strive to serve their faith with the same humility and devotion that the leper knights first showed centuries ago.

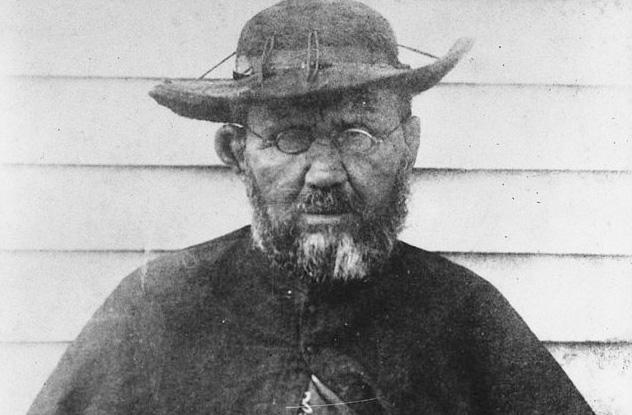

+The Leper Saints

When leprosy came to Hawaii in the 1800s, sufferers were rounded up and taken to the island of Moloka’i. Belgian immigrant Joseph De Veuster volunteered to care for the more than 700 people isolated there. Though not the first person to take up the cause, he had the largest impact on his Hawaiian charges.

More than a caretaker, the renamed Father Damien provided not just medical care but personal interest, support, and social interaction in the native language, as well as organizing running water systems, building schools, and raising awareness in the government. After 12 years living among the lepers, he was diagnosed with leprosy. He died in 1889, at 49 years old.

At his bedside was Mother Marianne, another devotee who had dedicated her life to serving the leper community of Hawaii. Mother Marianne was a Franciscan Sister who came to the island in 1883 at the age of 45. She died in 1918, aged 80.

Father Damien was raised to sainthood by Pope Benedict XVI on October 11, 2009, and Mother Marianne was canonized in October 2012, both recognized for their selfless devotion to the most shunned of humans.